In this year of unprecedented upheaval, ongoing closures due to the pandemic had already forced many cultural organizations to leave behind the status quo when the Black Lives Matter protests began. Reckoning with systemic white supremacy, most have foregone persistent, structural change for a quicker, more visible counterpart: representation. Just over a week after George Floyd’s death, the Criterion Channel, the streaming service of the distributor Criterion Collection, released free of charge for a period (now over) a program of independent films called “Black Lives.”

Most of the films by Black directors in the online program are not actually part of the Criterion Collection catalogue, which is acutely dominated by works by white directors. Neither is Portrait of Jason, the only film on the list by a white, female filmmaker, Shirley Clarke, who was born a century ago last year. In 2020, her name is not well known. She never experienced mainstream or commercial success, and her contributions to the underground film world are often just a mention in prominent scholarship about American avant-garde cinema. Her films fell out of distribution until Milestone Films made a recent, concerted effort to restore and redistribute them, which has led to their presence in arthouse cinema programs to do with race, queerness, and female filmmakers.

Clarke’s oeuvre provides a hybrid of approaches that emerged in filmmaking in the 1960s—experimental, documentary, and narrative—and she undertook to expand the reach and accessibility of the form. In 1960, she, Louis Brigante, and her former classmate Jonas Mekas founded the Film-Makers’ Distribution Center, an artist-run group that would market independent films to commercial theaters so they could compete with Hollywood productions. She was a member of The Group, a collective of independent producers, actors, directors, and theater managers who wrote the manifesto “Statement for a New American Cinema,” which was published in Film Culture magazine in 1961 and ended with the lines “We are for art, but not at the expense of life. We don’t want false, polished, slick films—we prefer them rough, unpolished, but alive; we don’t want rosy films—we want them the color of blood.”

Three of Clarke’s feature films The Connection (1961), The Cool World (1963), and Portrait of Jason (1967) could be taken as a trilogy on Black subjects and white documentarians. The formal concept of Portrait of Jason is experimental for its striking simplicity: 105 minutes edited from footage captured by a single camera, set on one subject, Jason Holliday, a Black, gay performer and sex worker (self-identified “house boy” and “hustler”) in Clarke’s Hotel Chelsea apartment. This setting is complicated by the endurance test of the shoot itself, a marathon twelve hours long, and by the line of questioning, which is retained in the final edit. Clarke and her partner, Carl Lee, an actor and frequent collaborator of Clarke’s, ask Holliday to tell stories of his life in a manner that becomes increasingly aggressive as Holliday gets more and more intoxicated. The result is not a portrait, but a dialogue, and Holliday’s responses alternate with bewildering speed between vulnerable confession through tears—crocodile and real—and melodramatic soliloquy through laughter–hysterical and vindictive.

When at a pivotal moment in the film Lee, who is Black, accuses Holliday of “selling Black soul to white people,” Holliday’s answer speaks to the conflict between authenticity and performance for a Black man in a white world. “Ain’t I?” Holliday snaps back, his eyelids heavy, “And they’re buying like mothers. But you got to be cool. You can’t overdo it, because they’re like any other sucker, they’ll keep coming back for more as long as they don’t feel that they’ve been royally fucked. They’re gluttons for punishment. And you’ve got to be hip enough to be able to constantly feed just the necessity to this hunger.” Then, in a singsongy voice, he asks Clarke a question he repeats throughout filming, “How am I doing?”

In a 1970 interview, Clarke laments her limited audience. “Most of the time, it’s already the people who agree with me, which is rather unfortunate.” She laughs. The interviewer interjects that Portrait of Jason should be shown on television, and Clarke agrees, but with a shrug: “I knew perfectly well when I made the film that only those people with a great understanding would really understand this film.”

She immediately reconsiders, and asks:

Is it inverted snobbism of some kind on my part, or some sort of a dishonesty in approach? Because it is some contradiction to saying that you want to do a film that will be helpful to a situation, such as the Black and white problem in the United States, and certainly [The] Connection, [The] Cool World, and [Portrait of] Jason dealt very much with this problem, and I feel myself it is the great problem of our time, the race–or—racism everywhere, not only in the United States, but if I believe this to be true, how come I’ve done a film that has limited who it’s going to be seen by?

The interviewer asks if she can answer her own question. She blurts out in frustration, “I’m dishonest about it in some way!”

Advertisement

Clarke grew up in New York City, the eldest daughter in a wealthy family that lived on Park Avenue. According to Lauren Rabinovitz, who published perhaps the most extensive biography of Clarke (a chapter’s length), she only began making films when her psychoanalyst recommended it to her as a hobby to relieve her malaise after she had become, instead of a professional dancer as she had dreamed, a suburban mother. She had previously studied with Martha Graham, Hanya Holm, and Doris Humphrey, and this expertise led to her earliest films’ focus on dancers.

She enrolled in the City College of New York, then the city’s only film school, and studied with the German painter and avant-garde filmmaker Hans Richter. After submitting her work to international film festivals, she won prizes and rapidly gained the attention of the documentary filmmaker Willard Van Dyke, who invited her to work with him, Richard Leacock, and D.A. Pennebaker on short films about American life for the United States pavilion at the 1958 Brussels World’s Fair. After a series of documentary projects and experiments with the medium, her first feature film, The Connection, premiered at Cannes in 1961.

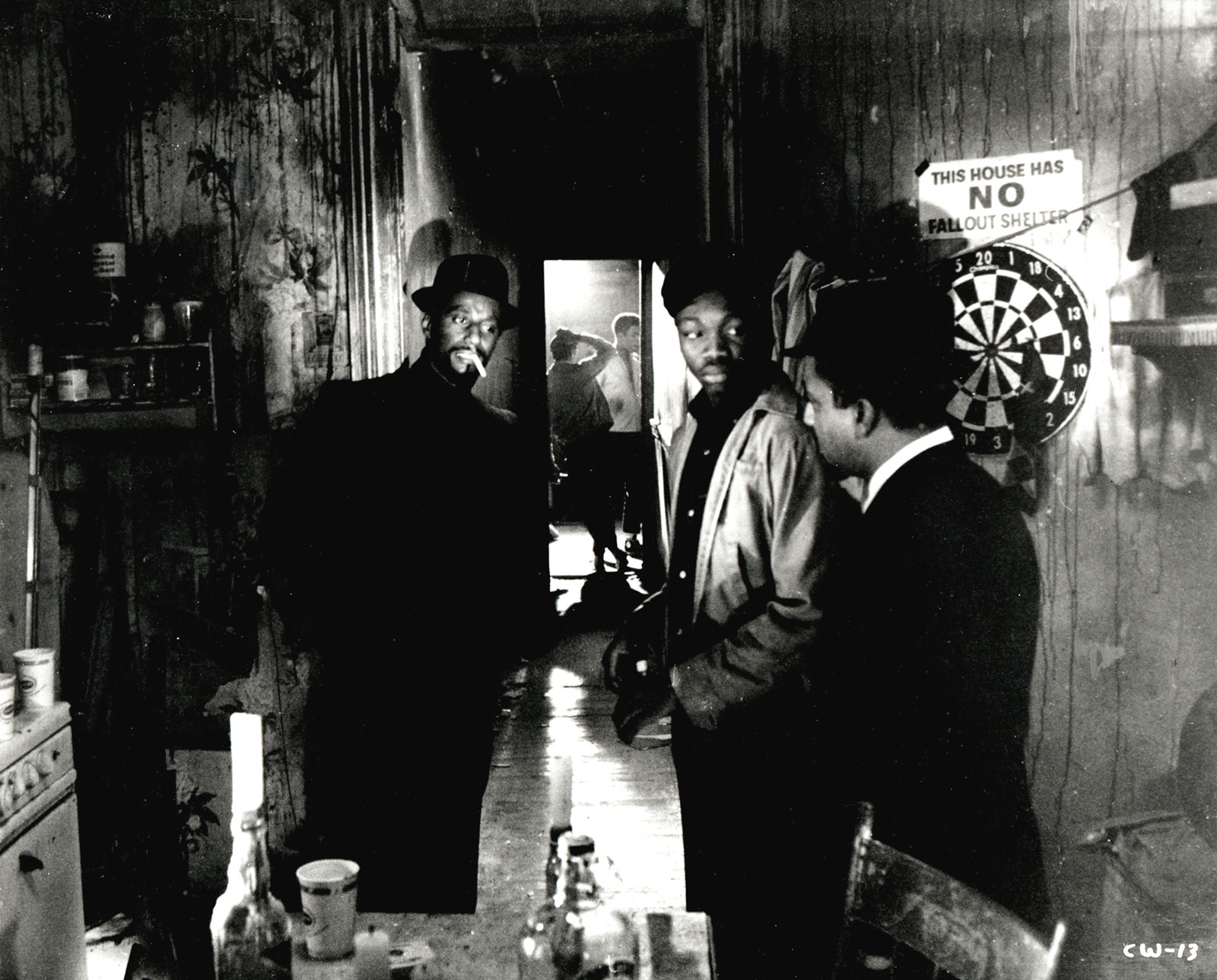

The Connection, which was promptly banned in the United States for obscenity, was an adaptation of Jack Gelber’s play about jazz musicians waiting around for their heroin dealer in a loft apartment. Markedly influenced by the Beat Generation, Clarke made the story swing—and not just through the music, which was performed on-screen by Freddie Redd and Jackie McLean, playing themselves, but also with the camera, which roves wildly around the loft. The conceit of the film is that it is a recovery project revealing never-before-seen, unedited footage from an unfinished documentary by a fictional director named Jim Dunn (played by William Redfield).

The result is a scripted satire of cinema verité that conveys the moral vanity of white documentary filmmakers, as Dunn unwittingly becomes a subject in his own movie. Between takes, the cameraman, J.J. Burden (Roscoe Browne), keeps rolling while Dunn barks orders at him and begs the addicts to cooperate (“act naturally!”). It gradually becomes clear that Dunn has arranged a fix for his subjects in exchange for their participation, and his manipulation of the “authentic” scenes he claims to document breaks the fourth wall and the hallowed ethics of documentary.

Clarke’s project was to investigate themes of exploitation and complicity in filmmaking. In The Connection, McLean approaches the camera and chides Burden, “Hey, J.J., you sure have changed since Harlem, man.” Burden retorts, “So have you, Jackie.” “I’m my own man,” McLean slings back. “Is your name going to be on this film?” A pivotal power dynamic is revealed in this revelation of personal history: Burden is from Harlem. His connections are likely the way Dunn got access to the musicians in the first place. But when Dunn realizes Burden has caught on camera his invasive direction between takes, he furiously threatens Burden, shouting and stuttering, “I’ve given you a real break…. Anybody would be ecstatic to work with me on this and take my direction…. Just remember, I can always get another cameraman!” The camera still rolls, recording not the jazz musicians but the white auteur threatening his Black worker, while the musicians snicker at the scene from upstage.

This revealing moment is not unlike an overtly aggressive scene in Portrait of Jason, which occurs in blackness. Clarke included the recording that continued on the audio track while the camera was being loaded with film, so the viewer sits in darkness and listens to Lee hurl insults at Holliday, calling him selfish, a “great actress” and a “con artist” who hasn’t said anything different from “any other faggot I could go down in the street and find to say the same goddamn thing.” Holliday’s demeanor turns disdainful, but he thinly masks it with bored resignation. “But he wasn’t given the opportunity,” he sighs, “and I should be grateful,” pulling on this last word with bitterness. “There’s only one role you can do, Jason, and that’s you,” Lee scolds him. Clarke and Lee are suddenly recast as manipulative and patronizing, virtually holding Holliday hostage in the name of “truth.”

Advertisement

Four years earlier, the same year Clarke left her husband (she had fallen in love with Lee on the set of The Connection) and life in the suburbs, she made The Cool World, another feature that blends documentary and narrative. The cast was made up of Black non-actors from Brooklyn and the Bronx who play teenage gang members; on location in Harlem, Clarke’s crew used DIY techniques—the cinematographer handheld the heavy 35mm camera and Clarke devised a kind of proto-Steadicam, cleverly using a clothesline to stabilize and dolly the camera. The film was another adaptation, this time from a book by Warren Miller, which James Baldwin called “one of the finest novels about Harlem that has ever come my way,” and Dizzy Gillespie wrote the original score.

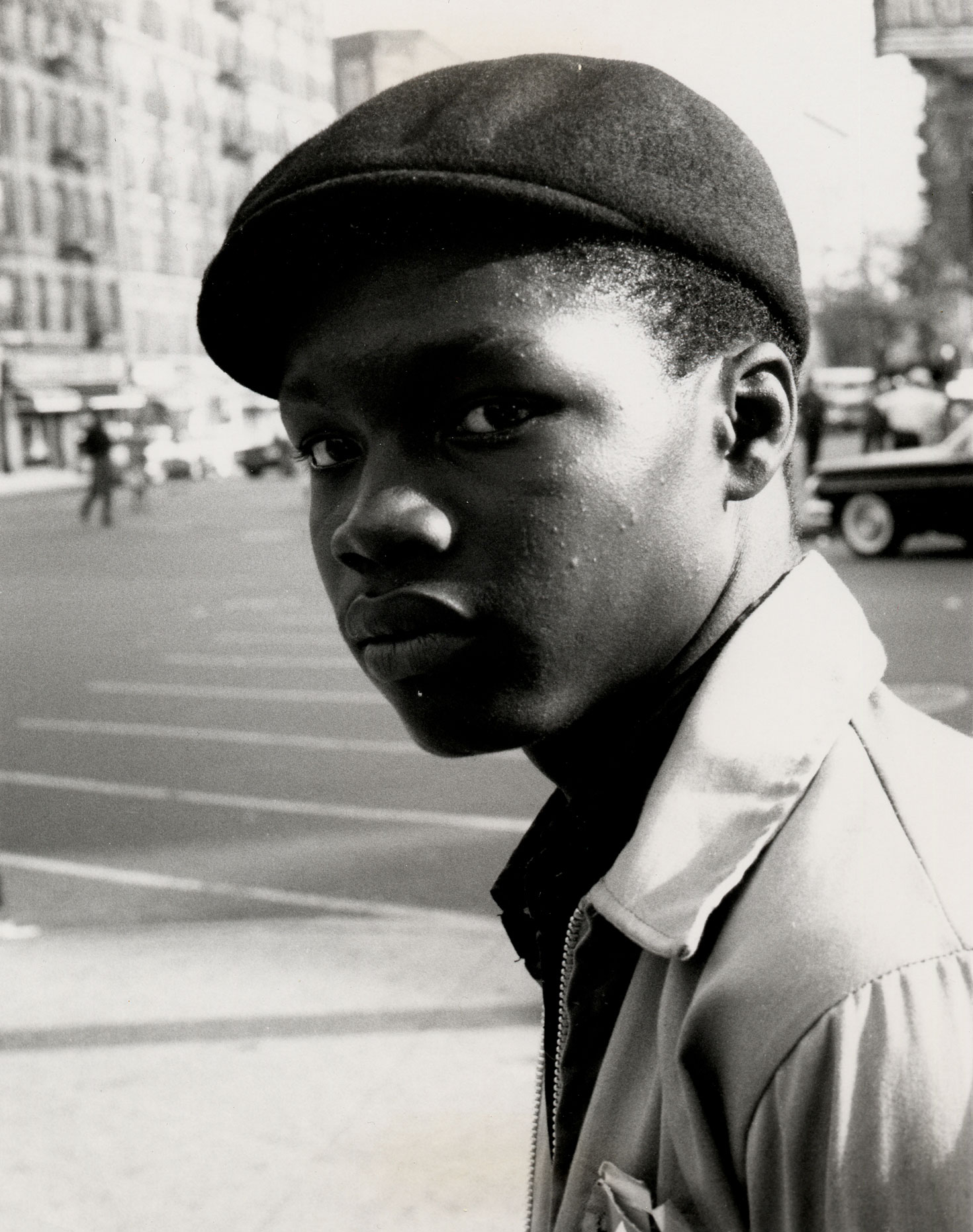

Throughout The Cool World, scenes of early-Sixties Harlem interrupt the script. Nowhere is this more potent than in the opening scene: in black and white, the impassioned face of a Black nationalist preacher fills the screen. He looks into the camera and shouts at the top of his lungs: “Do you want to know the truth about the white man? The white man is the devil! The Black man is the original man!” The camera zooms out slowly, revealing his place above a few listeners nodding below. The speech continues for two minutes as staccato shots cut between glimpses of Black passersby and the white cops who watch them smugly. The preacher yells, “The truth is that the white devil, who after one hundred years of so-called freedom, is still persecuting, beating, jailing, and killing our brothers…. We should rejoice, rejoice together, for the time we are living in is a time for reclaiming our own!”

The camera captures everyday life on the street—a man reading a newspaper, a young girl laughing inside the protection of her mother’s arms, men deep in thought, smoking cigarettes—but the sequence also makes clear that the film crew is trespassing, because in almost every shot, those being filmed notice the camera and look directly into it—bashfully, suspiciously, or with a glare. “Join with me in reclaiming what is rightfully ours,” the preacher shouts. “Let the devil, the white man devil, hear you!” But his words fade out as we see a teenage boy call to his friend. He does not look at the camera, because he is an actor. We have just met the film’s main character, Duke, a representative of all those for whom the preacher’s speech can’t compete with daily survival.

Rabinovitz has written about the tension between intention and reception in the marketing of The Cool World, which played at the Venice Film Festival in 1963, and, when released in the United States, screened only at arthouse cinemas catering largely to middle-class white audiences. Clarke was interested in getting showings at the theaters frequented by Harlem teenagers, but all attempts failed. She was portrayed in the press as a courageous auteur for choosing to work with Black non-actors and crew members, and the documentary scenes were characterized as a rare glimpse at the reality of the ghetto. In this way, The Cool World became the very thing Clarke critiqued in The Connection.

Clarke damned the director in The Connection for his moral arrogance and manipulation, undergirded by the pride of subversion (“I’ve told you,” he sputters, “I’m not interested in making a Hollywood picture!”) Portrait of Jason is avant-garde in that Clarke offers no proxy for the exploitative filmmaker, but the enduring question, given the mistakes of the The Cool World and her later concerns about “dishonesty,” is whether Clarke was intentionally damning herself.

In recent years, feminist critics and programmers have attempted to rectify Clarke’s omission from the avant-garde and independent canon. They place emphasis on her pioneering role as a rare female auteur, and Clarke is most often quoted on the oppression women faced in her field and time. Though this exclusion became her cause, one which envisioned the Film-Makers’ Distribution Center and the support, infrastructure, and audience for an independent cinema that exist today, she never enjoyed the benefits herself.

Why, then, did she choose to film these three stories of Black men? In a 1985 interview with DeeDee Halleck at Clarke’s home in the Hotel Chelsea, Clarke reflected on her career and explained, “I identified with Black people because I couldn’t deal with the woman question and I transposed it. I could understand very easily the Black problems, and I somehow equated them to how I felt. When I did The Connection, which was about junkies, I knew nothing about junk and cared less. It was a symbol—people who are on the outside. I always felt alone, and on the outside of the culture that I was in. I grew up in a time when women weren’t running things.”

Four years before that interview, the critic bell hooks explored the blind spot prevalent then, and still today, in white feminism, in her book Ain’t I A Woman?. It ignored not only the very existence of Black women, hooks wrote, but “It was further assumed that identifying oneself as oppressed freed one from being an oppressor.” When Clarke’s interviewer in 1970 asks, “What does Jason represent?” she replies, “What has happened to Jason, and what has made Jason who he is, is definitely the fault of American white society, and what interests me so much in the film is that Jason—without ever once saying this–you can’t leave that film and not be aware of what has been done to him.” With both this statement and the claim to understand Black oppression based on personal feelings, Clarke—whatever her intentions—places herself outside of, and disassociated from, systemic racism.

Clarke is capable of cynical, realist, and nuanced examination of the problem of racist power dynamics, but she burdens her Black subjects with hopelessness—the heroin stupor of The Connection; violent capture by white police in The Cool World; begging with the interviewer in Portrait of Jason. In his 1989 book Allegories of Cinema, David E. James placed The Cool World in the category of independent films he characterized as unable to imagine structural change. “They strain the industry’s narrative and representational codes,” he writes, “but they cannot pass beyond them any more than they can conceive of alternatives to humanist appeals on behalf of the social plight of the Black people they present as sensitive and courageous but essentially impotent and condemned.” Although these films were in step with the civil rights reforms of their day, James writes, “riots in Los Angeles, New York, and Newark and the assassination of Malcolm X revealed a social urgency they could not address.”

Such a critique is also reliant on the idea that films can forge social change. Artist and filmmaker Blair McClendon wrote recently of the misplaced importance given to “storytelling” during an uprising. If we are to address white supremacy, he writes, “We must stop asking what our stories can do. The artist rarely outpaces the people in the streets. We can honor the tremendous risk they have taken on and we can do so by trying to make work that speaks as clearly and honestly about power as the internal movements of our psyches.”

A year after her centennial, we might see that Clarke was most prescient when she saw herself as part of a system she wanted to destroy, rather than when she disengaged from it. The manifesto she signed in 1960 does not call for reform; it describes “blowing up” the entire system of financing and distribution that limits the types of films made and by whom. Clarke in particular resolved to do this by creating the Film-Makers’ Distribution Center. Soon after that vision buckled under overwhelming debt, experimental film found shelter in universities and museums, having failed to force its way into commercial spaces and in front of wide audiences, as Clarke had hoped.

This survival tactic sequestered alternative cinema behind new economic barriers and debilitated its accessibility, solidifying the institutional racism still rampant in not just the commercial but the academic film industries. Partly because of this, canons are sculpted by inequity, one example being Criterion Collection, which in its haste to make change mistook Clarke’s films as being about “Black Lives” when they’re really about how white power operates. Not long after the Film-Makers’ Distribution Center’s collapse in 1970, Clarke found out that Mekas was establishing a “museum of experimental film,” the Anthology Film Archives, and that her films were not included in its new canon of avant-garde film, “Essential Cinema.” The selection was made by five white men (and today the list of 330 films still does not include any films by Black filmmakers). After that, Clarke spent her time experimenting with a new, even more accessible medium, portable video, and in the streets, protesting the war.

Shirley Clarke’s Portrait of Jason and Ornette: Made in America are available from Criterion Collection.