On a Sunday in the summer of 1970, we were all herded up to the little church in Cúil Aodha for Mass. We were city kids sent to this small and remote village in County Cork to learn Irish from the native speakers. Their little chapel was gray, pebble-dashed, with no steeple, more like a hall than a chapel. Someone said the church was called Saint Gobnait’s and I sniggered at this with another twelve-year-old Dublin boy. It was such a stupid redneck name. You just had to say it to know there was something backward about these country people—gub, nit. We were marched up to a low balcony at the back of the church. I was literally looking down on the country people on their wooden benches, across at the plain painted walls, up at the unadorned wooden ceiling. White light came in through the rows of narrow, oblong windows on both sides.

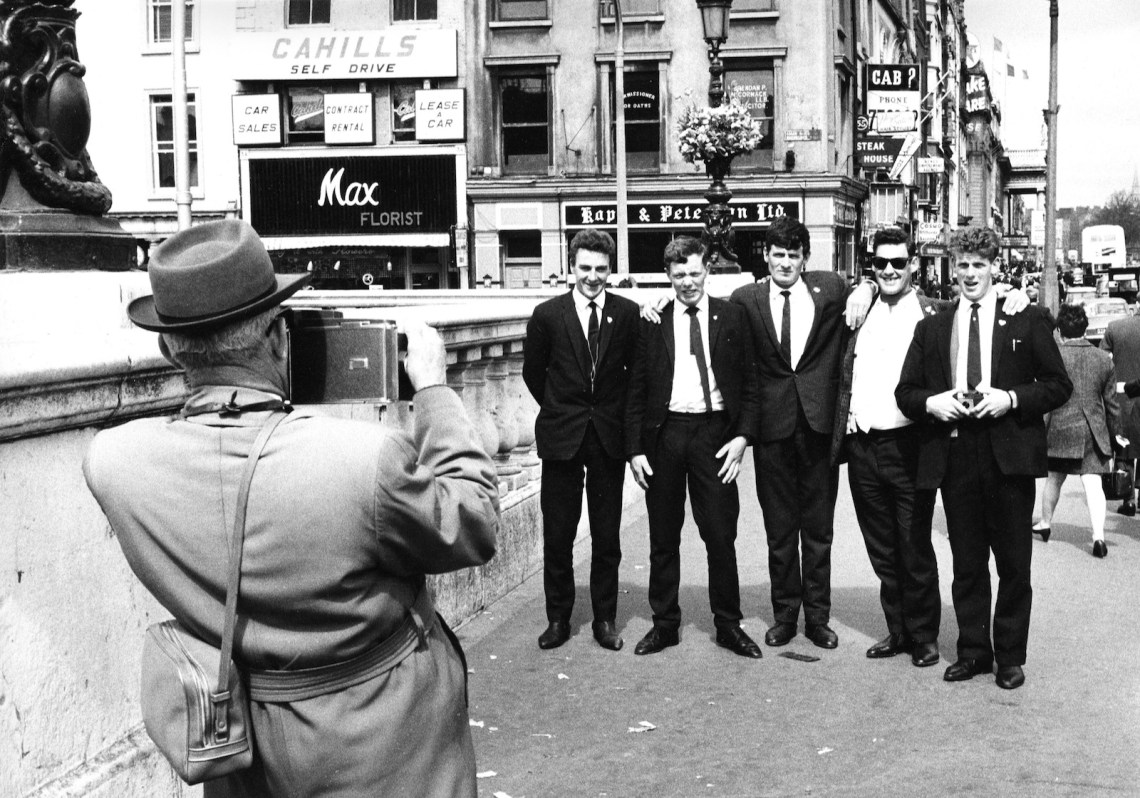

There was a small organ and two or three rows of stalls that filled up with men and boys. They all wore white shirts and black trousers that made them seem, in that time of male flamboyance, austere, even ascetic. A man sat down at the organ. He kept one hand on the keyboard and with the other began to conduct the choir. I knew enough Irish to know that the words were those of the Our Father, words flattened by repetition into meaninglessness. But the melody was like a meandering river, slow and serene yet utterly implacable.

The man at the organ was the composer Seán Ó Riada and the choir was singing the Mass he had written for them after he moved to Cúil Aodha in 1963, using the traditional airs of the region. It was not like any music I had ever heard, mostly because it seemed not to be trying to do anything at all. Pop songs or classical symphonies or the folk ballads of the cities were out to capture your attention, to stir your emotions, to tell you a story, to make you laugh, to honor the martyrs. This music had no interest in staking any claims. It just enfolded you within itself. That gave it an immense dignity.

I couldn’t place it. The choir was all male, but it did not sound masculine: the voices were nasal and high-pitched but restrained, declining to strain for effect. The melodies were long and linear and seemed, because they were sung in unison, utterly simple. But as you listened, they released themselves into gentle, unshowy ornamentations and then curved back into line. The Irish words were at once guttural and baroque. It was all as plain as the church itself, but it also had the assurance of high art.

I had, at that time, become deeply bored by Mass. I had long given up my career as an altar boy. I had not yet found the courage to stop going on Sundays, though I knew I would if I could. But as that sound washed over me and pulled me in, I felt that there was something supernatural at work. I wasn’t sure if it was God as I knew him, but then maybe this was what God might be: this music, these country people, the chant of their responses in Irish, the light falling on the white walls. Up on the balcony, I felt as if I was no longer looking down on it all, but that it was rising toward me.

On the way out, after Mass, I noticed that over the door of the church was written in old Irish script Tá an Maistir Annso—the Master Is Here. I knew what was meant by it, but it also seemed to me to refer to Ó Riada, and that in any case there was not much of a distinction between these masters. I later heard people say that when he had first written his Mass and performed it with the choir, some of the congregation were not happy. Not because it was not beautiful but because it was so beautiful that it distracted them from their devotions.

Ó Riada’s presence in Cúil Aodha was exotic. He hunted and fished. He had a genuine Irish wolfhound. But in his own eyes, he was going native. He had been a European art composer named John Reidy. As a student, he played jazz piano for fun and began to write music in the manner first of Debussy, then of Stravinsky, Schoenberg, Webern, and Berg. He had no interest in traditional Irish music. He adored James Joyce, smoked French cigars, and wore a beret. He wrote a setting of Ezra Pound’s Lustra. After graduating from university in Cork, he performed his solo piano pieces on RDF, the French national radio station.

Advertisement

It was only in the late 1950s that he became fascinated by Irish music, and in particular by the unaccompanied sean nós (old style) singing that he heard in the the Irish-speaking areas of Kerry. In 1959 he composed the music, based on traditional airs but scored for classical orchestra, for Mise Éire, a documentary film telling—from a nationalist perspective—the story of Ireland’s fight for freedom. Although I had no idea he’d written it, I already knew some of this music—its big, swelling theme, “Róisín Dubh,” was part of the soundtrack of my childhood. He also created a group, Ceoltóirí Chualann, to play traditional Irish dance tunes and laments as if they were chamber music. It later evolved into the Chieftains.

As Seán Ó Riada, John Reidy was now virtually the state’s official composer. He was even commissioned by RTÉ, the national broadcaster, to write two works that would be used upon the death of the former taoiseach (prime minister), Éamon de Valera, in 1975. But he came to think that being properly Irish meant turning away from his roots in European art music. He formalized this breach when he moved from Dublin to Cúil Aodha in 1963—he would speak Irish and work in an Irish idiom.

This turning inward was one answer to the problem posed by Ireland’s still tentative embrace of international modernity. Ó Riada, like many young artists and intellectuals, did not see the opening up of Ireland’s economy to foreign investment in the 1960s as a liberation from repression and stasis but rather as the selling out of the country and its tradition. Shortly before he moved to Cúil Aodha, he wrote angrily in The Irish Times:

The country that was won by such costly sacrifice, that was bought with the blood of good men, is being sold, physically, spiritually with its people, by its people, for the customary thirty pieces of electro-plated nickel silver. This is more than a scandal, more than a disgrace. It is the betrayal of every man who through the centuries took up arms for this country’s freedom.

He began to invoke An Naisiún Gaelach, the Gaelic Nation, a revitalized version of the early-twentieth-century nationalist ideology, which argued that Ireland must be, in the words of the Easter Rising rebel Patrick Pearse, not merely free but Gaelic as well. It would not have bothered him that this nation could not include Protestants in Northern Ireland. Ó Riada’s wife, Ruth, “had difficulty restraining him in 1969 when the Northern troubles broke out in earnest, as he very much wanted to take his gun and fight for his own Gaelic nation on the barricades of Belfast.”

But Ó Riada wanted both to reject commercial modernity and to enjoy its fruits. He fantasized about building a large hotel on the banks of the local river, the Sullane, with an airport beside it to bring tourists into the area to hunt and fish—and listen to his music and that of the local singers. That, presumably, would also have “sold” the old Ireland he loved. The easy opposition of good tradition to bad modernity was a refuge from reality, not a way of living.

Neither, though, was Ó Riada a phony. His respect for the oral and musical cultures of rural Ireland was genuinely deep and, as I experienced that morning, he gave that culture a moving sense of its own dignity. But he was trying somehow to answer a question that was at the heart of the dilemma for Ireland in the twentieth century: Did it have to be destroyed in order to be saved? In his 1969 play The Mundy Scheme, Brian Friel asked, “What happens to an emerging country after it has emerged?” In the play, which ran at the Olympia in Dublin, the minister for finance discovers that the country has run out of money and is “on the point of national death.” The bankrupt government comes up with a scheme to sell the West of Ireland to a New York property developer as a giant graveyard (“the world’s resting place”). The satire was heavy-handed, but Friel was returning to a sense of morbidity that had been seen as demographic by politicians and that was cultural for many artists and intellectuals a decade later.

And yet in 1970, the same year that I was encountering Ó Riada’s almost mystical power in Cúil Aodha, a census was taken. Published the following year, it revealed two epoch-defining facts. One was that for the first time in Irish history, a majority (52 percent) of the population was living in towns and cities. The other was that almost half of the population was under the age of twenty-five. Ireland was an urban country and a very young country. Since, as a city boy, I belonged to both of these categories, was I not as authentically Irish as an elderly grandmother living in a cottage up a mountain?

Advertisement

We had an equal and opposite prejudice. In the city, the rural world was obviously inferior. We all watched—because there was nothing else to watch—RTÉ’s rural soap opera, The Riordans, set on a family farm. Though a brilliant and pioneering series, its main draw for us kids in Dublin was the accents, which we loved to mock. The son was called Benjy—the worst insult we traded with each other was to say to another kid: “Will you get up the yard, there’s a smell of Benjy off ya.” We made up funny sentences: “Julie Riordan, where do be she?”

The underworld of ancient, pagan belief that persisted in Ireland before television had become an absurdist joke. Shortly after eleven o’clock on the night of December 8, 1962, about sixty young men and women crushed around the door of the police station on College Street in the center of Dublin. Many of them pushed inside and “began a systematic search under the tables, chairs and benches.” They claimed there were leprechauns in the station and “they just had to find them.” They had been convinced of their existence by a French hypnotist, Paul Goldin, whose show was playing at the nearby Olympia Theatre. As the Sunday Independent reported:

The grand climax to his arduous performance came when he seemingly convinced his ‘pupils’ that they had each just lost a leprechaun and as the curtain came down a group of docile young folk suddenly erupted into a wild scramble around the theatre searching for their lost leprechauns.

This was what the desire to reconnect with a Gaelic past could look like if you were an urban Irish kid: a hypnotized search for lost leprechauns. One of the reasons the experience of encountering Ó Riada in the church that morning was so overwhelming for me was that, as well as making the Mass seem beautiful again, it showed there was something more to it. The desire for connection was given meaning by the reality that there was still something to connect to, traditions of music and singing and storytelling and language that had their own highly distinctive texture.

The odd thing is that, for a large part of that half of the population who were under twenty-five, the dilemma of whether to try to relate to these indigenous traditions or embrace international consumerism was partly solved by an unlikely cultural force: the rise of the hippie. Hippies didn’t look like Ó Riada in his tweeds, but they were following the same compulsion—the desire to escape urban modern life, the allure of indigenous wisdom, the dream of getting back to the garden, the return to a primal innocence before the corruptions of capitalism.

In the summer of 1972 I got my first job, working in Dunnes Stores. I saved up my own money and, for the first time, I was able to buy some clothes for myself. I chose a pair of luscious purple seersucker trousers with thirty-two-inch flares, an orange shirt with huge white flowers blossoming all over it, and a lurid green tie that was almost as wide as the flares. I couldn’t get over how beautiful I looked. I was a child of the universe.

It is hard to fathom that for us the big conflict of that era was not the emerging disaster north of the border. It was hair. The idea of letting it grow contained within it every possible kind of growth—from darkness toward enlightenment, from square to hip, from childhood to adulthood, from dependence to independence. Its importance was total. The proudest moment of my life to date was when, one day that summer, instead of going to the barber in Crumlin I climbed up the stairs over the China Showrooms in Grafton Street to Herman’s Klipjoint, Ireland’s first unisex hair salon, opened by a Dutchman, Herman Koster. There were chocolate-brown walls and orange chairs. “Brown Sugar” was blaring from the stereo. The cutters were all girls and they wore blue jeans and kaftans. It was heaven.

It was also trouble. The Christian Brothers, the lay Catholic order that controlled the schools that most of us attended, declared war on long hair. In September 1970 fifteen pupils at the De La Salle secondary school in Skerries were sent home because of the length of their hair. Then 120 students were turned away from two other secondary schools down the road from us, for the same reason. What the Brothers could not grasp was that the desire to be hippie-ish was actually encouraging us to take an interest in the very thing they supposedly wanted to promote: the idea of a distinctive Irish culture.

This paradox was beyond them, but for us it was potent. What made it so was the idea of the Celtic, a word that carried vague but powerful associations of ancient wisdom and timeless authenticity. One of the odder effects of the explosion of youth culture in the 1960s and early 1970s was what might be called a second Celtic Revival in Ireland. In the search for an alternative, anti-establishment aesthetic, the notion of a pre-Christian Celtic world promised a kind of authenticity that dovetailed with the international counterculture. It manifested itself in everything from jewelry to the invention of “Celtic rock.”

Not long after I got back from Cúil Aodha, one of the regular passengers on my father’s bus route, Lily Shanley, who was front-of-house manager at the Abbey, gave him tickets for a production of Macbeth starring Ray McAnally and Angela Newman. It was the first time I had ever seen a play and I was enthralled by it. The visual trademark of the production was that it was a Celtic Macbeth. The men were got up as Celtic warriors. The designs were full of Celtic spirals and triskels.

With all of this swirling around, I went to the library and borrowed a copy of Augusta Gregory’s Cuchulain of Muirthemne, a 1902 retelling of the Táin Bó Cúailnge (The Cattle Raid of Cooley) cycle of legends, describing the mythic conflict that erupts when Queen Medb of Connacht invades Ulster to capture its most prized treasure, a great brown bull. Ulster is defended by its youthful champion, Cúchulainn. This stuff from the first Celtic Revival now seemed exciting again. It belonged to us, it was ancient and indigenous, but it also sat very comfortably with what Phil Lynott’s Thin Lizzy were doing in Vagabonds of the Western World, and indeed with the hippie mysticism of Led Zeppelin’s “Stairway to Heaven.”

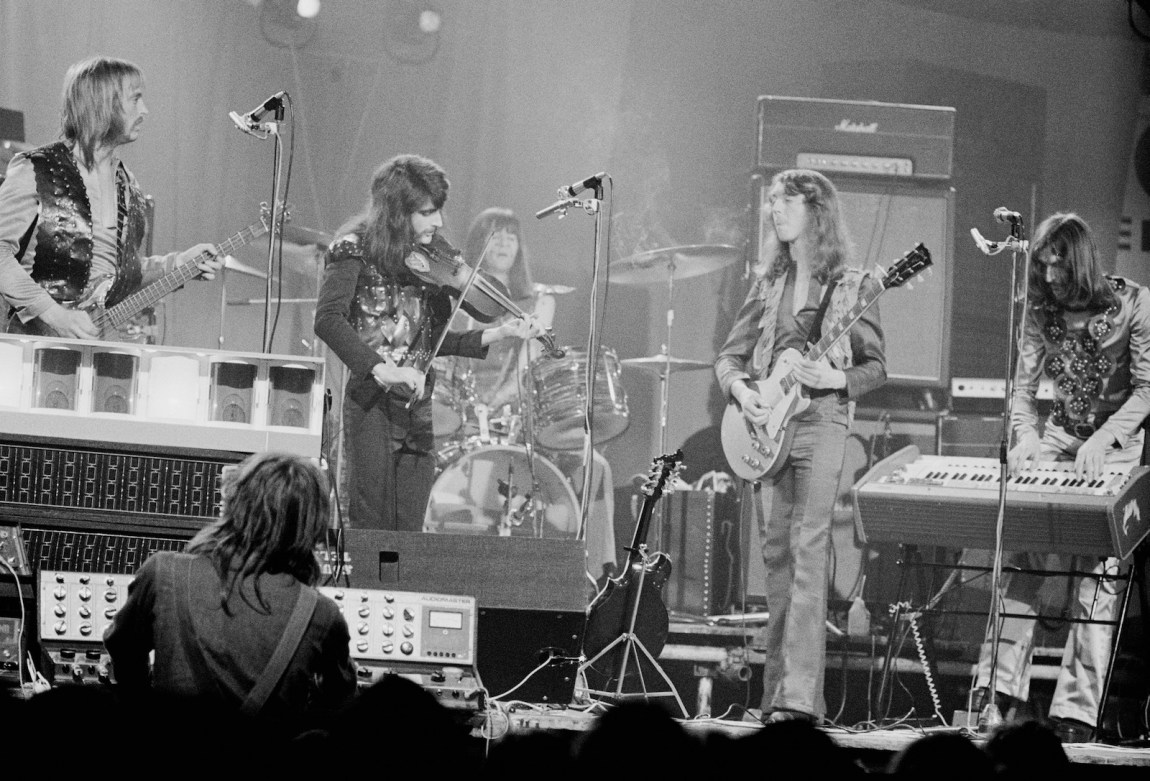

The most electrifying invention was the Celtic Rock band Horslips. It was somehow perfectly representative of where we were. On one level it was entirely ersatz. It was formed in 1970 by an advertising agency in Dublin that needed a rock band for a TV commercial. Three of its own staff played band members. But they needed a keyboard player, and somebody knew Jim Lockhart, who was an accomplished multi-instrumentalist with a strong interest in both classical and Irish traditional music. Lockhart in turn was a follower of Séan Ó Riada, with ambitions to synthesize these two forms. When they decided to form a real band, they brought in Johnny Fean, who grew up playing banjo and mandolin in traditional music sessions in County Clare before falling under the spell of Jimi Hendrix. It all came together in a line-up kitted out in glam rock gear playing loud electric versions of Irish and Scottish dance tunes alongside their own riff-heavy compositions.

It couldn’t have been more phony and it couldn’t have been more real. How could this strange brew make any sense? All I knew was that it made more sense to me than anything else did. I saw Horslips at a concert in Dublin’s Baldoyle racecourse in May 1972, and when they started playing, they sounded to me not just normal themselves but a revelation to me of my own normality. Their yoking together of American rock and roll and Irish traditional music expressed exactly the way many of us were living. And it was not a cacophony. It worked. They were able to hold it all together, to keep it going, to make it hum with energy. I loved them for this, absolutely and unconditionally. I got a Horslips poster and put it up over my bed. I went to as many of their concerts as I could afford. When they released their concept album version of the Táin, I was there for its first live performance. Afterward I bought a copy of the album and the 1969 translation of the original myth by the poet Thomas Kinsella, wonderfully illustrated with abstract blot drawings by the painter Louis le Brocquy.

This was cultural escapology. You didn’t have to choose. Not between modes—high or low, kitsch or serious, contemporary or ancient. But more importantly, not between here and there, Ireland and the world, tradition and modernity. The great sin, cultural as well as religious, was impurity. But being impure seemed just fine in both dimensions. That was not how it seemed to Ó Riada or to those who felt that salvation lay in the search for a lost authenticity without which Irish lives would be valueless.

In October 1971 I heard the news on the radio that Seán Ó Riada was dead. The announcer did not say that his death certificate named the cause of death as “cirrhosis of the liver, caused by alcohol.” He was two months past his fortieth birthday. Hundreds of cars followed the hearse from Cork to Cúil Aodha. All the shops were shut along the road and all the children came out from every school to stand and see him pass. His body lay in the little church where I had watched him conduct his Mass. The future taoiseach Charles Haughey and other prominent figures traveled to the funeral. His choir sang a Requiem Mass of his own composition, with his sixteen-year-old son Peadar taking his father’s place at the organ. Giving the oration, the poet Seán Ó Riordáin said that Ó Riada had connected people to “an rud a aontoinn sinn leis an dream a tá curtha I gcre na cille seo agus i gcre gach cille in Eirinn”—the thing that unites us to those who are laid in the clay of this churchyard and in every churchyard in Ireland. I didn’t really think so. I thought he had connected me to something that was very much alive.