Every Passover, my aunt swept into our San Fernando Valley home with wrists full of turquoise, a bob of frizzy straightened hair, and a teakwood bowl of bland Ashkenazy food. She was a socialist Jew raised in Miami. She went to the Peace Corps, lived in Greenwich Village during the Sixties, and followed up with a stint in Santa Fe, before heading to a rent-controlled Santa Monica apartment in the Eighties.

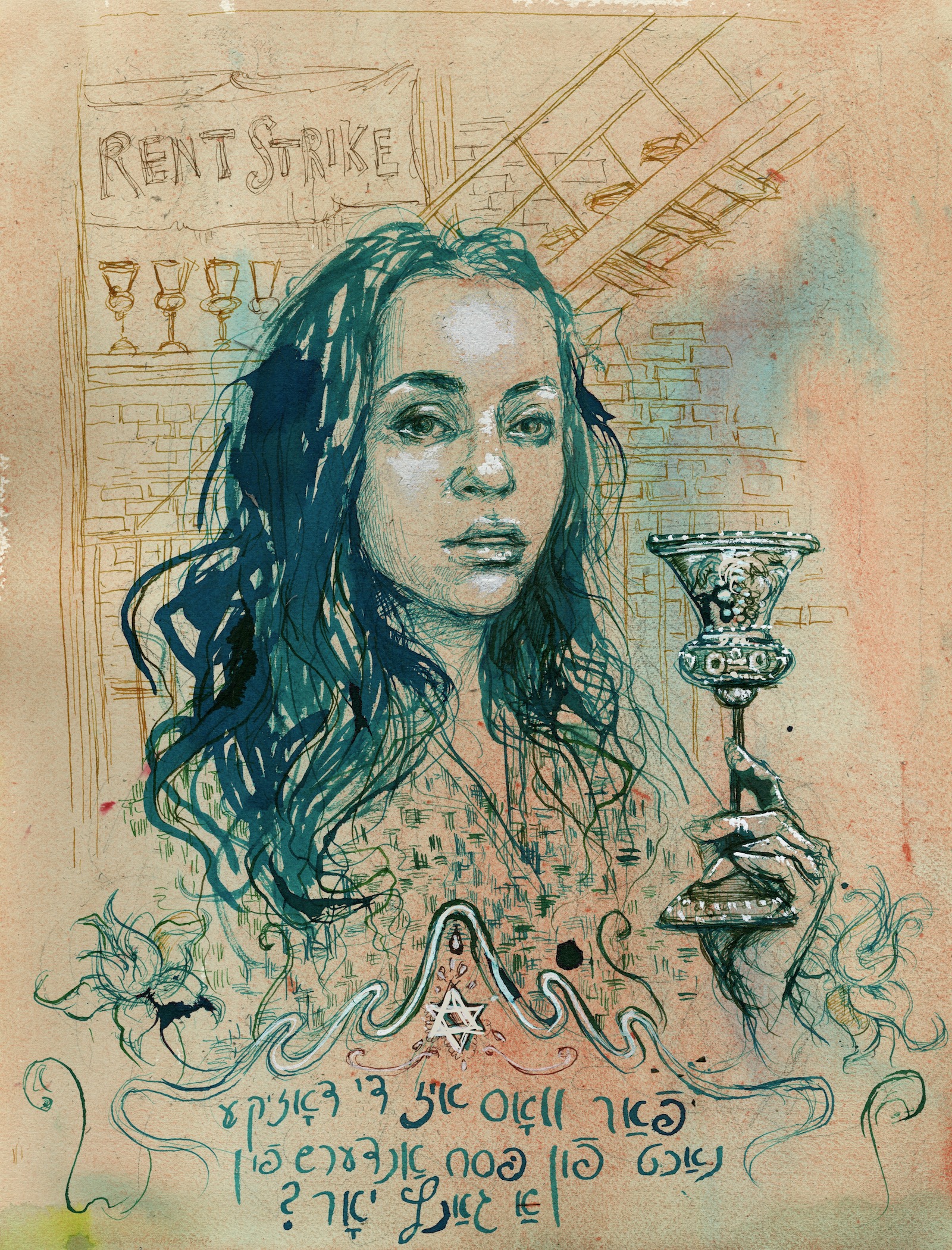

A few years later, she shook up our usual Sephardic seder with a new Haggadah, written by a Jewish woman who’d spent several years on a Navajo reservation. It was a stapled collection of grainy Xeroxed pages, illustrated with thin line-drawings of tree branches, iris flowers, and ouds floating above the familiar prayers in English and Hebrew. But there was one marked difference: chunks of her Haggadah lifted the Exodus story out of biblical times and into the politics of the present day, most notably reminding us that Jews in the Soviet Union were then “not free to learn of their Jewish past or to hand it down to their children.” The paragraph ended with a call to action: “As they cry out in protest, we add our voices to theirs.”

Over the years, I drifted away from regularly observing Jewish holidays. But Passover was one I rarely missed. It teased out the very best of my parents: my mother threw all she had into making my grandmother’s traditional Syrian dishes, while my father freed his inner crooner, belting songs like “Dayenu” in between swigs of wine.

As Covid-19 took hold in New York City, I started receiving emails from the rabbi at my local shul sharing digital Haggadahs and Zoom links to seders—connecting hundreds of people, their kitchens, their foods, their homes, across the city, to tell the Passover story together. The barrage of newsletters cracked open my claustrophobic anxieties. It was as though my aunt was standing above us again, shaking us out of our typical rote read-through, showing us how the world gets bigger when you open your eyes and notice other people in it.

It was with this in mind that I proposed to the NYR Daily editors that we should hear how others were going to spend the holiday.

—Marisa Mazria Katz

With seder guests: Etgar Keret in Israel • Anna Winger in Germany • Pamela Druckerman in France • Jonathan Freedland in England • Taffy Brodesser-Akner in New Jersey • Jenny Slate in Massachusetts

Etgar Keret

TEL AVIV, ISRAEL—I’ve never been a huge fan of Passover. Yom Kippur is my favorite, and Purim a close second. With those two, you’ve got room for some individuality: with Yom Kippur, you’re the one to decide what you’ll atone for; and with Purim, you get to choose your own costume. Passover, on the other hand, is a holiday at which you’re told exactly what and when to eat, and the story read aloud around the table allows for zero improvisation.

As a kid, I took Passover very seriously, especially because so much of the ritual is about parents’ teaching the story to their children. But, frankly, I didn’t completely get it: if the point was for the Jews, who were slaves, to have their own country, why did God make the Pharaoh’s heart so hard it kept him from letting us go? Could it be that God actually enjoyed torturing the Egyptian people? And what’s with the collective punishment? One would expect better from God.

I mean, couldn’t the guy get even with just the ones who had it coming? Imagine an ancient Egyptian pyramid contractor asshole with no kids: he’d be excused from the plague of the firstborn. But some nice Egyptian poet, who wasn’t really in on the Jewish slave trade, would lose a beloved son.

Looking at this story through coronavirus eyes, maybe the lesson here is: if you do something wrong, take responsibility for it. Admit it! It doesn’t matter if you’re an American president caught off-guard or an ancient people destroying the environment to build their pyramids. Admit your mistake and try to fix it. Anything else will just bring more plagues on your head.

Etgar Keret is an Israeli writer, comic book author, and screenwriter; his most recent collection of short fiction is Fly Already: Stories (2019).

Anna Winger

BERLIN, GERMANY—The last seder I attended was more recent than most—on a hot July day last year, in a house on the outskirts of Berlin, Germany. I was shooting a TV show about a young Hasidic woman. The interiors of this house served as the Williamsburg, Brooklyn, dining room of her grandparents.

More than a dozen cast members sat around a table in warm clothing, head scarves, and hats, the crew worked in T-shirts. All of them, illuminated by lamps from above, appeared as if in a Caravaggio tableau. For a whole day, the actor playing the grandfather told the story of our collective ancestors’ escape from Egypt in eloquent Yiddish. A child actor asked the four questions again and again. Between takes, extras in shtreimels smoked cigarettes outside.

Advertisement

Our real seders here in Berlin are typically less chiaroscuro, but no less crowded. One friend has puppets for each of the plagues. Another has perfect pitch. Yet another blows through the long-winded parts of the Haggadah like nobody’s business, impatient to get to the soup.

But this year, a real plague is upon us. It will just be the four of us around the table—my husband, my children, and me. To celebrate this holiday of all holidays alone truly underscores our strange isolation. It’s as if an imaginary eruv wire around the whole world is broken, there are no safe spaces left to move through, and everyone is stuck at home.

In Berlin, it’s never easy to gather what you need for a seder. This year, who knows? Maybe we’ll find a lamb bone, maybe a box of matzo, maybe not. Does it matter? I don’t think so. The story is what matters. The suffering of the Israelites gives us empathy, and their survival, strength. So we tell each other this story—over and over, this year more than ever, in every language.

Anna Winger is a creator and executive producer of the TV dramas Unorthodox and Deutschland 83, and the author of the novel This Must Be the Place (2008).

Pamela Druckerman

PARIS, FRANCE—There’s a Biblical commandment, Exodus 12:15, to rid your home of bread for Passover. Orthodox Jews take this seriously. Before the holiday starts, they don’t just give away their spaghetti; they also scrub down their refrigerators and vacuum their cars. Some open every book over a bin, in case someone ate a sandwich and dropped crumbs inside while reading it. Others boil or burn their kitchen utensils, to expunge the chametz (“most synagogues provide blow torches for this purpose,” one website says).

I was never very religious and only learned about the no-bread rule in my twenties. But I immediately embraced it. Lurking crumbs seemed like a metaphor for everything I disliked about myself: my failures at love and work, my penchant for wasting time. I kept this up when I moved to Paris and had kids. Sure, we ate shrimp pad thai the rest of the year, with only a passing thought that it was trayf, but not so much as a flake of croissant survived our annual de-breadification. I needed a purification ritual, offering hope that I could surmount my flaws.

Then came the coronavirus. Instead of using up our crackers and cereal in the weeks before Passover, I bought more. I was going into quarantine with three children: What if the supply chain collapsed?

As with many Jewish laws, there’s a loophole: you can keep your bread at home if you seal it, sell it to a non-Jew, and then buy it back after the holiday. But in lockdown, I’ve only seen my French neighbors, who, after eleven years, still address me with the formal vous. I can’t imagine explaining the chametz laws to them.

And then, there were suddenly too many invisible enemies in our crowded apartment. I was already making my kids wash their hands while singing “Happy Birthday”—twice. Should I also make them scrub possible chametz from our pantry? I decided that, this year, I wouldn’t worry about the no-bread rule.

Yet as Passover neared, I felt the old dread over having flour in my cabinets. I needed to hoard, but I also needed to purge. Before I knew it, I was bleach-spraying our kitchen shelves—remembering the rabbinic adage that a crumb doesn’t count “if even a dog wouldn’t eat it.”

I only felt better once I’d packed all my flour products into boxes, ready to be “sold.” I’m guessing that God won’t mind if I make only a verbal sales agreement with a friend, via Zoom. I won’t mention this to my children, who have enough to worry about.

Pamela Druckerman is a contributing opinion writer for The New York Times and the author of Bringing Up Bébé (2012).

Jonathan Freedland

LONDON, ENGLAND—Pesach, and especially the seder, is a tradition inside which nest many mini-traditions, peculiar to each family. Some are age-old, some relatively new. So there is the custom of starting the meal with a hard-boiled egg bobbing in a bowl of salt water—an egg for the coming of spring, salt water for the bitter tears of our slave ancestors. At our seder, that rite was matched for decades with another one. Each year, my father would take a bite and, savoring the taste, would ask, “Why don’t we eat this all year round?” Now that he’s gone, a new tradition has taken its place. “This is the moment,” his grandchildren will say, “when Papa asked, ‘Why don’t we eat this all year round?’”

Advertisement

Another of our invented traditions is for each one of us to recall our most memorable seder. For this, I always volunteered my Pesach on a Marxist–Zionist kibbutz in 1986, where the comrades celebrated the liberation of the Children of Israel thanks to the “outstretched hand” not of God, but of “workers’ power.” Now we’ll have a new answer. “This one,” we’ll say. “This is our most memorable seder.”

We will do it by Zoom: three of us in one house, four around the corner, a sister at the other end of North London, a son in Jerusalem, a niece in Tel Aviv. The virus will hover throughout, as it will at every seder around the world. We will dip our fingers in wine to recall the ten plagues, but we will be thinking of only one—that antique word, plague, rendered suddenly current.

We will recall how the angel of death passed over the homes of the ancient Hebrews, and reflect that, in Britain, Jews were, initially, felled in disproportionate numbers by coronavirus. And we will pause at the tenth plague, the slaying of the first-born, reflecting on how many, first-born and otherwise, have already been lost.

But I wonder if the most pointed moment will come at the very end, when, having attempted a singsong by wobbly video-link, we will conclude with the chant that wishes “Next Year in Jerusalem.” Every seder, somebody explains that this refers less to the literal Jerusalem than to the notion of a world at peace and in harmony. I don’t think even that symbolic meaning will be front and center this time. I, for one, will have a more modest goal in mind. Just as the Queen struck a chord in British hearts with her TV address on Sunday night, referencing an old wartime song to reassure her subjects when she said, “We will meet again,” I will sing that closing Jerusalem anthem with a single hope: that next year, we will be together.

Jonathan Freedland is a columnist for The Guardian, a contributor to the Review, and the host of the BBC Radio 4 history show “The Long View.”

Taffy Brodesser-Akner

NEW JERSEY—I was raised in an Orthodox household, and it’s been a real journey for me to find how I like to observe Passover in general, and do the seders in particular. We’ve been guests of dear friends in Los Angeles every year for the past several. We used to live there, and we love visiting our Jewish community in LA, where most of our close friends still are. But we weren’t going this year because my book tour, and a few bar mitzvahs, were already taking us there this year, so we figured we’d skip it just this once. And so, in fact, our seder was to be on our own.

Nothing will be different for us. We won’t use Zoom, since the people we’d like to celebrate with are Orthodox, and wouldn’t use that kind of technology on a holiday. My husband and sons, as we speak, are cleaning our house. We ordered Tablet’s new Haggadah, which I’m very excited about. We’ll hide the afikomen; we’ll sing “Dayenu.” We’ll allow Elijah into our homes (he’s been in self-isolation for the last year-less-eight-days).

But here’s the thing I’m specifically doing that’s not so much different but intentionally the same: it’s so easy to try to find metaphor in the service—we ask ourselves questions on the side like, “What do we feel personally enslaved to now? Material items? Work? Certain ideologies?” We do that so that we can feel closer to material, which feels more and more distant as the centuries go by. It’s hard to relate to a life of slavery in Egypt now we live in the boom of the twenty-first century America. But I think it’s important to work hard to resist metaphor, since the point of the seder is to remember the actual slavery. When we choose to see it as metaphor, I feel it’s a way of apologizing for participating in a remembrance that seems almost tacky today: American Jews are so far from slavery now. But the point is to remember it, to rejoice in the fact that it’s no longer our burden, to see it coming again. So what I’m going to do this seder is to conduct it like any other seder, which is to remember that we were once slaves and we no longer are. We will discuss the “Great Indoor Experiment” another time, but we will not make it part of our seder. This seder has plenty to contend with.

Taffy Brodesser-Akner is a writer for The New York Times Magazine and the author of the novel Fleishman Is in Trouble (2019).

Jenny Slate

MASSACHUSETTS—Yes, this is an appropriate time to sing “Let My People Go,” and it also seems appropriate to go right ahead and smear our doorposts with blood, to mark our homes, and say, “Not us, please.” But why should you have to tell an angel not to kill your family? That is the part of the Passover story I never understood. Can’t anyone just get a break? If you’re an angel in charge of death—and you are important enough to know God—why are we the ones who have to ruin our house by putting blood all over it? Why doesn’t the Angel know us?

I used to celebrate Passover with the traditional two seders, and the keeping of Passover itself. I don’t anymore, but there is one thing I will do for the holiday: stand in my doorway and open the door to the Prophet Elijah, because I believe that that moment is real, and I’m glad it is striding toward me, even now.

When I was a girl I would stand at our open front door, knowing that in the day, I had seen the thaw of spring in the little rips of green on the dull brown boughs. I had sensed that the deep-ruby-bodied worms were turning the soil for us in preparation for the swinging in of spring, but that now, as I stood at the door, there was nothing but the slap of the night, a scoff of wind.

I was standing as a sentry for an approaching ghost who was being pulled in on the rope-y wailing song of a singing family at the other end of the house. This year, on Passover, I will open my door and stand in the dark, put my body in the palm of the hand of the night, and feel very young, and see if I can feel the spirit slipping past me to sit in an empty chair in my home.

Then I will go inside and I will sit across from whatever it is, and I will try my hardest—for the first time in weeks—to sit with what frightens me, with what I cannot control. I will know that, while I am not capable of having this holiday as it should be had, I did keep some tradition. I will feel that I honored those family members who taught me you can have a day full of spring, and an evening of reciting the story of our rescue, but after all of it, you must accept that scary things still need to be granted a seat. You must be brave and dignified enough to open the door to what is still walking in the dark.

Jenny Slate is an actor, comedian, and writer. She co-created The New York Times best-selling children’s book series Marcel the Shell with Shoes On, and her most recent book is Little Weirds (2019).