I

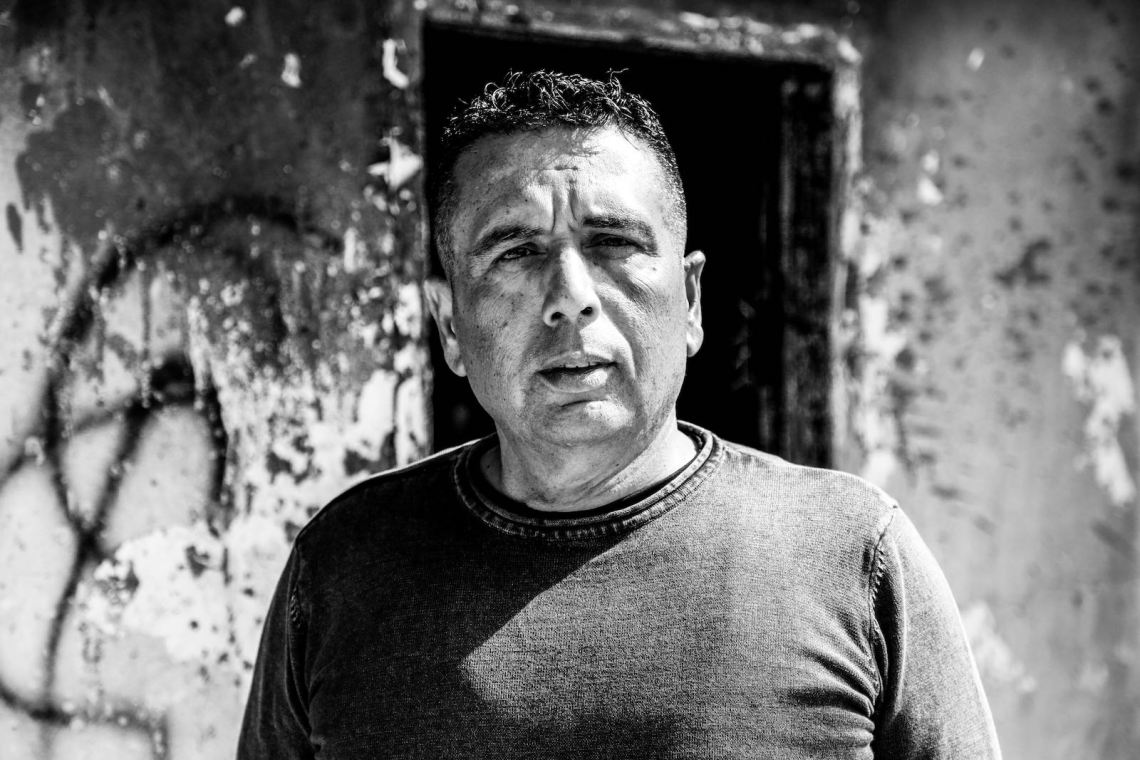

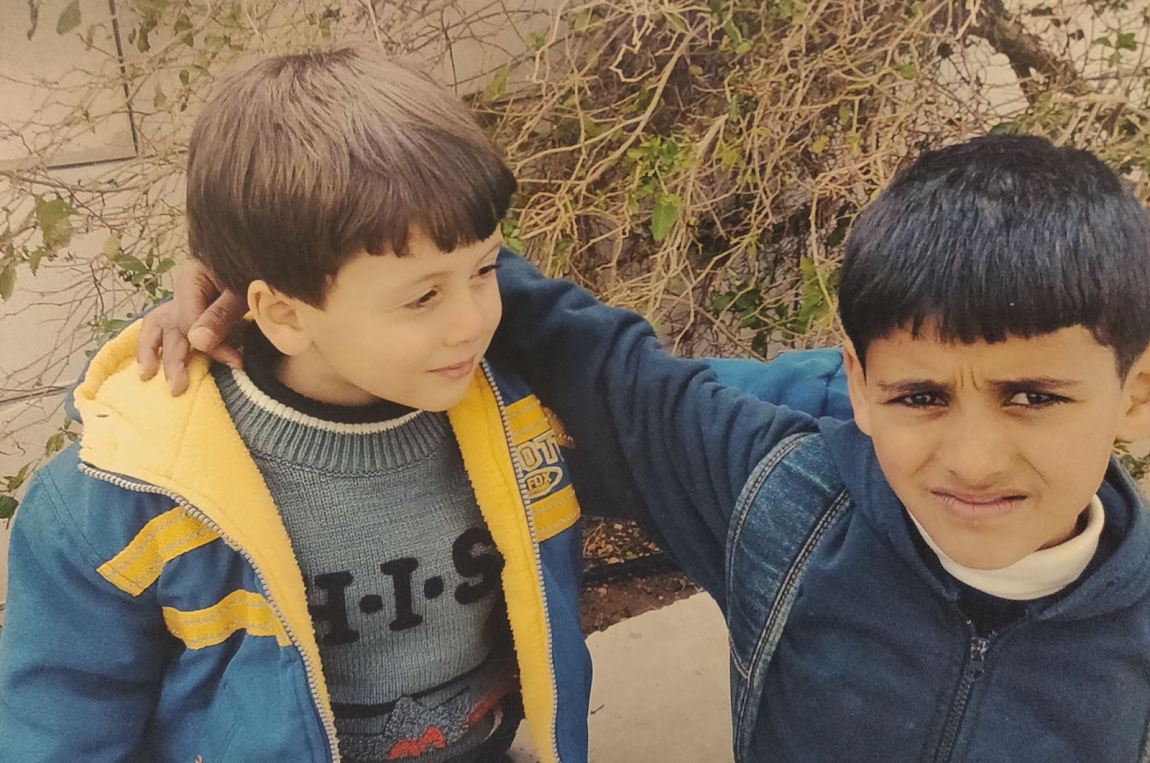

On the day before the accident, Milad Salama could hardly contain his excitement for the kindergarten class trip. “Baba,” he said, addressing his father, Abed, “I want to buy food for the picnic tomorrow.” Abed took his five-and-a-half-year-old son to a nearby convenience store, buying him a bottle of the Israeli orange drink Tapuzina, a tube of Pringles, and a chocolate Kinder Egg, his favorite dessert.

Early the next morning, Milad’s mother, Haifa, helped her fair-skinned, sandy-haired boy into his school uniform: gray pants, a white-collared shirt, and a gray sweater bearing the emblem of his private elementary school, Nour al-Houda, or “light of guidance.” Milad’s nine-year-old brother, Adam, old enough to walk to school on his own, had already left. Milad hurried to finish his breakfast, gathered his lunch and picnic treats, and rushed out to board the school bus. Abed was still in bed.

On most days, Abed worked for the Israeli phone and Internet service provider Bezeq. But that morning, he and his cousin had plans to go to Jericho. They stopped at the nearby butcher’s, in Dahiyat al-Salaam, “neighborhood of peace,” beneath the Mount Scopus campus of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. The owner, Atef, was a friend of Abed’s, and it was unusual for him not to be at the shop. Abed asked an employee to check where Atef was. Atef lived in a different part of municipal Jerusalem, Kufr Aqab, a dense urban neighborhood of tall apartment towers that, like Dahiyat al-Salaam, is cut off from the rest of the city by an Israeli military checkpoint and a gray twenty-six-foot-high concrete wall. To avoid the daily traffic jams and what are sometimes waits of several hours at the Qalandia checkpoint, Atef drove to his work through a far more circuitous route, following the snaking path of the separation barrier.

Atef reported that he was stuck in horrible traffic. It was a wet, gray, and extremely windy February morning in 2012. He said there appeared to be a collision ahead of him, on the road between the Qalandia and Jaba checkpoints. A few minutes after hearing of Atef’s delay, Abed received a call from his nephew: “Did Milad go to the picnic today? There was an accident with a school bus near Jaba.”

II

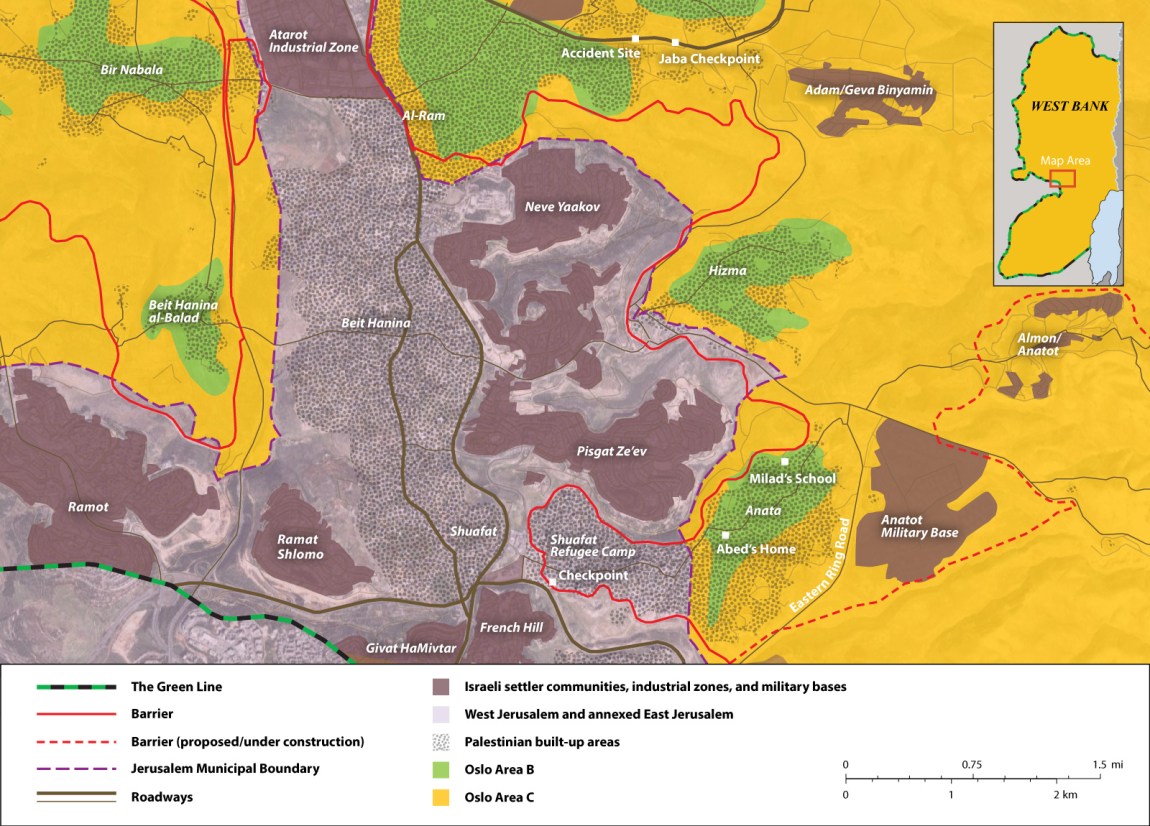

Two and a half weeks after the June 1967 war, Israel annexed what had been Jordanian-controlled Jerusalem and the historic Old City at its core, as well as the lands of more than two dozen surrounding West Bank villages. It declared the entire annexed area to be part of a vastly expanded Jerusalem, that would now stretch from the outskirts of Ramallah in the north to territory within what had been the municipal limits of Bethlehem to the south. Milad and Abed grew up in one of these twenty-eight localities, Anata, but in a part of it that Israel did not formally annex.

Possibly named for the Canaanite goddess Anat or the biblical city Anathoth, the town of Anata was once among the most expansive in the West Bank, stretching eastward from the tree-lined mountains of Jerusalem down to the pale yellow hills, rocky canyons, and desert wadis at the edge of the district of Jericho, in the Jordan Valley. Today, Anata is much smaller, the bulk of its lands confiscated to create the Israeli military base of Anatot, four official settlements, and several unauthorized settler outposts. Abed, like all West Bank Palestinians, is forbidden from entering the settlements, including those built on Anata’s lands. Any Israeli or tourist may enter, but Palestinians require a special permit, granted only to the laborers who clean or do construction or landscaping inside.

Among the settlements on Anata’s lands is Allon, named after the Labor party minister Yigal Allon, architect of the first decade of Israel’s West Bank settlement policy. It lies about eleven miles from Jordan, further east than the West Bank’s nine largest Palestinian cities. A nearby settlement, also on Anata’s lands, is Kfar Adumim, whose notable residents include Israel’s former ambassador to the US, Sallai Meridor, and Danny Tirza, who designed the route of the separation barrier that twists and winds around Palestinian communities in the West Bank, in some cases completely encircling them, as with the rump that remains of Anata.

Kfar Adumim is part of the large Ma’ale Adumim settlement bloc, which includes parks, playgrounds, public schools, health clinics, branches of major banks, a city hall, a police station, a post office, a courthouse, a regional fire station, restaurants, wineries, a bowling alley, an industrial zone with some three hundred businesses, and a cemetery containing the graves of several generations of Israeli citizens. Although the bloc itself is not officially annexed to Israel, Jewish immigrants from Los Angeles or London may move directly to it, or to any other settlement, and receive a basket of government aid that includes free air travel, a financial grant, subsistence allowances for one year, rent subsidies, low-interest mortgages, Hebrew instruction, tuition benefits, tax discounts, and reduced fees at state-recognized day care centers, of which the bloc contains several.

Advertisement

In its guide to communities in Israel, Nefesh B’Nefesh, the main organization partnering with the Israeli government to facilitate Jewish immigration from the US, Canada, and the UK, makes no mention that Ma’ale Adumim is a settlement. Instead, it advertises it as an ideal suburb, “surrounded by palm trees and a breathtaking desert view,” one that offers “all the advantages of a city: an enclosed mall and several strip malls, a municipal government center, intra-city transportation, an extensive library, health services, an art museum, sports and recreational facilities, a lake, a music conservatory, parks and more.”

Not just settlers, but Israelis from all over the country pass through Anata’s lands as they drive to the Dead Sea on Highway 1, Israel’s main east-west thoroughfare. And on weekends and holidays, Israeli families travel to what was once Anata’s natural pool and spring, known as Ayn Fara, but now called the En Prat Nature Reserve. The reserve, managed by the Israel Nature and Parks Authority, lies close to land owned by Abed, which Israel does not allow him to access.

III

On the third morning of the June 1967 war, the day that Israel conquered the West Bank, Defense Minister Moshe Dayan received reports that Palestinian residents were in flight. He ordered the army brigades to slow their advance and keep the roads open, telling Chief of Staff Yitzhak Rabin that the aim was to empty the territory of its inhabitants. Rabin in turn issued orders not to blow up the bridges to Jordan, “in order to ease the emigration” of Palestinians. Psychological operations units of the Intelligence Branch accompanied Israel’s fighting brigades throughout the West Bank, broadcasting messages in Arabic from vehicles equipped with loudspeakers. In Bethlehem, an army van blared commands to residents to take the road to Jericho—the West Bank city adjacent to the main crossing to Jordan and its capital, Amman—“or face the consequences.” Two days later, the threats intensified: Bethlehem residents were told they had “two hours to leave your houses and flee toward Jericho and Amman; if not, your houses will be bombarded.”

In the areas around Jerusalem, Latrun, Hebron, and particularly the West Bank towns near Israel’s pre-1967 armistice line—known as the Green Line, because of the color in which it was drawn on the 1949 armistice maps—thousands of Palestinian homes were dynamited or bulldozed. Standing in Jerusalem at the Western Wall after Israel had conquered it, along with the rest of the Old City, Dayan said, “We have returned to our most holy places; we have returned and we shall never leave them.” Days later, Israel told the residents of Harat al-Magharibah, the Moroccan Quarter, that they had two hours to vacate before their homes, mosques, and landmarks were razed. The neighborhood was flattened and transformed into a prayer plaza next to the Western Wall, in time for the arrival of Jewish pilgrims for the upcoming holiday of Shavuot.

The destruction of these areas and the eviction of their inhabitants were not defensive measures with a military purpose—Dayan admitted that “the Palestinians on the West Bank had not taken part in the war.” Israel’s campaign to clear the land of Palestinians reflected its intention to keep the territory. Abba Eban, Israel’s foreign minister, wrote to Prime Minister Levi Eshkol that “we had been fortunate with the flight of 350,000 [people] from the administered territories.” The commanding general in the West Bank, Major General Uzi Narkiss, recalled that “we certainly hoped that [the population] would flee, as in 1948.”

Yet the removal of Palestinians in 1967 was not as comprehensive as it was during the 1948 war, when four out of five Palestinian inhabitants of the territory that would become Israel were made refugees and were banned from returning to their homes. A Palestinian majority became a minority within the Green Line. During the 1967 war and its immediate aftermath, the portion of Palestinian residents exiled from the newly occupied territories was considerably smaller—about one in four. As a consequence, the share of Palestinians living under Israeli rule increased, rising from 14 percent before 1967 to 37 percent afterward. Israel became a state of 2.4 million Jews controlling 1.4 million Palestinians: one million in Gaza, East Jerusalem, and the rest of the West Bank, plus nearly 400,000 non-Jewish citizens within the Green Line, most of them Palestinian. Eshkol summarized Israel’s strategic dilemma with a line that he often repeated: “We won the war and received a nice dowry of territory, but along with a bride whom we don’t like.”

Advertisement

Efforts to rid the land of its Palestinian inhabitants continued after the war. The prime minister established a secret unit dedicated to encouraging Arab emigration. During the first days of the occupation, the Arabic service of Israel’s state radio, Kol Yisrael, announced that “any inhabitant of the West Bank area living in Jerusalem and its surroundings” could cross to Jordan. Buses bearing Arabic signs that read “To Amman for free” transported frightened and in many cases homeless Palestinians to Jordan. Major General Chaim Herzog—a future president of Israel, the brother-in-law of Abba Eban, and the West Bank’s first military governor—later boasted that, as a result of these efforts, “approximately 100,000 people crossed over to the East Bank.”

During a postwar cabinet discussion on the Palestinians fleeing the occupied territories, Dayan said, “I hope they all go.” He also predicted that “in two days’ time, the whole of Jerusalem will become Jewish.” He reported that some four hundred Palestinians from the West Bank and six hundred from Jerusalem were leaving each day. “It adds up to approximately one thousand a day,” he said. “This is terrific.”

Under direction from Dayan and the cabinet, Israel initially banned the return of Palestinians who had crossed to Jordan. But the month after the war, hoping to thwart a UN resolution demanding an immediate and unconditional withdrawal from the occupied territories, Israel caved to mounting international pressure by agreeing to let some Palestinians return. Prime Minister Eshkol voted against the decision, a stance he later explained, revealingly, by referring to the West Bank as part of the country: “We cannot increase the Arab population in Israel.” The state let in only a negligible number of those who applied, vetoing the return of most residents from Jerusalem, Bethlehem, Jericho, and the West Bank camps that housed refugees of the 1948 war, now displaced once again. It offered a mere twelve-day window for hundreds of thousands to return, stating that it could take in no more than 3,000 refugees per day—a total of 36,000—and in the end it accepted far fewer: 14,000, which was less than the number of Palestinians crossing that month in the opposite direction. In later years, when Palestinians who had fled in 1967 applied to reunite with their family members in the West Bank, Israel barred large categories of people: men aged sixteen to sixty; the twice-exiled refugees of both the 1967 and 1948 wars, whose original claims to return still nettled Israel; former residents of Jerusalem; and landowners, because there were plans to build settlements on West Bank property that Israel defined as “abandoned.”

In Gaza, Israel was intent on removing Palestinians from the territory in order to annex it. Future prime minister Golda Meir, then the head of Mapai, the precursor of the Labor party, said Israel should retain Gaza while “getting rid of its Arabs.” Minister of Labor Yigal Allon said, “I am prepared to encourage emigration of non-Jews in general.” Israel forcibly expelled three thousand people from Gaza in the weeks after the war. Tens of thousands more left in the year after, some of them taking Israeli financial incentives to emigrate to South America. Prime Minister Eshkol expressed hope that, “precisely because of the suffocation and imprisonment there, maybe the Arabs will move from the Gaza Strip.” He added, “Perhaps if we don’t give them enough water they won’t have a choice, because the orchards will yellow and wither.” Even the Palestinian citizens of Israel were not spared from these schemes: at a 1967 cabinet meeting, Minister Allon recommended “thinning the Galilee [inside the Green Line] of Arabs.”

On October 13, 1967, the cabinet approved a set of “Operational Principles for the Administered Territories.” These prescribed “the departure of a maximum number of Arabs,” while “blocking the entry of Arabs from the outside”; required that “special emphasis is to be placed on the evacuation of the Gaza Strip”; and noted that “the imposition of the Israeli tax system in the territories could play a significant role in encouraging departure across the borders.”

Ultimately, however, none of these policies could overcome the combination of Palestinians’ determination to stay on the land, known as sumoud, and birth rates that were far higher than those of Israeli Jews. In October 1968, Eshkol said of the Palestinians in Gaza, “I still don’t know how to get rid of them.” Not even the more than one million new immigrants from the Soviet Union and its successor states in the 1990s and 2000s could stem the loss of a Jewish majority. By 2018, the fifty-first year of the occupation, an army official reported to Israel’s legislature, the Knesset, that there were more Palestinians than Jews in the territory under Israel’s control, from the Mediterranean coast to the Jordan River.

For over half a century, Israel’s strategic dilemma has been its inability to erase the Palestinians, on one hand, and its unwillingness to grant them civil and political rights, on the other. Explaining his opposition to giving Palestinians in the West Bank the same rights as Palestinian citizens of Israel, Abba Eban said that there was a limit to the amount of arsenic the human body could absorb. Between the two poles of mass expulsion and political inclusion, the unhappy compromise Israel found was to fragment the Palestinian population, ensuring that its scattered pieces could not organize as one national collective.

Administratively, fragmentation was implemented by imposing varying restrictions, decrees, or laws on Palestinian residents of the different sub-units Israel defined for them: Gaza; the West Bank; East Jerusalem; Israel within the Green Line; and refugees outside the state. Nowhere were Palestinians granted rights equal to those of Jews. Physically, fragmentation was achieved through the establishment of Israeli settlements and their surrounding roads, national parks, archaeological sites, and closed military zones, which left Palestinian communities isolated from one another and surrounded by fences, walls, checkpoints, closed gates, roadblocks, trenches, and bypass roads.

IV

Nader Morrar grew up in the West Bank village of Beit Duqqu, north of Jerusalem. His family arrived there after the 1948 war, when the Israeli army assaulted their village of Salbit, now Sha’alvim, a Jewish religious kibbutz in central Israel. Beit Duqqu sits within a confined enclave of eight villages, walled off from surrounding West Bank towns, Israel within the Green Line, annexed East Jerusalem, and the large Israeli settlement of Givat Ze’ev, which is built partly on Beit Duqqu’s land. The separation barrier encloses the enclave on three sides. A fourth side is blocked by a fenced West Bank highway, Route 443, built for settlers and other Israeli citizens and effectively closed off to most Palestinians. It serves as the shorter of two main routes from Jerusalem to Israel’s international airport, which West Bank Palestinians cannot use.

At the height of the Second Intifada, the 2000–2005 Palestinian uprising against Israel, when more than a thousand Israelis and three thousand Palestinians were killed, Nader was a student at the West Bank’s top university, Birzeit, studying English literature. Israel had shut the main road to the school, preventing thousands of students and hundreds of faculty members from entering it. At a student protest calling for the school to be opened, an Israeli soldier shot Nader in the leg, fracturing his femur. It took him two surgeries and a year of rehabilitation to recover. He dropped out of school. Inspired by those who had cared for him, he enrolled in courses to become a paramedic.

A decade later, working as an emergency medical technician for the Palestine Red Crescent, he was shot in the leg by Israeli forces once again. During the past two decades, Israeli soldiers have injured hundreds of members of Palestinian emergency medical teams, killing several. The day before the school bus accident in Jaba, two Red Crescent ambulances had been attacked by the Israeli army, one of them hit with rubber-coated bullets near the Ofer Prison, between Ramallah and Givat Ze’ev, the other struck at a protest in the Jerusalem neighborhood of Issawiya, which sits on the slope beneath Hadassah Hospital at Mount Scopus, facing Milad and Abed’s home in the Anata enclave.

On the morning of the crash, Nader received a call from dispatch at 8:54 AM: a bus had rolled over on the road leading to the Jaba checkpoint. The caller did not say if the bus was empty or full. Nader knew the accident site, which some referred to as the death road. Originally built for settlers to get to Jerusalem without driving through Ramallah, it had been carved straight through an escarpment, forming a deep chasm, with tall rocky walls on both sides, dozens of feet high. At the time it had two lanes heading northwest toward the Qalandia checkpoint, and only one lane in the opposite direction, which was the main route around Jerusalem to the southern West Bank for some 200,000 people in the greater Ramallah area. The road had no center divider. Frustrated southbound drivers, having finally escaped the maddening gridlock at the Qalandia checkpoint, would often overtake slower vehicles by veering momentarily into one of the two lanes of opposing traffic.

Nader assumed Israeli ambulances would arrive there first. He was stationed at the Red Crescent headquarters, downhill from the entrance to the al-Amari refugee camp in al-Bireh, next to Ramallah. To get to the accident site at rush hour, he would have to drive south through al-Bireh, into the municipal Jerusalem neighborhood of Kufr Aqab, past the standstill traffic near the Qalandia checkpoint, and then through the pile-up on the single southbound lane leading to the accident, a distance of about four miles. It was a wet, windy morning, with poor visibility. Nader wondered how quickly he could get there via the dilapidated roads in Kufr Aqab, which often flood, worsening congestion.

To his surprise, he made it in ten minutes, arriving at 9:04. He and his partner, who drove the ambulance, were the first emergency responders to get there. Nader was shocked by what he saw. Crowds stood above him on the tops of the stone cliffs overlooking the road, waving their arms and shouting. In front of him, a damaged twelve-wheel trailer truck had come to a diagonal halt in the northbound lanes, facing the wrong direction. To his left, against the stony northbound wall, lay a school bus, flipped on its side, doors against the ground, crumpled in front, and engulfed in flames. Nader was thirty-three years old at the time. His wife was six months pregnant, and his eldest daughter not yet two. Screams of children and teachers came from inside the bus. Men darted in and out of the smoke, putting themselves at enormous risk to pull people from the flames. Several charred bodies lay in the road. Nader radioed in to headquarters, calling for backup: “Mass casualty incident.”

A video taken that morning shows the scene before Nader arrived. Dozens of people gather around the overturned bus, which is taller than all of them, with red flames shooting into the air and thick black smoke rising above the rocky wall. A woman is heard shrieking from inside the bus. “There are kids inside,” someone yells. “Extinguishers! Extinguishers! Extinguishers!” Men rush forward with small fire extinguishers taken from their cars. Others bring plastic bottles, helplessly pouring them onto the blaze. The flames continue to grow. A man paces desperately in a circle, gripping his face with both hands. Another hits himself on the head. A third, his small fire extinguisher emptied, storms away from the bus, yelling, “Where are you people?! Dear God!” as he raises the extinguisher over his head and slams it to the ground. A small blackened corpse lies on its back in the middle of the road. “Cover him, cover him,” one man tells another. “Where are the ambulances?!” someone else yells. “Where are the Jews?” Two men run forward holding a child between them: “The boy is alive. He needs resuscitation quickly.” Someone points to an adult on the ground: “Bring a car. This man is alive.” A blurry figure jogs from near the bus carrying a kindergartner, her hair in braids fastened with pink ties. She seems to be unhurt and in a kind of dream state, not responding when he sets her down and asks, “Do you need anything, dear?” Other men start to bring more children, one by one. They are put in private cars to take them to the hospital. The wailing from inside the burning bus continues.

As soon as Nader got out of the ambulance, people tried to hand him the corpses. By this point, the fire was so intense that there was no way to approach the bus and rescue the remaining students and teachers inside. He saw two adults lying on the asphalt, each with third-degree burns, major fluid loss, and difficulty breathing. One was the bus driver, who had multiple fractures to his lower limbs; the other was a teacher. Nader and the ambulance driver performed triage and loaded them on to the ambulance for immediate evacuation. For Nader, there was no question but that he would take them back to Ramallah, though they were less than a mile from municipal Jerusalem, which had superior hospitals. Palestinian ambulances bringing patients to Jerusalem had to wait at the checkpoints for unpredictable lengths of time before permission was granted, or denied, to carry the victim on a stretcher to an Israeli ambulance on the other side. Scores of people have died, according to Amnesty International, B’Tselem, and other human rights organizations, because the passage of Palestinian ambulances was prevented or delayed.

For Nader, in a crisis, the separate legal statuses of Palestinian citizens of Israel, Palestinian subjects of Israeli military rule, and Palestinian permanent residents of annexed East Jerusalem no longer mattered. This was an accident between a yellow-plated Israeli tractor trailer and a green-plated Palestinian school bus with many permanent residents of Jerusalem on board, yet Nader knew that the only thing that mattered was whether the patients were Palestinians or Jews. Under no circumstance would he bring a Jewish citizen to a Palestinian hospital. But in order to avoid delays at checkpoints, he had brought numerous Palestinians with Israeli citizenship to West Bank hospitals—and for all he knew, he was now carrying two more. As they rushed back toward the medical center in Ramallah, passing next to the Qalandia checkpoint with sirens blaring, Nader treated the teacher and bus driver simultaneously, giving oxygen and stemming the loss of fluid. “I still hear their screams,” he told me.

Nader learned later that he hadn’t arrived on the scene until twenty-nine minutes after the 8:35 AM crash. The first call to dispatch hadn’t come until nineteen minutes after the accident, at 8:54. The crash was so close to the checkpoint, nearby settlements, and Jerusalem that it didn’t occur to any of the bystanders that Israeli ambulances, fire trucks, police, and soldiers were not on their way. The crash involved an Israeli trailer truck and had occurred in Area C, the 61 percent of the West Bank that is under full Israeli civil and security control. Every settlement and road serving settlers in the West Bank is in Area C, which is a single contiguous territory. On Area C roads, which are formally under military occupation but have been de facto annexed by Israel, the Israeli national police—not the army—hand out tens of thousands of traffic tickets to Palestinians each year. The Palestinian police are not allowed even to drive on Area C roads without Israeli permission, typically requested days in advance. For Israel’s National Fire and Rescue Authority, not just Area C but the entirety of the West Bank is treated as being within the sovereign state of Israel, its website listing the regional fire stations responsible for “all localities throughout the country,” from Jaffa to Jaba to Jericho.

A Palestinian Authority report on the accident notes that “Israeli ambulances and fire engines arrived late, after the end of fire and rescue operations, and this despite the proximity of the accident site to Israeli fire and rescue services, as the nearest Israeli ambulance, emergency and fire station is only a minute and a half away.” The accident site was seconds away from the Jaba checkpoint, manned by Israeli soldiers, less than a two-minute drive to the settlement of Adam, and several minutes from both the police station at the Sha’ar Binyamin settlement industrial zone and rescue services at the settlement of Kokhav Ya’akov.

The fact that the driver of the tractor trailer was an Israeli permanent resident operating an Israeli-registered vehicle, violating Israeli traffic laws by crossing a double line into opposing traffic, and striking the bus in a location that is under full Israeli control, where Palestinian Authority vehicles require permission to enter, “places a moral and legal responsibility on the Israeli side,” according to the Palestinian Authority report. It further states that rescue operations were impeded by the “suffocating traffic” caused by the Israeli checkpoints on both ends of the road, and that previous Palestinian requests to install lighting and a concrete barrier between opposing lanes had been “rejected by the Israeli side.”

V

Abed and Milad’s house lies within an area that is surrounded on three sides by the towering concrete slabs of the separation barrier. On the fourth side is a different sort of wall, made of yellow stone and topped by a tall metal fence. It runs through the center of a four-lane highway, a section of the Eastern Ring Road that is widely known as the “apartheid road,” which forms what is now the eastern border of Anata. On one side of the highway, Israeli drivers, most of them traveling to and from West Bank settlements, overlook an eastward view of the rolling hills of their biblical patrimony. On the other side, Palestinian drivers, forbidden from entering Jerusalem and walled off from the view of Israelis on the other side of the road, look west toward the Anata enclosure, in front of which lie heaps of old cars, stripped and abandoned.

Within these walls are also several neighborhoods of municipal Jerusalem: Ras Khamis, Ras Shehadeh, the Shuafat Refugee Camp, and the part of Anata known as Dahiyat al-Salaam. Their residents pay taxes to the city but receive almost no services. Sewage runs through the streets. Roads are unpaved and potholed, lacking lanes, traffic lights, parking places, pedestrian crossings, and sidewalks. There are no parks or playgrounds. Piles of garbage rot beside the separation wall. Because of inadequate municipal collection, several tons of trash are burned within the Shuafat-Anata enclave each day, releasing dangerous emissions. Israeli ambulances, fire engines, and other basic service providers do not enter without a military escort. The Border Police, which fights alongside the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) in the occupied territories, drives into the area in armored vehicles, carrying assault rifles and wearing shielded helmets, kneepads, and body armor. “The Jerusalem Police did not operate in the east of the city”—that is, in all Palestinian areas, not just the neighborhoods separated by the wall—“as a traditional policing force,” said Arieh Amit, the former police commander of the Jerusalem district, in 2001. “Its operations were based on the model of a small army, and it saw its principle function as being to protect from the residents of the east of the city, rather than to protect them.” A decade later, another former police commander of the Jerusalem district, Mickey Levy, said of the Palestinian neighborhoods, “We have no need for them.” Unlike the Border Police gendarmerie, “the Israel Police doesn’t go in there.” This is still the case today.

Nearly all of the dead and most severely injured on Milad’s bus were from the Shuafat Refugee Camp and its outgrowths, within the western half of the Shuafat-Anata enclave that is part of annexed municipal Jerusalem. The infrastructure of the camp and its surrounding neighborhoods is collapsing. Power outages are frequent. In 2014, tens of thousands of residents were left without any water for several weeks. The area is so neglected that Israel does not know how many people inhabit it. The Association for Civil Rights in Israel estimated that the half of the enclave that is within municipal Jerusalem had 80,000 residents in 2019, equivalent to one fourth of Jerusalem’s Palestinian population. They live within a municipal area of less than half a square mile—more than double the population density of Manhattan—in a concrete jungle of dilapidated, unplanned, and unregulated buildings.

There are only two exits from the enclave, which slopes downhill from Shuafat camp to Anata. One exit, which leads into the rest of the West Bank, is at the bottom of the hill, next to the entrance to the “apartheid road.” The other, which leads into the rest of Jerusalem, is a traffic-clogged military checkpoint at the walled entrance to the Shuafat camp. Most checkpoints are either internal, controlling Palestinian movement within the West Bank, or external, controlling Palestinian exits from and entrances to Gaza and the West Bank. The Shuafat checkpoint, which is staffed by IDF soldiers, Border Police, and private security guards, is neither: it controls the movement of tens of thousands of Palestinian residents of Jerusalem, who line up each morning to cross through metal turnstiles separating one part of the city from another, all within what Israel considers its sovereign capital.

Most residents of Shuafat camp work in Jerusalem on the other side of the wall, some of them as pharmacists, nurses, cooks, and cleaners in the now-Jewish neighborhoods from which their families fled or were expelled in 1948. A number of Shuafat’s families come from the Jerusalem neighborhood of Qatamon, a prosperous, mostly Christian neighborhood that they fled after the Haganah, the main pre-state Zionist militia, blew up the Semiramis Hotel in January 1948, killing twenty-six civilians. They were among the 250,000-300,000 Palestinians who were made refugees before May 14, 1948, when Israel declared independence and Arab armies invaded; over the following months, another half million Palestinians became refugees. Some of their grandchildren and great-grandchildren now throw Molotov cocktails and colored paint at the soot-covered Israeli watchtower that looms over the high walls of the Shuafat-Anata enclave. Also overlooking this ghetto, within eyesight, are the manicured grounds of the Hebrew University, one of Israel’s most prestigious academic institutions.

Like all Palestinians legally present in the occupied territories, Abed was issued a unique ID number registered by Israel’s army and Interior Ministry. Without that number and accompanying Israeli ID card, a Palestinian cannot cross a checkpoint, open a bank account in Ramallah, or leave the occupied territories. In Gaza, where two million people live among ponds of sewage, without drinkable water or regular electricity, every inhabitant must be registered with an Israeli ID number in order to gain permission to leave the territory. Such permission is granted to very few—mostly businessmen and medical patients in need of care unavailable in the impoverished coastal strip. Despite Israel’s claim to have ended its occupation of Gaza, tens of thousands of people are stranded there because they lack an Israeli ID number—many of them children of Palestinians who entered on tourist visas—and consequently are unable to leave under any circumstances, even at the border with Egypt. Thousands of others from Gaza now live in the West Bank under threat of deportation because Israel has not approved their relocation from one part of the occupied territory to another.

Inside the Shuafat-Anata enclosure, Abed could move around without needing to worry about whether, at any given moment, he was crossing from the West Bank into annexed East Jerusalem. As they bought picnic treats in Dahiyat al-Salaam, which is the annexed part of Anata, he and Milad were, technically, “illegal infiltrators” to Israel, even though they were simply walking inside the town in which Abed, his parents, and his grandparents were born and raised. Abed and his wife hold the green ID cards issued to Palestinians in Gaza and the unannexed areas of the West Bank. Some of their relatives, like Abed’s cousins, have blue ID cards, indicating that they are residents of Jerusalem, who may vote in Israeli municipal but not in national elections. Palestinians from one part of Anata, with green IDs, have been arrested for working without permits in another part of Anata, in municipal Jerusalem. But no barrier exists between annexed Dahiyat al-Salaam and unannexed Anata. To determine where one ends and another begins, you would have to find the last building affixed with a small blue and white address plaque, written in both Arabic and Hebrew.

As a young man, Abed’s brother, who held a green ID, married a young woman with a blue ID. Like all such couples, they were forbidden from residing together in municipal Jerusalem, unless they took their chances by living illegally in one of the distressed Jerusalem enclaves cut off from the rest of the city by the wall. His wife could not legally bring her husband to Jerusalem until he turned thirty-five and was eligible to apply for a temporary Jerusalem residence permit, which must be renewed annually and does not confer the health or national insurance benefits of a blue ID. She could have applied for Israeli citizenship, which would allow her to live with her husband in Anata, but the process is lengthy and cumbersome, and the rate of rejection is high. It is also a politically fraught act because it is seen as conferring recognition on Israel’s annexation of East Jerusalem. Neither would it solve her fundamental problem, since by law Israeli citizens, too, may not obtain citizenship for their spouses residing in the occupied territories, unless the spouse is Jewish. When presented with challenges to this law, which discriminates between citizens on the basis of their ethnicity, in order to reduce the population of Palestinians in Israel, the Supreme Court rejected the petitions in 2006 and 2012. In the court’s 2012 ruling, its deputy president wrote, “Human rights are not a recipe for national suicide.”

Abed’s sister-in-law could not move out of municipal Jerusalem herself, even to an unannexed area just nearby, such as the eastern half of the Shuafat-Anata enclave. If she did, Israel could revoke her blue Jerusalem ID, forever exiling her from the city in which she grew up and where her family resides. As it was, inspectors from Israel’s national insurance provider, accompanied by private security contractors, regularly visited her apartment in Dahiyat al-Salaam, to demand proof that the residence was indeed her “center of life.” Such inspectors often arrive in the middle of the night, aiming to prove that blue ID holders have left the city, typically for nearby towns in the West Bank. By imposing onerous conditions on the city’s residents and monitoring any relocation outside it, Israel has managed to strip nearly 15,000 Palestinians of their right to reside in Jerusalem. In the West Bank and Gaza, Israel has exiled an additional 240,000 former residents, many of them for being absent during a given Israeli-conducted census or for having left to study or work abroad.

Israel’s revocation of Palestinian residency rights in Jerusalem is part of a broader strategy of pushing Palestinians out. In 1973, a ministerial committee recommended that the government maintain the existing “demographic balance” in Jerusalem at that time: 73.5 percent Jews and 26.5 percent Palestinians. Israel failed to meet its target, subsequently amending the desired Jewish-to-Palestinian ratio to 70:30, and then to 60:40. The current master plan guiding municipal policy in Jerusalem, the Jerusalem 2000 Outline Plan, warns that “the continued proportional growth of the Arab population in Jerusalem is bound to reduce the ratio of the Jewish population in the future” and calls “to prevent such scenarios, or even worse, from taking place.”

As the share of Palestinians in Jerusalem has grown, so has the pressure placed on them to leave. The primary lever has been housing policy. Since 1967, the Israeli government has initiated the planning and construction of more than 55,000 housing units in East Jerusalem settlements, whose residents now make up 24 percent of the city’s overall population. By contrast, in Palestinian neighborhoods of East Jerusalem, whose residents make up nearly 40 percent of the city’s population, the government has initiated the construction of six hundred. Due to discriminatory planning, Palestinians are forced either to move to the West Bank or to build without permits. As a result, more than a third of the city’s Palestinian homes were built without permits, putting some 100,000 people under threat of eviction and home demolition. More than 2,500 Palestinians in East Jerusalem have had their homes pulverized in the last decade, hundreds of them forced to destroy their own homes in order to avoid paying heavy fines.

Another lever has been the neglect of Palestinian infrastructure. Many neighborhoods in East Jerusalem have roads too narrow for municipal garbage trucks, creating filthy streets and smoke from trash burning on the hillsides. These neighborhoods exist as small islands, surrounded by major traffic arteries designed to connect the city’s Jewish neighborhoods, which are mostly served by separate bus lines. The main north-south thoroughfare for Palestinians in East Jerusalem, the old Bethlehem Road, is just wide enough for one vehicle in each direction, at least on the parts of it with no cars parked on the side. It is steep and dangerous, with hairpin turns, few guardrails or sidewalks, and no lanes, traffic lights, streetlights, or pedestrian crossings. The main north-south artery serving West Jerusalem, the four- to six-lane Begin Highway, was recently extended, seamlessly connecting the settlements south of Bethlehem to the Jerusalem city center and beyond. The expansion was built on lands expropriated from the annexed Palestinian neighborhoods of Sharafat and Beit Safafa, both of which the highway cuts in half.

A third lever has been discriminatory policy in education. The shortage of classrooms in Palestinian neighborhoods is severe. Fewer than half the Palestinian students are able to attend public schools. A third of Palestinian students—compared with 1.5 percent of Jewish students—drop out. In the western half of the Shuafat-Anata enclave, which is within municipal Jerusalem and is home to some 80,000 residents, the municipality has built only one school, in a former goat pen. Lacking access to adequate public education, many parents in the enclave are forced to enroll their kids in private schools. One of these was Milad’s, Nour al-Houda. It is within the enclave but outside the Jerusalem municipal lines, in one of the buildings most closely abutting the wall. On the other side of the separation barrier, a few hundred yards away, stand the red-roofed garden villas of the Jerusalem settlement of Pisgat Ze’ev.

VI

As soon as Abed got the call about the accident, he and his cousin rushed out of Atef’s butcher’s shop, heading to Jaba. Abed’s cousin drove them through morning traffic toward Anata’s only exit, past the teenage boys starting work in the car-repair garages with signs in Hebrew for settler customers, past the Nour al-Houda school and the separation wall beside it, and onto the road leading to the Hizma checkpoint, the main one used by settlers entering Jerusalem from the north. The road hugs the wall at the Palestinian village of Hizma, then climbs the steep hill to the settlement officially called Geva Binyamin but known locally as Adam—which happens also to be the name of Milad’s older brother.

At the Adam settlement junction, soldiers were stopping traffic from driving toward the accident site. Abed left his cousin and hurried ahead on foot. He hailed a passing army jeep, saying that his son was in the bus accident and asking for a lift. The soldiers refused.

By the time Abed reached the site of the crash, Nader was long gone. Abed couldn’t see the bus at first, his view blocked by the twelve-wheel tractor trailer standing crookedly across the lanes. There were dozens of people on the road, including other parents who had rushed to the scene.

“Where is the bus?” Abed asked. “Where are the kids?” A moment later, he saw it, tipped over, burned out, and empty. Israeli ambulances and fire trucks still had not arrived. Later that day, the head of the Jerusalem office of ZAKA, an Israeli emergency response organization, explained the delay: his teams, which first had “to get the necessary permits,” had trouble finding the scene because it was close to Palestinian villages, with which they were unfamiliar.

Rumors swirled around Abed, passing from one onlooker to another: the kindergarteners were taken to a health clinic in al-Ram, two minutes up the road; they were at the Israeli military base at the entrance to al-Ram; they were at the medical center in Ramallah; they had been transferred from Ramallah to the Hadassah hospital at Mount Scopus in Jerusalem. Abed had to decide where to go. With his green ID, he had no way to enter Jerusalem. The rumor about al-Ram seemed unlikely, given that it had no hospital. He asked two strangers for a ride to Ramallah. They were headed in the opposite direction, having just traveled two and a half hours south from Jenin. They agreed without hesitation.

It was a scene of chaos at the Ramallah hospital, a maelstrom of shouting parents, victims on stretchers, medical staff, police, photographers, television crews, and Palestinian officials. Abed made his way to the reception desk and gave Milad’s name. “Your child is registered on the second bus,” he was told over the din. “That one wasn’t in the accident. They took it to al-Ram.” This was the first Abed had heard of a second bus. He called a friend whose child was in Milad’s class, asking him to check with his wife, a teacher at the school. She called back right away: “Milad is registered on the second bus. He’s fine.”

VII

The West Bank is often described as a lawless frontier territory, where rogue Jewish fanatics haphazardly park mobile caravans on hilltops, in defiance of the Israeli state. In fact, the entire map of West Bank settlements has been meticulously planned by the Israeli government. An executive branch ministerial committee approves the settlements. A legislative branch subcommittee is devoted to advancing their connections to Israel’s water, electrical, sewage, communications, and road infrastructure. The legislature passes certain bills that apply solely to the West Bank. The state comptroller supervises government policy in the West Bank, overseeing everything from wastewater pollution to road safety. The attorney general enforces guidelines that direct the Knesset to explain how every new bill passing through the legislature will apply to the settlements. The High Court of Justice—which exercises judicial review over all government bodies and agents, and is the court of last instance for every Israeli and Palestinian, whether citizen or occupied subject—issues rulings that entrench the segregated legal system in the West Bank, where, in the same territory, there is one set of laws and rights for Israeli settlers and another, inferior set for Palestinians. The Justice Ministry oversees local courts in the West Bank that apply Israeli laws to settlers but not to Palestinians. The Israel Prison Service extends its reach across the entire territory, holding both Palestinian subjects and Israeli settlers in jails within the Green Line.

As for the settlements themselves, they are integrated into Israel’s system of local government, forming cities, regional councils, and local councils under the authority of the Ministry of Interior. And Israel’s ministries—housing, education, economy, interior, agriculture, water, and transportation—spend hundreds of millions of dollars per year on developing the settlements. Far from being the enterprise of a small minority of settler ideologues, Israel’s absorption of the West Bank is a national project undertaken by every branch of the government.

There have been four major plans for Israeli settlements in the West Bank since 1967. They share a few basic principles. Each one sought to expand Jewish settlement; encircle the Palestinian population by solidifying Israel’s presence in the Jordan Valley; fragment Palestinian communities within the encircled territory; prioritize settlement in the greater Jerusalem area, in order to sever Palestinian East Jerusalem from the rest of the West Bank; and, with the exception of the two holiest cities of Hebron and Jerusalem, avoid planting settlements in densely populated Palestinian areas. In their main objectives, these plans have succeeded.

The first of the four plans, the Allon Plan, named after Yigal Allon, the former minister of labor who also served as chairman of the Ministerial Committee for Settlement, was never formally adopted but it did serve as guidance for government settlement policy from 1967 to 1977. It was the only settlement plan that simultaneously served as an Israeli peace proposal, though not one that had any chance of success. It called for Israel to annex a third of the West Bank along its eastern border, as well as an east-west strip in the narrow center of its kidney-shaped territory, leaving two, disconnected northern and southern cantons for the Palestinians, each one surrounded on all sides by Israeli territory. Israel later proposed that Jordan take over these cantons, which would be connected to Amman by a narrow corridor. Allon himself admitted that, as a peace proposal, it was a ruse: “No Arab would ever accept the plan and nothing will come of it, but we must appear before the world with a positive plan.” The lines of the proposed partition plan did not constrain its architect: Allon promoted Jewish settlement not only within the areas his plan allotted to Israel, but also inside those designated for the Palestinians, such as Hebron.

By the time the right-wing Likud party came to power, in May 1977, the governments led by the center-left Israeli Labor party and its predecessors had established forty-eight settlements in the occupied West Bank and East Jerusalem, mostly in the areas that Israel planned to annex according to the Allon plan.

The next plan was developed in 1977 by a subsequent chairman of the Ministerial Committee for Settlement, Ariel Sharon. It built on Allon’s plan, though Sharon promised that the settlements “will be more extensive than in the past”—a pledge on which he delivered. Sharon’s primary innovation was to add a new east-west line of settlements that would split the West Bank into not two, but three Palestinian cantons, while simultaneously adding a north-south strip of settlements inside one of them. Sharon said his goal was to insert a wedge of Jewish settlement between the large northern West Bank cities and those Palestinian citizens of Israel who lived in dense concentrations near the Green Line, so as to prevent Palestinians in Israel and in the West Bank from developing into a “solid Arab bloc.” Within the Green Line, too, Sharon-era settlement policy aimed to increase the proportion of Jews and reduce that of Palestinians. Describing plans for an area within the Green Line, Raanan Weitz, then the head of the World Zionist Organization’s settlement division, which is funded by the state and implements its policy, said: “In Galilee, our solution must be to have a preponderance of Jews, with a very small Arab minority.”

The third plan arrived a year later. Written by the joint head of the World Zionist Organization settlement division, Matityahu Drobles, it was essentially a more detailed version of the Sharon plan, further fragmenting Palestinian areas of the West Bank, referred to by the Israeli government as Judea and Samaria. Among its chief aims were to obliterate the Green Line by creating new Jewish settlements on either side of it, and to deploy Jewish settlements “not only around” Palestinian communities, but also as wedges “among them, in accordance with the settlement policy adopted in the Galilee” (within the Green Line). The plan explained the purpose of these wedges thus:

To minimize the danger of the development of an additional Arab state in this territory. Since it will be cut off by Jewish settlements, it will be hard for the minority population to create territorial contiguity and political unity. There mustn’t be even the shadow of a doubt about our intention to keep the territories of Judea and Samaria for good. Otherwise, the minority population may get into a state of growing disquiet which will eventually result in recurrent efforts to establish an additional Arab state in these territories. The best and most effective way of removing every shadow of a doubt about our intention to hold on to Judea and Samaria forever is by speeding up the settlement momentum in these territories.

The Drobles plan, updated in 1980, was implemented by the Israeli government, even as it was negotiating with Egypt over a possible arrangement to grant the Palestinians limited autonomy under Israeli rule. At that time, the Palestinians categorically rejected limited autonomy. But a little over a decade later, when their leadership was internationally isolated, financially depleted, thinned out by Israeli assassinations, and operating from exile in far-away Tunis, they accepted it.

For its part, Israel wanted to stop having to police Palestinian cities. It was exhausted from more than five years of combatting a Palestinian popular uprising, the First Intifada. That revolt began with unarmed protests, shop closures, labor strikes, and consumer boycotts, but by its final years, the popular movement had petered out, giving way to the Intifada’s most violent period. In response, Israel imposed a closure on the West Bank and Gaza beginning in March 1993, while its security chiefs urged the government to find a political solution. The prime minister authorized Israeli officials to pursue secret talks with Palestinian representatives, whom Israel urged, through to the final negotiating session, to find a way to stop the uprising. The resulting autonomy agreements—the September 1993 Oslo Accord and its offshoots—established the Palestinian Authority; they still dictate its responsibilities and areas of operation to this day.

By the time of Oslo, there were more than a quarter million settlers, including 111,000 in 120 West Bank settlements and 152,000 in a dozen settlements in East Jerusalem. The Oslo map was guided by two central principles: first, not a single settlement would be removed; second, Israelis would have territorial contiguity and the Palestinians would not. As a result, the Oslo map looks nearly identical to the Drobles map—except as a photo negative: whereas the Drobles map had the West Bank as a Palestinian kidney covered with twenty-two amoeba-shaped settlement blocs, the Oslo map, in order to make the blocs contiguous, turned the West Bank into an Israeli kidney dappled with 165 islands of Palestinian autonomy.

The land of the Palestinian islands was divided into two types: the areas Israel was most eager to stop policing, the city centers, were categorized Area A; together, its disconnected parts make up 18 percent of the West Bank. Here, the Palestinian Authority administers most civil affairs and internal security, although Israeli forces are still present not just around but inside it every day. Palestinians have no judicial authority over Israelis anywhere in the occupied territories, including in Area A, where Israeli forces can and do arrest Palestinians at will, including for crimes such as car theft. Area B islands, which contain Palestinian towns and villages, make up another 21 percent of the West Bank. Here, Israel is in charge of security and the Palestinian Authority handles civil matters like health and education.

The remaining 61 percent of the West Bank—in effect, the sea in which the Area A and B islands float—is annexed East Jerusalem and Area C, where Israel controls both security and civil affairs related to territory, including land allocation, planning, building, and infrastructure. Outside annexed East Jerusalem, every West Bank settlement, settler bypass road, national park, and military base is in Area C. In total, Area C, annexed East Jerusalem, the no man’s land near Latrun, and Green Line Israel constitute 91 percent of the land area of Israel-Palestine, excluding the annexed Golan Heights. The areas of limited Palestinian autonomy, in Gaza and the West Bank, make up the remaining 9 percent.

There are roughly 300,000 Palestinians and more than 475,000 Israeli Jews living in Area C. Palestinians may legally apply to build only in communities for which Israel has approved a master plan, which is a rare occurrence. Lacking master plans in some 90 percent of their communities in Area C, Palestinians can apply to build legally in less than 1 percent of that area. Even within that 1 percent, Palestinians almost never receive the permits they request. From 2000 to 2020, according to official Israeli figures, Israel rejected more than 96 percent of Palestinian building permit applications. During the same period, Israel demolished thousands of Palestinian housing units, leaving some 10,000 people homeless. Meanwhile, tens of thousands of West Bank housing units were built for Israeli Jews. Of the public lands in the West Bank that Israel has allocated for any kind of use, approximately one quarter of 1 percent went to Palestinians. Israeli settlements and infrastructure were granted the remaining 99.76 percent.

The Oslo agreements were designed to be temporary, to regulate affairs for a “transitional period” of five years, by the end of which Israelis and Palestinians were to agree on more permanent arrangements. Presenting the Oslo II Accord to the Knesset, Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin said that the permanent arrangement he envisioned would give the Palestinians “an entity which is less than a state.” The Palestinians hoped to get more. One month later, Rabin was assassinated by a right-wing Israeli implacably opposed to the accords.

In 1997, the year mandated by Oslo for negotiations over a permanent arrangement to begin, the World Zionist Organization settlement division published the fourth major settlement plan. Known as the “Super Zones” plan, it took Sharon’s three Palestinian cantons and turned them into four, surrounded by “buffer zones” and “super zones” of Jewish settlement. The zones covered half of the West Bank. The plan aimed to add nearly 115,000 people in forty-six new sites for West Bank settlement—goals that the Israeli government long ago surpassed. Today, there are more than 250 settlements in the unannexed parts of the West Bank—including cities, suburbs, industrial zones, rural communities, and “outposts,” which are settlements built without formal approval though in fact supported by the state with funding, construction, infrastructure, and defense—and more than a dozen settlement neighborhoods in the annexed areas of Jerusalem. Together, they have a population of more than 683,000 Israelis, one in every ten Jewish citizens.

All plans for the West Bank have accommodated these settled facts on the ground. Oslo—the only Israeli-Palestinian peace accord that has been implemented—set a precedent by drawing a line that included every settlement within the area under full Israeli control. When Prime Minister Ariel Sharon later constructed the separation barrier, it was routed to include many of the major settlements, conforming very closely to the lines of his 1977 map. Sharon had originally planned a second separation barrier in the east, putting walls on both sides of the West Bank’s major population centers and taking over the rest for Jewish settlement, just as in his 1977 plan. And every peace proposal introduced by the US or Israel, from President Clinton’s 2000 parameters to President Trump’s 2020 Vision for Peace, has called for Israel to annex lands that contain either all or most of the settlers.

Israeli leaders have offered different names for the Palestinian entity in the remaining, unannexed territories. Rabin called it “less than a state.” Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu called it “a state-minus,” or “autonomy-plus.” Former Defense Minister Moshe Yaalon said, “From my standpoint, they can call it the Palestinian empire.” And Ariel Sharon, who did use the words “Palestinian state” and led the first Israeli government to officially endorse one, also described, in a conversation recalled by former Italian Prime Minister Massimo D’Alema, the outcome he envisioned with a different word: “Bantustans.”

VIII

At the hospital in Ramallah, Abed heard from another parent that Milad was among three children who had been transferred from there to a different Hadassah hospital in Jerusalem, at Ein Kerem, formerly the Palestinian village of Ayn Karim. Barred from going himself, he called a cousin in Dahiyat al-Salaam who had a blue ID. Over an hour later, the cousin reported back: there were indeed three victims of the accident there, but none was Milad. Then news came that the second school bus was returning to Anata. Abed called one of his brothers, asking him to go greet it. A few minutes later, his brother called: “Milad is not here.”

Further whisperings made their way to Abed throughout the day: your son is at the military base opposite al-Ram; your son is in an Israeli hospital; Israel has permitted Nour al-Houda parents with green IDs to cross the checkpoints to Jerusalem. Abed continued to stand at the door to the emergency room, refusing to answer questions from reporters. By late afternoon, most of the parents concerned had located their children among the roughly seventy-five kindergartners who had been riding on the two buses. Only Abed and a handful of others had not.

Unbeknownst to Abed, in the room next to where he waited lay six corpses. One belonged to a thirty-nine-year-old teacher, Ula Julani, who had escaped from the bus, extricated several kindergarteners, and died after returning to rescue more; the school would later be renamed after her. The other five were children. Three of them were too burned to be recognized. Two others, a girl and a boy, were not.

Although he wanted to go search for his son in Anata, Abed had a feeling that Milad was near him. Something inside told him that he shouldn’t leave. As the parents and children around him departed, he learned from the hospital staff that there were bodies in the adjacent room. He desperately wanted to go inside. His nephew, who worked in Ramallah and had joined him at the hospital, urged him not to. A doctor came out, saying that he wanted to select parents to identify the bodies that were recognizable. The doctor asked Abed the color of his son’s hair. “Blond,” Abed replied. “You need to stay here,” the doctor said. “The hair of the boy who can be recognized is black.”

At that moment, Abed confronted the very real possibility—what now seemed, in fact, like a near-certainty—that Milad’s badly charred corpse was on a table in the next room. He and his son Adam gave the medical staff DNA samples. Even so, Abed held out hope that Milad might be alive—there were still more parents missing children than there were corpses in that room; one family did not find their son at the Hadassah hospital until the following day. Perhaps Milad was at the Israeli military base, after all. Perhaps he was at a different hospital. Perhaps one of the bystanders who had transported victims in private cars had taken Milad to a home in al-Ram or Jerusalem, where a family was now feeding him and trying to locate his parents.

IX

In April 2014, National Vision—The Center for Zionist Leadership, a program for the political education and training of Israeli youth, hosted a lecture in Haifa by Dani Dayan, who was then the chief foreign envoy of the Yesha Council, the umbrella organization of settlement municipal councils. Dayan had recently stepped down as chairman of the organization, which he had led from mid-2007 to 2013. Among his hires at Yesha was Naftali Bennett, now a prominent right-wing politician and a former minister of, among other portfolios, economy, education, and defense. During Dayan’s tenure at the Yesha Council, the West Bank settler population increased by more than one third. This despite the fact that it was the period of President Barack Obama’s first term, which Israeli officials had characterized as extraordinarily tough on settlements. “I am convinced that at some point in my tenure as chairman,” boasted Dayan, who was invited to meetings at the Obama White House, “the settlement [enterprise] in Judea and Samaria became irreversible.”

Dayan was born in Argentina to a Jewish family that had come from Ukraine. On his parents’ wall there hung a portrait of Vladimir “Ze’ev” Jabotinsky, leader of the Revisionist movement that evolved into today’s Likud. In 1971, when Dayan was fifteen, his family immigrated to Israel. A decade later, his father became Israel’s ambassador to Guatemala. Dayan spent seven years in the Israeli army, and then founded and became chairman of Elad Software Systems, a technology firm with roughly one thousand employees. In 2016, he followed his father’s footsteps into the Foreign Ministry, becoming Israel’s Consul General in New York. Ahead of the March 2021 election, Dayan joined New Hope, a party recently founded by former Likud minister Gideon Sa’ar.

That day in 2014, Dayan was introduced by National Vision’s founder, Ariel Kallner, who was then thirty-three years old. Today, he is a Likud legislator in the Knesset, where he is a member of the Caucus for Sovereignty (a parliamentary group that presses for annexing the West Bank), chair of the Caucus for Strengthening the Status of the Temple Mount (increasing Jewish prayer and presence at the al-Aqsa Mosque compound in annexed East Jerusalem), and chair of the Caucus for the Fight Against Delegitimization and Anti-Semitism (combatting criticism and boycotts of Israel and its settlements). Kallner told the audience that before Dayan’s lecture on hasbara, the Hebrew word for “explanation,” which also has the sense of “propaganda,” his organization thought it important to provide havana, understanding, about the conflict. To that end, Dayan’s talk would be preceded by another one, delivered by David Bukay, a professor of political science at the University of Haifa. Dr. Bukay’s lecture was later posted to National Vision’s YouTube channel under the title “The Palestinians: The Parasites of the World.”

Articles in the Israeli and international press often describe Dayan as charming. He has a friendly demeanor, portly frame, and cherubic face. His presentation that evening, “The Palestinians Talk About Justice, We Talk About Interests,” began with an analogy. The settlement enterprise, he said, was a table that stood on four legs. The first of these—“bringing a critical mass of people to Judea and Samaria”—was in place. If, in 1993, “there hadn’t been over 100,000 residents in Judea and Samaria,” he said, not counting settlers in annexed East Jerusalem, “the Oslo Accords would have included Israel’s total withdrawal. Just the fact that there were many residents, albeit many fewer than there are today, prevented an even worse agreement.” In fundraising, too, the settlements had done well: “We have a lot of moochers, in the good sense of the word, who go abroad and bring money for an ambulance, a synagogue, a school.” Missing, however, were the other three legs: political support within Israel’s main parties; backing by the Israeli public; and global advocacy “among opinion leaders—first and foremost in the US and Europe, the two elements that have the greatest influence and as a result have an effect on Israeli public opinion.” It was the absence of these three legs, he asserted, that had allowed Yesha to suffer its only significant setback in decades of settlement: Israel’s decision to “expel” its citizens and withdraw from Gaza at the height of the Second Intifada.

Dayan was speaking in the final weeks of the Israeli-Palestinian negotiations led by Secretary of State John Kerry. A little over a year earlier, Kerry had told the House Foreign Affairs Committee, “I believe the window for a two-state solution is shutting. I think we have some period of time—a year, a year-and-a-half to two years—or it’s over.” Dayan mocked Kerry’s intelligence—“I was going to add an adjective to describe how smart he is, but I won’t”—and said his diplomacy was certain to fail. But with Kerry’s prediction of the imminent demise of Palestinian statehood he agreed: “We are currently, to some extent, at a historical point in the conflict, for the first time since the Peel Commission in [19]36–[19]37 that recommended partition,” he said. “The global community will realize that this issue”—a division of the land under Israel’s control—“should be taken off the table. It’s not going to happen. Not because the world doesn’t want this to be the solution, but because it understands that this isn’t the solution; it isn’t doable.”

Dayan stressed that there were still many obstacles ahead, some of them self-created. “One of the things that most hinders settlement in Judea and Samaria is the Israeli standpoint that supports two states. It’s very hard—I admit—very hard to explain Israel’s policy that on the one hand says two states and on the other builds in Judea and Samaria.” For Dayan, this does not mean, however, that Israel should now promote alternatives, such as giving citizenship to the Palestinians, as some settlers, as well as leaders like Israel’s president, Reuven Rivlin, have proposed. “I think the ideas that are being voiced, also among us, about one state, granting citizenship, these are very dangerous ideas. We must head in entirely different directions. But to that end we must have enough time to increase the number of Jews who live in Judea and Samaria.”

In many ways, Dayan was echoing the Zionist leaders of the pre-state era. They, too, had argued that international efforts to settle the conflict must be parried and delayed until Jews had achieved their goal of taking over the land and becoming a majority. Yet the task before the Yishuv, as the Jewish community in Palestine was called before the foundation of the state of Israel, was immeasurably more difficult than that of settling the West Bank today. In 1882, Vladimir “Ze’ev” Dubnow, a member of Bilu, the first group of Zionist settlers, sent a letter from Palestine to his brother, the renowned Russian historian Simon Dubnow. He wrote that the ultimate aim of the Jewish pioneers was “to take possession in due course of Palestine and to restore to the Jews the political independence of which they now have been deprived for two thousand years. Don’t laugh, it is not a mirage.” Jews were then 3 percent of Palestine’s population. “The means to achieve this purpose could be the establishment of colonies of farmers in Palestine, the establishment of various kinds of workshops and industry and their gradual expansion—in a word, to seek to put all the land, all the industry, in the hands of the Jews…. Then the Jews—if necessary, with arms in their hands—will publicly proclaim themselves masters of their own, ancient fatherland.”

Theodor Herzl, whom Israel’s declaration of independence calls “the spiritual father of the Jewish state,” was critical of what he referred to as these early “attempts at colonization,” arguing that it was mistaken to establish settlements before Jews had been granted a state. In his influential 1896 pamphlet The Jewish State, Herzl wrote:

Important experiments in colonization have been made, though on the mistaken principle of a gradual infiltration of Jews. An infiltration is bound to end badly. It continues till the inevitable moment when the native population feels itself threatened, and forces the Government to stop a further influx of Jews. Immigration is consequently futile unless we have the sovereign right to continue such immigration.

Herzl thus called for the Zionist movement to first win the support of the great powers for a Jewish state, preferably in Palestine: “We should there form a portion of a rampart of Europe against Asia, an outpost of civilization as opposed to barbarism. We should as a neutral State remain in contact with all Europe, which would have to guarantee our existence.” The Ottomans, however, rebuffed Herzl’s overtures, and in 1905 the majority of Zionists—who were then mostly from Eastern Europe and, contrary to widespread perceptions, religious—rejected the offer he had secured from the British to settle in East Africa, preferring to try their luck in the Land of Israel instead.

From that moment until today, the Zionist movement has sought to explain the justness of its cause, which was the focus of Dayan’s lecture on hasbara. Why did a small number of Jews, coming mostly from the Russian empire, have the right to take over Palestine against the will of the native majority? In 1918, the Jewish Yishuv, which by then had grown to nearly 8 percent of Palestine’s population, argued against applying the normal principles of democracy and self-determination to Palestine. Ahead of the Paris Peace Conference, which decided the Treaty of Versailles after World War I, Yishuv leaders drafted a plan for a provisional government that “in all matters” would ensure “a decisive voice belongs to the Jewish people throughout the world.” The Russian-born Jabotinsky, a co-drafter of the plan, explained the need to thwart the establishment of representative democracy: “If there is a normal constitution here, responsible for the ‘majority,’ then the majority of us would never enter.” At a Zionist Congress debate thirteen years later, the Revisionist leader defended his illiberal demand that no democracy be established until Jews had a majority, arguing to his fellow Zionists that Herzl’s proposals had been even less democratic. In Herzl’s vision, Jabotinsky argued, “the country would be ruled by a Jewish administration before the Jews became the majority, as an instrument, a kind of mandatory power, for settlement.”

Even when presented for the first time with a proposal for partition that would establish a Jewish majority, which is what the Peel Commission plan of 1937 did under the British Mandate, the Yishuv’s leader, David Ben-Gurion, said that he would accept it only as a step toward obtaining the whole of Palestine. The Peel plan followed the same principle as its two-state successors: Jewish territory was assigned by drawing a line to encompass nearly all existing Jewish settlement. This left a small number of Jews in the area allotted for the Arab state, about 1,250 of them, and a large number of Arabs in the area of the Jewish state, 225,000. The plan called for both these populations to be transferred, noting that “room exists or could soon be provided within the proposed boundaries of the Jewish State for the Jews now living in the Arab Area. It is the far greater number of Arabs who constitute the major problem,” as there was no surplus of cultivatable land for them in Palestine.

The most appealing aspect of the plan for the Polish-born Ben-Gurion was the idea of population transfers, which provided the Jews “an undreamed of possibility, one which we could not dare to imagine in our boldest fantasies.” Ben-Gurion was not alone. Both before and after the British had proposed it, many other Zionist leaders had also favored transfers, beginning with Herzl, who had written in his diary in 1895: “We shall try to spirit the penniless populations across the border by procuring employment for them in the transit countries, while denying them employment in our own country.”

For Ben-Gurion and the Zionist leadership, the great flaw of the Peel plan was that it didn’t give Jews all of the land. During the dramatic Yishuv debate over partition, Ben-Gurion argued for accepting the proposal as an interim step toward obtaining Eretz Israel, the Land of Israel. “A Jewish state on only part of the land is not the end but the beginning,” he wrote in a letter to his son, “[…] a powerful boost to our historical endeavors to liberate the entire country.” The Jewish state would have “an advanced defense force—a superior army which I have no doubt will be one of the best armies in the world,” he continued. “At that point I am confident that we would not fail in settling in the remaining parts of the country, through agreement and understanding with our Arab neighbors, or through some other means.”

His words proved prescient. It was only after the establishment of a state that the Zionist movement could undertake what Ben-Gurion, speaking then as prime minister, in 1951, called a “project of colonization far greater than all of the last seventy years.” When the UN had proposed its partition plan in 1947, giving to the 31 percent Jewish minority the majority of the land, the Yishuv then possessed less than 7 percent of the territory. Most of this land had been bought, largely from absentee landowners. After the ensuing 1947–1949 war had ended, Zionist organizations and the new state of Israel were able to take over most of the land in Mandatory Palestine, not through purchase but confiscation. By 1953, 350 of 370 new Jewish settlements had been established on Palestinian-owned land. Palestinian refugees of the war were not permitted to return. Thousands of Palestinian refugees were shot and killed as they tried to sneak back to their homes and reunite with their families under the cover of darkness. The land and property of Arab refugees was seized. So, too, was much of the land of the Palestinians still under Israel’s control, many of them internally displaced by the war and prevented from returning to their villages.

Israel gave citizenship to the Palestinians within the Green Line, and trumpeted its democratic values to the world. But it placed them under a repressive military regime that imposed curfews, permit requirements, travel restrictions, bans on political parties, detention without trial, and closed security zones where Jews but not Palestinians could travel freely. In addition, Palestinian villages were blocked from accessing roads used by neighboring Jewish communities. The 1948–1966 military government meted out cruel punishments, such as forcing Palestinian citizens to walk several miles to report to a police station three times per day or to stand under a tree from sunrise to sunset for a period of six months. Children as young as eight were interrogated about their political views. Youth were clubbed during random ID checks. Punishments were given to those who failed to greet the military governor. Israel’s military rule could not be justified on security grounds: the Palestinian citizens of Israel were quiescent. Shortly before Prime Minister Ben-Gurion left office in 1963, Minister of Labor Yigal Allon told him that dismantling the military government would be “one of the smallest risks we have undertaken in the eighty years of Jewish settlement in the Land of Israel.” The main purpose of military rule, as in the West Bank today, was to facilitate land expropriation.

Nearly a third of the territory under Israel’s control was placed under military government, a significantly greater portion than the 22 percent now under occupation. By 1964, Palestinian citizens of Israel had lost more than three-fourths of their land. At that point, the military government was no longer needed. It was shuttered in December 1966. As senior government officials decided which closed military zones would be opened and in what order, they stated that areas that had been closed to Palestinians for “land reasons”—preventing internally displaced citizens from reaching their homes—would be opened only “after stated conditions are fulfilled.” These included “demolition of structures in abandoned villages, forestation, declaration of nature reserves, fencing and guarding.” The military government ended but many of its methods of control were simply transferred to civilian bodies whose powers were expanded. The Arab affairs adviser to the prime minister said the change was mainly “psychological.”