An artist is a person who invents an artist. So it has been said, neither by Marcel Duchamp nor by Jorge Luis Borges, but by Harold Rosenberg, the critic who invented a school of painting when he coined the term “action art.”

The American photographer Stephen Berkman could be said to have taken Rosenberg literally. Two decades in the making, Berkman’s huge new book, Predicting the Past: Zohar Studios the Lost Years invents, creates, and explicates an artistic oeuvre—in this case, one that purportedly belonging to a nineteenth-century studio photographer named Shimmel Zohar. (The name suggests a pseudonym: while “Shimmel” is the Yiddish diminutive for Simon, it also evokes the German word for “mold.” “Zohar,” meaning “radiance” in Hebrew, is the name given a foundational text of Jewish mysticism and a key element of Kabbalah.)

Berkman is hardly the first artist to invent another. In 1998, William Boyd, in collaboration with David Bowie, conjured a dead American painter and published a spoof biography. With his 2015 graphic novel, The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye, Sonny Liew created an unsung comic book artist and used his fictional oeuvre to recount and critique his native Singapore’s contested history. Perhaps the most elaborately invented artist is the subject of Max Aub’s Jusep Torres Campalans. First published in 1958, in Mexico, where Aub (a refuge from fascist Spain who escaped occupied France for Mexico in 1942), Jusep Torres Campalans is a novel in the form of a monograph typical of the Swiss art book publisher Skira—a fabricated biography augmented with critical articles and texts, as well as copious illustrations, providing a career analysis of an unknown Cubist painter and political anarchist, a compatriot and, as shown in a doctored photograph, an associate of Picasso. The simulation extended to a Torres Campalans exhibition in a New York gallery when the English translation of Aub’s novel was published in early 1962—the work, of course, was provided by Aub, hitherto known only as a writer.

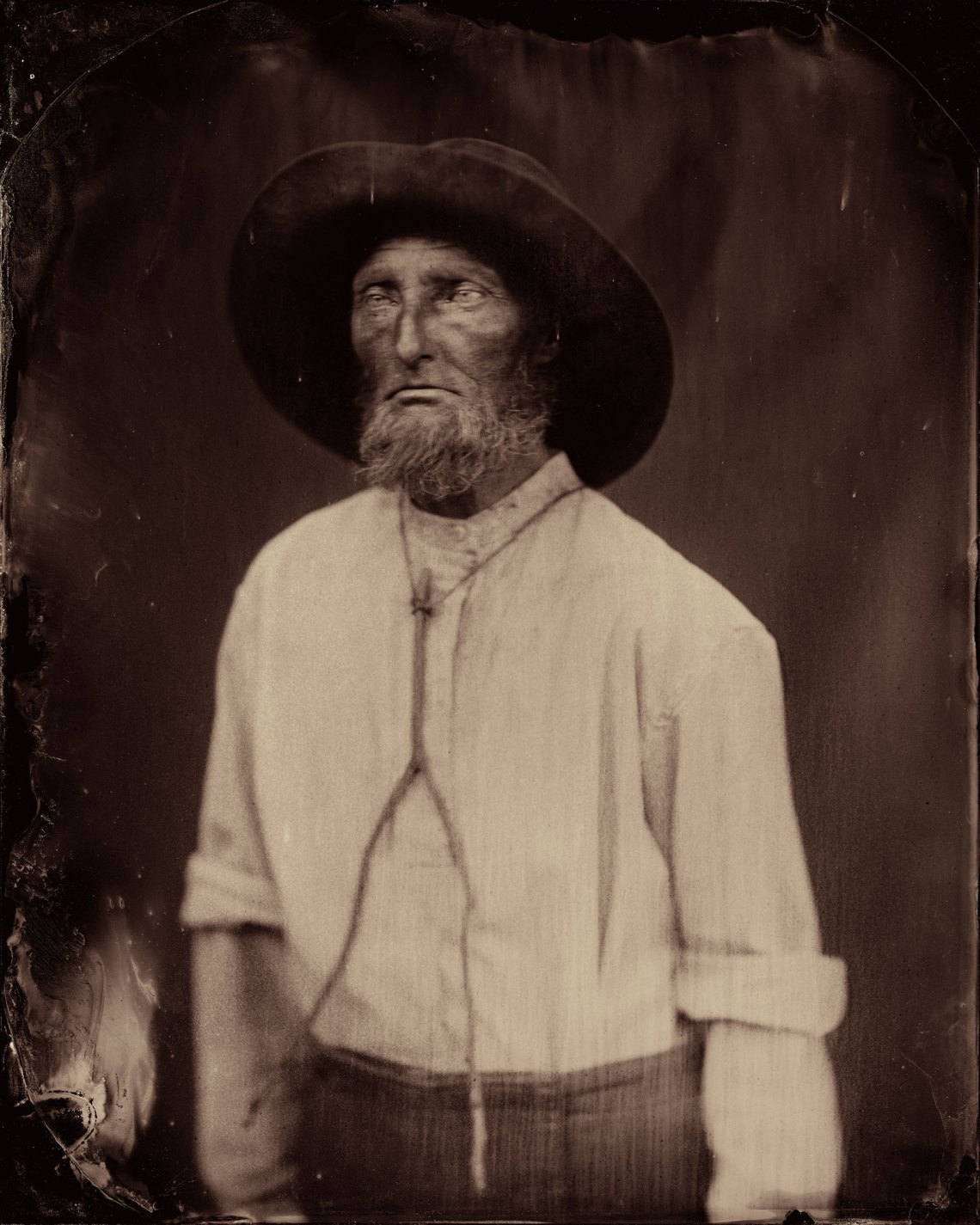

Berkman, however, does have a reputation as an artist. He is part of the “antiquarian avant-garde,” a movement so named by the critic Lyle Rexer to describe those photographers who, around the time that mechanical cameras and chemical darkrooms were being superseded by digital image-making in the 1980s and 1990s, revived the long discarded, labor-intensive photographic technologies of the nineteenth century. Some made use of pinhole cameras, others worked with stereopticon images. More than a few produced daguerrotypes or tintypes. (The best known of these “alternative process” photographers is Joel Peter-Witkin, noted for making silver prints of staged tableaux, often of transgressive scenes.)

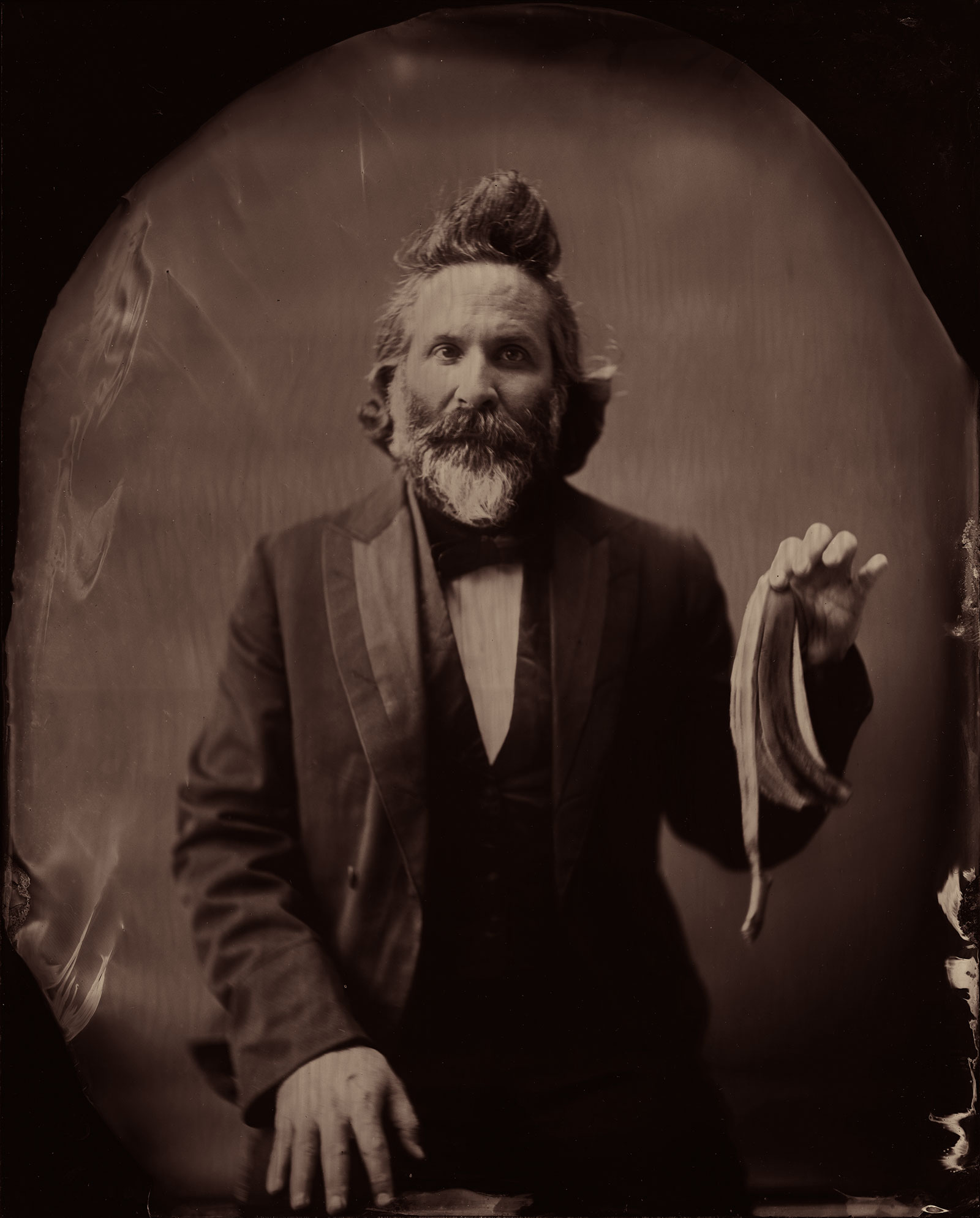

Berkman’s own particular photographic technique is the wet-collodion process, which, similar to daguerreotypy but more complicated, involves coating a glass plate with a combination of ether, grain alcohol, and nitrate cellulose, then dipping the plate in silver nitrate and exposing it while still wet. Antiquity is further simulated by Berkman’s use of a view camera, vintages lenses, and prolonged exposure times.

According to Berkman’s introductory narrative, Shimmel Zohar immigrated to New York City from Lithuania in the mid-nineteenth century and briefly established a photography studio on the Lower East Side before vanishing from history—leaving, aside from his photographs, only a fragmentary journal written in Yiddish. But, if the artist is invented, his photographs are not; rather, in their execution, as well as their look, Zohar’s images could have been produced 150 years ago. (In this, Predicting the Past resembles the performance artist Eleanor Antin’s 1992 silent film The Man without a World, which purports to be and, in terms of its subject and film language, could have been, a rediscovered Yiddish movie from the late 1920s.)

Some of Berkman’s fakes simulate authenticity with meticulous accuracy. “Illusionist with Circassian Spirit” adroitly fabricates the sort of fraudulent spiritual photograph created by Zohar’s contemporary, William H. Mumler. On the other hand, no Victorian photographer would have been likely to create the image of a woman wearing a black dress festooned with cameo portraits, posed against a painted backdrop and standing next to a banner emblazoned Zohar Studios atop a pair of wooden roller skates. (Close examination reveals the presence of a miniature winged camera set as a decorative peineta in her hair.)

Berkman is so skilled a craftsman that one can only speculate how certain of Zohar’s images were produced. A few could be relatively straightforward photomontages. Latent Memory appears to be a vintage image of a solemn child that has been modified so that she holds a rag doll in one hand and, in her other, a furry paw extended from off-camera ape. Man with Downtrodden Banana and Woman Hand-Knitting a Condom are similar visual gags. (The latter also demonstrates the subtle blurring achieved by a lengthy exposure.) Some, like Taxidermied Taxidermist, in which a stolid craftsman poses amid the stuffed birds and small animals in his workshop, might be reproductions of found vintage portraits that Berkman transforms only by giving them playful titles; A Luddite Gazing into the Future is another such.

Advertisement

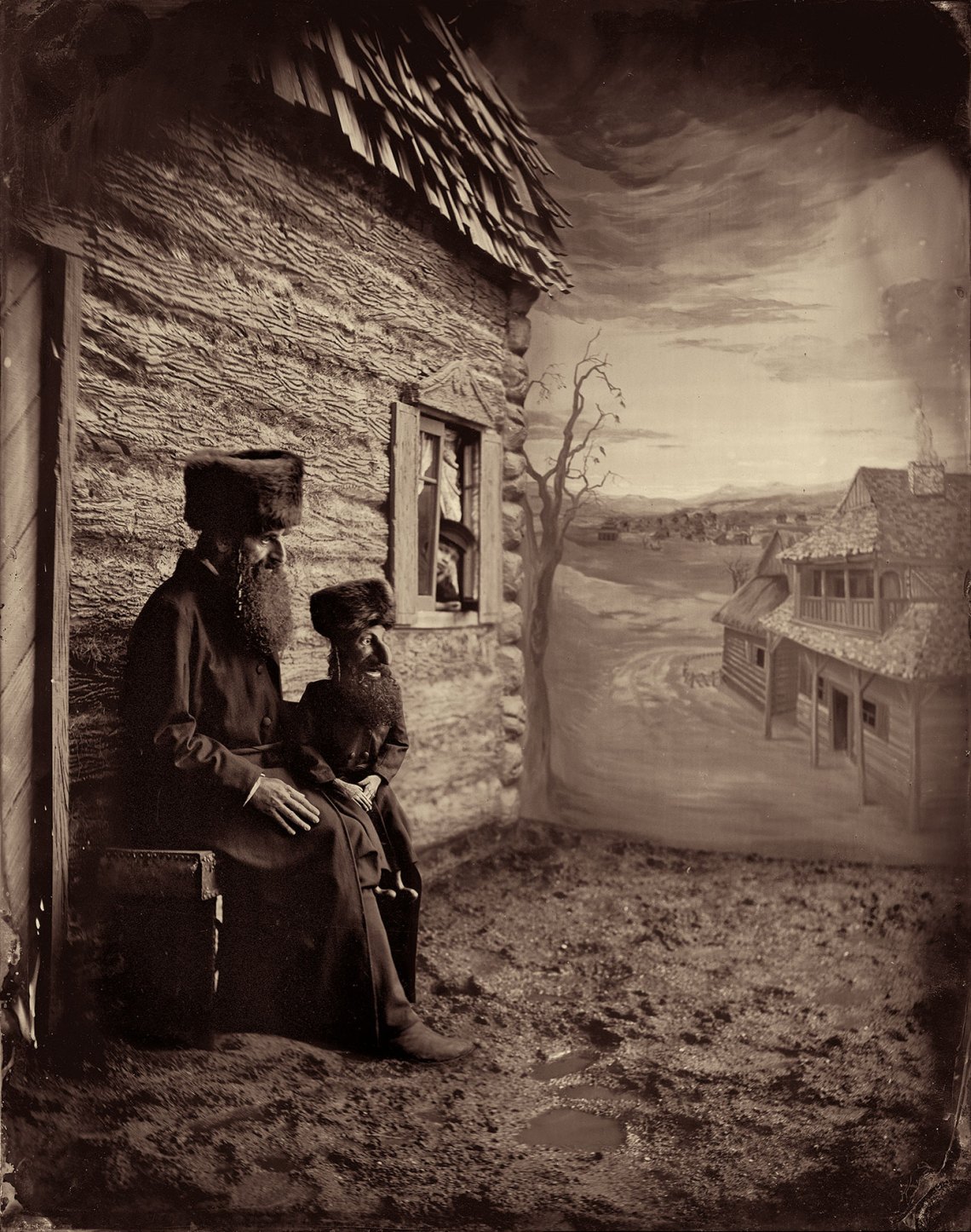

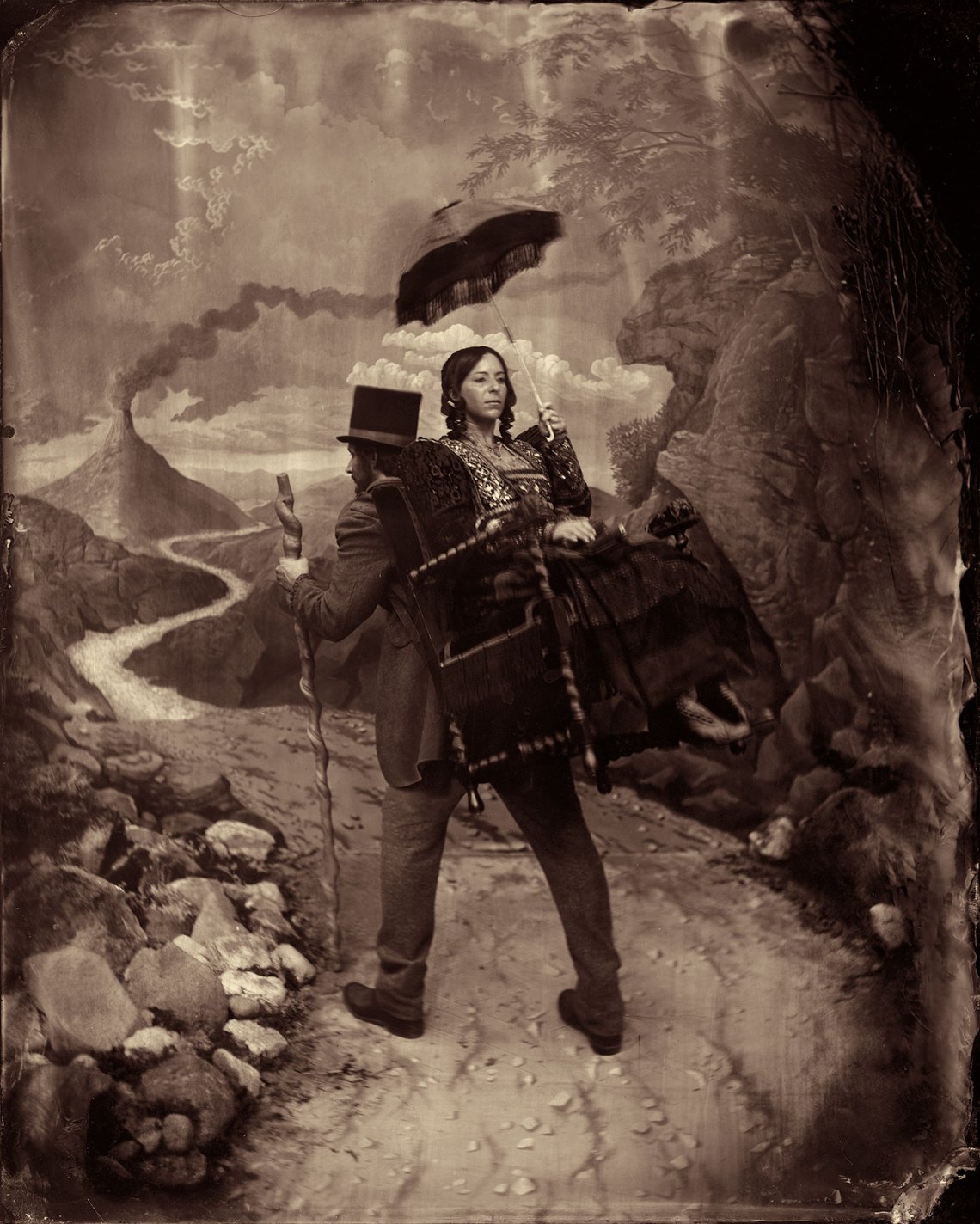

Most of the images, however, are clearly contrived. Berkman’s Zohar has an apparent fondness for riffing on certain tropes about Jewish life. A Wandering Jewess, based on an anonymous nineteenth-century French print of Le Juif Errant, literally saddles the subject with a well-dressed woman in a sedan chair and adds a backdrop dominated by a smoldering volcano. Shtetl Shtick poses an elderly Hasidic man outside a rustic dwelling with a ventriloquist dummy. Portrait of a Blind Mohel is another possible collage, placing an elderly observant Jew next to a box of implements set on a table covered by a cloth embroidered with a Hebrew quote from the Book of Ezekiel in which the prophet compares the Jewish people to an abandoned infant: “With your blood, live.”

There are also ironic allegories. The Songbird and the Sharpshooter suggests a mash-up of a “Douanier” Rousseau painting and a Matthew Brady Civil War portrait, in which the uniformed sniper not only has a typical nineteenth-century mustache and beard but a majestic crown of dreadlocks as well. (The same jungle set appears in Zohar’s portrait of a pseudo-scientist, Itinerant Phrenologist, and in another image that refers to the nineteenth-century German naturalist’s discovery of a lost language, Humboldt’s Parrot.)

The photographs are followed by over 200 pages of notes and appendices. Each image is given a detailed, deadpan exegesis, thoroughly footnoted and repleat with an inextricable blend of real and invented scholarship. To take one example, Berkman quotes my own history of Yiddish cinema, Bridge of Light, in the service of an invented Western, a silent film with the Yiddish title Belve Der Yid—a play on “Billy the Kid.” In other cases, the information is real: the annotation for the photograph Plate Box serves to explain the complex collodion process that Berkman employs to produce his images with legitimate material on the evolution of portrait photography in nineteenth-century New York.

While this lengthy appendix (which includes a slyly solemn afterword by Lawrence Weschler, whose books include one on Renaissance “wonder cabinets” and the contemporary Museum of Jurassic Technology) is engaged in the high-spirited postmodernism of Nabokov’s Pale Fire or Roberto Bolaño’s Nazi Literature in the Americas, Berkman takes the genre a good deal further. The annotations are profusely illustrated with expertly forged handbills, sheet music, trade cards, ledgers, receipts, advertisements (including one for an “automatronic spirit-rapping hand” that is “proficient in telegraphese”), illustrational prints, diary pages, and additional photographs in addition to images of wax cylinders, souvenir fans, promotional thaumatropes, paintings, and a few frames of a lost films.

Like a matryoshka doll, jokes are nested within jokes. Berkman maintains that a made-up newspaper, American Luddite, was entirely hand-drawn to resemble letterpress print and, reproducing a front page, also includes a detail in which this is evidently so. As Aub’s postmodern novel serves to question both the development of modern art and the possibility of writing a biography, so Berkman’s entire enterprise is underscored by the notion that, rather than provide evidence or document the present, photography is a technology with which one might fabricate history or advance alternative facts.

Predicting the Past is the catalogue for an exhibition at the Contemporary Jewish Museum in San Francisco that, thanks to the pandemic, only exists in virtual form on the museum’s website for now. This is both unfortunate and an unexpected validation of the quote from the pioneering chemist Humphry Davy, which Berkman uses as an epigram for his book: “The future is composed merely of images of the past.” The notion of a virtual art show might have been invented for Berkman’s invented artist and his imaginary yesteryear.

Predicting the Past—Zohar Studios: The Lost Years is published by Hat & Beard Press.