Minneapolis, Minnesota—State Attorney General Keith Ellison came a little late to the Juneteenth Friday prayers at the state Capitol in St. Paul. It was a cloudless, 80-degree day, and he discreetly joined a few dozen worshippers on the pavement in front of the imposing statehouse and unfurled his red prayer rug. The gathering was billed as a “Jumu’ah for Justice” by the Minnesota Muslim American Society, Jumu’ah designating the midday Friday prayer, the most important and ceremonial one of the week.

It had been twenty-five days since George Floyd was murdered by a police officer outside a convenience store and Minneapolis erupted in protests that spread worldwide. The service itself had not started yet; in step with the general mood of public life in the Twin Cities this past month, the meeting was fused with a racial justice rally. A round of speakers passed the mic, extemporizing about police brutality and structural injustice. The families who had assembled to pray were Somalis, Arabs, South Asians, Southeast Europeans, African Americans. They sat beneath a statue of Knute Nelson, the Gilded Age Minnesota governor best known for stripping millions of acres of tribal land from the region’s native Ojibwe. Several hundred more protesters and spectators lolled nearby on the lawn.

A black Yemeni refugee, Zaynab Abdi, in a mustard yellow tunic and dark green hijab, took up the mic to say: “I came here in 2014, at the beginning of Black Lives Matter,” with an air of authority belying her slight frame. “I’ve seen the revolutions in Yemen and Egypt. Seeing the National Guard here reminded me of the tanks I’ve seen there. We don’t want this to happen here. We can’t let this system militarize us. We can’t let them shoot us because we’re asking to breathe. We can’t talk about human rights abroad, when we don’t have it here.” She received uproarious applause.

Ellison arrived around 1:30 PM. As attorney general, he is now one of the most high-profile officials in the state. Governor Tim Walz asked him to take over as special prosecutor on the George Floyd case. Ellison, who is black and Muslim and has a long history as a civil rights activist and lawyer, responded unusually swiftly, charging police officer Derek Chauvin with second-degree murder and three other bystanding officers with aiding and abetting it.

On the Capitol lawn, a woman crossed her arms and, pacing impatiently, said: “This isn’t right.” Toya Woodland, a middle-aged minister at Christ Temple Apostolic Church and a Black Lives Matter activist, was dressed in all white, wearing ripped jeans and Air Force One sneakers. “Are any of you guys here for the reparations rally?” she asked, addressing the protesters on the lawn. “This ain’t right,” she said, several times, brimming with emotion. “This is our day! Juneteenth.” This widely publicized event, organized by Black Lives Matter Minnesota, was indeed why I had come down to the statehouse. It turned out that the Muslim American Society (MAS) and Black Lives Matter had accidentally planned overlapping events in the public space and not managed to coordinate.

“They weren’t here in 1802,” said Woodland, slightly louder. “I’m an American descended from slavery. We need to make this distinction.” On the mic at that point was the Bangladesh-born leader of MAS, Iman Asad Zaman.

Ellison heard her and came over. What’s going on, he asked her, in hushed tones, assuring her that there was plenty of time for both of the events. He pushed his black face mask up and down as he spoke.

“They need to apologize,” she said. “They don’t understand.” There were tears in her eyes.

“Look, I’m Muslim,” he started.

“I know. I guessed that’s why you are here.”

“I didn’t set this up,” he said, with emphasis.

Ellison moved the discussion away from the capitol steps, huddling with Woodland for several long minutes as he tried to deescalate the situation. He finally seemed to give up and returned to his rug, going through the motions of prayer, bending and kneeling together with the other congregants, and then he made a swift exit as the stage was, finally, turned over to Black Lives Matter.

Notwithstanding this delayed start, these organizers were now old hands, with effective and practiced stump speeches and call-and-response chants. Trahern Crews, a spokesperson for Black Lives Matter Minnesota who has been hyperactive over the last month, led the crowd in chants of “Reparations now!” John Thompson, a repair technician in St. Paul public schools who joined Black Lives Matter after his friend Philando Castile was murdered by Minnesota police in 2016, gave the most rousing speech of the day, dressed in a thick blue suit despite the heat and screaming until sweat covered his face. “I’m angry!” he said.

Advertisement

“It sucks to be a black man in America!” he said, to wild cheers. “If you an ally, you can go home. I need an accomplice!”

Three hours later, the crowd finally dissipated. There would be many more events and Juneteenth celebrations that weekend, all over the Twin Cities. It was a long-awaited moment of release. In the month since George Floyd’s killing, protests and rallies have become so ubiquitous here that there are dozens of interest groups represented in the streets every day. They are not perfectly unified, as the tensions at the Capitol on Juneteenth showed.

Some people wholeheartedly support defunding and abolishing the police, while others, more quietly, think some hope remains in sweeping reform. Distinctions are drawn, sometimes awkwardly, between black descendants of slavery and more recent African immigrants, not to mention other groups such as Native Americans (who are killed by police at the highest rate per capita of any group nationwide). This plurality within the movement is an important dynamic, one that is shaping what effect the unprecedented post-Floyd mobilization will ultimately have on the city of its origin.

“There’s no single MLK figure for the movement today,” said Harry Waters Jr., a black actor and activist who teaches at Macalester College. “Though that’s not a bad thing; in my mind, leadership is something to be shared.” Out of the movement in Minneapolis, several familiar faces have still emerged—for example, lawyer Nekima Levy Armstrong, Crews of Black Lives Matter, and Kandace Montgomery of the Black Visions Collective.

As the overlapping Juneteenth events unfolded on the statehouse lawn, Minnesota lawmakers were concluding a eight-day-long special session inside the Capitol, discussing how exactly to enact the police accountability now demanded by the people. On June 7, the Minneapolis City Council had voted, with a veto-proof majority of nine members, to disband the police department. Shortly after sunrise on Saturday morning (a legislative “day” in Minnesota runs, if necessary, through the night and until 7:00 AM the next day), the House Democrats and Senate Republicans left the building still divided and with no agreement on their hands.

Minnesota happens to be the only state in the country with a legislature split between the two major parties in this way, and prospects for an agreement were never high. “Still, I was very surprised at the amount of resistance that the GOP gave,” said Democratic State Senator Jeff Hayden, whose district includes the neighborhood where George Floyd died. “Fundamentally, it’s in the hands of the Republicans and they really think there is not a problem. They’ve decided to put their heads in the sand, and they’re doubling down, despite the public pressure—they had a very odd press conference this week at which [Republican State] Senator Bill Ingebritsen said that racism is just a ‘sidebar issue.’”

Hayden said he’d been pessimistic going into the session, even though the Floyd case was so explosive. “There are nineteen of us now in the people of color and indigenous caucus,” he told me, out of the 201 legislators across both branches, but “[the Republicans] really don’t want to listen to us. You know, it’s not irrelevant that I could have stopped by the exact store where Floyd died, which is eight blocks from my house, and this exact thing could have happened to me.” And that was a point he made during the session, to little avail.

I asked him whether the Minneapolis City Council could take some things into its own hands given its historic mandate to disband the police department. “So the council has some leverage in deciding what their police department will look like, but there are several things that have to change on the state level to make it really work,” he explained. “Something as simple as the residency requirement [for officers to live within the locality in which they work], how officers are trained and banning certain kinds of training, and arbitration reform are things that cities can’t change. We have to do that. But like I said, we can’t even get them [the Republican caucus] to talk to us.”

Hayden expressed dismay that Republican senators would not embrace meaningful reform even on grounds of fiscal responsibility: police brutality costs taxpayers millions. “We have paid out over $40 million in police misconduct settlements since 2003,” he said, “and I can’t even imagine what the Floyd family’s payout will look like.”

Advertisement

In 2017, the nearby city of St. Anthony, Minneapolis, reached one such settlement with the family of Philando Castile. His mother, Valerie, also attended the hearings last week. “I don’t even know what to call that experience,” she told me, over the phone. “We were just sitting in the gallows [the upper chamber] on Thursday, me and some other folks whose loved ones had been also killed by police. I’m not real sure as to why, other than maybe to give the voters a sense of our hurt, and to say that these things do happen right here.”

She was “not surprised at all” that the session ended in gridlock. “It’s not just this session; since 2016—and this is very, very disappointing—there has been almost nothing that has changed, I mean nothing at all. And from my point of view, the changes the Senate was offering were still very trivial.” The reforms nominally backed by the Republican Senate include banning chokeholds and funding “deescalation” training for police officers, but senators rejected more sweeping proposals from the Democratic House, such as restoring voting rights to felons and putting Attorney General Ellison in charge of prosecuting all police killings. “My days are starting to run together, honestly,” said Castile. “I was tired then, and I’m tired now.”

Philando Castile’s name looms large over the current moment, because he’s a direct predecessor to Floyd as a lightning-rod case of police killing an innocent black man in the Twin Cities. (The name of Jamar Clark, whose death at the hands of police in 2015 led to a huge public outcry, is also prominent.) Castile was shot dead by police, at age thirty-two, at a traffic stop in a St. Paul suburb, in an encounter that his girlfriend, also in the car, filmed on her phone. The subsequent protests led to some light reforms, like bias training for the city’s police. But for those closest to Philando, a certain disillusion set in during the aftermath, when it became obvious that no major reforms were in the cards.

In spite of such an uphill battle, Black Lives Matter has been a transformative influence here, as elsewhere in America. BLM began in 2013 in response to George Zimmerman’s acquittal in the killing of Trayvon Martin, but the movement became a nationwide phenomenon after the 2014 protests in Ferguson, Missouri, against the police killing of Michael Brown. The community of activists that coalesced around BLM has purposely cultivated a sense of endurance in order to cope with the inevitable stops and starts of campaigning simultaneously in a city that is about 19 percent black and a state (of Minnesota) that is only about 3.5 percent so.

“When BLM started up here, it was basically three straight years at a breakneck pace,” said Lena K. Gardner, a prominent Minneapolis activist and ordained minister of mixed black, indigenous, and white heritage. “I was recruited into the movement back in 2015, based on my fundraising and organizing experience, and, basically, the first public protest I planned was at the Mall of America,” she said, giving a sense of how BLM came out of the gate at a clip. “After that, it was just a nonstop whirlwind of rallies and marches. Frankly, I was not prepared to be at that level of leadership that quickly. Everyone got really worn out.”

That was why, in 2017, she helped found the Black Visions Collective, a nonprofit that encourages black activists in the Twin Cities to “turn inward” for well-being and health. “The long haul: that’s certainly been a focus,” she said. Their activities include everything from ensuring that no one’s overworking to organizing “Black Joy Sundays.” Even so, burnout occurred. “Honestly, some people did just leave the movement altogether,” she said. The point is, she said, they were mentally prepared for the next incident that would set in motion a new wave of protest, whenever that would be, and for the long stretch of actions required in response.

Her early engagements with city politicians, including her councilman, Jacob Frey, who is now the city’s beleaguered mayor, were deeply frustrating. “I called it ‘the Wall of No,’” she recalled, of their categorical resistance to reforms. “They were so constrained by ideas of scarcity, of what’s possible, that they failed to realize how bad the police really were,” said Gardner. “So it’s mind-boggling to hear the same city council leaders saying that the things that were ‘impossible’ four years ago are now possible. I’d like to say what we did back then lay the seeds for what’s happening now.”

*

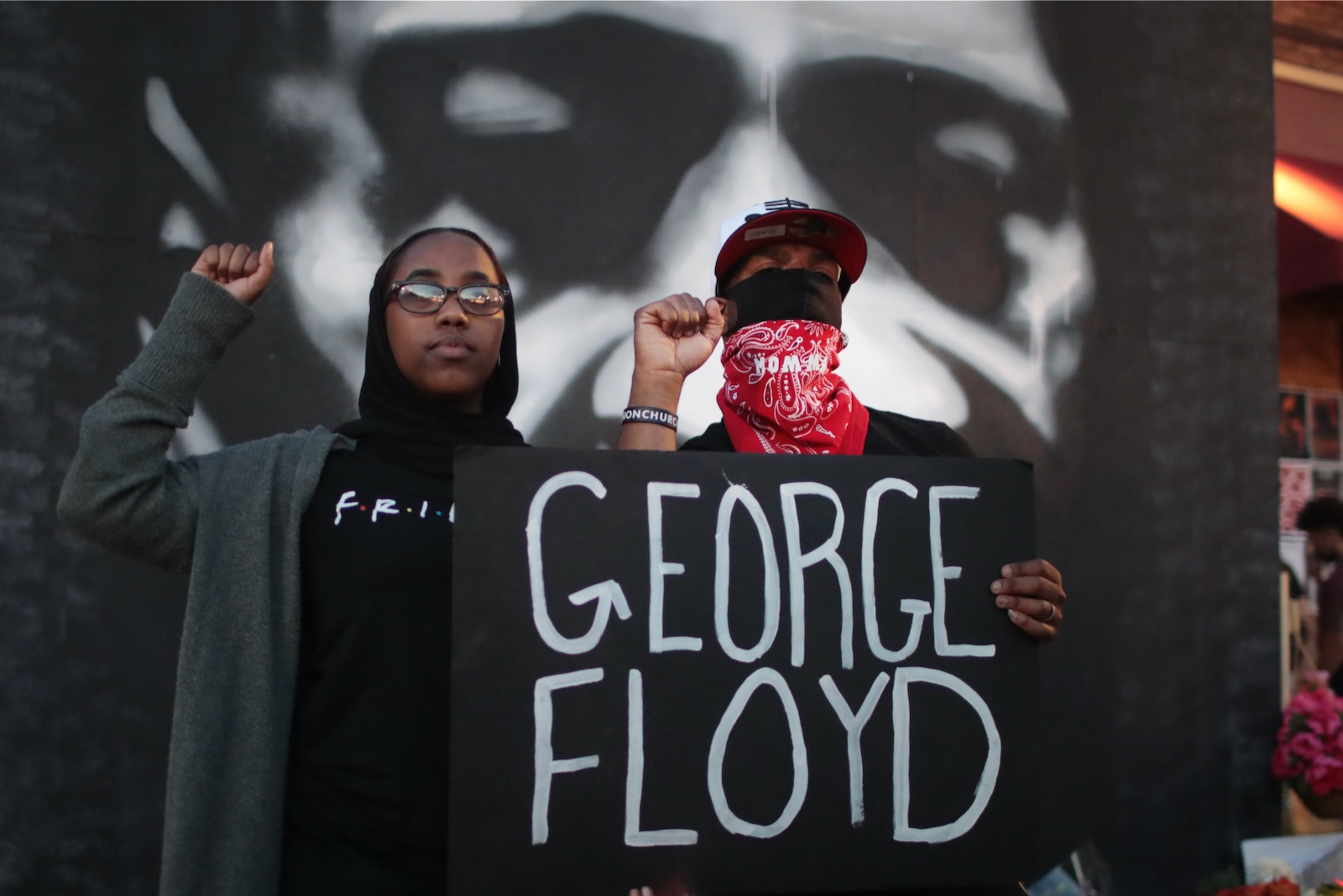

On that Juneteenth afternoon, after the Capitol rally, I went back to Cup Foods, the convenience store at the intersection where Floyd was killed after allegedly trying to use a counterfeit bill. On earlier visits, I’d registered the hand-drawn signs at the entry-point to the site, where traffic is cordoned off, indicating that it had been designated a “sacred space for healing.” The instantly recognizable mural of Floyd’s face set against a sunflower was vivid in the late afternoon light of the days leading up to the summer solstice. There were still hundreds of bouquets of wilting flowers, and families and dogs, many distinct little groups of twentysomethings having a “day out,” a yurt transplanted from Standing Rock in North Dakota, a capoeira troupe, a revivalist preacher speaking about Gethsemane over swelling orchestral music, and several barbecue stalls with long lines.

Kia Bible, a mother of two who lives nearby, had borrowed her uncle’s white bus, parked it near the memorial three weeks ago, and assembled an ad hoc team of twenty-four-hour volunteer medics. A defining aspect of the rolling protests is the miraculous feeling of being provided for, as it became clear that citizens were stepping up to furnish things that the government never even tried to supply: free masks, free food, clean water, first aid. Beyond Cup Foods, murals and paintings commemorating Floyd are everywhere in the city, which has become an open-air memorial to him.

On East Lake Street, a major site of looting early on in the protests, businesses were still boarded up with hand-painted or printed signs saying things like “FAMILIES LIVE HERE!” (on an apartment building) or “We are a family-owned business, please don’t tear us down” (on Saigon Garage). The violent phase of the protests lasted only for about a week. After the National Guard came and left, and after several early symbolic victories were won—the arrest of officer Derek Chauvin, the City Council’s astonishing vote to defund the police, and the school district and University of Minnesota’s decisions to sever ties with the police department—the protests changed in temperature and temperament. By the time I arrived in Minneapolis, nearly a fortnight after Floyd was killed, the daily demonstrations were blurring together into a huge, rolling civic action.

“The momentum of those early days is not gone, but it has shifted, from an uprising in the street to a search for alternative infrastructure to keep people safe,” said Charmaine Chua, a member of the Abolition Collective and longtime Minneapolis-based organizer. Although she was living in Southern California when Floyd was killed, she returned to the Twin Cities once the force of the protests became clear, in late May, to help strategize the release of arrested protesters.

“These [protesters] have been getting whiter and younger,” said Cheryl Persigehl, a volunteer with the Racial Justice Network, who wore a yellow vest and acted as a crowd-control marshal at a large rally on Saturday, June 13, outside the Hennepin County Government Center, downtown. This was just one day after another enormous protest of thousands of people outside the Minneapolis Police Federation that was calling for Lt. Bob Kroll to resign as police union president. Persigehl came to the Network through the 2017 mayoral candidacy of lawyer and racial justice activist Nekima Levy Armstrong. Though she is more popular than ever today, Levy-Armstrong lost that race. But her run bequeathed the legacy of a vast army of volunteers who have mobilized for various causes in the three years since.

“We have a very active text group, and we quickly pivoted from providing food security for vulnerable people during the Covid-19 lockdown into ground support for these protests,” said Persigehl, who had been on the streets at that point for fifteen consecutive days. (That was also a significant milestone because of the incubation period of the disease: remarkably, there seems to have been no major coronavirus spike in Minneapolis despite the size and density of the protests. The wide distribution of free masks and hand-sanitizer has surely been a factor.)

Levy Armstrong, a law professor who became prominent in Black Lives Matter after joining the Ferguson protests in 2014, is widely acknowledged as one of the people who has built up the protest muscle memory here over the last six years. She has been on the frontlines of organizing after headline-making incidents like Jamar Clark’s killing in 2015. When I saw her speak at the Government Center rally, confident and with her long hair down, she opened with an emphatic: “Fuck the police.”

Many of the white people who are making up an increasingly large fraction of these protests moved to Minneapolis years earlier in part because of its liberal, progressive reputation. “There’s this whole idea of Minnesota exceptionalism,” Gardner told me. But that reputation—for being diverse, welcoming to migrants and refugees, politically purple—has lost its shine. According to a 2015 report from the University of Minnesota Law School, the Twin Cities’ historic commitment to civil rights has been eroding ever since the 1980s as Reagan-era policies like school choice took hold, reversing decades of greater integration. Today, as State Senator Hayden put it, “You’ll find that white people do very well here… but we have been leading the country in terms of health and wealth gaps between white and black people.”

Mary Everett, a retired, white legal aid lawyer I met at the Government Center rally, told me she had grown up in rural Indiana with KKK-affiliated grandparents and moved to Minneapolis the first chance she got. “It sure seemed like that when I first moved here in the Seventies,” she said. “But it’s clearly not the place that we think it is.” After a couple of weeks of staying at home out of coronavirus concerns, she finally decided to come out for this protest.

Minnesota’s governor still has a mandate to call another special session of the legislature to reopen the debate about police accountability, but where the two chambers left off last week was not a promising place to restart. By that Juneteenth Friday afternoon, well before that legislative day was out, “the parties weren’t even meeting,” said Minnesota House Speaker Melissa Hortman.

Some of the people who have now devoted much of the last few years to the protest movement are turning to other avenues, including electoral politics. John Thompson, the friend of Philando Castile’s I heard at the rally outside the Capitol, is now running for the Minnesota House to represent District 67A in St. Paul.

“It sucks to be a black man in Minneapolis,” he told me again, when we met in a coffee shop in his district, a few days after Juneteenth. “People tell me, You can’t say stuff like that if you’re running for office. But that’s the problem!” Thompson is widely considered the frontrunner and his endorsements include one from Keith Ellison. He hopes to enact a new theory of change, taking aim at the legislature—so clearly a roadblock to people’s demand for reform for these many years.

“People think that building is a museum,” he said, of the Capitol. “Instead of what it is: an office.”

This report, the first in a series of three, was supported by the Economic Hardship Reporting Project.