In the first decades of the twentieth century, few Americans living in rural areas ventured very far from home. Many people never saw a big city or a landscape farther than fifty miles from the one in which they were born. Sons of privilege traveled, usually by train, to go to college. Wealthy families sailed to Europe for the Grand Tour. Ordinary people stayed home on the farm or minded the store. For hardscrabble families like Robert Rauschenberg’s, travel, when it happened, was often courtesy of the US military.

In this, the nineteen-year-old Bob (or Milton, as he was then still known) was very much part of his generation. The Navy gave Rauschenberg his initial taste of wanderlust, taking him in 1944 from his home in Texas first to Idaho and then to California. In 1948, Rauschenberg went to Paris to study art, where he met his future wife, Susan Weil, who introduced him to the world of museums and galleries. A few years later, the artist Cy Twombly, whose origins were of a more genteel version of Southern ramble, completed the job of opening Rauschenberg’s eyes to the wider world, especially to Southern Europe, with its monuments and antiquities, as well as to the life of cafés, rented rooms, tile roofs, and moonlit Mediterranean summers. Both men were attractive, photogenic even, the natural aristocracy of the poetic class, characteristically dressed in belted chinos and white shirts with the sleeves rolled up—this would become Bob’s lifelong uniform. And nearly always a tourist camera on a leather strap was slung around his neck.

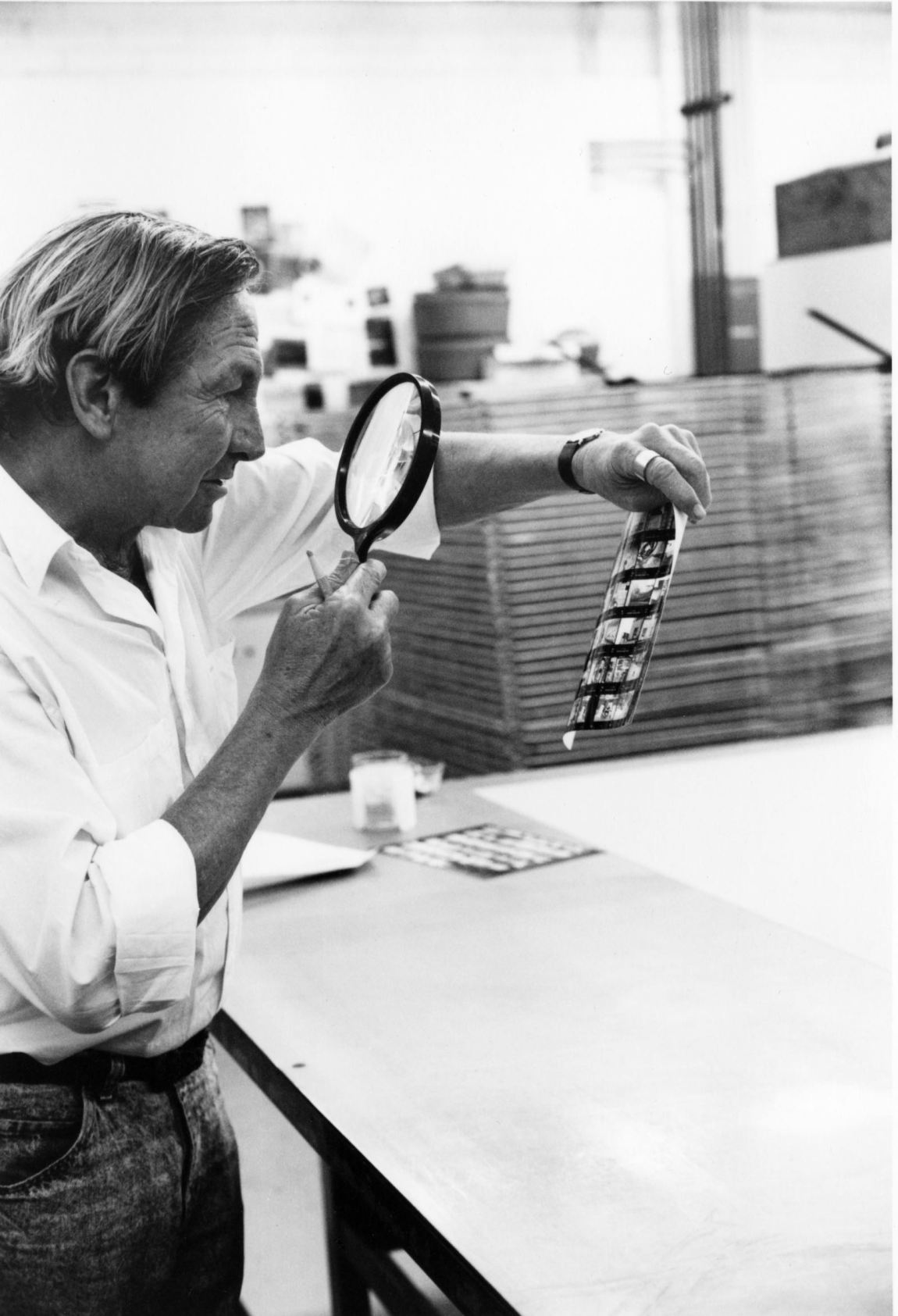

It was during these first travels in the early Fifties that Rauschenberg, equipped with a battered Rolleiflex, began to capture images on the move: signage, window displays, billboards, architectural details, friends, dogs and other animals, and the modes of his own transport, as well as the landscape seen through the window of a moving vehicle.

Whatever else he was or made or achieved, Rauschenberg, throughout his long life, was a kind of documentarian—a restless traveler, in circumstances comfortable and not, both observer and participant, for whom the camera was sketchpad, notebook, and diary: a record of his wide-ranging visual life. The photographs that Rauschenberg took in Rome in the early Fifties, and many of the images he continued to make throughout his life, are essentially in the Bauhaus tradition. These images have a strong graphic patterning, the main drama is one of light and shadow, and they are general in terms of subject—a detail of a stone figure, a doorway—their personification is at arm’s length, so to speak. But in 1969, possibly influenced by Andy Warhol’s use of the Polaroid camera, Rauschenberg made a series of photographs of striking—one wants to say heartbreaking—intimacy. The “here and nowness” of these images, their thick sensuousness and casual intensity, are unlike anything in his oeuvre.

Partly, it’s the film. The gray tones of a black-and-white Polaroid, along with its small scale, have an inexplicable power to draw in the viewer. It’s also the knowledge that the images developed “in hand,” as if by magic, in sixty seconds or less. And because there is no traditional negative, we know that each image is unrepeatable. A casual, throwaway shot of almost unbearable preciousness.

The twenty-two black-and-white Polaroids are mostly tightly cropped close-ups of bodies, both male and female. Attention has been paid to sexual parts and erogenous zones—pubic hair, nipples, buttocks, a penis, both in erect close-up and medium shot group portrait, a vagina held open by a woman’s fingers—as well as more oblique signifiers of tenderness and desire: a lock of hair curling behind an ear, the sparse hairs under an arm, someone’s bum half-submerged in bathwater. Other images are suggestive or weirdly fantastical and animated in proximity to their human costars. A stuffed buffalo head, some oranges under cellophane, water whooshing down a drain, a pot of water on the stove, a fireplug.

As a group, the Polaroids bear an uncanny resemblance to photographs made in the Thirties and Forties by another painter, the artist known as Wols. It’s unlikely that Rauschenberg knew Wols’s photographs—they had seldom been shown, and never in America—but the parallels, as well as the differences, are striking. Wols’s photographs represent the more garret-like version of bohemian existence: close-ups of raw meat about to be cooked, the pans used to cook the food, the aftermath of meals, a lit cigarette, a woman’s mouth, the lips thick with lipstick. In terms of the world they depict, Wols’s images of accidental beauty in the midst of resigned survival differ from Rauschenberg’s Polaroids; you can feel the lightening mood of the intervening decades. Rauschenberg’s subject is a freely expressed sensuousness and present-tense desire, not the forbearance in the face of adversity that we see in Wols.

Advertisement

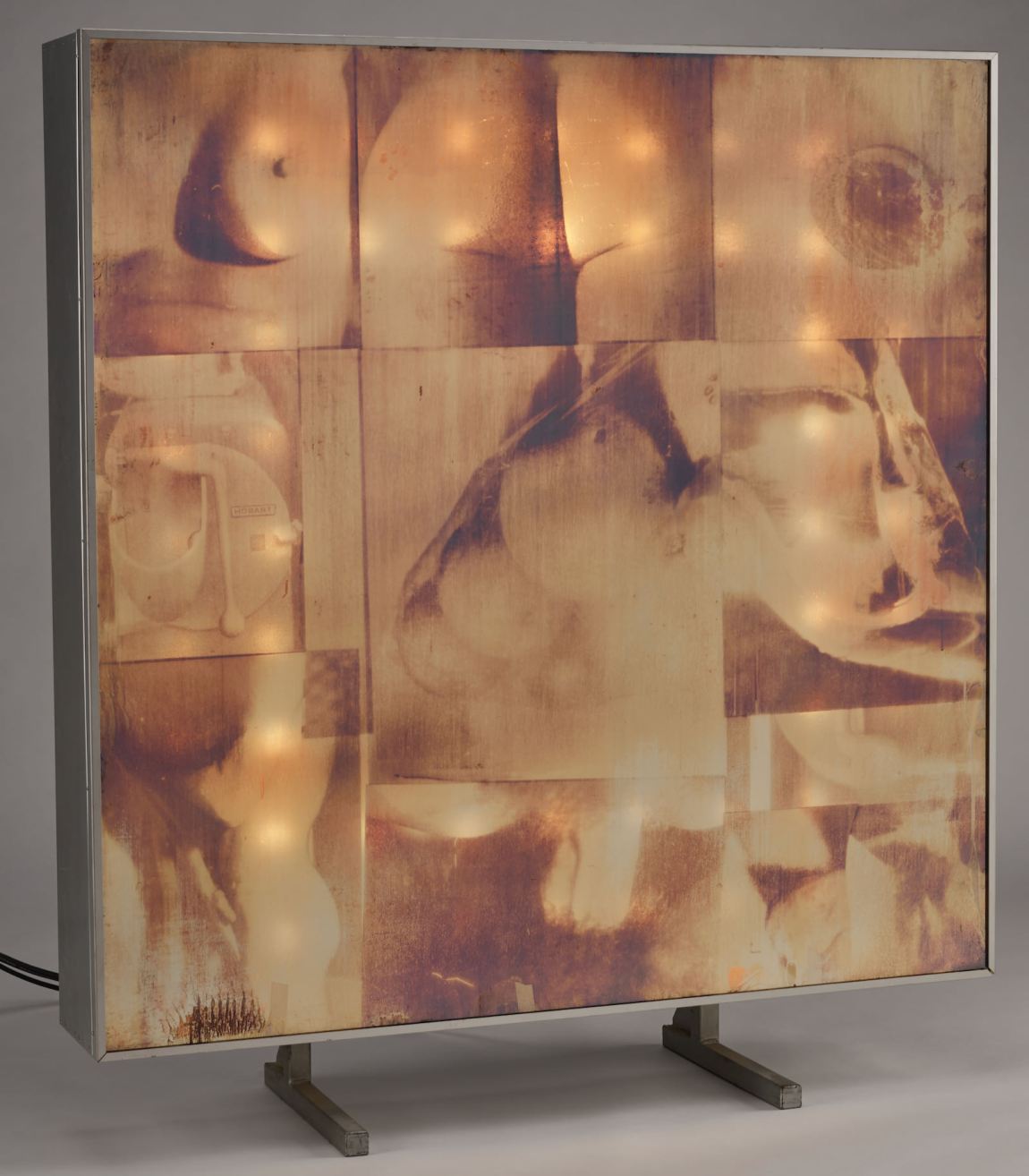

Rauschenberg’s Polaroids, which to this day have never been publicly shown, were used to make the image clusters for a series of complex constructed paintings called “Carnal Clocks.” These are large, freestanding Plexiglas light boxes that function as metaphoric timepieces; they tick with their own gently joking erotics. The Polaroid images were enlarged and silkscreened in loose overlapping grids onto Plexiglas panels that are held upright by thick metal frames resting directly on the floor. The images repeat from painting to painting in different positions and degrees of overlapped layering. Behind each Plexiglas panel are two square arrangements of lightbulbs: one nested within the other, which trace the perimeter of the face-frame and illuminate the silkscreened imagery from behind. The light bulbs are also the clockworks. The outer square of bulbs denotes minutes, while those of the inner square represent hours. The paintings are like large indoor sundials, with mysterious, erotic imagery that is semi-revealed as different lights are turned on throughout the day, mimicking the sun’s movements. The association of looking with the minutes and hours of the day is a brilliant, even profound conceit. Sometimes, the image scrum is so thick we don’t know what time it is.

As a group, the works are ravishing and thick with desire. According to Rauschenberg’s long-time curator David White, when the series was first shown at the Leo Castelli Gallery in 1969, not a single one was sold, even though Bob’s star was then near its zenith. Perhaps this says something about American prudishness in the visual arts, but we don’t need to go into that now. Suffice it to say that the “Carnal Clocks,” with their wonderful title, spill open, spread, and extend Rauschenberg’s generosity into the realm of the body. And it’s a “we” thing, too. Everyone has their own scale of desire. These clocks probe, they are permissive, inclusive, and touching. It is another kind of relational painting. Rauschenberg riddles on about desire and identity like your personal sphinx. And they are clock faces, silvering, smudging, and mirroring whatever questions or discomfort the viewer might have with paintings that were at the time liberating and prescient and remain fresh today.

*

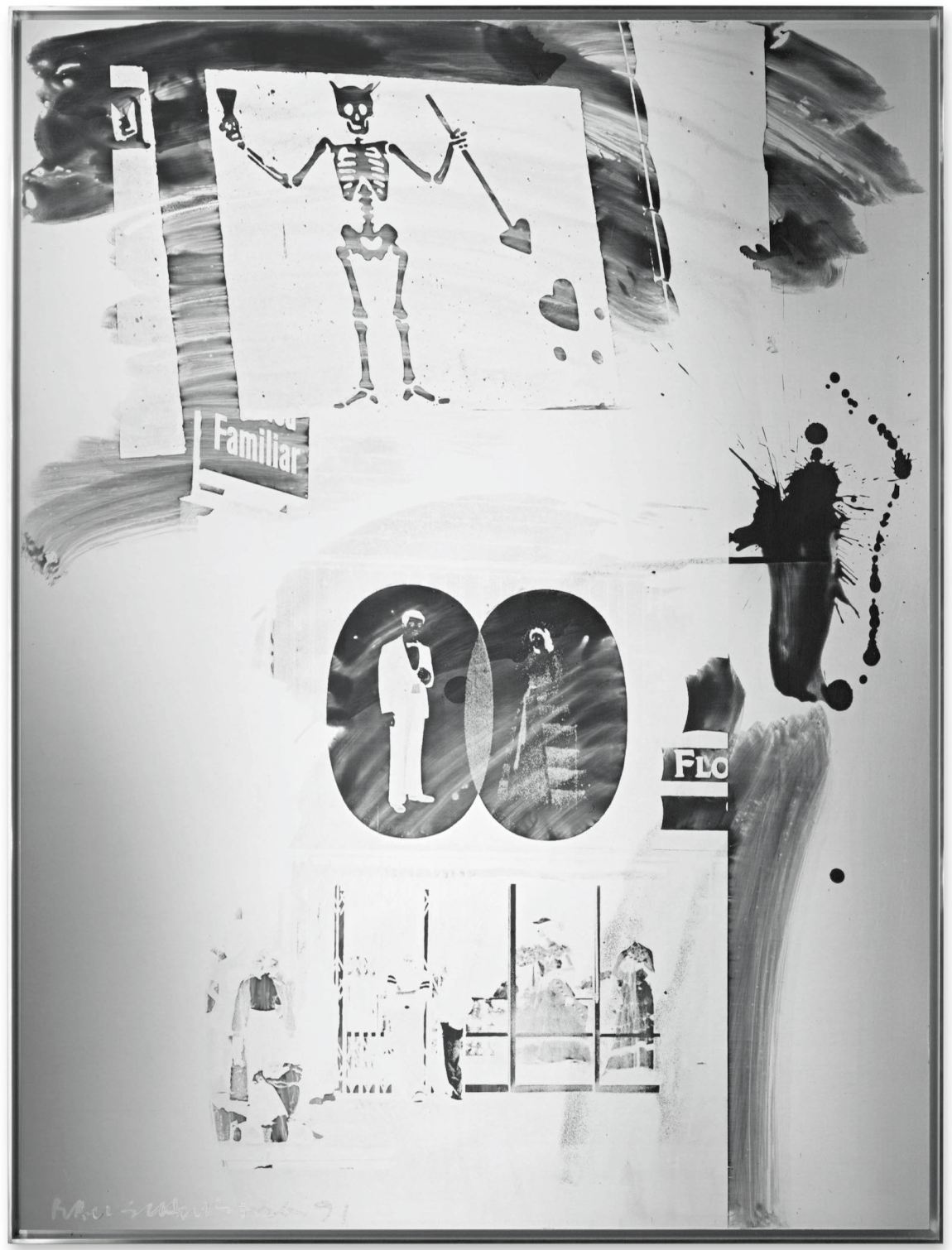

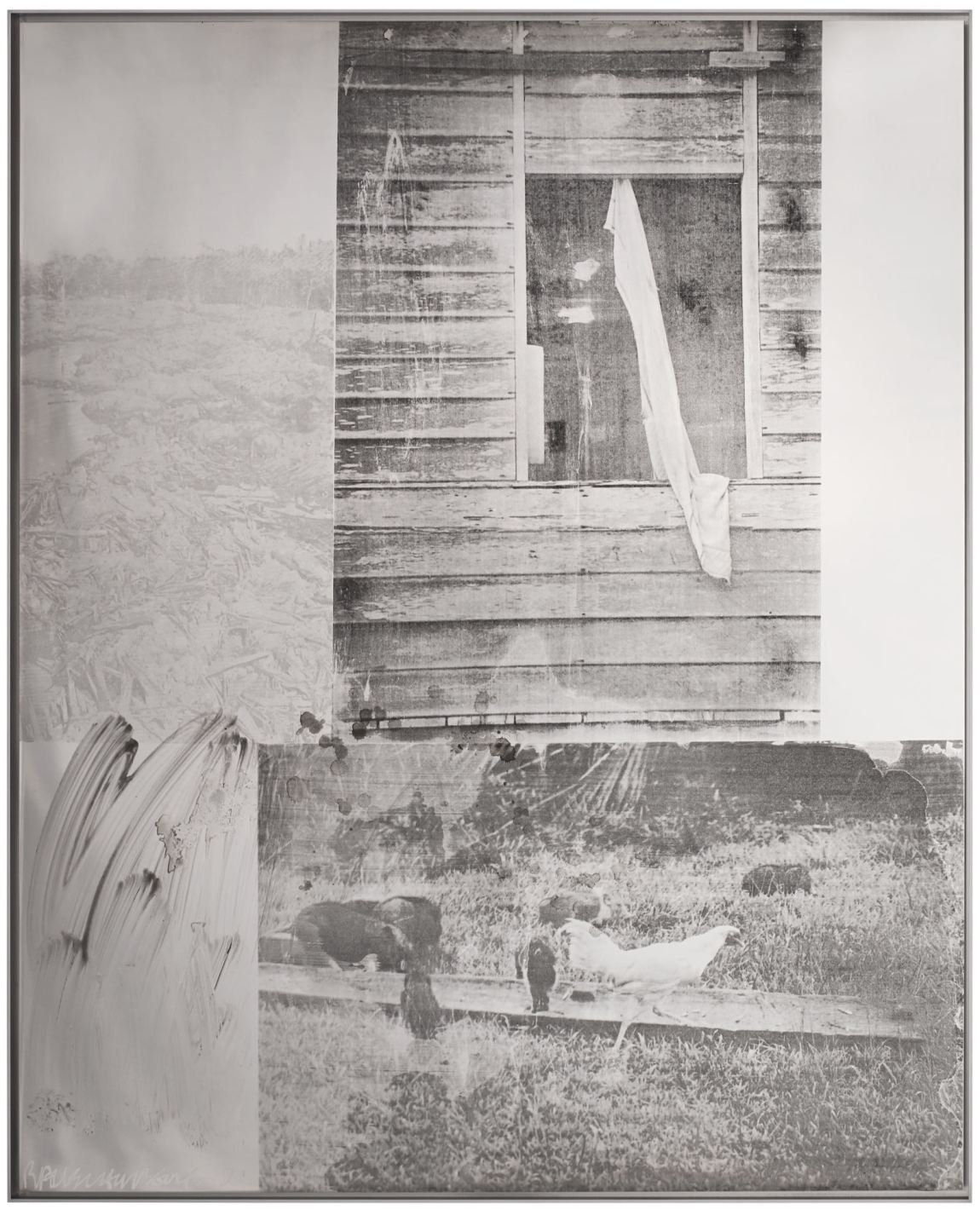

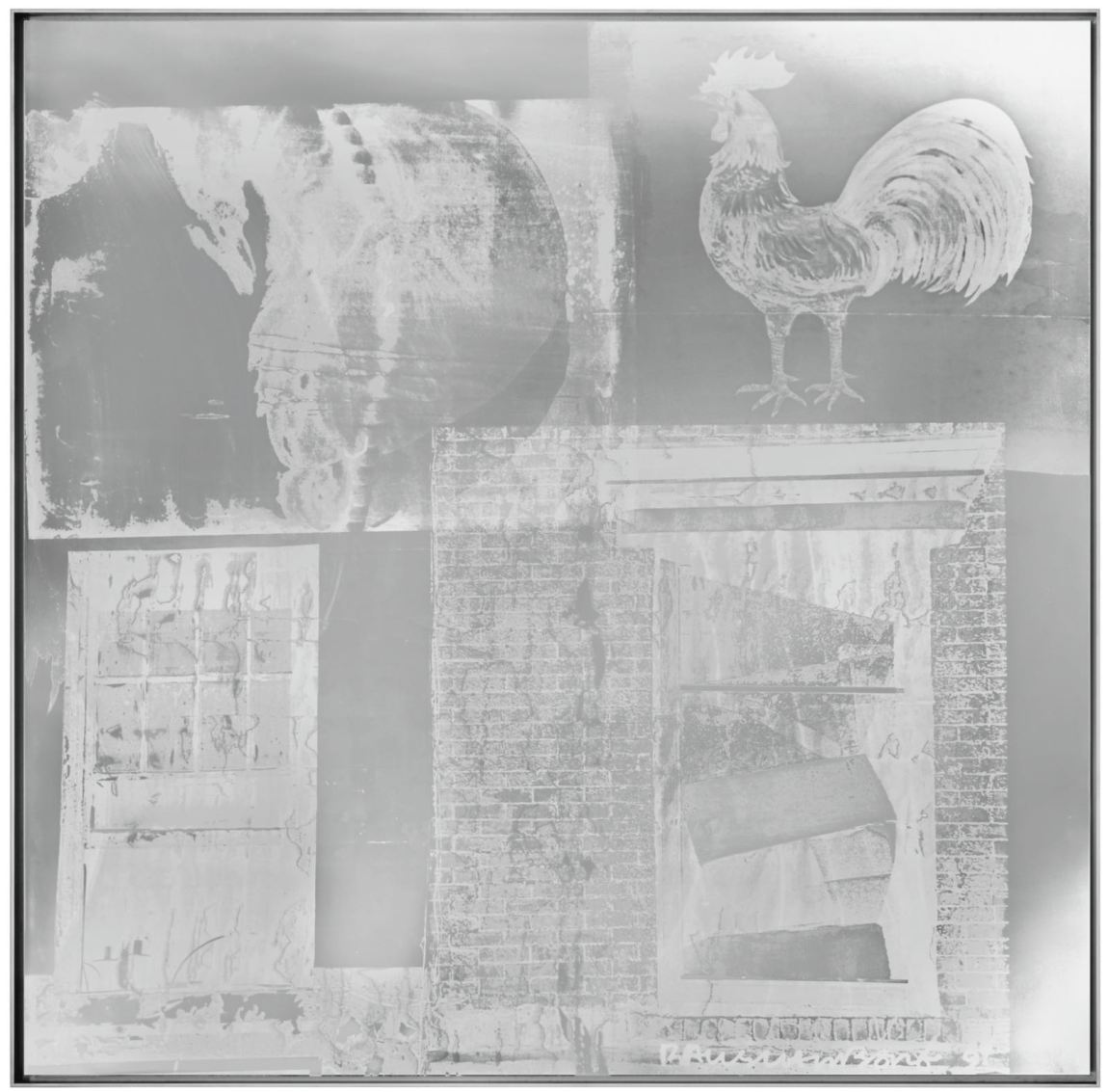

Rauschenberg’s many travels through large swathes of the globe—the southern United States, Central and South America, Europe, and Asia—resulted in images he then incorporated into his paintings, notably in two series, “Night Shade” and “Phantom,” both from 1991. Featuring scenes drawn from Berlin, New York City, Fort Myers, Santiago, and Charleston, among other places, the two series are related, their imagery shared or overlapping, though they differ greatly in appearance and affect. The “Night Shade” paintings are predominantly dark and bear the marks of vigorous brushwork, staining, splashing, and wiping away, as well as other removals. The overall effect is nocturnal and like stormy weather. The “Phantom” paintings are also monochromatic, but of a much paler shade of gray. Their metal surfaces are left mostly polished and highly reflective. The silkscreen ink seems to merge with the metal, making the value contrasts, the darks and lights, of the photographic image negligible. The “Phantoms” are therefore less “readable” than the “Night Shades,” which are absorbing, while the “Phantoms” hold the viewer back.

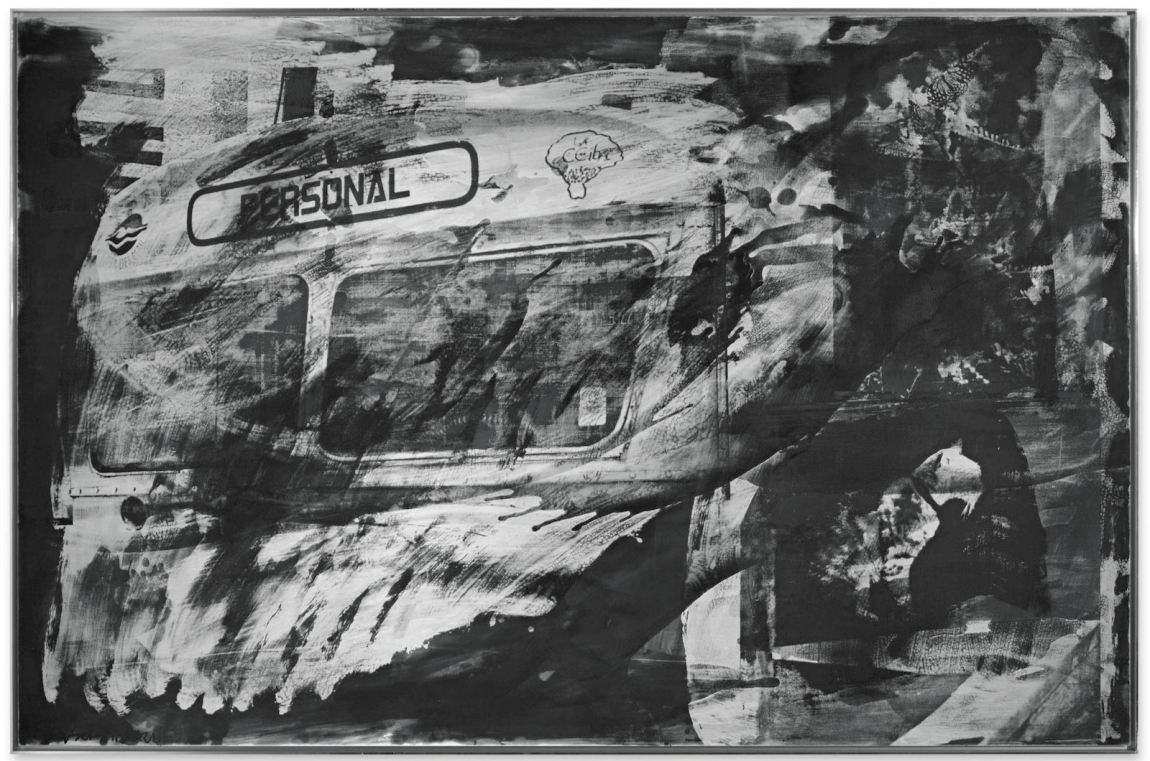

For the “Night Shade” paintings, Rauschenberg’s original photographs were resized and silkscreened onto aluminum panels using a transparent varnish that is resistant to the corrosive effects of the oxidizing agent the artist subsequently applied with a wide brush or paint rag. This alchemical fluid has the lovely name of Aluma Black. It produces a quality of black similar to that of tusche, a lithographic medium with which the artist was long familiar, and you can imagine Rauschenberg’s delight at its effects. Occasionally, images were screened a second time in black or white ink after the Aluma Black beauty treatment, which makes the painting look as though it spent the night outdoors, awash in its own raw experience. The surfaces swirl reflectively, their silvery, dreamy quality like so much brushy, subconscious spillage. This is painting weather, Rauschenberg weather—instinctive, open, and free.

With so much surface agitation, the images come into intermittent focus. They emerge out of the inky blackness, only to be overtaken by the enveloping murk. As a group, the paintings are sometimes witty, often mysterious, and ultimately stately, almost elegiac. One painting, Purr, shows an aging bus, its rounded front pushing into the scene as if it might crash through the picture plane, with a word visible in the rectangular slot over the high windshield—“PERSONAL”—either a designation that the bus has been used for private hire or a place name that begins to take on the quality of a fantastical, mythic destination. Rauschenberg loved signage and almost any form of visual shorthand and communication. Some of the images here are of billboards and road signs, the painted sides of buildings, and advertisements for tuxedos and medical equipment. And more images emerge from the darkness; one can make out a silkscreened cat gazing at the viewer and, even more faintly, a flutter of butterfly wings. These creatures carry on without us, seen or unseen, and they convey an ambiguous message: Don’t be fooled by the black-and-white world. Ride the bus to Personal or get off, if you need to.

Advertisement

The presence of the bus emerging from the pulled back curtain of the surrounding black ink is disturbing, an unsettling harbinger—a coup of opportunity and of staging. As it happens, the bus in Purr is an almost direct match, albeit from a tighter angle, for the opening and closing shots of Elia Kazan’s 1951 film version of Tennessee Williams’s A Streetcar Named Desire (1947), which is bookended by a wide shot of the streetcar itself, one in which the destination is visibly spelled out above the conductor’s window: Desire. It’s only a slight stretch to think that Rauschenberg, in his candid honesty and commitment to a refined poetical rhetoric of everyday life, could be our visual Tennessee Williams. We might even imagine Bob as a Williams character in a Williams play, just as Williams himself was a character in his own plays. The recurring Williams motif, and the dramatic arc of many of his plays, is the destruction of an innocent, a figure who embodies the realm of poetic sensitivity, by forces that are brute and unseeing, by the world in all its resistance to and hatred of difference.

At a slightly later time from Tennessee Williams, in the Sixties instead of the Forties and Fifties, Rauschenberg was forging a path from abstraction to an imagism that expressed a particular sensibility, one formed out of an innate innocence of character, a pantheistic identification with animals and all of God’s creatures, as well as inanimate objects. His work is fundamentally generous, with a natural-seeming gender fluidity a generation before that term existed in common usage.

Not all of the “Night Shade” paintings have the same sense of dark drama that we see in Purr. Pirate Love 2—Rauschenberg was always brilliant with titles—is a little slapstick. A skeleton with cat ears, a heart-shaped shovel. A shop sign for tuxedos. Or what looks like a cartoon sign—a pig wearing a dress and holding a pocketbook, counterbalanced with two hard-edged white arrows in Ms. P Goes To Town. One thinks of the tchotchkes of Mexican markets, colorfully painted dancing skeletons and characters of the afterlife, splashes of irreverence to enliven our encounters with death, loss, the passing of time.

The “Phantom” paintings keep the theater going. Their mirrored surfaces are left untreated, unblackened, and their image collages are often faint, ghostly, and in some places barely register except as visual white noise. Now you can step fully into a Rauschenberg house of mirrors; these paintings reflect us whole or in part, depending on where you stand. The photographic input is the banal or beautiful surface of city life: graffiti walls, a fire hydrant, fire escapes, and the kinds of things your eyes might come to rest on if you were smoking a cigarette on the threshold of Rauschenberg’s studio door. Or of life on the water: boats, a spit of land with a few palm trees on the horizon. In Litercy, a sign for “BOB’S Hand,” with a hand pointing off-screen, so to speak, continues the lighthearted mood. And you, yourself, as a reflection, are part of it. The painting/mirror invites you into the Rauschenbergian daily-ness and yearning, the casually relentless river of the ugly-beautiful flow of life.

*

Rauschenberg is often spoken of as a bridge to aesthetic movements that came after; that he led the way from Expressionism to Pop Art and its variants. Not so sure. Few artists, no matter their temperament, embody such a dramatic shift in the cultural zeitgeist. Consider the dominant art movements of the Sixties, from Pop Art to Minimalism. Taken together, they represent a wholesale rejection of relational painting, in which images and abstract forms were segregated, lest they contaminate one another. It’s no accident that Rauschenberg, arriving at the tail end of Abstract Expressionism, the most purely relational type of painting in the twentieth century, should have been a natural composer and arranger. And it should not be surprising that the artists who followed in his wake rejected relational art almost as pointedly as he had embraced it.

He was, in his own way, a narrative artist, too, or one who trafficked in narrative harmonies. Every image contains an element of narrative, even so-called abstract paintings, and one can discern in an image not only particularities of surface and style, but also degrees of personal information. Although Rauschenberg opened so many doors for artists who came after, few carried on his engagement with narrative, and, in fact, the dominant tendency in the Sixties and Seventies was to deny its existence. Rauschenberg’s narrative sense is a by-product of the elapsed time involved in making a work. That, plus the amount of time on the clock, a lifetime of experience.

It shows up differently in the work that followed his. If you were to place an early Sixties Warhol next to a late Fifties Rauschenberg, though separated by only a few years and obviously related in terms of sensibility and technique, it’s remarkable how clearly we can register a change in tone, a shift in the wind. One is relational, dispersed, anecdotal, and temporal, while the other is factual, immediate, non-hierarchical, and uninflected. One is handmade; the other is, by design, an industrial product.

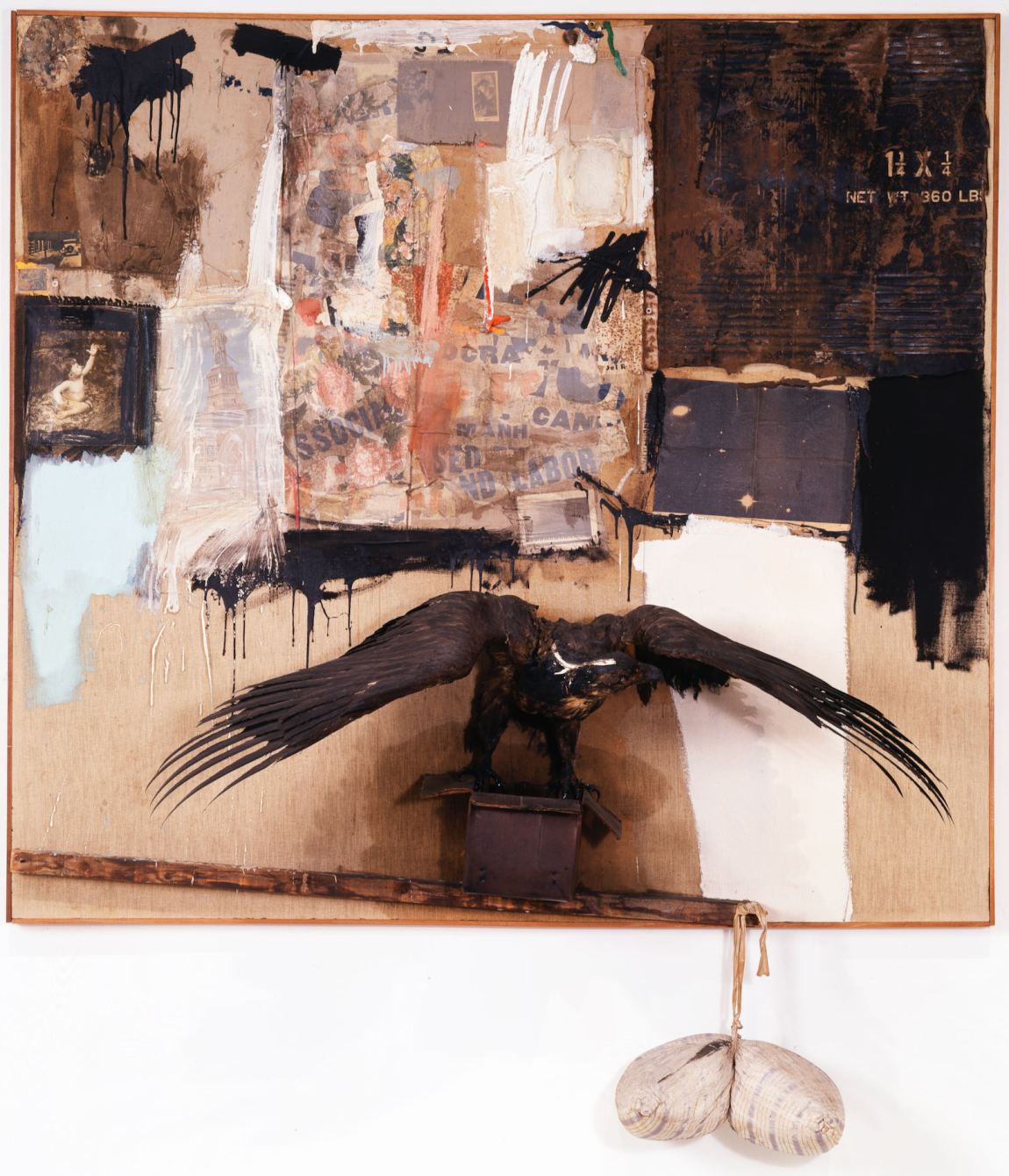

As a painter, Rauschenberg was always a compositional artist, an orchestrator. He would collect his materials walking down the street; something would attract his notice—a piece of bent metal signage, a cast-off chair—that most people would ignore. Often, it was an object that had been impacted by something else—something that had been run over, literally or figuratively. He would take these things back to the studio and use them in paintings in a way that felt necessitated. Rauschenberg had such a strong sense of pictorial architecture that whatever piece of detritus he threw at a painting, it pretty much landed in exactly the right place. That’s perfect pitch in painting. The thing is still the thing, but now it has other work to do. It was just waiting to be noticed, to be loved. It ceases to be a random piece of flotsam and becomes Bob’s piece of junk, a starring role in life’s moment-by-moment drama.

He was a fierce combiner, hence the name of his most famous series—“Combines” (1954–1965)—and the spine that runs through his multifaceted output. And if you know that Rauschenberg grew up in a fundamentalist Christian family in Texas before going to Paris to study art, and had love affairs with men as well as women, you begin to understand how he could mix paint on canvas with goats and chairs and birds. He believed in the naturalness of making the kinds of connections that both expressed and enlarged his own sense of freedom. These connections feel unforced but vivid, wild and also, somehow, right. What Rauschenberg was able to wrest from his juxtapositions is still surprising. To paraphrase Ezra Pound, it’s news that stays new.