Moor: an area of open and usually high land with poor soil that is covered mainly with grass and heather, says the dictionary. Its synonyms are fell, heath, and the Scottish muir. Some people think moors are bleak because of their treeless expanses, low vegetation, and apparent lack of wildlife. They are not charmed, or worse. On maps, the moors of northern England are not distinctive. Even on the most detailed Ordnance Survey maps, they are an undistinguished beige; you can guess at them by the contour lines or the map symbols that signify bracken or marsh. There is rarely any green, as for woodlands or farm fields.

In English literature and history, the moors are associated with the Brontë sisters, but also with Ian Brady and Myra Hindley, a vile pair known as the Moors Murderers, who tortured and killed five children in the 1960s, then buried them on Saddleworth Moor, outside Manchester. One boy’s body has never been found. The expanses, the harshness, the lack of shelter: I see that the moors can seem forbidding. “As you value your life or your reason,” an anonymous letter warns Sir Henry Baskerville in Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Hound of the Baskervilles, “keep away from the moor.”

But to me, as I run them, my local moors are beautiful, and I love them with abandon: Rombalds, possibly named for an ancient giant, and its subsections of Ilkley, Baildon, Burley. Burley Moor is only twenty minutes’ drive away for me, up the A65 road, which runs northwest for seventy miles from Leeds, my home, through the Yorkshire Dales to Kendal in the Lake District. On the other side of the A65 lies a stretch of moorland between Beamsley Beacon, where a Lancaster bomber crashed a few months after the end of World War II, killing four of its Canadian air crew, and Round Hill, so bluntly named yet no rounder than any other hill.

I run and race often on these moors, and I know many of their paths and “trods”—a word I fail to find in a dictionary but which is common as muck among the people who walk the moors and hills to denote an informal narrow pathway trodden into definition by sheep. (And if you say trod, then you also say clag and clough and beck, for fog, gully, and stream.) I know the moor’s carved stones and standing stone circles. I know the Badger Stone and the Swastika Stone, a Bronze or Iron Age carving from a time when the swastika was a general-purpose auspicious symbol, before the Nazis flipped and tainted it. I salute, always, the dozen rocks that make up the Twelve Apostles, which are stumpy and stubborn in proper Yorkshire fashion, yet somehow magnificent and calming.

I try to listen to more than the sound of my breathing. (I never listen to music: Why muffle nature?) There are nature writers who can put words to everything they see and hear; I don’t have their knowledge, but I can still delight in the call of a bird I can’t identify. Is it a curlew? A meadow pipit? Is that plant a bog asphodel or a sundew? At least I can tell when I’ve surprised a grouse.

And I do have some moorcraft, learned through years of mistakes: I know never to trust a bog or a puddle that I can’t see to the bottom of, but I know, too, that clear water can be trickery—a clear puddle once concealed a bog that trapped me fast for what felt like many minutes during a race, until two strong fellow competitors hauled me out. For sure footing, I know to step on the grass that grows amid water because it has strong roots, but not on what I thought of as “that spongy shit” until I looked it up recently (it is sphagnum moss), because it will always betray me and my foot will sink and me with it.

I am never bored on the moors, and in the wildest conditions I never find them bleak. Their beauty is just not flashy. I like the indifference. Moors, wrote Ted Hughes, “are a stage / For the performance of heaven. / Any audience is incidental.” I like the moors for the same reason I love to be at sea: I matter less in all this. It is a relief.

But today, the moors are impossible to reach. Under the official coronavirus regulations, “to take exercise either alone or with other members of their household,” is the second of thirteen justifiable reasons people can leave their homes. Official messaging since that mandate came into force, though, has implored people to exercise only once a day and to stay local: leave from your house, but not with your car. This has been enforced by some local police forces leaving stern shaming messages on cars they find in beauty spot parking lots; other forces have taken to photographing walkers on the hills with drone-mounted cameras, then shaming the people on public media.

Advertisement

The order to stay local has mostly sunk in, which is odd since it doesn’t exist in law, which sets out no restriction of time or distance (except in Wales, where it does). Still, we all want to do our bit. But apparently, we also all want to exercise. It must be our way of grabbing one of the few legal ways of being outdoors. It’s there; so we take it.

Partly, we are also absorbing the message that exercise is good for our immune system. I see the new walkers and runners: the new runners are easy to spot by the fact they stare at the ground, and the women’s sports bras aren’t as good as they should be.

Yet there is also selfish defiance. On motorways heading to the Lake District and other “areas of outstanding natural beauty” (one of my favorite terms of officialese), people in campervans are being turned back. But others are still heading to the beaches and into nature, no matter how many drones are following them.

*

I understand the lure. I am a fell runner. A fell, from fjall, Old Norse for mountain, is properly a Lakeland term, but fell runner is used to describe anyone who likes running in wild places, not necessarily on paths, and with fewer rules than apply in most cross-country or road races. In a fell race, you can usually make your own route between one checkpoint and the next, and if that route includes running through knee-high heather or jump-running your way between tussocks, or pelting down a scree slope, then so much the better.

I do not live in the Lake District, so probably I should call myself as the Scots do, a hill runner. Hills, fells: it doesn’t matter, because their long curves of brown and purple heather and tricky technical rocks are for now equally unreachable. It is hard to explain fell running to foreigners: Is it mountain running? No. Is it trail running? No. It is different. The landscape, the tribe, the elements, the freedom: they are addictive. I don’t know many road runners who come to the fells and then return to asphalt.

I came slowly back to running, and then to fell running. Of course, I didn’t need to be taught to run; most children don’t. We run freely and in the best form of our lives in childhood, before growing up sits us down and switches off our muscles and life gets in the way. Running disappeared for me until 2010, when I found myself a passenger on a container ship for five weeks (while researching my book Ninety Percent of Everything). No exercise was allowed on deck, but there was a gym with a treadmill. I was forty-one years old, and I learned to run again, for fun.

Nine years on, I run twenty or thirty miles every week. My greatest pleasure is to fetch up to a race on a weekend, to get myself up some great hills, and to zoom down their sides with unfettered joy. Mud, bog, rain, hail, sun, gorse: it is all exhilarating. That I am fifty years old, and in menopause, makes the pleasure of careering downhill somehow even more acute.

There is nothing better, I think, than the mug of hot soup you’re handed after a winter’s fell race, when your skin is tingling and your legs are tired and your heart is happy. There is nothing less grand than a sport that takes place in the grandest landscapes, where winners and back-of-the-packers mingle equally because the nature of the sport—the risk, the weather, the joy—is shared and makes us equal. And none of us is above getting changed out of the trunk of their car, in driving rain, on the exposed height of Penistone Hill on Haworth Moor.

*

Wild landscape was the only thing I finally came to miss after weeks at sea. It is the only thing I miss now. It’s no use my looking at maps and remembering places I have run, and reading the hill names with sadness. I am being a good citizen, and so I must run nearby, and make do with what my city can offer me.

Advertisement

Luckily, it has enough for now: I live in the northern reaches of the city, which used to be countryside and isn’t far from it now. There are woods a mile from my door, and fields and reservoirs only a little further north. They are familiar but not too much so yet; I can still find variety by taking a new footpath, or running in a different direction around a well-known loop. I stop and read signs in woods that teach me about a water-fountain called the Slabbering Baby; I read the local map for revelations, to learn where to look for the city’s trig points, the surveyors’ pillars that denote its highest places.

These days, with traffic so reduced, I even run on roads, as they can be quieter than parks or popular trails. There is even entertainment to be had on streets that would before have bored me, as we all gamely play avoid-each-other bingo, stepping into the road, or crossing it.

I haven’t always got it right. Last week, on a Sunday, I ran in woods that are normally quiet. But it was the first Sunday of the lockdown and they were not empty. I try always to find a way of alerting walkers that I’m there, and usually fail. This time, as usual, my “coming through, please!” was at first too quiet and polite, and then too loud and startling. The three people in front of me jumped, then moved. I paused as I ran past them, between a man and his elderly mother, to apologize, and I couldn’t understand why the man had glared at me. For several hundred yards, I cursed him in my head, but he was right to be angry. I had stopped too close, and I had breathed and sweated and spoken, to one of the most vulnerable.

I felt terrible, and haven’t let it happen since. Friends of mine who are walkers now use words like “hate” and “despise” to describe runners who do not give them adequate warning or space. Runners hog space, they say; they spit; they come too close; they breathe too hard. Running—detractors show their distaste by calling it “jogging”—is, wrote The Times, “an unhygienic flurry of panting and spitting.” You want runners not to breathe?

I find the blanket hostility disheartening, but people have grounds for fury when there definitely are runners who do not give good warning, or who do not run at a safe distance, or who spit. And people are scared, so finding scapegoats always seems to help with that. This is particularly true when outside space is either overcrowded or threatened. All the vitriol for runners here comes from densely populated cities. Yet some city authorities, from London to Los Angeles, have closed parks or trails. Where are people to go?

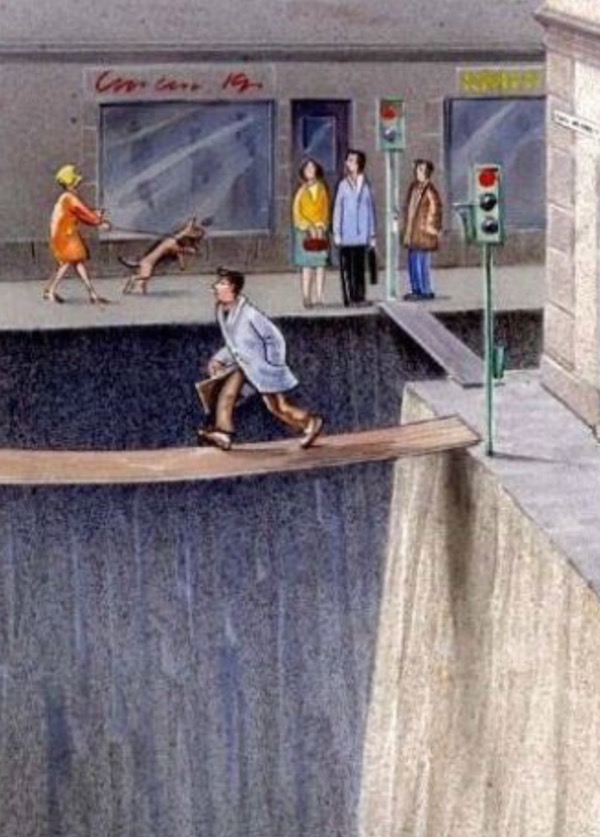

I would wager that most of those running space-hoggers and spitters are men. Even in normal times, most women have encountered men who ostentatiously dominate a sidewalk: mobile manspreading. This is when sidewalk space is already minimal, as so many cities prize cars over pedestrians, leaving them slivers. A recent illustration from Sweden that has been circulating on Twitter showed this perfectly by turning the road into an abyss, showing foot-travelers picking their way around the edge of a precipice that is all our allotted space. At least the pandemic has forced some city-planners to rethink, however temporarily. Mayor Bill de Blasio has pedestrianized some of New York’s streets, but only at weekends. The city of Calgary in Canada has done the same thing. Berlin has added to its bike lanes.

The rest of us must make do with what we are allowed, and hope the reduced traffic and quiet streets continue beyond lockdown. I wish another new habit would also remain. Living in a city has always required negotiating with what the sociologist Erving Goffman called “civil inattention,” because to be attentive to millions of fellow residents is impossible and exhausting.

My city is home to some 800,000 people, but its spread is large and most areas are not densely populated. There is room for all. Yet, in normal times, even in this small city—the third largest in the country but still small by the standards of international megalopolises—people don’t greet each other. No eye contact, even in green spaces. It requires people to cross the invisible barrier between city and countryside for that to change: as if they step through a door to a place where it is safe to see and value a stranger.

On the moors and hills, greetings are routine, with words or a look or a nod that would have been impossible half an hour earlier on a city street. I like these signals that we are sharing an experience, that we have chosen to be here outside, up above, and that it is a good choice. Now the virus has brought those countryside customs to the newly spacious city streets and footpaths. Fellow humans are more scarce and therefore unthreatening. It is safe to say hello, and most people do. This will not last. I’d like to pretend it could, but I know it won’t.

This morning, I ran around one of my local city parks, where I encountered only a couple of dozen people. We all veered out of one another’s ways, and I thought how quickly we have adapted to new customs that are actually profoundly alien. And so we will quickly drop them, too, when this is over. But I will be back on the moors, with the grouse and the bogs, where the rules are different and the unforgiving wildness makes for kinder humans than cities do.