When Joseph Brodsky got off the plane in Ann Arbor, Michigan, in 1972, as an exile from the Soviet Union at the age of thirty-two, imported by his friend, the Russian professor and basement publisher of censored writers Carl Proffer, he already had a head full of poetry in English, as well as American movies and jazz, Italian painting and architecture, Greek and Roman mythology, and on and on. A steady diet of Soviet conformity and canned ideology had driven Brodsky from school in Leningrad while he was still a teenager, and an aversion to acquiescence had bumped him through a series of menial jobs and paycheck-pursuing junkets. This trajectory ultimately landed him in compulsory internal exile in a remote farming village in the subarctic district of Arkhangelsk. Throughout, he had harbored a slow-burning, private vocation as a reader. His father preserved the ziggurat of books and bookshelves and accumulated literary artifacts with which the young Brodsky walled himself off from the rest of his family’s komunalka (communal apartment) in order to read and write into the night, conveying the jumble intact to friends. With the lifting of Soviet censorship of Brodsky’s work in the Nineties, those custodians passed it into various archives where it lingers now.

Brodsky shared this abundance of reading—as wide around the world and as deep into the past as he could go within the constraints of Soviet publishing of the time—with his peers, a generation of young Russian intellectuals peeking warily over the edge of the war’s ruins, hungering for art and knowledge and experience to press against the “trimming of the self” required by the state. They hand-typed forbidden books with multiple carbons and squinted at them through the dark glass of translations that had just barely squeaked in by way of Poland. Brodsky wrote of his generation:

This generation was among the most bookish in the history of Russia, and thank God for that… It started as an ordinary accumulation of knowledge but soon became our most important occupation, to which everything could be sacrificed. Books became the first and only reality, whereas reality itself was regarded as either nonsense or a nuisance. Compared to others, we were ostensibly flunking or faking our lives. But come to think of it, existence which ignores the standards professed in literature is inferior and unworthy of effort. So we thought, and I think we were right.

Amid this tumult of curiosity and aspiration, pursued in relentless reading, in late-night kitchen disputations, with stealthily befriended foreign students and travelers, and by lamplight in the countryside, one realization was coming into focus for those who read and conversed below the official radar: young Brodsky was a prodigy in the composition of verse. Russian poetry was relatively green by European standards; its forms had stabilized in the nineteenth century when most of the Russian elite spoke French. The charmed generation of Russian poets who corresponded to the English and European Romantics—most famously Pushkin, but also the surrounding constellation that Brodsky and his friend Alan Myers anthologized in a short handbook for beginners, An Age Ago (1988)—were pioneers who had the advantage of ploughing fresh ground. While English Victorian poets like Tennyson and Browning were sounding a weary and self-conscious note, their Russian counterparts were still within view of their poetry’s beginnings, and their engagement with its formal devices remained fresh.

The Russian language had additional advantages feeding the vitality of its poetic means: Russian is a highly inflected language, so word order is variable; and its system of internal stresses is much more flexible than English, allowing for more variety in patterns of rhyme and meter. When Brodsky’s immediate predecessors—poets such as Boris Pasternak, Osip Mandelstam, Anna Akhmatova, and Marina Tsvetaeva—were struggling with the murderous violence of the Bolshevik regime, they looked to the resources of Russian prosody as a repository of universal and civilized values. To compose in classical measures was an expression of solidarity with a continuous tradition of artistic individualism and defiance, as well as solidarity with worldwide aesthetic ideals against the enforced pragmatism of Soviet ideology. Brodsky wrote, “Russian poetry has set an example of moral purity and firmness, which to no small degree has been reflected in the preservation of so-called classical forms,” and, he went on:

… verse meters in themselves are kinds of spiritual magnitudes for which nothing can be substituted. They cannot be replaced even by each other, let alone free verse. Differences in meters are differences in breath and in heartbeat. Differences in rhyming pattern are those of brain functions.

A poem was more than its semantic meaning, he insisted: “poetry amounts to arranging words with the greatest specific gravity in the most effective and externally inevitable sequence… it is language negating its own mass and the laws of gravity; it is language’s striving upward—or sideways—to that beginning where the Word was,” aspiring to its “highest form of existence.” And of course for readers living under censorship, for whom memorizing poetry was as necessary as it was for the ancients, the mnemonic power of musicality in verse contributed to its potency.

Advertisement

Self-educated, intense, impulsive, unmoored, Brodsky emerged into this setting as a poetic virtuoso; he did things with Russian verse that no one had thought possible. His mentor Anna Akhmatova, revered for having asserted her poetic autonomy even when threatened with death and imprisonment, immediately pronounced him the carrier of the embers of Russian verse, which doomed him to unwavering attention from the authorities. Others of this cohort, precisely because their commitment was to art, had proved themselves quite ungovernable and were continually in the crosshairs of the state.

Brodsky took the medium of formal poetry—capable of high lyricism, polished to an imperial shine by the wryly skeptical Pushkin and his circle, molded to the agonies of war and oppression by Akhmatova and her generation—and lashed it to a modern sensibility. His idiom embraced classical poise, Biblical gravitas, philosophical disenchantment, and street slang. Within the confines of his book-walled lair, he searched the world for models and peers, coming to rest on English as a needed counterweight: a tonality that was quotidian and anti-hysterical, a mighty tradition nested in a gentle landscape.

He wrote early poems eulogizing T.S. Eliot and John Donne. But it was in the simple farmhouse of his exile in the northern province of Arkhangelsk, where a friend sent him Oscar Williams’s New Pocket Anthology of American Verse, that he forged during long nights of reading his two most enduring poetic kinships: with W.H. Auden and Robert Frost. He assimilated their practice, using poetic form to dampen grandiose effects and to access a more chastened, open-eyed humanity, into a lifelong poetic position. He later wrote of Auden, “The way he handled the line was telling, at least to me: something like ‘Don’t cry wolf’ even though the wolf’s at the door. (Even though, I would add, it looks exactly like you. Especially because of that, don’t cry wolf.)”

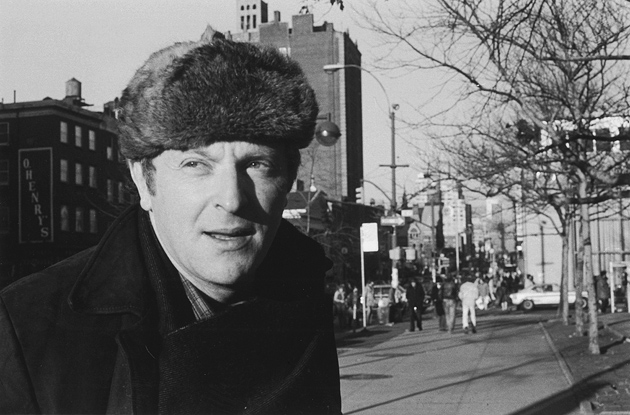

When Brodsky left Russia as an involuntary exile, he at first feared that, severed from the daily encounter with spoken Russian, he would not write another poem. His trajectory had in a sense been inevitably international—he had always yearned for Italy, too, the grandeur of its classical proportions and fragmented inheritance—but history dictated that his journey be one-way. Promptly upon his arrival as a rather improvisatory literature professor at the University of Michigan, he embraced the American demotic and became a presence in American poetry, offering a riposte to the anti-intellectualism and colloquialism of the Seventies and a revitalizing assurance of the ascendancy of art in a society that too often associated learning with elitism. The Brodsky who arrived in Ann Arbor in 1972 with one suitcase was nobody’s establishment.

Brodsky confronted the situation of exile as an amplification of the existential charge that animated his sensibility. He was a poet of open eyes, who had no patience for consolations. To be lonely, to miss your family, your friends, your love, your language, your streets, your familiar sensations, was to be thrown into the reality of the solitude that is the universe’s message. His exile took his twin themes of travel and time and fused them: the past is a place to which you cannot return; the future is a place of infinite emptiness. His love for Italy, where the past is everywhere around, offered a glimpse of refuge, most poignantly expressed in the comprehensive elegy, “Vertumnus,” in which art is “some loose / silver with which occasionally rich infinity / showers the temporary” and in which “a sellout-resistant soul / acquires before our eyes the status / of a classic.” If his task, and his poetry, became more difficult, it was because they were driven to address a more difficult truth. Only in his very last poems does the possibility of home and arrival flicker on the horizon.

Brodsky wrote four books of poetry in Russian while in America, in addition to publishing in exile two books of poems written previously. The first book in English that he was able to oversee as author, A Part of Speech (1977), was an elaborate symphony of collaboration. Editors at Farrar, Straus & Giroux secured literal renditions of many of the poems and sent these to the poets with whom Brodsky felt the greatest affinity—Derek Walcott, Richard Wilbur, Anthony Hecht, Howard Moss—who crafted them into English that Brodsky, with his own growing command, then revised. Other translations were the product of long collaborations. By the time of To Urania (1988), Brodsky was taking a greater hand in the proceedings. His approach to his poetry in English has come under fire, criticism to which he used to reply that his Russian reviewers (often from hostile officialdom) leveled similar complaints—that he forced the outcome, that he overran conventional uses of language, that he was dissonant. I’d advise readers to consider this analogy and question the enforcer within: Brodsky’s English may challenge the reader’s ear in ways that invoke unfamiliar powers in poetry and so reward the challenge.

Advertisement

In 1983, Brodsky wrote the essay “To Please a Shadow,” in which he described buying a Latin-font typewriter in order to close the distance between himself and his beloved Auden. When Brodsky had landed in Vienna on his way out of Russia, Proffer had taken him to visit the poet he had come to revere in that sub-Arctic farmhouse; this encounter punctuated an internal dialogue lasting well beyond the two poets’ few years of friendship. Brodsky used to quip that he was a Russian poet, an English essayist, and an American citizen. His English essays, published in two volumes in his lifetime as Less Than One and On Grief and Reason, in addition to a long prose reflection on Venice called Watermark and some scattered uncollected pieces, offer a window into a restless mind in which English and Russian are constantly unfolding, viewed through the atmospheres of still other languages and milieux.

We now live in a time of which Brodsky was an advance scout—a time in which many writers operate beyond their original borders and outside their mother tongues, often, like Brodsky, bearing witness to violence and disruption, often answering, through art, to those experiences, in language refracted, by necessity, through other language. In Brodsky’s time there was a cluster of poets, some from the margins of empire, some, like Brodsky, severed from their roots—Walcott, Heaney, Paz, Milosz, to name a few—who brought with them commanding traditions as well as the imprint of history’s dislocations. We would do well now to attend to their song, standing as they did in our doorway between a broken past and the language’s future.

Joseph Brodsky: Selected Poems, 1968-1996, edited by Ann Kjellberg, will be published this month by Farrar, Straus and Giroux.