Whenever I drive through New Hampshire, my attention is drawn to the motto that appears on the license plate of every car registered in the state: Live Free or Die. Affixed to plates beginning in 1971, these words were first uttered in 1809 by New Hampshire’s leading revolutionary war hero, Major General John Stark, as he remembered his part in the 1777 Battle of Bennington in nearby Vermont. His phrase, then and now, echoes the 1775 empire-shattering cry of Virginian Patrick Henry, “Give me liberty, or give me death!”

Republicans today claim to be the guardians of America’s freedom-loving inheritance. To the GOP, liberty means protecting individuals from government overreach, much as their forebears sought to free America from the tyrannical grasp of George III. They want to limit the power of the federal state and deny it the fuel on which it runs: taxation. Senate Republican leader Mitch McConnell and his legions are certain that their conception of liberty—which holds that freedom can only flourish when a central state is small, distant, and weak—is the one true political tradition to have emerged from the American Revolution.

But the Democrats are themselves heirs to a revolutionary tradition, one that the identifies the source of tyranny not as government but as private concentrations of economic power. Suspicion of corporate dominance and extreme levels of personal wealth has made the charge of “monopoly” resound across the nation’s history. Anti-monopolists wanted to break up corporations or reduce their power while redistributing the ill-gotten gains of “plutocratic” fortunes to the middle and working classes and to the poor. The goal, often achieved through a progressive taxation scheme that targeted the superrich, was to level the economic playing field and give every hardworking farmer, laborer, or small business owner a fair shot at success. The pursuit of liberty, let alone happiness, in the American Republic required nothing less.

This anti-monopoly tradition is not a “truer” expression of American revolutionary purpose than the anti-tax, small-government one. Rather, each embodies an aspiration that took shape during America’s founding moment and that has charged the country’s politics ever since. The anti-tax tradition, which birthed the Reaganite version of modern Republicanism, has been ascendant these last few decades. But powerful forces unleashed, first, by the Great Recession and, more recently, by the Great Pandemic have scrambled the political landscape, allowing the anti-monopoly tradition to reemerge and bid for influence once again. This resurgent anti-monopoly movement nurtures a very different attitude toward government, contrasting sharply with the posture of the anti-taxers. Indeed, taxation is one, crucial instrument in its armory.

*

As they mobilized against the tyranny of the British Crown, members of John Stark’s and Patrick Henry’s revolutionary generation nurtured suspicion of all governments, distant or near, deemed a threat to American liberty. The framers of the Constitution grasped this fear of concentrated public power, which is why they limited the authority of the federal state and dispersed its powers across several branches and levels of government. These measures did not suffice, however, to snuff out anxiety that America’s new government would, like the British monarchy, seek power beyond its remit. America’s central state, impoverished by war, had incurred large debts that had to be repaid. Moreover, new revenues were needed to raise militias and armies to contend with those perceived as threats to the new republic—the indigenous peoples living in its midst, and the imperial outposts of Britain, France, and Spain on its borders. To pay its expenses, the American state taxed its people, as the government of George III had once done.

The imposition of taxes soon sparked revolts against government overreach. The battle cry “No Taxation Without Representation,” first hurled against the British Parliament in the 1760s, persisted into the 1790s, this time targeting America’s own government, sitting in Philadelphia. A huge, armed anti-tax movement called the Whiskey Rebellion erupted in western Pennsylvania, its members refusing to pay a tax that the federal government had levied on their spirits. George Washington subdued these insurrectionists, but the army of 13,000 required to do so revealed how deep ran the popular conviction, inherited from the colonial era, that a central state and its taxation scheme threatened American liberty.

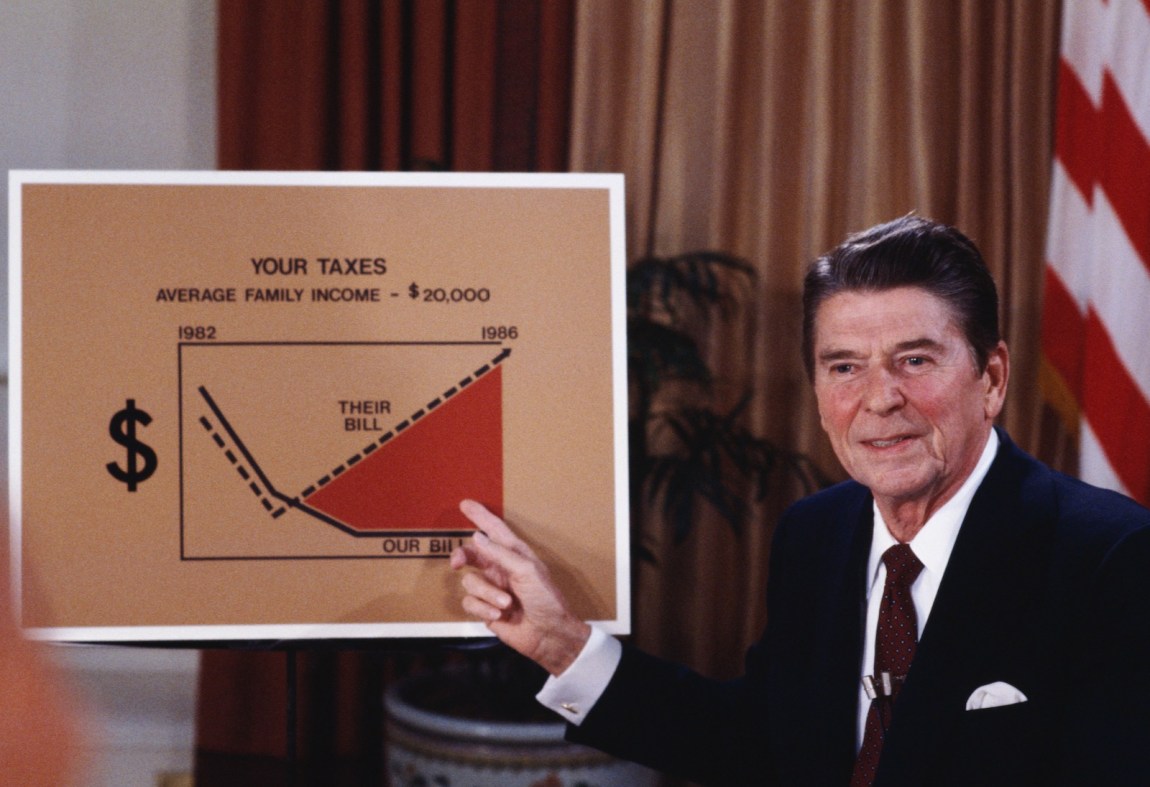

The animus against federal power runs like a red thread through the history of the nation from that time forward. It propelled Andrew Jackson’s 1830s campaign to destroy the Bank of the United States, and the efforts in the 1870s and 1880s to strip the federal government of the powers it had gained during the Civil War and restore “states’ rights.” It ebbed for the first two thirds of the twentieth century, but then resurged in the 1970s and 1980s as Ronald Reagan framed “big-government” Democrats as enemies of liberty and made the welfare state the bane of the GOP. In defining liberty as freedom from government, Reagan claimed to be channeling the true legacy of the American Revolution. So did his contemporary Meldrim Thompson, the conservative activist turned governor of New Hampshire, who claimed credit for emblazoning the motto Live Free or Die on the state’s automobiles. The surest way to stymie a grasping, overweening government, both Reagan and Thompson declared, was to strip it of the tax revenues that were its lifeblood.

Advertisement

And so the red thread continued. The anti-government and anti-tax disposition that returned with Reaganite vengeance in the 1970s and 1980s fueled Newt Gingrich’s Contract with America in the 1990s, the Tea Party’s assault on Obamacare in the 2010s, and, in part at least, the anti-vaxxer insurrection of our own time. Grover Norquist, a key architect of the small-government, anti-tax outlook that defines the modern GOP, delighted audiences by telling them that he wanted to shrink the size of the federal government until he could drown it in a bathtub.

*

There is, though, that second strand—a blue thread, we might say—that runs, braided, through American history. In the eighteenth century, the charge of monopoly—as well as unjust taxation—was laid at the feet of George III. Anti-monopolists focused attention on the threat that concentrated economic power posed to personal liberty. The king, like most monarchs of his era, had issued charters that granted certain individuals or firms exclusive rights to manufacture, trade, and transport goods, to possess land, and to handle currency. These charters were meant to privilege those who had won royal favor (usually in return for a promise that a share of the profits would be funneled to the king or queen). The existence of these Crown-sanctioned enterprises had long angered colonial Americans, for reasons of both principle and pique. The principle was that markets ought to be open to all competitors, not rigged so as to advantage a select few; the pique, that the Crown bestowed many more of these favors on those living in the imperial metropole than on those residing along the British Empire’s North American periphery.

Vestiges of this rigged political economy survived the American Revolution, which is why new movements arose in the early Republic to reinvigorate the work of constructing an economy built on the ideal of fair and free competition for all. By the 1850s, America had successfully eliminated government-sanctioned monopolies in the Northeastern and Midwestern states, the regions driving the nation’s industrial revolution. The Civil War and the destruction of slavery in the Southern states, it was hoped, would spread conditions of sound competition throughout the land. A nation consecrated to “free soil, free labor, free men,” a slogan often invoked by the Republican Party across its 1850s and 1860s ascent, seemed to be winning the day.

But then a new species of monopoly emerged. Success in a genuinely free and open capitalist system turned out to be hard work. Free-market capitalism was chaotic and unpredictable, its competition less free and fair than rapacious and destructive. Economic booms were followed by busts, fortunes made one day vaporized the next. The major players in this volatile economy—the railroads, steel manufacturers, financiers—sought more than mere profit. They wanted security. To be secure, they needed more control over markets than they had hitherto achieved.

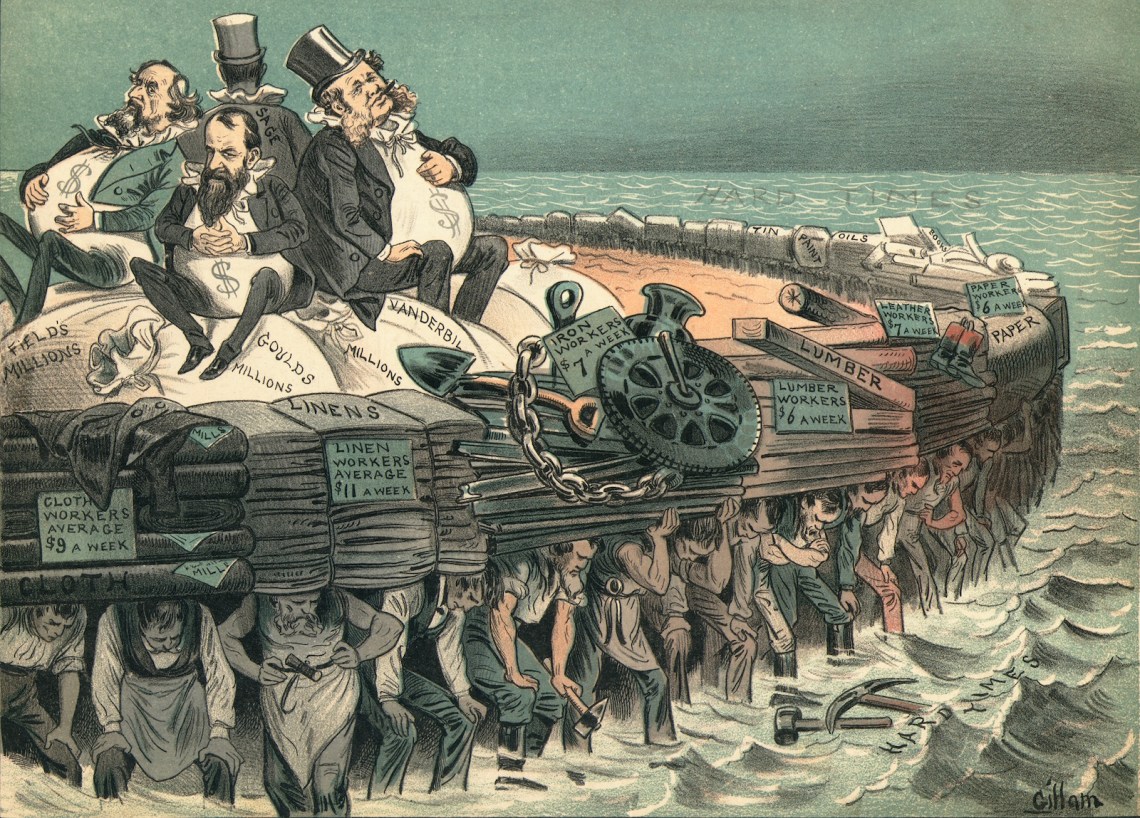

For the new men of power, dominating markets meant driving competitors out of business, or merging with them to create mega-sized firms. Increasingly, a few giant corporations ruled steel production, petroleum refining, sugar and meat processing, and chemical and electrical manufacture. These colossal entities became known as “monopolies” and sometimes as “trusts.” With that singular degree of control, these corporations imposed tough conditions on their workers and dictated the prices at which they would sell their goods. They corrupted politics, bribing officials to do their bidding.

By the 1880s and 1890s, these trusts were arousing as much ire among Americans as had George III’s abuses of power in the 1760s and 1770s. Anti-monopolist movements calling themselves Greenbackers, Grangers, Populists, Socialists, and the Knights of Labor sprang up in rural and urban areas and in the ranks of both native-born farmers and immigrant workers. All wanted to cut the economic monopolists down to size. They drew heavily on the slogans of the American Revolution, framing the economic despotism of their own time as a reincarnation of the tyranny of the British Crown. They provided the impetus for the Progressive movement of the early twentieth century, and deeply influenced the thinking of two presidents in those decades, Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson, who both believed that the economic power of monopolies threatened the future of the American Republic.

Advertisement

What was to be done with monopolies? One strategy was to break them up. A second was to regulate and, in extreme cases, nationalize them. A third was to impose punitive taxes on the companies, their owners, and their shareholders in order to reduce their wealth and clout. The Wilson-Gorman Act of 1894 was the first effort by Congress during peacetime to impose a punitive tax on the wealthy. It was modest in its ambitions, levying a tax of 2 percent both on corporate revenues and on personal incomes in excess of $4,000 (about $130,000 in today’s dollars). A clause in the Constitution (Article I, Section 2) mandating that any direct tax had to be fairly apportioned among the states led the Supreme Court to declare Wilson-Gorman illegal in 1895. But discontent at monopolies and at ill-gotten wealth continued to mount, impelling Congress and the states to pass and ratify in 1913 the enormously consequential Sixteenth Amendment.

This amendment gave Congress the authority to levy whatever sort of income tax it deemed necessary. The legislative branch then used this authority to inaugurate an era of taxation on the wealthy that today would be regarded as nothing less than socialist expropriation. In 1917, Congress imposed a tax of 67 percent on incomes of over $1.5 million, about $30 million in 2022 dollars (by way of comparison, the tax proposed by Senator Bernie Sanders would kick in at 1 percent on wealth in excess of $32 million, rising to a maximum of 8 percent on the wealth of the top multibillionaires). The tax rate on the wealthiest rose to 77 percent in 1918, fell back to 25 percent during the Republican administrations of the 1920s, and then, in the 1930s, rocketed to 75 percent on incomes over $5 million (about $100 million in 2022 dollars). A steeply progressive income tax had by then become one of the pillars of Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal; it was known—both hailed and pilloried—as the New Deal’s “soak-the-rich” scheme.

Roosevelt’s words matched his deeds. Dissolving the power of the rich had become a patriotic duty, he declared in his renomination speech to party delegates at the 1936 Democratic Party Convention. “In 1776, we sought freedom from the tyranny of political autocracy,” Roosevelt intoned, but in his time, the gravest threat to the nation lay with the “economic royalists” who “had concentrated into their own hands an almost complete control over other people’s property, other people’s money, other people’s labor.” Too many Americans now experienced life as “no longer free,” liberty as “no longer real.” Thus, Roosevelt concluded, “the average man once more confronts the problem that faced the Minute Man”: he must battle the economic royalists, “take away their power,” and thereby “save a great and precious form of government.”

Roosevelt’s attacks on America’s rich brought him one of the most resounding victories in the history of American politics. In 1936, he received more than 60 percent of the popular vote and 98.5 percent of the electoral college vote, carrying forty-six of the forty-eight states (only Vermont and Maine went Republican). Roosevelt’s New Deal had received an emphatic endorsement. Significantly, its income tax measures did not touch the masses of ordinary working Americans. Like those of the Progressive era, they fell exclusively on the wealthy, who comprised between 4 to 8 percent of the population. These measures thrilled large majorities of voting Americans while outraging the rich, who castigated Roosevelt, himself of genteel origins, as a traitor to his class. Roosevelt retorted that he was saving capitalism, not destroying it.

What would become of the new revenue flowing into government coffers? One obvious answer was the enhancement of the public good through the financing of infrastructural improvements: roads, bridges, airports, dams, canals, electrification grids, schools, post offices, and libraries. Another was to repair the damages of America’s industrial system through payouts to those injured on the job and to provide at least short-term economic relief to those who lost jobs to mechanization, market collapse, and capital flight. A third answer was to ameliorate the circumstances of vulnerable citizens—single mothers, the elderly, and the disabled—who simply needed a helping hand.

The 1930s thus saw the birth of America’s welfare state, a collection of government programs established to cushion the masses against the vicissitudes of a modern capitalist economy and, indeed, of life itself. It was the American version of social democracy. And a good portion of it had been made possible by the New Deal’s highly progressive income tax regime.

*

It was only a matter of time, of course, before this income tax–nourished welfare state ran afoul of the other tradition of taxation in America—the one that treated federal taxes as a suspect, even illegitimate, activity, the true manifestation of tyranny. Even before the New Deal fully took shape, these two dueling philosophies had begun to mold partisan politics. The Democrats were becoming the party of big government, extensive taxation, and wealth redistribution. The Republicans were casting themselves as the opposite: the party of small government, tax resistance, and private enterprise untrammeled by state regulation. The election of 1932 started these traditions on a path of collision when Roosevelt defeated Herbert Hoover, who, with his preferred heir, Senator Robert Taft of Ohio, were the standard-bearers for the Republican alternative. But that collision, which America had seemed to be hurtling toward in the 1930s, was delayed for forty years, first by World War II and then by a seemingly endless cold war.

All but the most ardent critics of statism and taxation in America muted their criticism in times of war emergency, with the understanding that opposition to a strong state would resume once wartime danger to America had ceased. The Union built a huge military and government regulatory apparatus during the Civil War, and World War I occasioned an even larger mobilization. After both conflicts, the armies raised were shrunk to a fraction of their wartime size, while the government entities authorized to maximize production for the war effort were dismantled. The aftermath of World War II presented a more difficult challenge.

The number of men under arms at the height of World War II was more than triple the equivalent peaks achieved in the Civil War and World War I. To pay for this colossal effort, Congress turned its “class” taxation system into a “mass” taxation system. During World War II, the fraction of Americans compelled to pay income tax vastly expanded—from about 5 to 67 percent of the working population. But the system did keep its steeply progressive character, with the marginal tax rate on the wealthiest Americans rising to an all-time high of 94 percent.

Between 1946 and 1948, it looked as though this war-and-tax regime would be revised much as its predecessors had been. Republicans were winning seats in Congress at a rate not seen since the 1920s. Large parts of the World War II military were being demobilized, and the tax rates and the proportion of Americans obliged to pay a federal income tax both fell. Then something extraordinary happened: the Republican Party sidelined its small-government, anti-tax partisans and accepted the big-government, high-tax regime installed by Roosevelt and his New Dealers.

The catalyst was the heating up of the cold war in 1948 and 1949, which drove Congress to put the nation on an emergency wartime footing yet again. The Soviet Union, it was feared, might attack at any moment, and the United States needed a central state with the power and resources to confront it. This was the moment when the Republican Party marginalized Taft and his small-government, anti-tax supporters, embracing instead Dwight D. Eisenhower as their party leader. Elected in 1952, Eisenhower proceeded to secure his party’s acquiescence to the big-government principles of Roosevelt’s New Deal order. In 1954, he presided over a comprehensive piece of legislation meant to render America’s high-tax regime permanent. It restored the tax on the highest income bracket to a level (91 percent) near its World War II peak. Eisenhower understood that high taxes constituted a burden. But, he asserted (in language that would shock twenty-first century Republicans), it was a burden that “every real American is proud to carry.”

Thus did the 1950s and 1960s become the apogee of federal power and taxation in America. The central government was flush, far richer than the states for the first time in the country’s history. Programs of public works flourished, manifest in road building, science and technology projects, and support for education at all levels. America’s welfare state, across the years of President Lyndon B. Johnson’s Great Society, reached its twentieth-century zenith, while the gap between rich and poor fell to its lowest point. Moreover, the Supreme Court, emboldened by the federal government’s success in the economic arena and the power it could now exercise over the states, chose this moment to respond to racial injustice by dismantling the Jim Crow system. The bipartisan consensus that cemented all of this held for as long as it did largely because of the cold war—until bitter divisions occasioned by the Vietnam War blew it apart.

*

Beginning in the 1970s, the sun that had shone so brightly on the New Deal’s high-tax, pro-government order began to set. A new political order took shape, one that sought to recover what its proponents saw as America’s true “revolutionary” origins: a government small in size and power, bereft of tax revenues, and privileging private power, individual freedom, and corporate autonomy. The fall of the Soviet Union, the death of Communism, and the end of the cold war delivered the final blows to America’s pro-government, high-tax regime. It was not a Republican president but Bill Clinton, who, in 1996, delivered the news that the “era of big government is over.” So it was that a Democrat legitimated the ascendant neoliberal order, much as the Republican Eisenhower had secured the triumph of the left- leaning New Deal order in the 1950s.

But this new order’s claim to represent “true Americanism” is no stronger than the equivalent claim once made by the New Dealers. The United States has never had one tradition of taxation, nor one attitude toward what a central state can and cannot do. It has always had two, and it is the conflict between them that defines American history, not the existence of one or the other.

The tradition eclipsed by the rise of the neoliberal order has now reemerged. The anti-monopoly animus revived as a political force in the aftermath of the Great Recession of 2008–2009, initially in Elizabeth Warren’s 2012 senatorial campaign and Bernie Sanders’s run for president in 2016. The movement has continued to gain strength since that time. Social media, digital technology, and e-commerce corporations are now drawing the kind of ire that late nineteenth-century critics of capitalism had directed at the dominant corporations of their day. President Joe Biden has appointed anti-trust insurgents from the Sanders-Warren camp—like Heather Boushey at the Council for Economic Advisors and Lena Khan at the Federal Trade Commission—to major posts in his administration.

Even such a figure from the moderate mainstream of the Democratic Party as Senator Amy Klobuchar has become a crusading anti-monopolist, her adoption of the cause amply revealed in the fighting title of her 2021 book, Antitrust: Taking on Monopoly from the Gilded Age to the Digital Age. Anti-monopoly sentiment has even spread from the left and center of the Democratic Party to the right of the Republican Party, where Missouri Senator Josh Hawley has opened another front in the war on what he likes to call “the tyranny of big tech.”

Hawley’s embrace of anti-monopoly arguments reveals both the promise and vulnerabilities of the movement. Its potential base of support is broad, extending from the social-democratic left to the Trumpian right, encompassing farmers and laborers, rural and urban dwellers, small business owners and blue-collar workers alike. This breadth of appeal helps us to understand how the anti-monopoly creed became, in its first heyday from the 1910s through the 1930s, an unstoppable force in American politics. Yet its very breadth is also its weakness: it is not clear whether the multicultural progressives of the left will ever be able to make common cause with the ethnonationalists who fill the ranks of Hawley’s would-be populism.

Still, the revival of anti-monopoly efforts simultaneously on left and right does suggest that we are living through a sea change in American politics. The days of the GOP’s pro-corporation, small-government, anti-tax disposition may be numbered, while the proposal to tax the super wealthy—until recently a demand of the Sanders-style, democratic socialist fringe—is getting the kind of hearing from the Biden administration that it never would have received during the presidencies of his predecessors Bill Clinton and Barack Obama.

In light of these developments, greater acknowledgment of the deep roots of America’s anti-monopoly tradition seems overdue. Its adherents have long declared that extreme concentrations of economic power in private hands are not tolerable in the American Republic. For three quarters of the twentieth century, this tradition gave government the legitimacy it needed to act as a countervailing force against the interests of the ultrarich and to use taxation as an instrument for redistributing wealth from the apex of American society to its middling and lower rungs. The United States once imposed very high taxes on incomes it judged so excessively high as to be antithetical to a republic consecrated to liberty. It can do so again.