When I called photographer Nan Goldin earlier this summer, she immediately asked if I might come out to her Brooklyn home for the conversation. Especially in these pandemic times, interview subjects try to keep reporters at a distance: a telephone chat or a Zoom call assures them safety, privacy, and more control over the process.

“No, I don’t want distance,” she told me. “How can I be interviewed without facing the person?”

Distance, in art and in life, is Nan Goldin’s enemy.

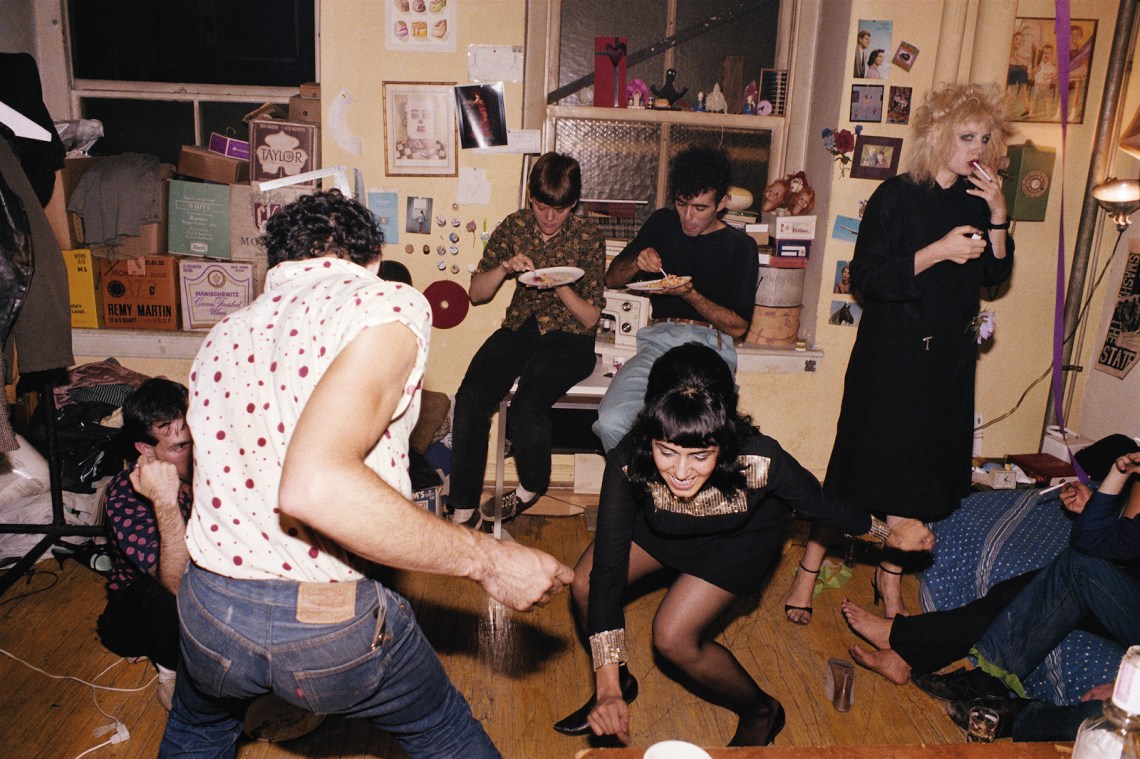

Over her half-century career in art photography (she is now sixty-seven), Goldin’s practice has involved total immersion in whatever she is documenting. No matter how difficult the subject—intimate abuse, cultural marginalization, addiction, prostitution, death—she has photographed it all emphatically in the present tense. “My work is my diary,” she likes to say.

Today, Goldin’s images hang in the Louvre, the Tate Modern, and the Metropolitan Museum, and next month Aperture is reissuing its edition of perhaps her most celebrated collection, The Ballad of Sexual Dependency (originally published in 1986). Next year, the Moderna Museet of Stockholm, Sweden, will host a retrospective of Goldin’s video pieces.

This, though, is by no means the only form of recognition Goldin currently enjoys. She has become a leading figure in the campaign for justice for victims of America’s opioid crisis, and a thorn in the side of the Sackler family—formerly best known as leading art world philanthropists but now notorious as the owners of Purdue Pharma and marketers of OxyContin, the addictive prescription painkiller widely blamed for fueling a national epidemic of opioid dependency. Goldin has used her standing in the art world to publicize the Sacklers’ reputation-enhancing efforts as major museum donors.

“Nan revealed a reality about this devastating crisis that made it impossible to look away,” the attorney Michael Quinn, who represented OxyContin victims in an action against Purdue Pharma, told me. “In her pursuit of accountability, she was able to shape a national conversation that the powerful—be it business leaders or politicians—preferred to ignore or even to bury.”

This aspect of her work naturally came to the fore of our conversations in her Clinton Hill apartment. What follows is a condensed and edited version of that dialogue.

Claudia Dreifus: As we speak, we’re now in the eighteenth month of the pandemic. How have you fared?

Nan Goldin: Personally, it hasn’t been too difficult. I’ve used the time for activism.

I’ve raised money for community organizations supporting the rights of trans people and for groups like VOCAL New York, which is changing laws on drug possession. Earlier in the summer, I raised $35,000 to buy the North Carolina Urban Survivors Union a spectrometer (that’s a machine that tests drugs to see what is in them). Right now, partly because of Covid-19, the drug supply is especially unsafe.

Another organization that I helped found, Prescription Addiction Intervention Now (PAIN), which advocates for survivors of the overdose pandemic, became for a while a party to the just-concluded Purdue Pharma bankruptcy case. That was a terrible experience—the bankruptcy judge hated us.

More positively, in recent months, I’ve picked up the camera again. I took some portraits. For a long time, I’d just been reworking my archive and creating exhibitions from that. I had stopped taking pictures of people. For a time, I was only interested in the sky. That was the only thing I felt a connection to. I photographed the way the sky changes every day. I didn’t have many relationships to people.

It was in 2014 that I became addicted to the opioid OxyContin.

How did that addiction begin?

I’d had wrist surgery while living in Berlin. One of the doctors gave me a high dose of OxyContin for the pain, pre-surgery. By the time I had the operation, I was taking ten pills a day. It’s a highly addictive drug. You can get hooked in only a few days.

I moved back to New York and started snorting it. It became my whole life. I had a dealer who’d come anytime, twenty-four hours a day.

Were you especially vulnerable to opioids because you had earlier recovered from a heroin addiction?

Yeah. If you have this history, the brain chemistry is set so that you respond immediately when opioids enter your system.

Let me say here, I’m not against opioids. And I think OxyContin is a great drug—for end of life and for cancer patients. But the marketing scheme of Purdue Pharma, the company that was owned by the Sackler family, resulted in these opioids flooding the country.

They aggressively marketed this highly addictive painkiller to all of America, and they pushed doctors and rewarded them for giving out OxyContin. They had great success marketing an earlier product, Valium, that way.

Advertisement

Purdue made enough OxyContin so that, theoretically, there could be a bottle in every single American’s medicine cabinet. It was all over the streets. Moreover, the Purdue leadership knew that OxyContin addiction had become an epidemic in the country. Their attitude was: How much will this increase our profits?

You know, when I use the term “epidemic,” I don’t say that lightly. The number of overdose deaths is something akin to the death toll from Covid-19: at least 800,000 Americans have died in the overdose epidemic, including more than 93,000 who’ve died during the pandemic.

I don’t mean to be insensitive, but how did you avoid becoming part of that statistic?

My life was saved by my friends and my assistants. I’m very close to my assistants. They got me into treatment. We spent a year trying to find a place to go to. There aren’t many good ones.

I finally went to the place where I’d gotten sober in 1988. That’s the McLean Hospital outside of Boston. I was there, in rehab, from January 2017 through March of that year.

I’ve been sober for four years now.

When did your activism against the Sacklers begin?

Nine months after I got out of the hospital. I was at the airport waiting to fly to Brazil to give an address. I had The New Yorker with me. While waiting, I read Patrick Radden Keefe’s astounding exposé of the Sacklers. It showed in detail how this one family, through aggressive marketing of these painkillers, made “billions of dollars and millions of addicts.”

Well, I knew of the Sacklers! They were philanthropists who gave to museums all over the world, including many that have my work. I thought, “I going to do something about this. I have to.” Then I thought, “Where do the Sacklers live? They live in their museums!”

I knew from experience how effective direct action by ACT UP had been during the HIV/AIDs crisis in the 1980s. In Brazil, I announced in my speech that I was going to “act up” about opioids and the overdose crisis.

When I got back to New York, I became like a moving train.

What was that train’s first stop?

The Met. The Temple of Dendur, which sits in the Sackler Wing. There’s a kind of river running around it. About a hundred activists snuck fake OxyContin bottles into the building. The bottles were labeled “Prescribed to you by the Sackler Family, major donors to the Met. Extremely addictive. Will kill.” We threw them into the river. It was beautiful.

In the next year, our group, PAIN, did “die-ins” to illustrate all the deaths from overdoses. In London, we did a die-in at the Victoria & Albert Museum, where there is a Sackler courtyard, to symbolize each of the people who’d died in England from overdoses.

Did these actions have much effect?

Not at first. And not at the V&A. There, the director declared he was “proud” to take Sackler money.

Nothing really happened for about a year. Then I made it known that if the National Portrait Gallery in London accepted $1 million from the Sacklers, I’d refuse to do the retrospective planned there. And they refused the donation! That same week, the Tate announced it would no longer take Sackler money. A day later, the Guggenheim did the same.

It became like a domino effect. The Met stopped taking their money. The Louvre took down their name. NYU changed the name of its biomedical school and took the Sackler name off their diplomas. Tufts took their name off five buildings—actually chiseled their names off!

In the end, we succeeded in pushing many museums to cut ties with them. The Sacklers were pushed off boards of directors and shamed in public; that’s very important to them. Isaac Sackler, the patriarch of the family, once told his three sons, “the most important thing is your name.” Well, we’ve changed the public meaning of their name from “philanthropists” to “opioid profiteers.”

Do you think your campaign would have been as successful as it’s been if you weren’t “Nan Goldin”?

It would not have been so effective without my name. My psychiatrist, who is very interested in these issues, thinks that there was no face to the opioid crisis, and to some extent I’ve tried to be that. But I think I’ve had a voice not just because I have a following but because I was addicted. I have credibility because I went through the experience.

Advertisement

Has this experience given you new insight into how the arts and culture are funded?

In America, there’s little public funding of these institutions. You always hear “the whole capitalist system is evil,” but that’s an abstraction. Now we’ve seen it play out up close.

There aren’t a lot of philanthropists who made their money ethically. Most big money is made at the expense of other people. Balzac said, “Behind every great fortune, there is a crime.”

What has your activism done for you as a person? How has it affected your art?

It’s given me so much. I think activism has kept me sober. In the recovery movement, they say you have to have some so-called higher power in your life. My higher power is my politics.

There’s no difference between myself as a person and as an artist. Whatever feeds me as a person feeds my work.

In October, Aperture will release the twenty-first printing of your signature piece The Ballad of Sexual Dependency. The book started out as a mixed-media slideshow that you screened in discos and clubs in the 1970s and 1980s. Did you ever think back then that it would become a classic?

No. That was a conservative time, and it was brave of Aperture to print that first version in 1986. Other photographers didn’t consider my work to even be photography. I got a lot of shit from male photographers. They said I wasn’t a good photographer, that my work had no meaning.

Why?

Partly because of sexism, and partly because I didn’t take black-and-white vertical pictures, which back then was the definition of photography. I was making color slides, which was radical. And then there was my subject matter, which made some people uncomfortable because I took pictures of myself and my friends and their sexuality.

Even deep into the 1980s, it was like that. At one point, MoMA was putting together a show called “Pleasure and Terror in Domestic Comfort.” Someone asked me and this marvelous man who represented me, Marvin Heiferman, to look at the selections. Marvin offered that there wasn’t enough pleasure in the show. I thought there wasn’t enough terror. I suggested they include my picture “Me, Battered.” [Full title: Nan one month after being battered.]

“We can’t,” I was told. “It’s not a good photograph.”

Really? That picture, a self-portrait taken after your then boyfriend had assaulted you, is now regarded as a masterpiece.

It’s one of the essential pictures that explains my whole body of work. It’s the key to it.

I had a problem with people not accepting my work all the way through the 1980s. That didn’t really change until the 1990s.

You said that Aperture was brave to publish Ballad. What do you mean?

Well, my father didn’t want me to publish. He thought it put the family in a bad light. The man who’d battered me certainly didn’t want it published. Aperture did it anyway, and I honor them for that.

Given the opposition, where did you find the strength to go forward with it?

I walk through my fear. That’s what makes me strong. If I want to do something, I’ll do it. It’s not the spoiled child syndrome, it’s just believing that I had to do it. I do things because I have to do them.

Your work has always been controversial—and still is. When I recently met a museum curator and told him I was due to meet you, I was so surprised when he said, “Oh, Nan Goldin: a lot of people think her work is exploitative.”

People have been saying that about me my whole life! It’s tired.

I know what I’m doing. There’s nothing exploitative about it. I photograph my friends! I don’t think of them as a marginalized group. Sometimes, people who haven’t met people like those in my photographs think they [my subjects] must be “outcasts” and “marginalized.”

People often compare your work to that of Diane Arbus. How do you feel about that?

Oh, man, they still do that? It’s the opposite of Diane Arbus.

I feel that Arbus was looking for somebody’s skin that she could wear. She stripped the people she photographed. She considered people freaks, which I’ve never done. Her work is not coming from the same empathy.

Maybe it comes from the same need to find out who you are, to find your identity. But it’s a totally different way of addressing it.

You know, when I first discovered her in 1972, I was really impressed. I brought her book home to the queens I was living with. They hated it. They hated her pictures of “transvestites.” They hated the way she stripped people.

Then I saw it through their eyes, and that nailed it for me. I’ve always lived what I’ve photographed. Most of the things I show, I did myself. And that’s the difference.

To return to the Sacklers, the Purdue bankruptcy case has, after two years in a Westchester bankruptcy court, just been settled. Among other things, Purdue Pharma is to be dissolved, and over a nine-year period the Sacklers will have to pay out $4.5 billion to the various states and creditors. They get to keep their personal fortunes, a great deal of which is held in offshore accounts. What is your take on the settlement?

It is corruption of justice. The Sacklers have been granted releases from any future litigation regarding the opioid crisis for themselves and for about a thousand of their companies, employees, friends—and all Sacklers, including those yet to be born, now and forever.

This shows that billionaires are above the laws of the nation and any moral accounting. The courts have failed us, Congress has failed us, the Department of Justice has failed us. All we have left is the museums to hold them accountable. Now, they have to take down the Sackler name. There’s no more time to wait.

Richard Sackler, the former president of Purdue Pharma, testified in the case unapologetically. He said that he and his family bore no responsibility for the overdose crisis. Would you have preferred he showed more contrition?

I’d hate to hear him apologize or “take responsibility.” Someone might actually believe him.

It would be meaningless after his years of controlling the whole empire. I know there are other victims who do want this. I don’t.

What do the survivors get out of the White Plains settlement?

Very little. One of the most egregious things about the settlement is that the claimants—of which I am one—will only see pennies. They will get amounts as low as $3,500 and up to a maximum of $48,000. People who were not prescribed OxyContin will get nothing—despite the fact the streets were flooded with that drug.

The payments are to be spread out over nine years, meaning that the Sacklers basically get to keep their capital. It’s not an immediate abatement, with this giant chunk of cash going to the injured parties, either: the larger portion of the money won’t be paid till the end of the settlement. During the trial, I heard an economist testify that the Sacklers will walk away from the settlement payouts richer than they are now.

Another thing: we’re concerned about the way state governments will use the money they get from the settlement. We worry about whether it will go to the communities where it’s most needed.

Is the settlement good for society?

It couldn’t be worse. It proves beyond doubt that there’s a different justice system for billionaires than there is for the rest of us. They won!

But we’re not done. A number of state attorney generals are appealing, and even the judge admits that this doesn’t release the Sacklers from possible criminal charges.

I hope that museums and universities will remove the Sackler name from their walls and wipe it off their virtual platforms now. Most of all, I hope people will not forget.

According to the settlement, in nine years’ time the Sacklers will get their naming rights back when they give a charitable donation. I hope museums won’t want their money badly enough to forget how the Sacklers got it. I hope the public won’t forget that legacy.

Despite the terrible ruling in White Plains, we did something important: we made the Sackler name synonymous with the opioid overdose crisis. We changed the narrative. That’s huge.

If you were to sum up your life to this moment, what would you say it adds up to?

I guess I decided as a child that I didn’t want to go through life without making a mark. I wanted to affect the world in some way. And I feel that, in some way, I did that. I did it through my work as an artist and through my activism.

So, in that way, I can be proud, except in the morning when I wake up. That’s when you question everything.

Anyway, I haven’t reached the conclusion. As disappointing as the White Plains settlement is, we’re not done yet. I’m not done yet.