My friend Suketu likes to talk about his Gujarati parents’ surprise when they moved here in the seventies from India. They marveled then at how people who back in Bombay had been at each other’s throats—Hindus and Muslims, children of Bangladesh and Bangalore—now shared buildings and streets in a land whose rule of law and promise of a better life allowed them to bury ancestral grudges (at least when not behind their apartments’ closed doors). Suketu and his Indian friends called their Queens neighborhood Jaikisan Heights. Their Colombian neighbors called it Chapinero, along a stretch of 37th Avenue that’s lined with the same purveyors of cheesy buñuelos and passionfruit cholados you’ll find in a desirable district of the same name in Bogotá. The Indians and Colombians and Bangladeshis are all still here. But now they’ve also been joined by Hondurans and Afghanis and Tibetans and speakers of Mexico’s indigenous languages from Oaxaca and Nayarit. Each group has its own nicknames for this part of north-central Queens that’s grown famous to demographers for its density and diversity of the kind of people—immigrants—who know better than anyone the power of names to register both possibility and limitation, obstacles and aspiration.

The few square miles around LaGuardia Airport that contains Jackson Heights and the adjoining neighborhoods of Corona and Elmhurst—and which became known, last spring, as the “epicenter of the epicenter” of a global pandemic—is home to speakers of more languages than any comparably sized piece of the world’s skin. In New York today, according to the Census, some two hundred tongues are spoken. The real number, according to my linguist friends at the Endangered Language Alliance, is at least eight hundred and perhaps many more—a number that makes New York City in the first decades of the twenty-first century not merely the most linguistically diverse city in world history, but the most linguistically diverse city that will ever exist. Over the past several millennia, linguists say, human beings have communicated with each other in tens of thousands of tongues, but are now down to some seven thousand—and losing more by the week. What dies with the last speakers of endangered languages from the Himalayas or the Americas’ first nations or Italy’s old regions, whose discrete dialects have been subsumed under “standard Italian,” aren’t just words—gone, too, are entire histories and mythologies and ways of describing life on earth. But it’s a remarkable fact of New York’s current ethnic mix that many of those endangered languages are kept alive by those driving cabs or busing tables in the city now. Words birthed to describe Bhutan’s peaks or the forests of Guatemala are being used today to describe the concrete jungles of New York. And nowhere is the density of such tongues more palpable—or audible on the streets—than in the neighborhood where Suketu and I like to meet up for Salvadoran pupusas, or parathas from his homeland, with Ross or Daniel from the Endangered Language Alliance and members of their marvelous network—speakers of Quechua and Garifuna and the ǂ’Amkoe tongue, from Botswana, that sounds like kissing. If we’re lucky, Suketu will treat us all to a few words from one of the tongues that all this mixing has birthed in New York: the Gujarati-Yiddish pidgin that his family of diamond merchants, engaged in a business long dominated here by Jewish Hasidim, employed to haggle over jewels.

The story of what transformed this once-white enclave into a world-historical Babel of people and languages, and a marvelous microcosm of polyglot New York now, is a story in part about two key pieces of legislation from the era of Civil Rights that transformed the United States. One is the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, which ended old limits on immigration from the world’s “darker nations,” and the other is the Fair Housing Act of 1968, which made discrimination in housing against minorities, including those new arrivals, illegal. The combined result was a tide of new people from a number of world regions entering the housing market—South Asia, the Caribbean, West Africa, South America, and the Middle East—who were previously underrepresented in New York’s ethnic mix. With them came new patterns of residence that transformed the names that fill its neighborhoods.

Since 2004 in lower Manhattan, a piece of Allen Street running between Chinatown and where the Lower East Side once served as a famous landing place for new arrivals from Europe’s impoverished fringe has borne the official co-name Avenue of the Immigrants. Today that part of the Lower East Side is a landing place less for immigrants than for NYU grads with trust funds and faux-bohemian bankers. The Avenue of the Immigrants would perhaps be a more appropriate tag for any number of thoroughfares—Roosevelt Avenue in Queens, 149th Street in the Bronx, Neptune Avenue in post-Soviet southern Brooklyn—that now serve as vital hubs for new arrivals to a city whose foreign-born residents and their kids now compose a third of the city’s populace, the same proportion as at Ellis Island’s peak. The “new immigration” shares much with the old. But among its distinctions are the ways that today’s “transnational” immigrants have been able—with the help of the Internet, cheap airfare, and money-wiring services whose outlets occupy what seem like every other storefront on such immigrant thoroughfares—to maintain strong ties to home nations for which remittances are a lifeblood. Another is the lack of pressure they feel, unlike the European immigrants who once flocked to New York’s docks, to dive headlong into a melting pot whose end effect and goal, for the Germans and Irish and others who embraced its heat in the nineteenth century, was to shed their foreign identities and accents to become American by becoming, in a word, generically white.

Advertisement

Such groups’ success in doing so is registered by the many street and neighborhood names that once marked their enclaves but are now long gone. The successful assimilation of New York’s once highly visible populace of ethnic Germans into the undifferentiated mass of American whiteness was marked not merely by the transformation of, say, Drumpfs into Trumps, but also by the disappearance from New York’s map of Rhinelanders’ Row, Rhinelanders’ Alley, and Rhinelanders’ Wharf. For other historic groups whose climb to whiteness took longer, such name changes were even more common. There’s a reason that I have cousins, on my family’s Schapiro side, who became Shephards to get ahead in business: It’s the same reason there are countless Jews here named Green and Edwards whose forebears were Greenbergs and Epsteins, who perhaps lived, when there were such places in lower Manhattan, on Jew Street or Jews Alley.

Manhattan’s Chinatown is home not merely to restaurants owned by the old immigrants’ heirs who’ve moved to the ’burbs, as in nearby Little Italy, but also to the kinds of businesses—banks, hair salons, funeral parlors—that indicate its status as a living destination for new arrivals from Guangdong and Fuzhou. Since the first Cantonese laundries and boardinghouses opened on Mott and Bayard Streets in the 1870s, the old Dutch and English names of nearby blocks have grown steeped in Chinese lore: the curving block of Doyers Street, once home to America’s first Chinese-language theater, became known as Bloody Angle, thanks to its popularity as a place for local tongs’ “hatchet men” to ambush rivals. From that day to this, the area’s residents have never seemed too concerned with changing its public nomenclature or trumpeting to outsiders the fact that, say, the lingua franca of the neighborhood’s East Broadway corridor now isn’t Cantonese but Fujian. The same is true of Mandarin speakers from China’s north and west who’ve also traversed the Golden Door to establish swelling new Chinatowns in Flushing, Queens, and along the N train’s route across southwest Brooklyn from Sunset Park into the bit of Bay Ridge that was once Norwegian-tinged but is now dominated by daughters and sons of Fuzhou. Part of the reason they call their enclave there “Eighth Avenue” has to do with the numbered name of its main shopping drag. Another is to do with the number eight’s association, in their culture, with luck.

There are doubtless hundreds of such place-words here that were coined by language speakers much less numerous than China’s to riff on their own tongues’ words for luck or peril or hope, or to describe new homes for themselves or far-off kin. Most such instances of place-making-through-naming never become official, or are even unknown to non-speakers. Many others become vital neighborhood landmarks, not marked by any sign but known to all: Every habitué of South Harlem will tell you that 116th Street between Lenox (aka Malcolm X) and Frederick Douglass is Little Senegal. There are new arrivals to the city, notably those not carrying papers or who’ve come as refugees, for whom proclaiming their presence is a danger. But where some older enclaves had names born more of others’ prejudice than their own pride, there’s a marked trend now to turn their presence into a name on a street (or several).

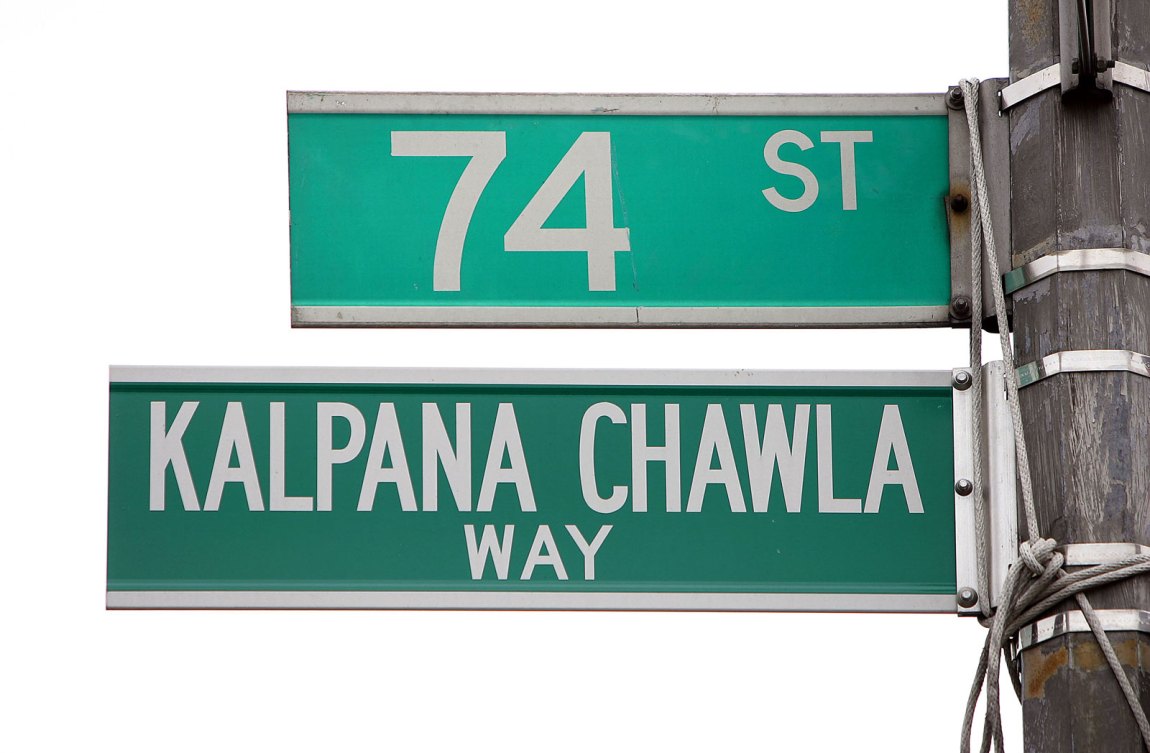

Where Manhattan has its official Little Brazil, Queens now boasts a Tibet Place and Calle Colombia. If a driven group of petitioners get their way in Woodside, it may soon have a Little Manila, too. The Bronx has a sign, over a stretch of Starling Avenue dominated by Bangladeshis, stating its name as Bangla Bazaar. In 2017, both that borough and Brooklyn gained streets that signal both boroughs’ boom in populace from Mexico: They’re called Cinco de Mayo Way, in honor not of the holiday on which patrons of Mexican restaurants love to drink, but of a famous nineteenth-century battle in the Mexican city—Puebla—from whence many of New York’s Mexican immigrants hail. City Councilman Danny Dromm is a pink-skinned holdover from the area’s past who loves its present (“Why shouldn’t a gay Irishman represent America’s most diverse neighborhood?”); he has sponsored other honorary names there, including Mount Everest Way, which hails its Nepalis, and Diversity Plaza, down by the subway stop where Desi–dominated 73rd Street meets the Ecuadoran-owned check-cashing joints of Roosevelt Avenue. Many members of the city’s new ethnic communities, it seems plain, have come to feel like Haitian American state assemblywoman Rodneyse Bichotte, who saw her years-long quest to have part of Flatbush renamed Little Haiti come to fruition after Donald Trump called her homeland a “shithole”: “We thought it was time,” Bichotte said, “to reclaim our territory” and “let people see who we are.” (The only parallel municipal honor is gaining an annual parade.) Others have availed themselves, in the hunt for recognition, of more digital modes of place-making. In the Morris Park area of the Bronx that boasts a street named for native son Regis Philbin, a Yemeni control supervisor at JFK airport named Yahay Obeid successfully petitioned Google Maps to splash a large label over the blocks where Mr. Philbin played as a boy and where the children of Obeid and a critical mass of other Yemenis do now. It reads, in Google’s all-caps font, “LITTLE YEMEN.”

Advertisement

Such quests for recognition, by immigrants and others on the city’s margins who’ve used the power of names to make its streets home, are allied to other trends in a city whose dominant culture and norms keep shifting. Once upon a time, New York’s abundant Jews hid their heritage. Now the city’s mayor is dogged by accusations of having changed his original German name (he was born Warren Wilhelm, Jr. before becoming Bill de Blasio) to appeal to Jewish voters. And many immigrants are rejecting altogether the need felt by their forebears to fit in. The novelist Viet Thanh Nguyen, in one of the New York Times’ most read op-eds from recent years, titled “America, Say My Name,” describes his experience as an immigrant kid trying to do so by calling himself “Joey” and “Troy”—and his determination, now, that his fellow Americans call him by his true name. Nguyen’s essay also included riffs on a student whose name was Yaseen but who wished it wasn’t, and on Nguyen’s own decision to name his own son Ellison, after the author of Invisible Man. He concluded it thus: “Yaseen. Ellison. Viet. Nguyen. All American names, if we want them to be. All of them a reminder that we change these United States of America one name at a time.”

That we do. And the reminder only seems to gain urgency as people here and everywhere, during the presidency of a New Yorker openly hostile to their aims, grow increasingly keen to confront names and monuments that honor figures or values that don’t match evolved modern mores. And many are determined not merely to see such markers removed from the public square, but also to erect new ones that make underknown histories and figures newly visible in public life.

A NAME, it may be true, can never be completely divorced from its root. But a name is also an opportunity. And it’s a hope—at the least, a hope by its coiner that it will stick: that its destiny will be more akin to, say, the fate of Adam Clayton Powell’s namesake avenue in Harlem than that of the official moniker, since 2008, of the Robert F. Kennedy Bridge, which no New Yorker doesn’t still call the Triborough. (How do you distinguish if the person describing their drive into Manhattan from Queens or the Bronx is a native or a tourist? Listen for reference to “the Robert F. Kennedy Bridge.”) The reason some new names stick and some don’t can have less to do with politics than with euphony—than with the way a name strikes our ears or rolls off our tongues or suits a story’s beats. But, fundamentally, the reason a name sticks is the image or vision it offers of a place and its people.

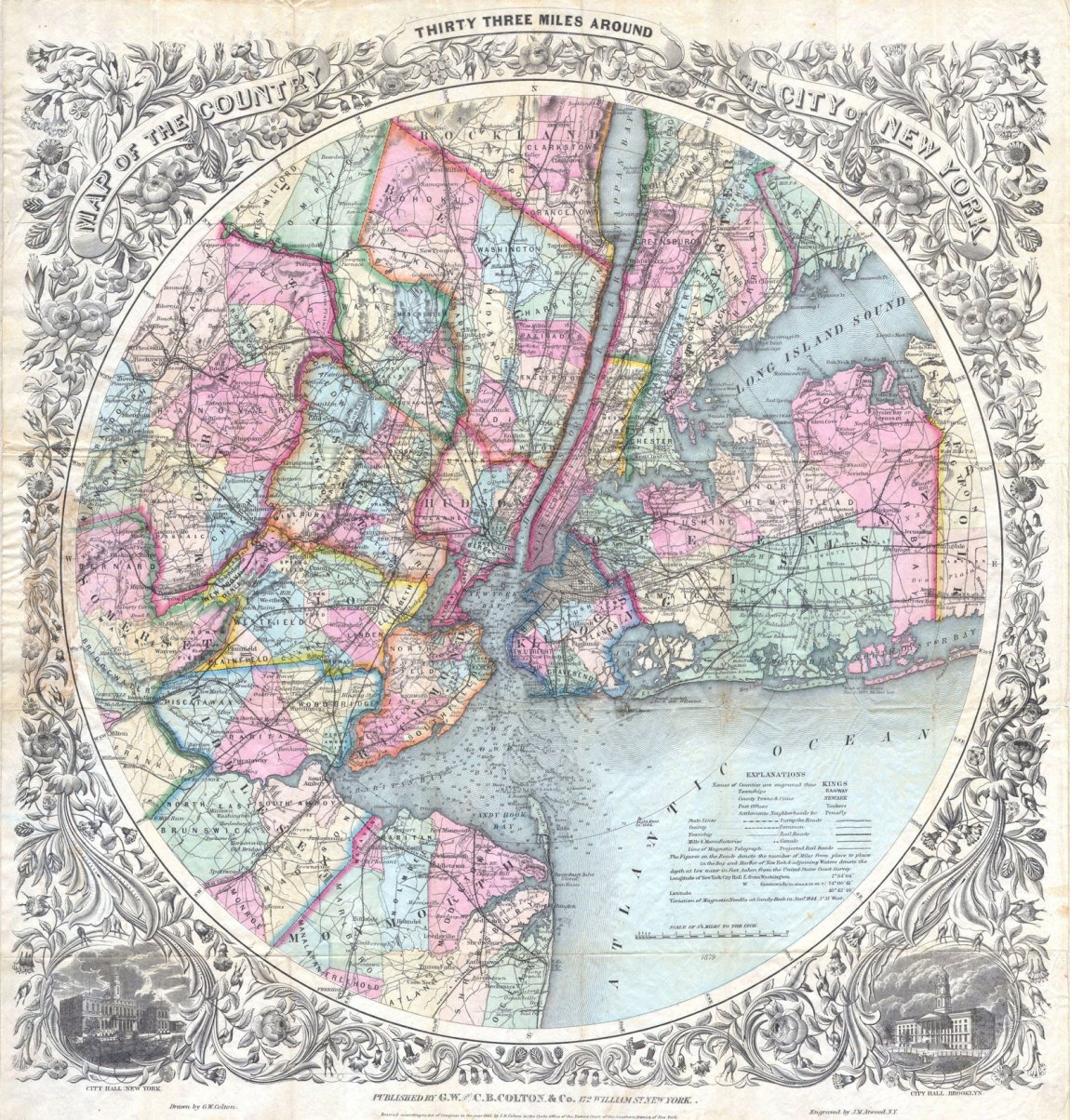

“Landscape is history made visible,” wrote the geographer J. B. Jackson. In recent years, I’ve led workshops on maps and mapping in each of New York’s boroughs and have seen this truth up close. Asking participants in those workshops to visually represent landscapes both traversed and imagined produces an astonishing range: maps of quiet and of noise; maps of memories and of happiness; maps with made-up names (“Ex-landia”: don’t go where my ex lives); maps of places where refugees seek sanctuary; maps of the streets where one feels most comfortable on two wheels (as playfully and poignantly represented by a young woman I met who runs an organization called The Brown Bike Girl); maps of the curb cuts and elevators that make urban life possible for those of who are disabled and get around not on two wheels but on four. Each of us, in these ways, inhabits a different city. Each of us, in the names we use to navigate it, also lives in one that is shared.

If landscape is history made visible, the names we call its places are the words we use to forge maps of meaning in the city. On its streets, we make our way to different fates, but also intersect, if sometimes for only a moment, in shared spaces whose names can embody common understanding—and can become the signs under which we learn not merely to see each other but to see through, too, to possible futures.