MINNEAPOLIS—Police on the roof of a building, firing rubber bullets at the crowd below. Angry protesters in helmets and padded lifejackets. Intersections littered with teargas canisters. Middle-aged women pulling off their protective Covid-19 face masks to douse their stinging eyes with milk. Storefronts smashed; acres of downtown real estate in flames. More teargas. More anger. An emotional mayor asking for the prosecution of a member of his own police department, then calling in reinforcement riot squads. Pepper spray and stun grenades. Hundreds of National Guard troops arriving in convoys to restore order to the streets.

In the three days since the horrific death in police custody of George Floyd, an unarmed black man, in broad daylight, Minneapolis has been transformed almost beyond recognition. From an outwardly calm, notably progressive metropolis—a city led by a young, liberal mayor and a black police chief—it has suddenly felt more like civil-rights-era Newark or Detroit. A place where police spray mace indiscriminately on pedestrians from a squad car window; where people have ransacked Targets, Walgreens, and many other local businesses; where the sounds of stun grenades and helicopters and emergency sirens can be heard at any hour of the night.

For many Twin Cities residents, the speed of the unraveling, from above and below, has seemed almost unfathomable. It began on Tuesday, in the mostly working-class neighborhood of South Minneapolis, where Floyd’s fatal encounter with police took place. Driven by a powerful upswell of outrage, thousands of ordinary residents, people of all ages and backgrounds, wearing face masks and bearing signs, broke quarantine and gathered in a peaceful march from the corner store next to where Floyd had been arrested and pinned to the pavement by officers to the 3rd Police Precinct two and half miles away. Yet, already that evening, the first protest had ended, hours later, in a teargas skirmish with police. By the following night, multiple stores and buildings around the precinct had been set on fire. By Thursday afternoon, the unrest had spread across the river to several areas of St. Paul as well, to the point that the US Postal Service suspended delivery service in large parts of both cities. Then, shortly after ten on Thursday evening, groups in Minneapolis set fire to the police precinct building itself, forcing the mayor to order its evacuation as it went up in flames.

For the thousands of local residents who have braved both the pandemic and the threat of violence to take part in the protests, the situation has presented unprecedented challenges. “I try to be prepared, I’ve got my goggles, helmet, a thing to protect against rubber bullets, but it’s treacherous out here,” the local civil rights activist and attorney Nekima Levy Armstrong commented on Wednesday, as posted on Facebook. By Thursday evening, even before a CNN crew was arrested while reporting the disturbances, local news photographers were themselves retreating from some of the worst encounters; one reporter complained that there was so much teargas that it was hard to estimate crowd numbers. A local friend who has reported in Iraq and elsewhere said that he was having flashbacks to actual war zones. Two of the supermarkets where I habitually shop were attacked yesterday; early this morning, the drugstore down the street was burning. Surveillance helicopters have been circling for much of the past twenty-four hours, the storefront of the local hardware store has been barricaded from ground to roof out of fears of what the authorities are describing as “flash looting.”

But as community activists have noted, however extraordinary the week has been, both the anger, and the heavy-handed response to it, has much deeper origins. In 2016, the police shooting of Philando Castile in nearby Falcon Heights, a suburb of St. Paul, drew national attention. But the suffocation death of George Floyd—a man who cried out, in his dying words that he couldn’t breathe while an officer held his knee to his neck for minutes on end—is in fact the fifth police-involved killing here since 2018 alone, when the current mayor of Minneapolis, Jacob Frey, took office. As with Floyd and Castile, nearly all of the recent cases have involved black citizens. Until now, however, in only one of the cases has an officer faced criminal charges, and that involved a white woman and a black police officer. Behind such a dismal record of failed accountability, there is by now a widespread sense that structural racism in the city’s administration and law enforcement runs deep. Amid the present public health crisis, with a restive population and rising unemployment, the brazen killing of Floyd this week has brought public anger at the city and “the system” to a breaking point.

Advertisement

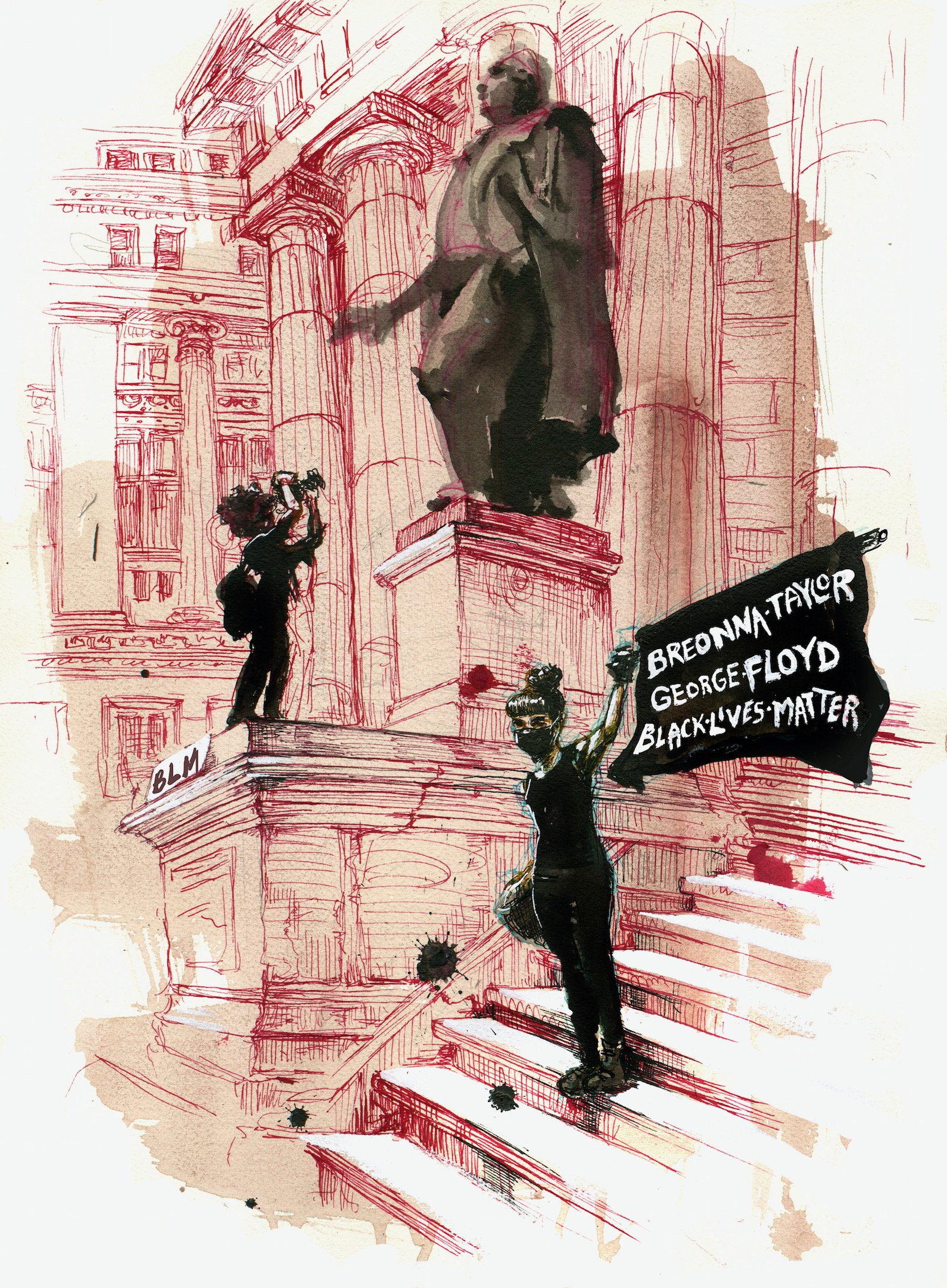

What has been lost, though, in all the shocking images of fires, police barricades, and looting is that an overwhelming majority of protesters have condemned the violence and have sought to bring the community together. Each morning, large groups of citizens have spontaneously come out to help clean up the streets around the main protest area. Even on Thursday, while the national media trained its attention on a roving group of fifty or so people looting Target and other stores in the Midway neighborhood of St. Paul, a far larger, entirely peaceful demonstration, involving more than 2,000 people, unfolded for hours, in front of the Government Center in downtown Minneapolis. (On social media, veteran local activists also noted that the location of the Midway attacks was not accidental: the shopping center is near the heart of what was once the city’s main African-American neighborhood, a community that was blighted by the construction of the invasive interstate in the 1960s, and has suffered economically ever since.)

Many now fear that the simple demand for justice for George Floyd—a call so basic and obvious that Mayor Frey himself, within forty-eight hours of the event, was publicly asking, “Why is the man who killed George Floyd not in jail?”—will be subverted by the mayhem and by the almost unimaginable militarization of the city’s response to it. In the worst of ironies, outrage at the system has, at least for now, made the system more terrifying than ever. Across social media, peaceful protesters have expressed unease that the police are no longer there to protect them, that—as much of the black community has sensed for years—the police are menacing, heavily armed antagonists. For its part, the city authorities have struggled to maintain a semblance of order, without provoking yet further unrest—even as the president sends inflammatory tweets threatening more lethal force.

But the greater tragedy of the Floyd killing, and its aftermath, may be yet to come. As the epicenter of the state’s Covid-19 pandemic, Minneapolis was already contending with far-reaching health and economic issues when the unrest began. The virus itself has seemed to demonstrate the hidden racial injustice that many have long observed in the state: though they account for only 6 percent of the state’s population, black Minnesotans have accounted for nearly 30 percent of known cases of the virus, according to data published in The Star Tribune this week.

This is but one more example of the abysmal structural inequities that have quietly plagued the city and the state for years: according to the most recent census data, average income for black households in the state is less than half that of white families; while homeownership among whites in the Twin Cities ranks among the highest in the nation, at 75 percent, black homeownership is just 23 percent; and while the state’s population is among the most educated overall, it also had one of the largest attainment gaps between whites and blacks in the country. For much of the past two months, the city has seemingly taken the pandemic in stride. But cases are still on an upward trajectory here, with ICU beds already at, or close to, capacity. Barely noticed on Thursday, amid the protests and violence, was the alarming disclosure from the state that it had registered its largest single daily death toll—thirty-five people, bringing the overall total to a thousand deaths—since the pandemic began.

Already, state health experts have warned that the large-scale protests this week could themselves lead to a rapid spike in infections. Equally hard to ignore has been the toll of the violence on local businesses, already struggling to survive during quarantine. In the neighborhood around the protest site, one particularly bitter outcome was the burning to the ground of a nearly finished, affordable housing complex that was supposed to be ready for occupancy later this year. It featured 189 units, of which several dozen had been designated for tenants of very low income. Now, it is razed.

As people across the city look for justice, one thing seems certain: a de-escalation is desperately needed, but holding the officers who killed Floyd to account will not be enough. The city will finally have to address the persistent and pervasive racial injustices that have, after so many years of neglect, now exploded into full view.