This summer, I walked the lovely stretch of seaside along the coast road south from Tel Aviv to Jaffa. The ancient port city came into view for me on the hill ahead. In Arabic, we call it the bride of the sea. I remembered how my mother enjoyed smoking a cigarette only when sitting in a Jaffa café. The city was indeed a pearl, or, as I have described it before, a diamond-studded lantern rising from the water.

Over the past few years, I have tried to visit Jaffa periodically to follow developments in the city where my family lived until 1948, when, like many other Palestinian families, they were forced out. As I walk Jaffa’s streets and alleys, I try to imagine the city as it stood in my parents’ time and to envision the ways in which it has been transformed.

On my way, I stopped at Charles Clore Park, a sprawling recreation area by the beach named for the British financier who funded it. Its paved walkways, dog runs, outdoor art, and yoga stalls are all sited on what had been the thriving Palestinian neighborhood of Al Manshiyya, established in the 1870s, and which had a population of 13,000 in 1944. Al Manshiyya had numerous commercial and cultural attractions, the most famous of which was the busy Al’ansharah coffeehouse at the entrance to the neighborhood.

Today, on the inland side of the boulevard, glass towers rise high in the air. Not a trace remains of the Palestinian habitation that was there, except for the attractive Hassan Bek Mosque that stands in the midst of this sanitized, cosmopolitan landscape—and even this is under threat, from Israeli extremists who want to see it demolished. The latest of their regular assaults was in July when they threw stones, smashing windows.

When I reached the Ajami quarter, where the wealthy Yaffawis, as the people of Jaffa were known, had lived before 1948, I saw how far gentrification in the neighborhood had gone—a process that had radically altered its ethnic character. More and more of the attractive old Palestinian dwellings had been taken over, bought mainly by affluent Jewish foreigners. A few of the shabbier buildings still housed Palestinians who managed to hold onto their homes, though they have a hard time getting permits to do essential renovation work. A recent municipal ordinance requires protected tenants of rent-controlled apartments to buy the homes they live in—at the current exorbitant market price—or leave.

I grew up hearing almost too much about my parents’ life in that vibrant city by the sea. But beyond their laments, I knew little of what took place after they left, or even of my father’s persistent attempts to secure the return of the refugees. It was only last year, during the Covid-19 lockdown, that I finally opened the filing cabinet in my study in Ramallah where I kept father’s papers. For many years, I was too involved in my own work and felt reluctant to delve into my father’s affairs. But when I finally opened that cabinet, it was like finding a treasure trove.

There, I found the files in which my father, who was a prominent lawyer and politician, kept a record of his prodigious efforts as secretary of the Palestine Arab Refugee Congress to unify the Palestinian refugees and achieve the implementation of UN Resolution 194 for their return to their homes in Palestine. There were also files of his famous 1953 court cases against Barclays Bank, in which he succeeded in freeing the assets of Palestinian refugees kept at the bank’s branches in Israel, which the Israeli government had frozen. I also found an archive of his work to promote a plan for peace based on a two-state solution and the return of the Palestinian refugees, which he and other Palestinians in the Occupied Territories had drafted in the wake of the 1967 war.

*

Yet the memories I found in that cabinet were not all that connected the Jaffa of my parents to the Ramallah of my residence.

In 2008, a rabbi named Eliyahu Mali left with his wife and nine children from Beit El, a religious settlement next to Ramallah, and relocated to the Ajami quarter of Jaffa. There, he established an extremist Zionist enclave, which became a base from which he fanned intercommunal tensions in the city. His ultimate purpose was to make life for Jaffa’s Palestinian residents so uncomfortable that they’d be forced to leave. Writing about the campaign later, the head of the left-wing Israeli party Meretz on the Tel Aviv–Jaffa municipal council, Tamar Zandberg, wrote: “I am not sure that the city’s residents are aware of the move to Judaize Jaffa by Jewish settlers.”

Advertisement

This, though, was not the sole motive for the rabbi’s move. Mali has laid out this project in greater detail in lessons posted to the website of Ateret Cohanim, an Israeli Jewish organization that works for the creation of a Jewish majority in Jerusalem’s Old City and the Palestinian neighborhoods of East Jerusalem. For example, he asks his students:

You have no problem conquering the Temple Mount…eliminating the Mosque of Omar and starting to build the Temple, right? But someone who lives in north Tel Aviv will say, “Are you off your rocker?” He will tell you that your irresponsible behavior is putting the whole of the Zionist enterprise at risk…do you understand how they see it?

Reading this, it became apparent to me that the struggle to dominate East Jerusalem and the plan to demolish the mosque at Islam’s third holiest site was part of the same effort being conducted in Jaffa. Though infused by spurious religious references, Mali’s project is not an aberration in the history of Israel’s Zionist conquest, as the settlements all around where I live can attest.

Much has been written, both scholarly and anecdotal, about Israeli plans during and after the war of 1948 to empty historic Palestine of its indigenous people and settle Jews from around the world in their place. In an interview he gave to Haaretz, Adam Raz, the author of The Looting of Arab Property in the War of Independence (2020), concludes that: “The plundering was a means to realize the policy of emptying the country of its Arab residents.” I thought of this as I read in my father’s papers how urgent he believed it was to restore the refugees to their homes quickly, before they lost all the possessions they’d left behind and have to return to houses empty of all furniture.

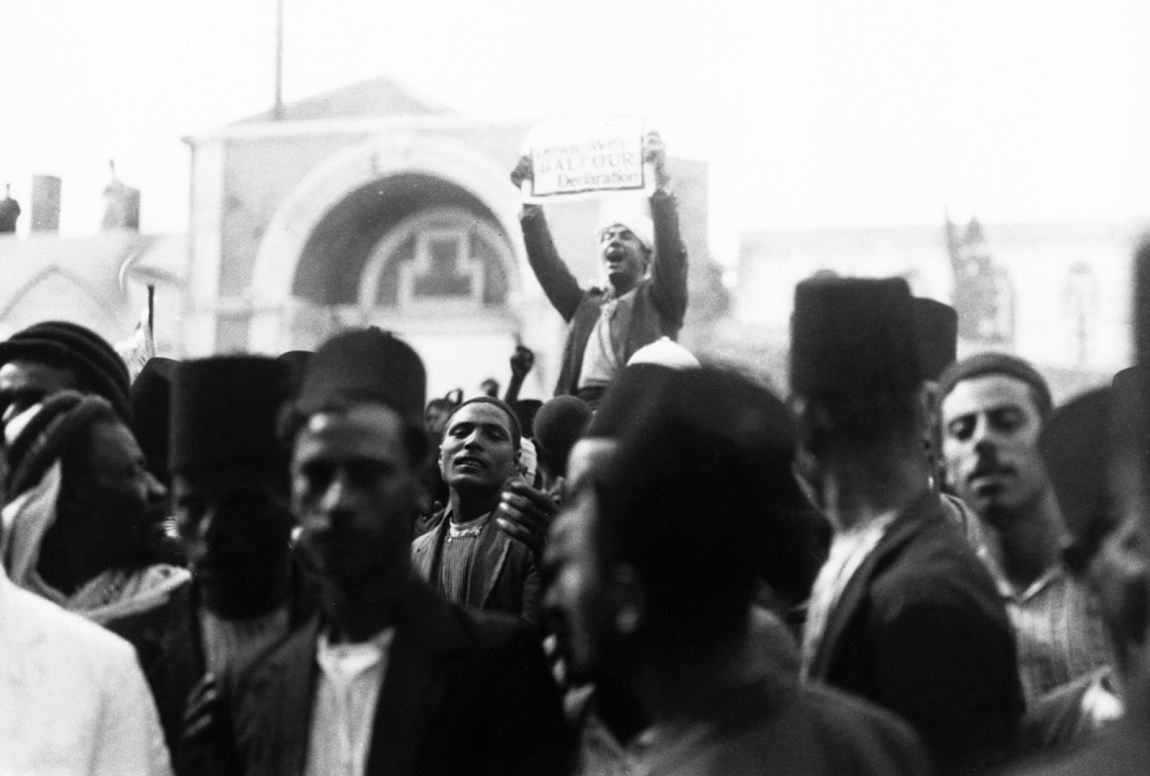

Israel’s leaders had it all figured out. A persistent myth, in fact, is that the Zionists accepted the 1947 partition plan proposed in UN Resolution 181; the kernel of truth that allows that misrepresentation is that the Arab states rejected it. It turns out that there is not a single official document attesting to Zionist leaders’ approval of the plan; indeed, there was vehement opposition to it from the Zionist right, which believed the division of what they considered their homeland a historic crime.

In practice, the Zionist militias and, later, the newly formed Israeli army managed to take over territory well beyond what the UN had granted the Jewish state according to the partition plan. And this included Jaffa, which was designated Arab territory under Resolution 181. Yet the Jewish forces of the Haganah and Irgun took it over and drove out almost all of its 70,000 Palestinian inhabitants, leaving a remnant of only about 2,000.

“We left without bringing anything from our house in Jaffa,” my mother would tell me. “We thought we were staying for two weeks. We didn’t even bring warm clothes to protect us from Ramallah’s bitterly cold winter.” And in my father’s cabinet, I found the keys to both his office and his home. Though they were never again to be used, he had held on to them all those years.

With the acquiescence of the British, who had governed Palestine under UN mandate since 1923, the territory came to be divided between Israel and Jordan. On December 1, 1948, at the Jericho Conference convened by King Abdullah of Jordan, my father voiced his opposition to the unconditional annexation of the West Bank to Jordan. As I learned from my father’s papers, in his capacity as secretary of the Palestine Arab Refugee Congress, he and other Palestinian leaders worked on unifying the Palestinian refugees as they tried to ensure the UN Resolution 194 on the right of return was implemented. Their efforts came to naught: the United Nations Relief and Works Agency was created to provide humanitarian aid to the Palestinians forced from their homes, but its simultaneous effect was forever to deny their right to be recognized as refugees under the Refugee Convention of 1951.

To relieve Israel from the accusation that it had practiced ethnic cleansing in the conflict of 1947–1948, its propagandists spread another lie: that it was the Arab nations, not Israel, that had called on Palestinians to leave Palestine. With the passage of a few generations, wagered Israel’s first prime minister, David Ben-Gurion, the Palestinians would have forgotten all about their former country.

Advertisement

Evidently, this did not happen.

*

I still recall how, back in 1989, as I stood in the military court in Ramallah’s British-built Tagart prison where I was defending a young client, I felt I was dreaming. I couldn’t believe that the proceedings I saw and heard that day were real—as the petitioner, an Israeli settler with a Russian accent, complained of her car’s being stoned by Palestinian schoolgirls as she drove to work.

Nowadays, when I look at the tremendous transformation that has taken place all around me because of the establishment of Israeli settlements, I know I’m not dreaming. Reality seems to have caught up with me.

Three decades on, the Israeli military court is no longer in the heart of Ramallah but has been moved to the city’s outskirts. The compound, with its accompanying detention center, is now located in what Israel calls Ofer, once one of the most attractive areas near Ramallah, where the water draining from the low plain used to form a pond where birds migrating north would stop for sustenance. Nearby is the sprawling settlement of Giv’at Ze’ev, one among some three hundred Israeli settlements that have entirely transformed the landscape in the small area of the West Bank.

Does this mean that things are as they are, and there is no possibility for change—whether from within or without Israel?

In an essay in The Guardian after Israel’s bombardment of the Gaza Strip in May, the Israeli human rights lawyer Michael Sfard noted that, for a long time, progressives had seen the Israel–Palestinian conflict as comprising two separate parts: a democracy in Israel and an occupation across the Green Line (as the 1949 armistice border is known). But now, he wrote, it was no longer possible to deny both the blatant apartheid in the West Bank and the effort to maintain Jewish supremacy within Israel proper. As he concluded:

The updated paradigm uses a lens that reveals an Israeli ethnocracy and therefore makes the forging of a shared Palestinian–Israeli vision possible—a vision that respects the national aspirations of both peoples, and guarantees equal rights to everyone living in the land.

A similar shift is apparent to the anthropologist Lori Allen. In her book A History of False Hope: Investigative Commissions of Inquiry in Palestine (2020), she surveys the failed initiatives of the past: some twenty international commissions convened over time on the question of Palestine, all of which failed to hold Israel to account. Yet she believes that the commission of inquiry that the UN Human Rights Council voted to establish on May 27 of this year to report on violations in Israel, the West Bank, East Jerusalem, and Gaza is more promising, thanks to emerging new political circumstances. Allen writes that these include “a resurgence of international legal and activist efforts to challenge Israel’s systematic abuse and dispossession of Palestinians across the occupied Palestinian territories, Israel, and the diaspora—including efforts among Jews.”

Then there is the International Criminal Court, whose efforts Israel and the US are trying to curtail. But after a long delay, the ICC is now investigating allegations of war crimes committed by Israeli generals and officers (the ICC is also examining military actions conducted by Hamas, the Palestinian group that governs Gaza).

After his piece was published, Michael Sfard wrote to me. “It took me several hours to write it,” he said, “but I now understand that, in some way, all my life prepared me for it.” That is a feeling I can recognize.

After going through my father’s papers in that cabinet that had remained shut for so many decades, it was clarified for me that his two main struggles—in his words, for “achieving Palestinian self-determination” and “recognition of the right of return”—remain unfulfilled. These struggles are my patrimony; indeed, they belong to all Palestinians and the generations to come.

But there was another facet of his experience I’ve inherited. And that is the fear of another, impending Nakba. I recall the anguish with which my father used to tell me that if things continued as they did, with more and more Israeli settlements being built, there would not be a plot of land left on which to bury our dead, let alone one to live upon.

Ramallah is surrounded by three settlements inhabited by Jewish settlers who believe the land is theirs alone. Psagot, to the east, is inhabited mainly by racists of French extraction with belligerent views of Palestinians; Beit El, to the north, where Rabbi Eliyahu Mali lived before he moved to Jaffa, is home to extremist religious Jews; while Dolev, to the northwest, is where an Israeli High Court judge lives. In addition are numerous other outposts where the most militant settlers live.

I have good reason to be worried. Over the past year, hardly a week has gone by without some act of settler violence—whether the destruction of an olive grove or orchard, or a physical attack on a person or Palestinian home nearby. Naturally, the settlers are armed and backed by the Israeli army, while the Palestinians have no such official ally. It is not at all hard to imagine ethnic cleansing or a massacre taking place.

This year, Palestinians might at long last have made substantial progress in regaining their right to determine their own history. Let us hope this will help us achieve a just outcome of the Palestinian struggle, rather than a second Nakba.