A week before Thanksgiving, I had the special privilege of viewing “Working Together: The Photographers of the Kamoinge Workshop,” an exhibition at the Whitney about the African-American photography collective that formed in New York City in 1963 and continues today.

Inspired by Kamoinge’s spirit of community, I invited Maaza Mengiste and Rachel Eliza Griffiths, two artists whom I greatly admire, to join me. Mengiste is a photographer and the author of the novels Beneath the Lion’s Gaze and The Shadow King, the latter ofwhich was shortlisted for the 2020 Booker Prize. Griffiths is also photographer and the author of five books of poetry, including Mule and Pear, Lighting the Shadow, and most recently a hybrid of poems and pictures called Seeing the Body. I am a critic, photographer, and essayist. Together, we pored over the images arranged on the Whitney’s walls, considering the following: How have social concerns taken up by the workshop at its genesis developed over time? What do we stand to learn from Kamoinge’s original preoccupations and techniques for documenting the current moment, about Black visual representation, about pure aesthetics? Which of their themes anticipate our own?

The name Kamoinge means “a group of people acting and working together” in Gikuyu, the language of the Kikuyu people of Kenya. The members met weekly, exhibited and published together, and pushed one another to expand the boundaries of photography as an art form during a defining era of Black power in the 1960s and 1970s. Roy DeCarava, known for his portraits of Harlem and of jazz musicians, directed the workshop as an adviser and teacher from 1963 to 1965. The group organized several shows in its own gallery space, in a brownstone on West 137th Street, in addition to exhibitions at the Studio Museum in Harlem and the International Center of Photography. They were also the driving force behind The Black Photographers Annual, a publication founded by Kamoinge member Beuford Smith, which featured the work of a wide variety of Black photographers at a time when mainstream publications routinely dismissed them.

Each artist in the collective possessed a unique sensibility and developed an independent career, but the members of Kamoinge all shared a deep commitment to the power of photography as an art form and to one another as a support network. They also shared a dedication to community engagement—many of them taught their craft at art centers for urban youth, inspiring the next generation. Crucially, Kamoinge photographers depicted their Black communities as they saw and moved within them (as playful and stylish, and as the international drivers of cultural, political, religious, and musical movements), rather than as they were so often portrayed from without (as one-dimensional or fixed by poverty).

Though Kamoinge is still active today—contemporary members include the photojournalists Laylah Amatullah Barrayn and Ruddy Roye—the Whitney retrospective focuses on the collective’s first two decades. Included are approximately 140 photographs by fourteen of the early members: Anthony Barboza, Adger Cowans, Daniel Dawson, Louis Draper, Al Fennar, Ray Francis, Herman Howard, Jimmie Mannas, Herb Randall, Herb Robinson, Beuford Smith, Ming Smith, Shawn Walker, and Calvin Wilson. Nine of these artists still live in or near New York City. Their photographs provide a powerful and poetic perspective during a time of dramatic social upheaval. Organized by theme rather than photographer, in line with the group’s founding ethos, the show eschews individual artistic accomplishment in favor of collective vision and communal production.

What follows is an edited conversation I had with Mengiste and Griffiths about “Working Together,” on view at the Whitney through March 28, 2021.

—Emily Raboteau

Emily Raboteau: Isn’t it a visual feast for sore eyes to gaze at black-and-white gelatin silver prints arrayed on a gallery wall after spending so many months staring at screens during pandemic lockdown? So many of these gorgeous Kamoinge pictures were taken here in New York City, but I’m struck by how many were taken elsewhere—the deep South, overseas on military service, or exploring cultural and political interests in Africa and the Caribbean. I recognize so many locales that those of us in the Black diaspora with the privilege to travel seem drawn to as sites of healing, home, kinship, identification, liberation, and fascination. Maaza, I was reminded of the internationalism reflected in your own work, and Rachel Eliza, of your Southern roots and pictures. Which images from sites outside of New York City resonated with you?

Maaza Mengiste: When I saw Shawn Walker’s Women in the Field, the first thing that came to mind was the Three Graces, those daughters of Zeus who gave beauty to the world in all its forms: physical, artistic, intellectual, moral. These women, especially those two leaning on that wooden tool with their arms draped so elegantly over it, seemed to me to be a sign of both natural elegance and physical strength. But it’s difficult for me to look at this image without putting it in some context: this is Cuba 1968, nine years after the revolution. It’s after the euphoria of overturning imperialism. Those women aren’t looking into the distance (one, in fact, might have been looking into the camera if she hadn’t blinked) with expressions of resolution or fervor.

Advertisement

There’s something else there, a knowledge that’s hard earned and not so easily given up: the work that must take place after revolution, after the struggle ends and quiet settles in again. What does it mean to mold everyday life into the shape of a dream? We have to look at this image from several perspectives: Cuban, American, male, female, urban, agrarian, capitalist, imperialist, photographer, subject, etc. This photograph is one way that an American might look at a Cuban. It’s a way of seeing women in a revolutionary country. It is an image of strength that is without the frayed edges, the intimate betrayals, [and it shows how] stories of fortitude often reveal something else just beneath the surface. The subjects are clearly posing. Did they choose to stand this way? Did they come together of their own accord? When they walked away, what did they take with them of this moment?

I see a definition of womanhood that pushes back against the notion that beauty sits close to fragility. Yet I wonder what else is here that we cannot know, of what it means to be a woman in a liberation movement. What does freedom mean for each of these three? I don’t think some of these questions can be answered so easily, each response leads to another complication, but this tension is why this photograph kept creeping into my mind, weeks after we had our visit. It still holds me at attention, even now.

ER: Rachel Eliza, which images taken in New York City most delighted you? What innovations, experiences, and emotions do you observe being communicated here? I’m also interested to know if you recognize any of your own subjects or techniques represented.

Rachel Eliza Griffiths:What feels so powerful to me is the grasp of a diaspora that is visible in so many of the Kamoinge images. Within the vision of the community, each photographer has a voice that is fully realized. Ming Smith’s image of these two Black women in Harlem who are clearly amused, unbossed, and unbothered is personal. Smith’s recognition of the women speaks personally to my own needs and impulse, as a photographer and as a Black woman, to let Black women shine without any filter, any explanation, because I know how it feels to try to explain or persuade others that Black women have sacred weapons like laughter and joy.

The women in Ming Smith’s image have earned their ecstasy on earth and beyond. These are Fannie Lou [Hamer]’s generous, determined sistren. Also, their implicit refusal to suffer fools! The grace of these elegant ladies who have likely seen and endured so much made me think of them as young girls together growing up in the church and in the living, expansive gospel that is Harlem, and that is, too, part of how I visualize Black womanhood––we are holy in our own visions, politics, and languages across our diaspora.

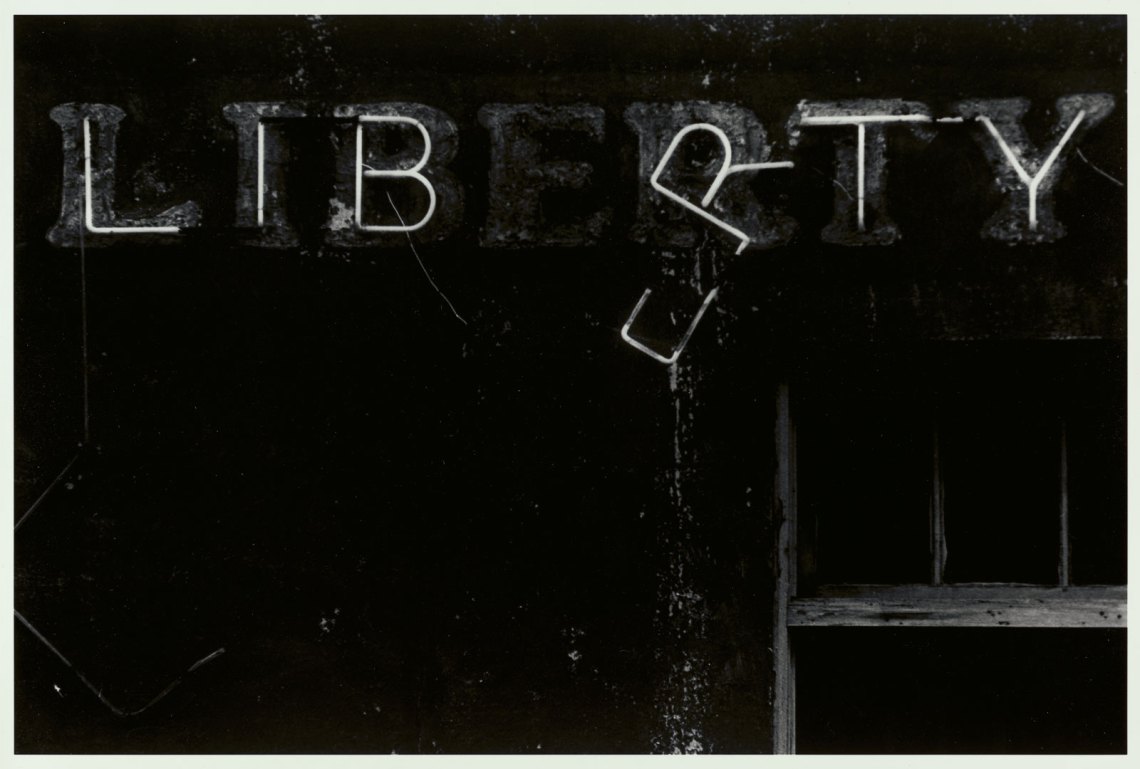

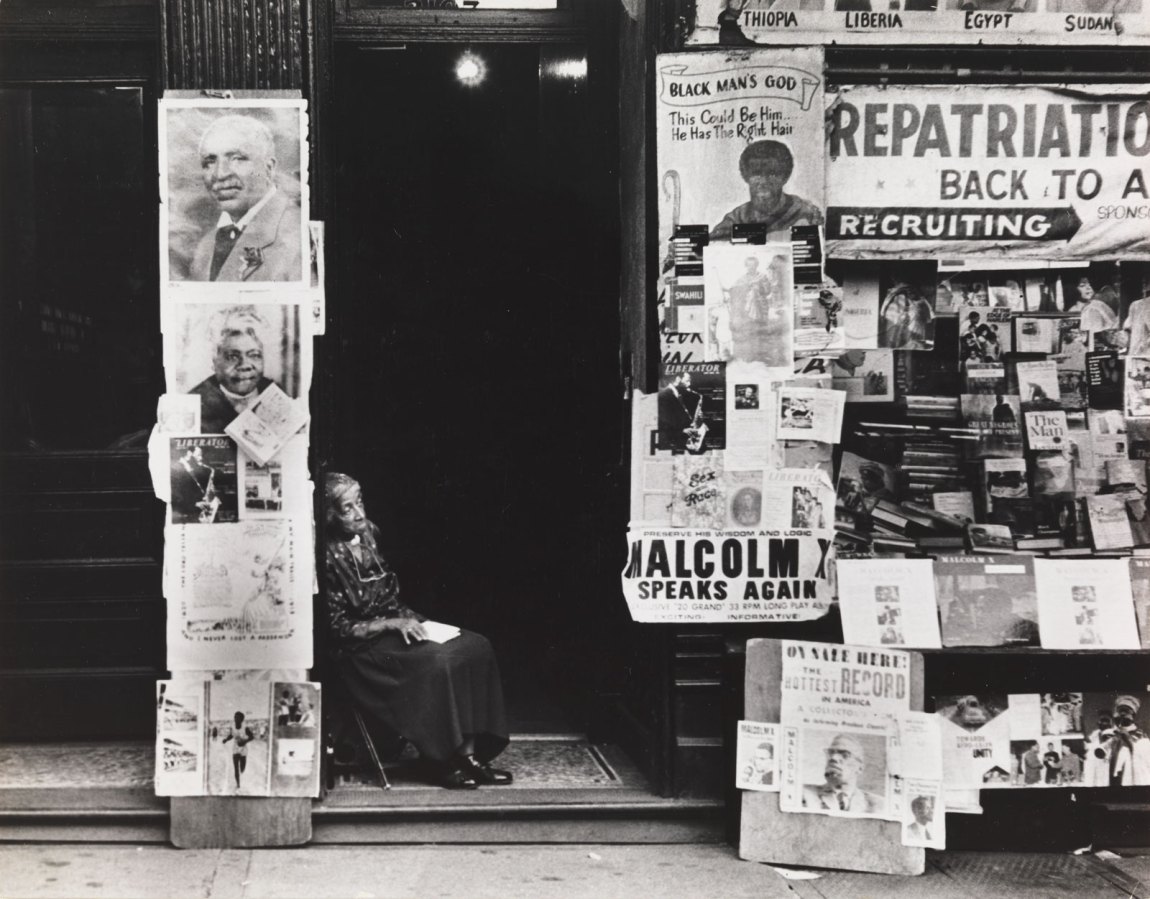

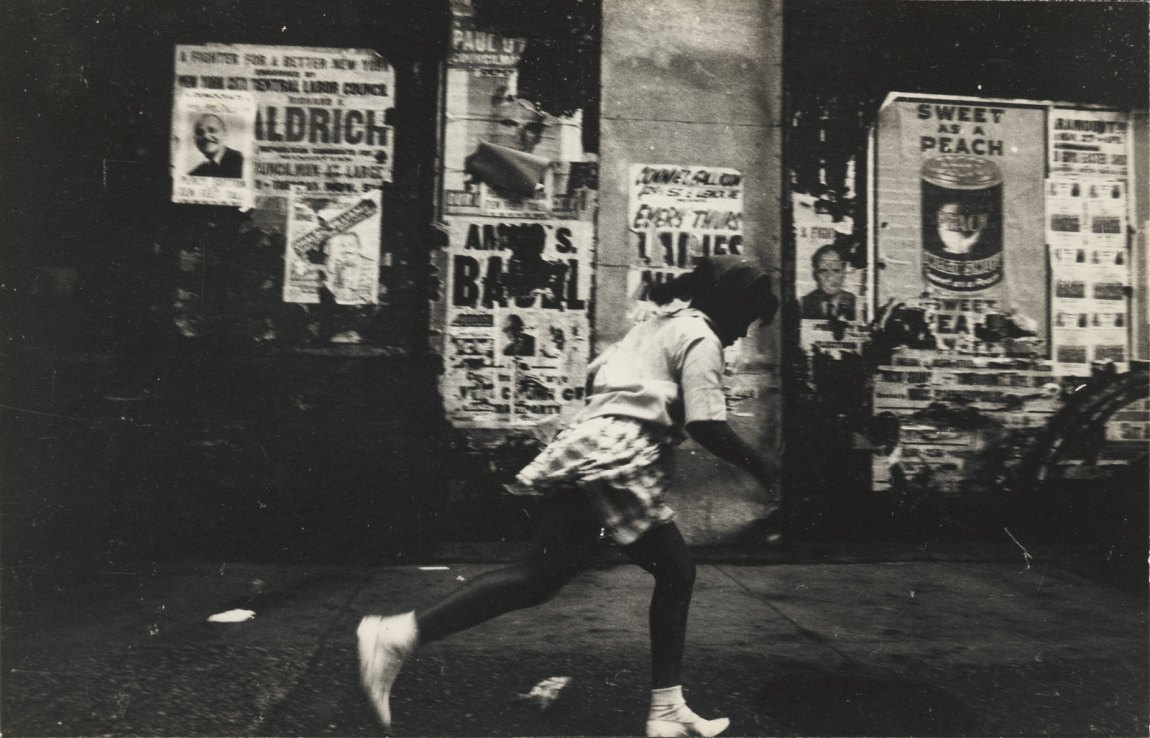

ER: Amen. I’m especially glad you highlighted a photo of Ming Smith’s since she was the only woman among Kamoinge’s founding crew. A recurring theme I noticed in “Working Together”was wall art and the influence of Walker Evans in his obsession with American signage, like billboards and graffitti. That broken LIBERTY sign—it’s almost too on the nose, but how could one not take a picture of it, coming, as we do, from a tradition of liberation struggle? I have this documentary impulse myself when I wander the city—to pay attention to the commentary or abstraction of the walls as a living backdrop. How, for example, signage fails or succeeds at defining us; decays around us; frames our posture; intrudes upon or expresses our condition; makes fluid the line between conceptual and real, photojournalism and fine art. I saw this and so many other recurring themes and impulses among Kamoinge’s photographers that parallel and predate work the three of us are making.

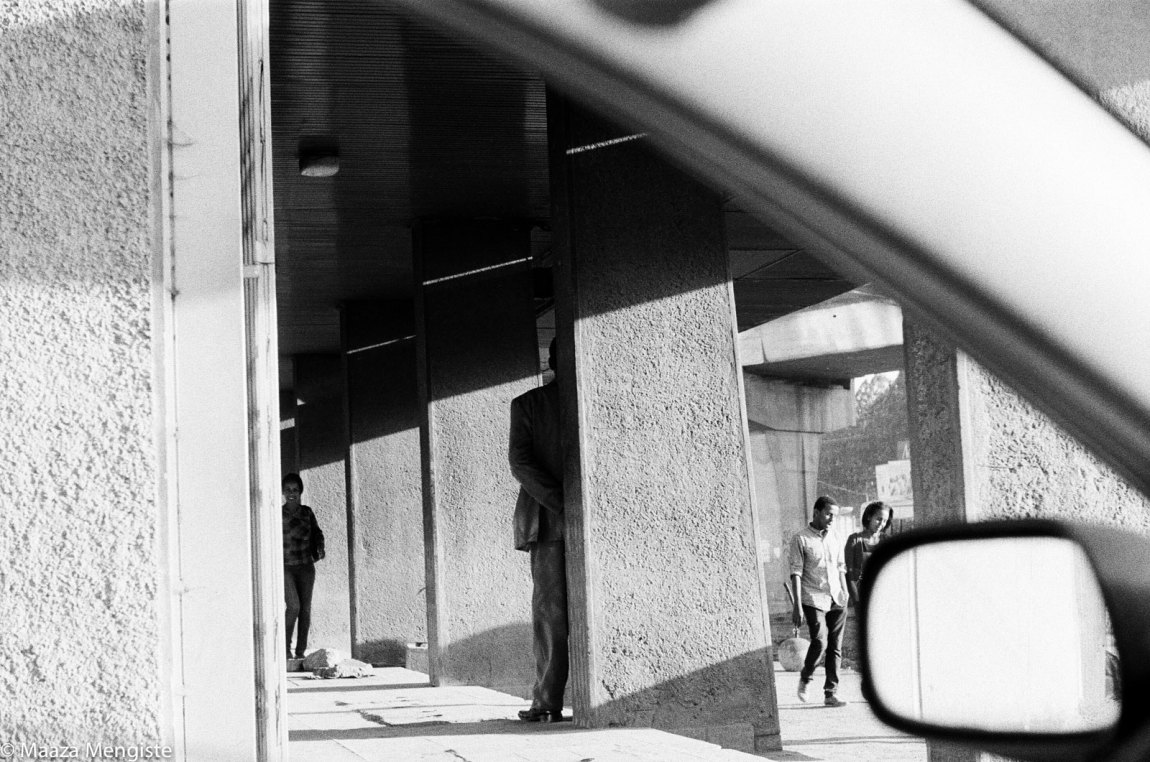

Here are a few of shots of my own in this vein.

ER: What I love most about Kamoinge is that it’s not static—it’s a dynamic workshop, meant to advance and promote the artistry of those involved. As a Black art collective, it was a precursor to the Dark Room Collective, a writing workshop and reading series founded in 1988 which in turn inspired the formation of the Cave Canem Foundation in 1996, organized to remedy the underrepresentation of Black poets in MFA programs by providing mentorship and a publishing network. In that sense, Kamoinge is a model of self-determination.

Care to elaborate on anything you learned as a photographer from specific photographs in this show? In other words, what images most inspire you, with respect to craft?

REG: I appreciate the particularity and fluidity that you feel each photographer is offering to the workshop.

That notion of offering, breathing, and improvising makes me think of jazz and Roy DeCarava’s images that dance and blur, which, despite picturing motion and mood, remain mindful. Like DeCarava’s images, the photographs of the Kamoinge Workshop also seem to value intuition as much as craft.

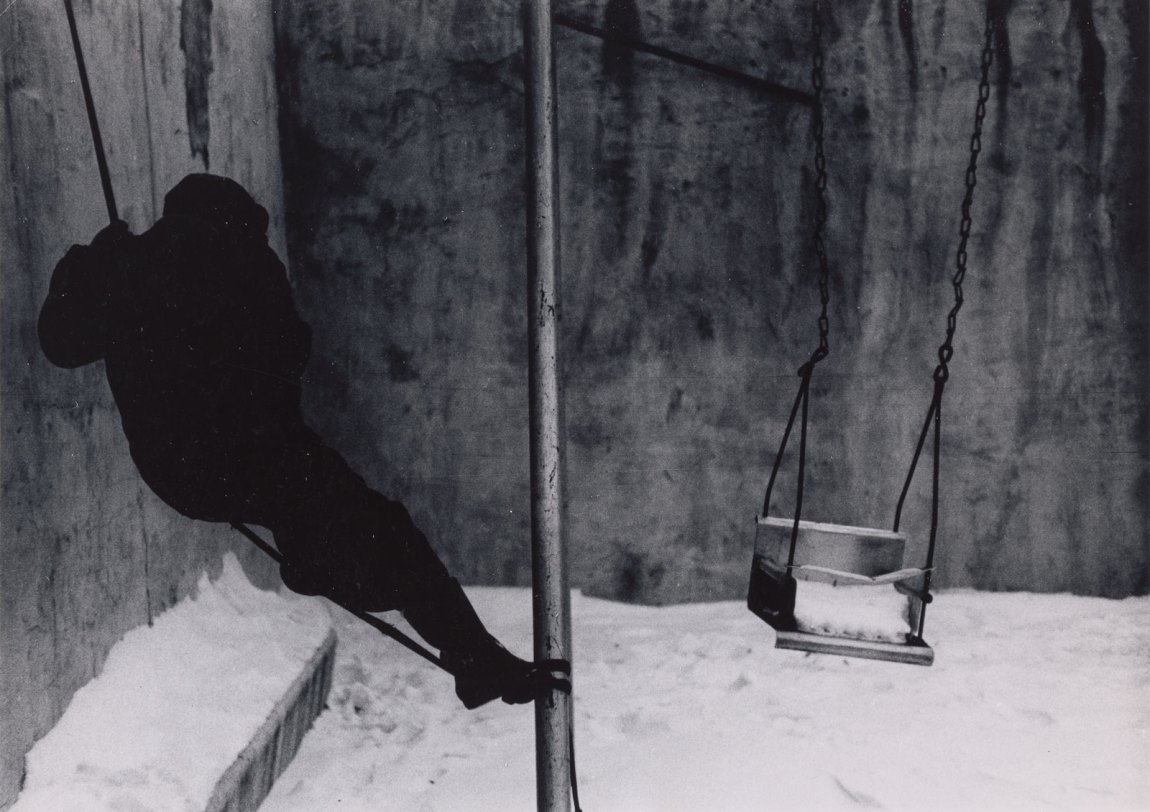

Beuford Smith’s Boy on Swing, Lower East Side deeply moved me. I see the energy of Jacob Lawrence, Romare Bearden, and the late painter Noah Davis in this image. It is literal and abstract, yet specific. I hear the voices of characters from August Wilson plays and I think of Toni Morrison’s Milkman Dead from Song of Solomon—what kind of boy Richard Wright’s Bigger Thomas had been and how in some of the ways James Baldwin speaks of his own boyhood there is an echo of dreams being ripped away, promises broken.

I think of twelve-year-old Tamir Rice and how he was murdered by police while playing in a snowy playground. I also hear Robert Hayden’s final question in his poem “Those Winter Sundays”: “What did I know, what did I know/of love’s austere and lonely offices?”

Smith’s composition and use of contrast is breathtaking. The photograph hangs on the tension of what is suggested. There is a melancholy, a provocative meditation on the relationship between the figure aiming itself towards a pole and the empty, snow-covered swing that is moving to meet him. The whole thing feels like the blues to me.

MM:There’s a momentum in each of these photographs. You can feel it the minute you walk into the exhibit and gaze at that large portrait of the founding Kamoinge members, those beautiful, radical artists who made it a mission to reshape how Blackness was imagined. You see the energy in their gazes and the charge they put into their work. It binds their varied approaches together. It reminds me of what has fascinated me about photography since I was a child in Ethiopia, playing on the floor of our sitting room, staring up at a wall crowded with black-and-white studio portraits of myself as a baby and other family members. I imagined those photographs as real human beings frozen and flattened onto paper while another version, more limber and free, kept moving forward.

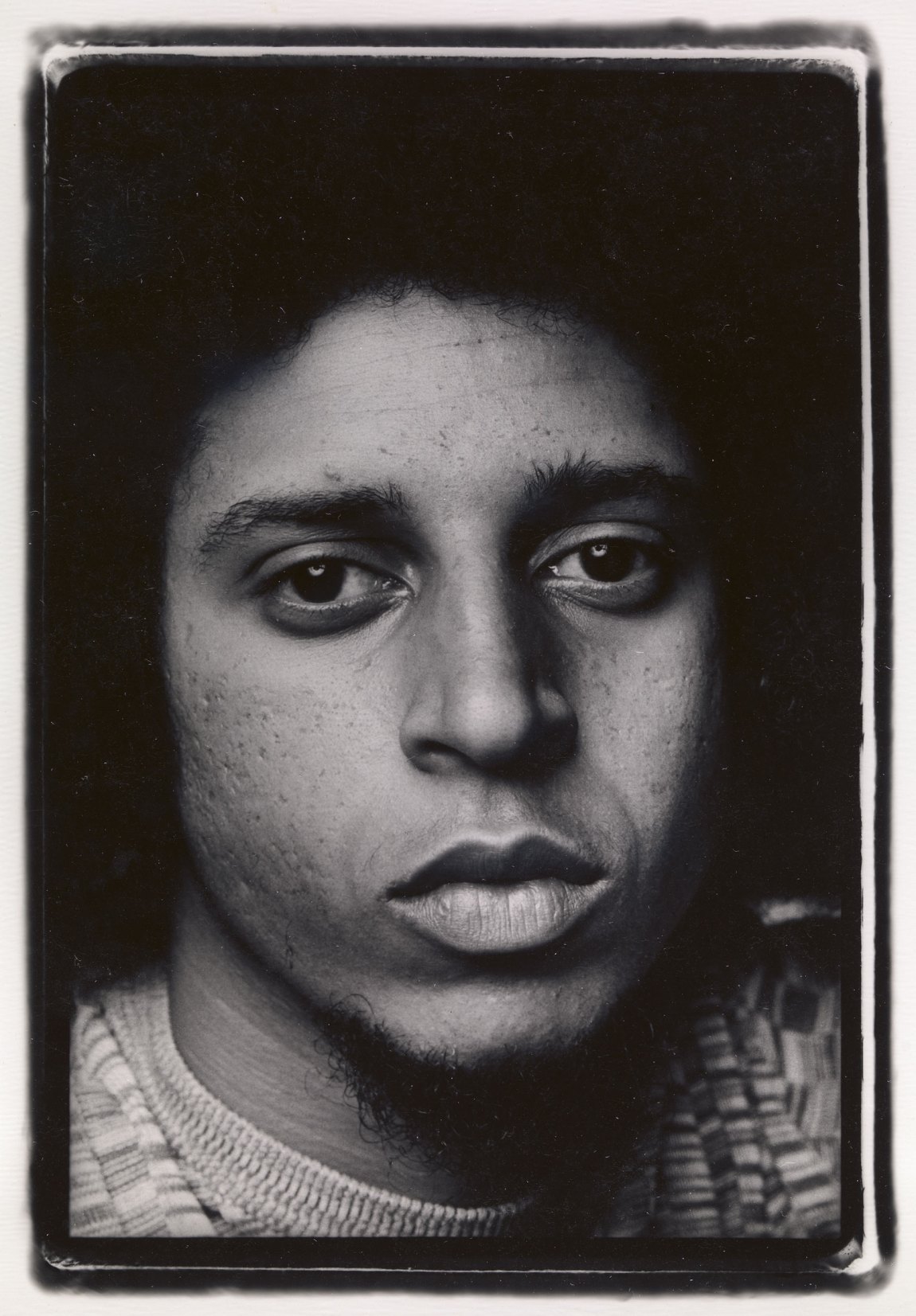

The early Kamoinge members wanted to unfreeze their subjects. This is why, I think, so many of these photographs feature people in motion, running, jumping, laughing, walking tall, bent over a burden, or paused only briefly in the middle of a daily task. Black people around the world have been the subjects of a documented, visual framing intent on freezing us into an inaccurate and antiquated narrative. According to those kinds of images, the world kept moving forward while we stood still: anachronisms, stunted and incomplete. Not so, the photographers of Kamoinge say. And they show it.

I’m also intrigued by the lyricism and, as Rachel Eliza says so beautifully, the musicality of these photographs. Anthony Barboza’s photograph carries the essence of jazz improv: sharp lines and surprising cutaways, that unwavering attention to an idea—like a melody that reaches out while you watch and hold your breath, uncertain how you came to feel what it is you’re feeling. And just when you think you know what’s going on, you notice the finer details of that young man’s hand, the fine creases in his fingers. And then, over there, watching you: a child’s face rises to the surface of the photograph like a mirage. Who, exactly, is doing the looking and who is being observed?

I noticed again and again the way that objects were shown in these images. Windows, walls, doorways. Barboza and others were working with what is already in the world, moving into it, and learning to bring a part of it under their control: objects, yes, but also light and shadow. For a brief moment, in the making of their photographs, they held dominion.

ER: What parallels do you both see between that moment of social upheaval and surge of Black arts seen in some of their work, like the crowd at a speech by Malcolm X and a loving portrait of Amiri Baraka, and this of our own era, colored by Black Lives Matter protests and what might be described as a recent renaissance of Black cultural production?

REG: The need to document and to tell Black narratives was as necessary and organic for them as it is for us right now in these charged times where our lives, as theirs were, remain endangered. There is too much at stake for us to risk ever allowing anyone but ourselves to tell and to show us who they think we are. We know what we know. We see and we remember, through their work and those before them, the history that is threaded through our eyes.

We are saving our bodies, our joys, and our rights for ourselves and for those who will come next. There is certainly a wellspring of Black photographers who have helped me give myself permission to reject oppressive imagery of Black life.

Ming Smith

Ming Smith: Sun Ra Space II, New York City, 1978; for more on Smith’s photographs of Sun Ra, see Namwali Serpell’s essay here.

MM:Early Kamoinge photographers wanted to preserve and reclaim notions of Blackness that connected Cuba to New York to Florida to Senegal and other places around the world. That diasporic connection came back to me when, this summer, while stuck in Zurich due to the pandemic, I went to a Black Lives Matter march. I wasn’t sure what to expect. I found myself surrounded by every race, nationalities from nearly everywhere, all [out in the streets] in honor of George Floyd’s life and in protest of police brutality.

It hit home again how powerfully the African-American experience resonates across borders. The world is not white. It has never been white. We have been here, in Europe, in Asia, in every part of the world, because we have always moved: between homes, between countries, but also between intellectual and artistic spaces.

ER: Right. You’re reminding me of Kehinde Wiley’s ambitious “World Stage” project to represent Black people all over the world, including in Israel and China, in poses styled after eighteenth- and nineteenth-century European figurative paintings.

MM: I see those close-up portraits of the Kamoinge members as another assertion of this. What is contained in the planes of a face, behind those eyes? How much history is held in those features and how can we learn to see that? I think Velázquez was asking the same question in his 1650 portrait of Juan de Pareja, recognizing the migrations of body and intellect that this singular man contained. The artists working today continue to reclaim these notions of multiplicity and internationalism. I have hope that with each passing generation, it will get more difficult for the rest of the world to forget this.

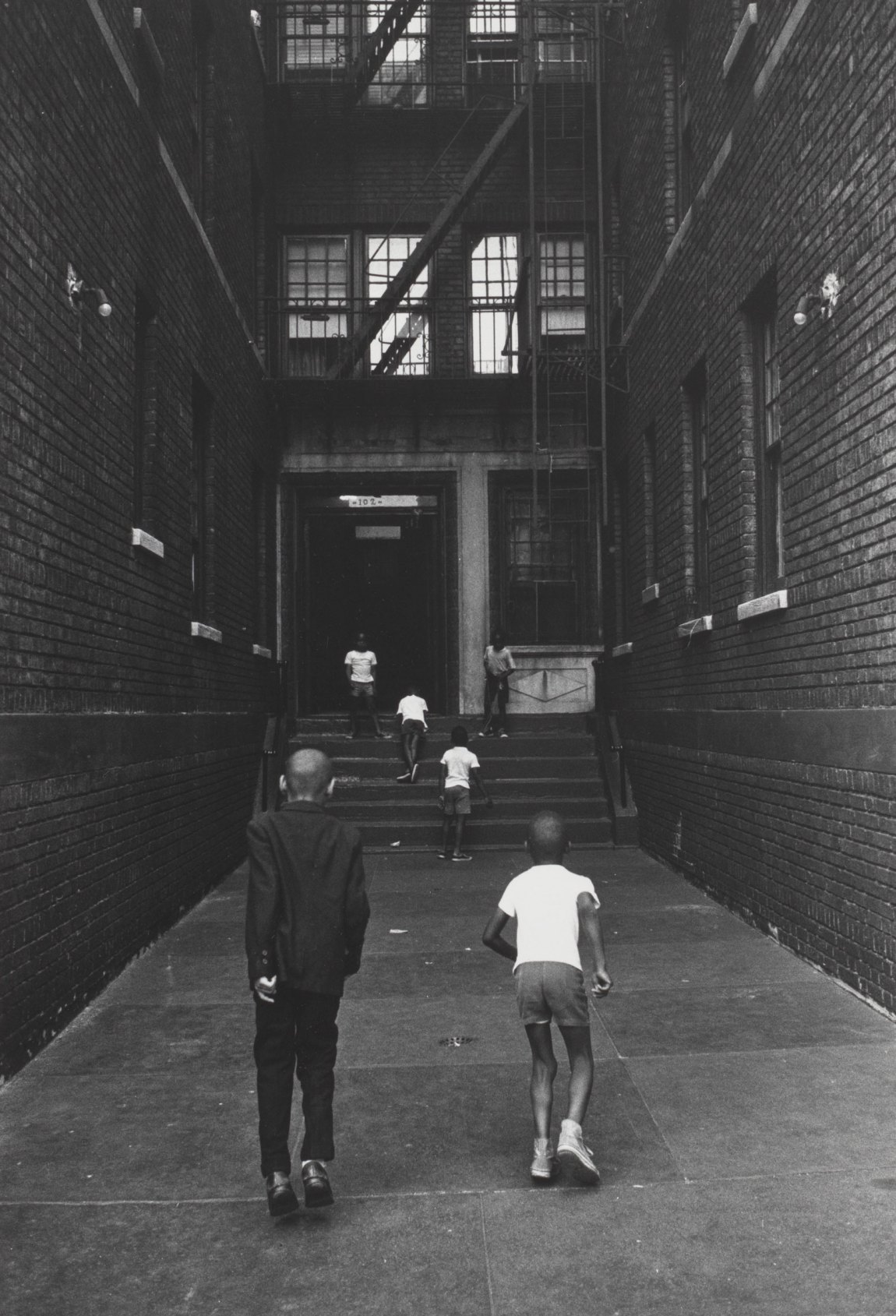

ER: Maaza, one of the images that you and I stood in front of for a long time at the exhibition was by Calvin Wilson, of a group of boys playing in a building courtyard. Is this a “decisive moment”? Is it staged? How many shots of the scene did the photographer take to capture this one perfect picture? I have no idea. What impressed me, beyond the marvelous symmetry, was seeing the joy and surrender of Black children at play in a confined urban space. It’s something I see my own children doing, probably reciting the same rhymes to figure out who’s going to be “it”: “Bubblegum, bubblegum in a dish/how many pieces do you wish…”

MM:We were both completely captivated by that photograph. What comes to mind here for me is time, the progression and cyclical nature of it. If I squinted, it could be a photograph of the same boy in motion, a trick of the camera that sneaks its way into time and offers us this young boy in movement, without ever fully letting him go. He keeps racing forward, dragging time with him, standing at the top of the stairs waiting for himself to catch up even as he is at the other end of the courtyard, gorgeous in his suit and shiny shoes, caught mid-leap, ready to soar.