“The culture shock of defeat is my archetypal image,” the photographer Shomei Tomatsu (1930–2012) once said. “No matter where I go, I carry the shadow of war.” And Daido Moriyama (born in 1938), whom Tomatsu mentored, declared: “I wanted to go to the end of photography.” The two artists, relatively close in age, began their careers at a time of radical change in postwar Japan, and they enjoyed a deep, lifelong friendship based in their work.

Japan, devastated by its defeat in World War II and deeply wounded by the traumas of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, then sought a new identity while both resisting and accommodating the growing influence of American culture. Tomatsu and Moriyama both lived, on and off, in Tokyo, sharing a fascination with the street life of Shinjuku and Shibuya, two of the city’s nonconformist, marginal neighborhoods. Both were born into what has been called “the generation of distrust,” and they were instrumental in Japanese photography’s breaking with the formalism that defined its earlier practice; they pioneered instead a new kind of “subjective photography practice” rich in emotions, as the curator Simon Baker writes in his text for the exhibition catalog.

Late in their careers, the pair had planned a joint exhibition as their first collaboration and as a way to celebrate their city, Tokyo. Nearly a decade after Tomatsu’s death, the exhibition installed at the Maison Européenne de la Photographie (MEP) finally fulfills their dream in an incarnation conceived by Baker, Daido Moriyama, and Yasuko Tomatsu (the artist’s widow), in consultation with the gallerist and publisher Akio Nagasawa and with a catalog that brings together essential texts by the artists. Not only does the exhibit bring to life and expand the two photographers’ original project, but it is also the first major Parisian exhibition of Shomei Tomatsu, and the occasion to see more than four hundred works by both photographers, many of them never exhibited before here.

In the years since MoMA’s 1974 “New Japanese Photography” and the more recent International Center of Photography’s “Heavy Light” exhibition, the history of photography has often reverted to its previous slant of being written from American- and European-centric points of view. Taking a new look at postwar Japanese photographers helps us envision an alternative history of modernism and the avant-gardes in which Tomatsu and Moriyama appear as leading figures of renewed relevance today. They were united in their keen attention to the production of refined photobooks and their common interest in series and sequences rather than the unique image, as well as in their commitment to photography as an experimental medium.

In his choice of subjects, Tomatsu’s early pictures—taken shortly after his arrival in Tokyo from Nagoya in 1954—reflect his political stance and his empathy: child beggars, crowds of grim-faced unemployed people, an exhausted homeless man sleeping on a public bench, struggling street vendors. All seem adrift, a vulnerable population trying to survive in a world where not only the fabric of urban life but many traditional beliefs and customs have frayed and come apart.

“Love and hate,” Tomatsu wrote, “are no more distanced than either side of a sheet of paper…. We were starving, and they [American servicemen] threw us chocolate and chewing gum.” His ambivalent attitude toward the US presence finds clear expression in his series Chewing Gum and Chocolate, which he began in 1958 and continued for twenty years, shooting in locations from Hokkaido to Kyushu. In what became a characteristic style, Tomatsu preferred an oblique view to a head-on confrontation with his subjects, and he liked to use an expressionist style that featured odd camera angles, unconventional crops, and dramatic contrasts of light and shadow, traits that Moriyama would also adopt. He found his material in the ramshackle towns around the military bases, with their bars, pawnshops, drug and liquor stores, tawdry nightclubs—and the escorts beloved by American soldiers.

After enduring fifteen years during which all reference to the two atomic bombing sites had been censored by American and Japanese authorities alike, Tomatsu conceived what is perhaps his best-known body of work: Hiroshima–Nagasaki Document 1961, followed in 1966 by Nagasaki 11:02 August 9, 1945. In the course of this long-term project, he approached survivors such as Tsuyo Kataoka, who had once been known for her extraordinary beauty, and asked them to display faces that had been deeply scarred by burns from the blast. Out of respect to these survivors, known as hibakusha, and what they had endured, Tomatsu often showed their faces, like that of Senji Yamaguchi, partly obscured in deep shadow. “I…learned that ruins lie within people as well,” he told critic Leo Rubinfien, in his 2004 book Shomei Tomatsu: Skin of a Nation.

Advertisement

Tomatsu also photographed small relics of the atomic devastation from which a sense of cataclysm still radiates: a stopped watch, a partially melted beer bottle that looks like a beef carcass painted by Chaim Soutine, the shattered statue of an angel from the Urakami Cathedral. Although Tomatsu’s feelings are perfectly plain, the photographs are understated rather than demonstrative: poetic, exploratory, and allusive.

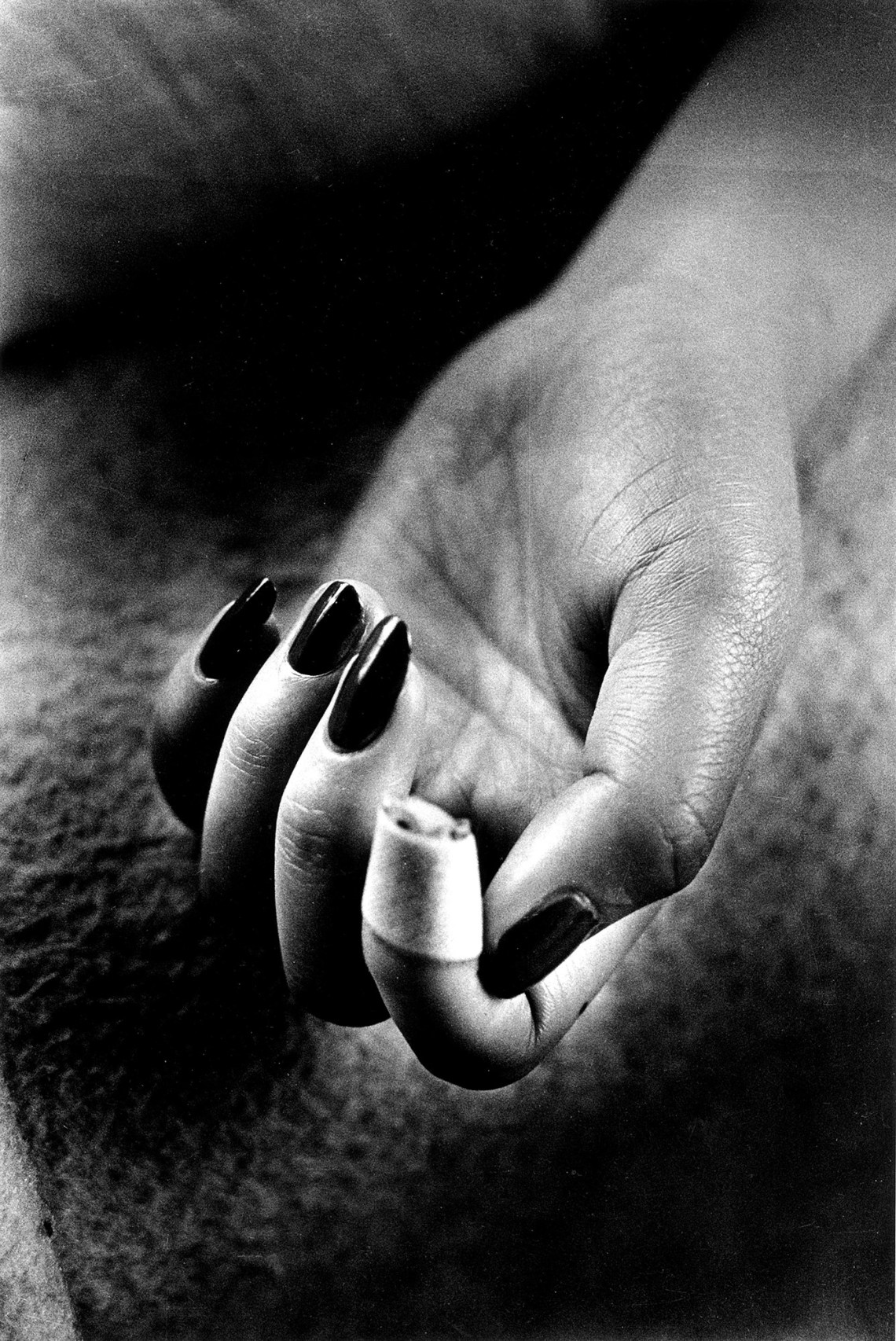

In the square prints of Asphalt (1961), Tomatsu shifted his perspective from a human one to what he called “gazing like a stray dog.” He concentrated on the detritus he found littering the sidewalk and gutter: a high-heeled shoe abandoned and marooned in mud, a discarded cigarette end. In the 1960s, for Ruinous Gardens, his first series in color, he staged mysterious, abstract Paul Klee-like still lifes featuring a small cosmos of shells, feathers, plant stems, crushed insects, and fish bones. As, later in life, Tomatsu became preoccupied with the natural world rather than the built environment, in the late 1980s he went back to this theme of remnants, photographing the tide of discarded fragments left on the beach in Chiba, on the eastern outskirts of Tokyo, where he lived, for his series Plastics. Although none of these three series directly depicts violence, the scattered fragments that feature in many of the images seem an echo, an aftershock, of the Nagasaki series.

In late 1960s and early 1970s Japan, a time when photography magazines such as Camera Mainichi, Asahi Camera, Asahi Journal, Sankei Camera, and Nippon Camera flourished, and photographers started to publish their work in books or in the avant-garde magazine Provoke, Tomatsu explored a new counterculture rich in grassroots movements protesting consumerism, overdevelopment and pollution, militarism, the colonization of Okinawa, the war in Vietnam, and the Japan–US Security Treaty. These demonstrations, and contemporary politics in general, were topics that Moriyama tackled only briefly but that were much more central to Tomatsu. In Tomatsu’s 1969 series, Protest, images of clashes between students and riot police resemble choreographed, ritual scenes: rain glitters on the ground, while movement makes figures fuzzy, protesters and police alike shrouded in clouds of billowing gray amid a fight whose outcome seems uncertain.

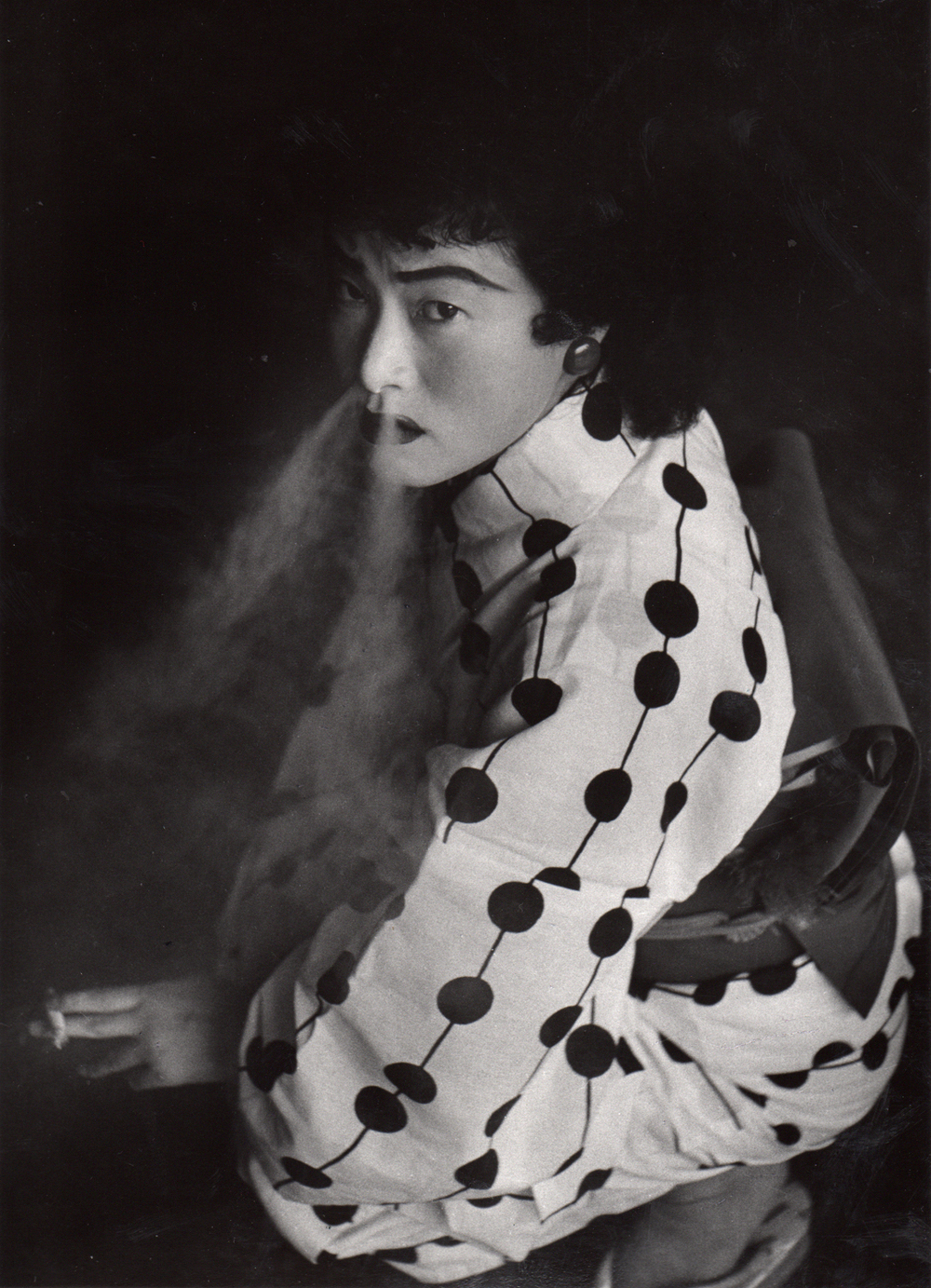

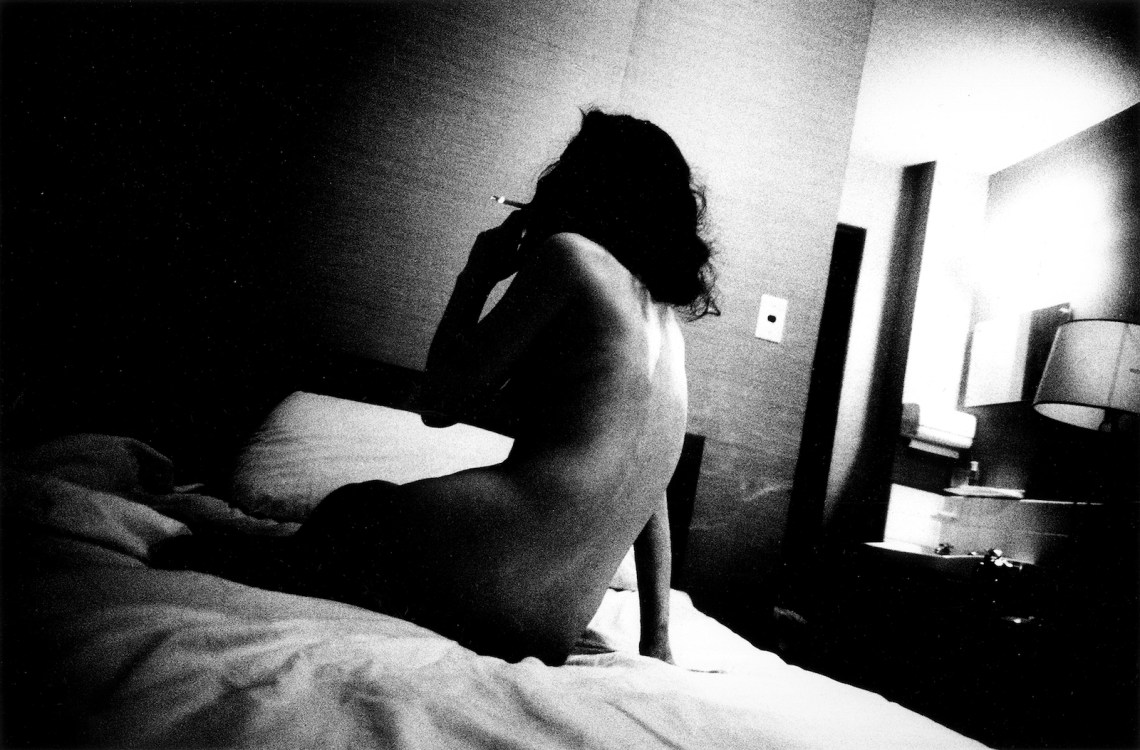

Tomatsu and Moriyama shared a lifelong interest in Tokyo’s more outré neighborhoods—notably, Tomatsu prowled bars and nightclubs for his late 1960s series Eros and Oh! Shinjuku. The latter had by then become a booming neighborhood, a center for the sex and drug trade where underground cinemas and experimental theaters coexisted with striptease clubs. One of his strongest images shows two Butoh dancers in extreme close-up, their faces pressed against each other: the man looks away while the woman, crushed into him, has an expression of frozen ecstasy, her enormous false eyelashes looking like black centipedes marching across her face.

In the 1970s and 1980s, Tomatsu continued with his exploration of color in the series Cherry Blossoms. But, proving himself capable of innovation and changes of direction (skills he shared with Moriyama), he produced looming, tightly cropped images that made the blossoms appear alien and slightly menacing. In Interface (1964–1975), Tomatsu shot ironic, pseudo-official staged portraits of himself and fellow photographers that send up formal Japanese portraits of the 1940s. He represents himself in the guise of two contradictory entities, caricatured symbols of Japanese life: a prisoner in shackles and a slouching yakuza gangster with a provocative gaze. Meanwhile, Nobuyoshi Araki, often criticized for his sexually subjugated representations of women, appears as a brash presence standing in front of political posters in bowler hat, three-piece suit, and his trademark glasses; Masahisa Fukase plays a naked survivalist carrying a fish net in a swampy landscape; and Moriyama himself appears costumed as a traditional bride in full makeup and cream-colored kimono, prefiguring the work of a younger generation of contemporary photographers such as Kenta Nakamura and Yasumasa Morimura.

When Daido Moriyama arrived in Tokyo as a young photographer from Osaka in 1961, his dream was to join the avant-garde photography collective Vivo, but he learned that they had just disbanded. He instead started work as an assistant to the photographer Eikoh Hosoe, who had been a crucial member of the group, but Moriyama admired another member, Tomatsu, above all, and sought him out as a mentor. “For me, as a photographer, without a doubt, everything began with Tomatsu,” he has said. But less critical than his mentor of the US presence in Japan, Moriyama welcomed American cultural influences—from Jack Kerouac’s On the Road and William Klein’s New York, through Weegee’s brash night shots, to Andy Warhol’s use of readymade images.

Advertisement

For this show, Moriyama, Yasuko Tomatsu, and Nagasawa gave each photographer a whole floor of the MEP, contrasting the light blue-green walls and classic sequences that demarcate Tomatsu’s show with Moriyama’s installation on deep blue or vivid pink walls, sometimes papered with photographic wallpaper, and chock-full of an accumulation of collaged prints. The rooms also feature vitrines, which contribute to an immersive environment that reflects Moriyama’s abrupt changes of style and his unrelenting exploration of different media, from gelatin silver prints to color photographs, wallpaper, photocopies, silkscreens on canvas, Polaroids, light boxes, magazines, and books. Especially books: propelled by a manic energy, Moriyama has so far published a staggering 150 titles in volume form.

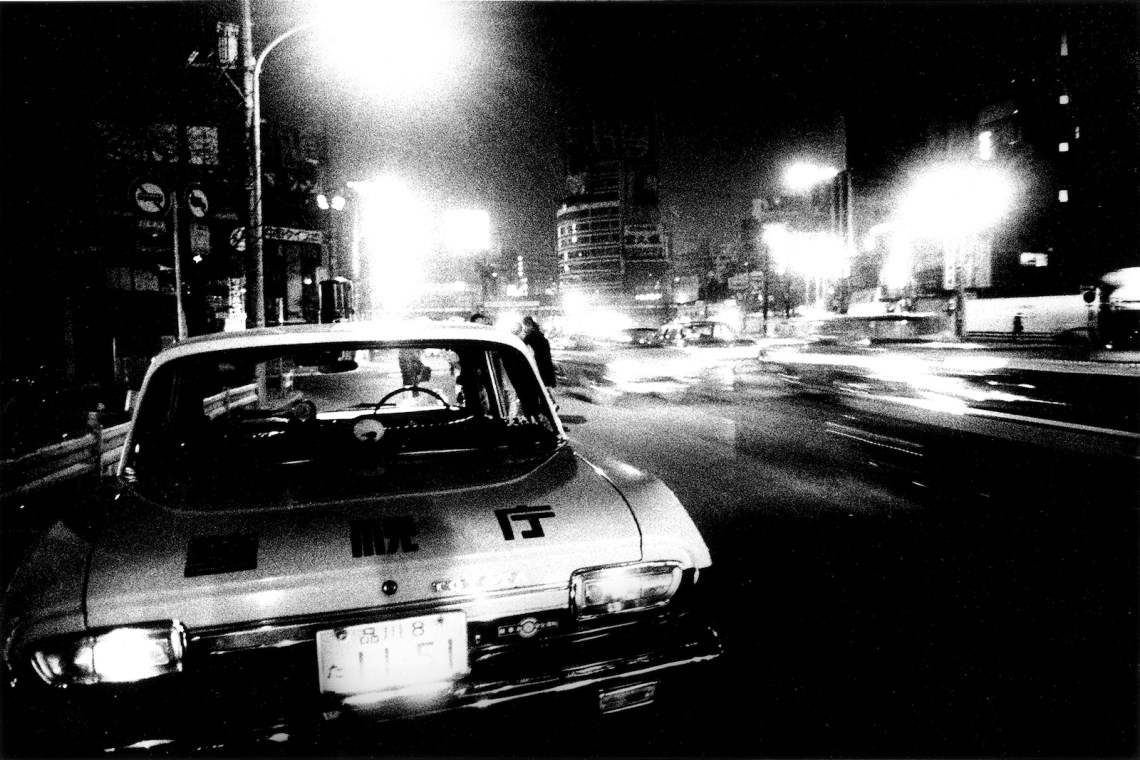

For his first, Japan Photo Theater (1968), Moriyama took photos while walking at a furious pace, often pointing his compact camera without looking through the viewfinder. The result is a hectic sequence of raw, unfiltered visual telegrams that reflect both his movement and that of the city; it is a technique that he, along with the photographers featured in Provoke magazine, calls Are-Bure-Boke (rough, blurred, out-of-focus). These abrupt, jumbled scenes—of dwarf show dancers, strip clubs, street performers, fetuses in formaldehyde containers, street scenes—that echo Tomatsu’s explorations in Chewing Gum and Chocolate (1958–1978), Eros (1969), and Oh! Shinjuku (1969), which jump from close-ups to slanted long perspectives, like a chaotic series of stills reminiscent of late 1950s and early 1960s noir films like Koreyoshi Kurahara’s 1957 I Am Waiting. To Moriyama, the city is a whirl of sounds, smells, and sights, a living organism that he absorbs and to which he reacts in a split-second.

Moriyama claims that no photograph is an original. “Photography, in its very essence, does not create something from nothing,” he said, “it is a device for copying existing images.” To him, copying the world and copying existing images amount to the same. In the series Accident (1969), inspired by Andy Warhol’s Death and Disaster series, he appropriated and rephotographed readymade images such as one of a car crash from a road safety poster, or pictures of accidents clipped from the popular press, including shots of television screens. He loves the coarse, pixelated appearance and the dense blacks of newsprint or monochrome TV, and he accentuated these traits by making some into oversized silkscreens on canvas. In Scandalous (2016), he used the same process but with pictures of celebrities and news stories.

In his provocative 1972 book Shashin yo Sayonara (Farewell Photography), Moriyama pushed the medium’s boundaries, choosing instinct over intellect to mix his own pictures with found amateur photographs or pictures printed from scratched or damaged negatives that had been rescued from the darkroom floor. As with the German artist Sigmar Polke’s work, there is a sense of both glee and violence toward the material. Moriyama cares less about the final result than the experimentation, the process. Looking at these abstracted images populated by ghostly silhouettes, with grainy blurs that might be dust or small explosions of light, I felt that his attempt was not so much a farewell to photography as a deeper engagement with the idea embodied in photo-graphy of “drawing with light.”

After a long hiatus, when he took no pictures, perhaps occasioned in part by his mother’s death in 1982, Moriyama challenged himself to a complete reset, abruptly changing method for his more meditative and intimate series Light and Shadow, which features lush hosta leaves, a flower (possibly from his mother’s garden), a sink, a pair of tires, boots, a hat. In this sharply focused series, there is faint echo of Tomatsu’s 1960s carefully composed still lifes of atomic disaster relics.

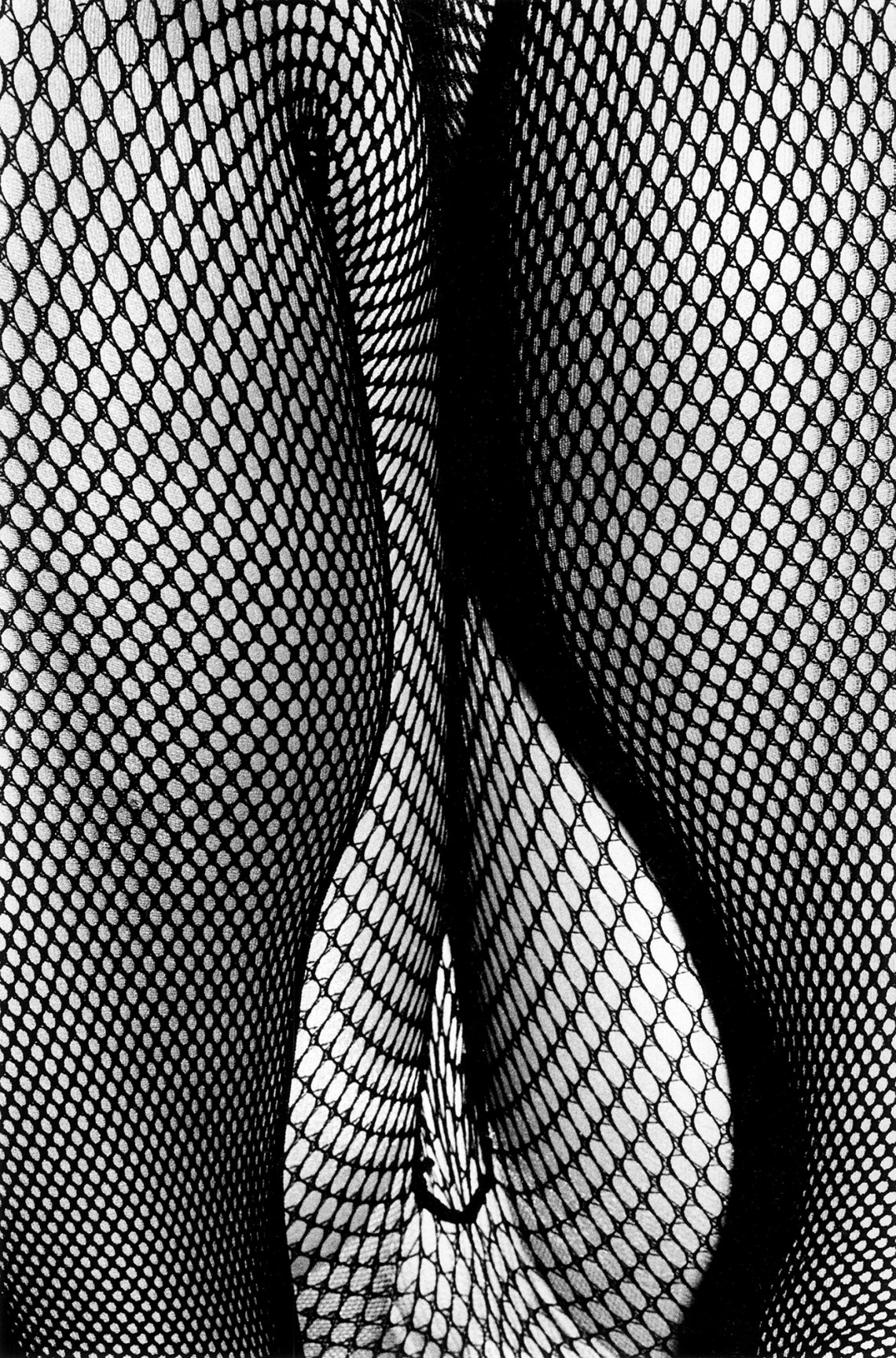

Photographing a woman’s legs encased in mesh stockings for his series Tights in Shimotakaido (1987), he composed extreme close-ups in color, which he then transferred to a stark black and white. The way this series is hung in the exhibition creates a hypnotic effect by repeating the same image in a frieze that occupies the whole length of a wall, drawing the viewer into a visual vortex.

In his recent Daido Tokyo series, Moriyama revisited Shinjuku, but this time in sharp focus and in garish, candy-like colors that echo Tomatsu’s use of color in his Interface portraits. Gone are the crowds of his earlier series; instead, here are empty plazas and back alleys, peeling posters and window mannequins, industrial pipes, jumbled electrical wires, a bum passed out on the street…all conveying deep loneliness and a sense of abandonment.

Beyond the differences between Tomatsu’s and Moriyama’s work, their common quest for a depth beyond appearances is what connects wise mentor and rebellious mentee. When they photograph Tokyo, they probe the night, pry open the city’s fault lines, and study its margins. But even as they do so, they are exploring the medium of photography itself, seeking its essence and stretching its limits.