Nadine Hwang led a dauntless life. What she did over the course of the twentieth century makes her sound like a superheroic projection from the twenty-first: a queer, Chinese fighter pilot and lawyer with a sword-dancing act who spoke at least four languages and survived a concentration camp, then ran away to Venezuela with the lover she met there, an operatic soprano.

She could have written a wonderful memoir, with a range of characters and incidents to rival that of her rough contemporary Arthur Koestler. But it seems that at every stage she was more interested in living her life than in putting it on paper. The records of her that do survive are scattered across three continents. At different times and in different countries her family name has appeared as Huang, Hwang, Wang, Huong, or even Juan. She seems not to have cared, but when she was rescued from the camp she signed it “Hwang.” (I first came across her name, spelled “Wong,” reading about the American expatriate writer Natalie Clifford Barney, her former lover.) She pops up obliquely, through the eyes of others: a journalist in Portugal, a novelist in Paris, the memoirs of her sister, a camera in Sweden. Such accounts are often difficult to substantiate.

Hwang and her partner, the singer Nelly Mousset-Vos, are the subject of a new documentary, Nelly and Nadine, by Magnus Gertten, a filmmaker who first came across Hwang while investigating the Red Cross’s partial evacuation, just before the war’s end, of the women’s concentration camp of Ravensbrück in northern Germany. Unfortunately, the film pieces together little of Hwang’s life before her internment, apart from her involvement in glamorous Parisian lesbian social circles. Gertten’s investigative spadework, however, gives those who care about her life one tremendous new gift: by tracking down Sylvie Bianchi, the surviving granddaughter of Mousset-Vos, he fills in a good deal of the missing information regarding what happened to Nadine in the years between the end of World War II and her death in Brussels in 1972. The documentary reveals that after half a century of adventures and hardships, Hwang’s life culminated in something like happiness.

*

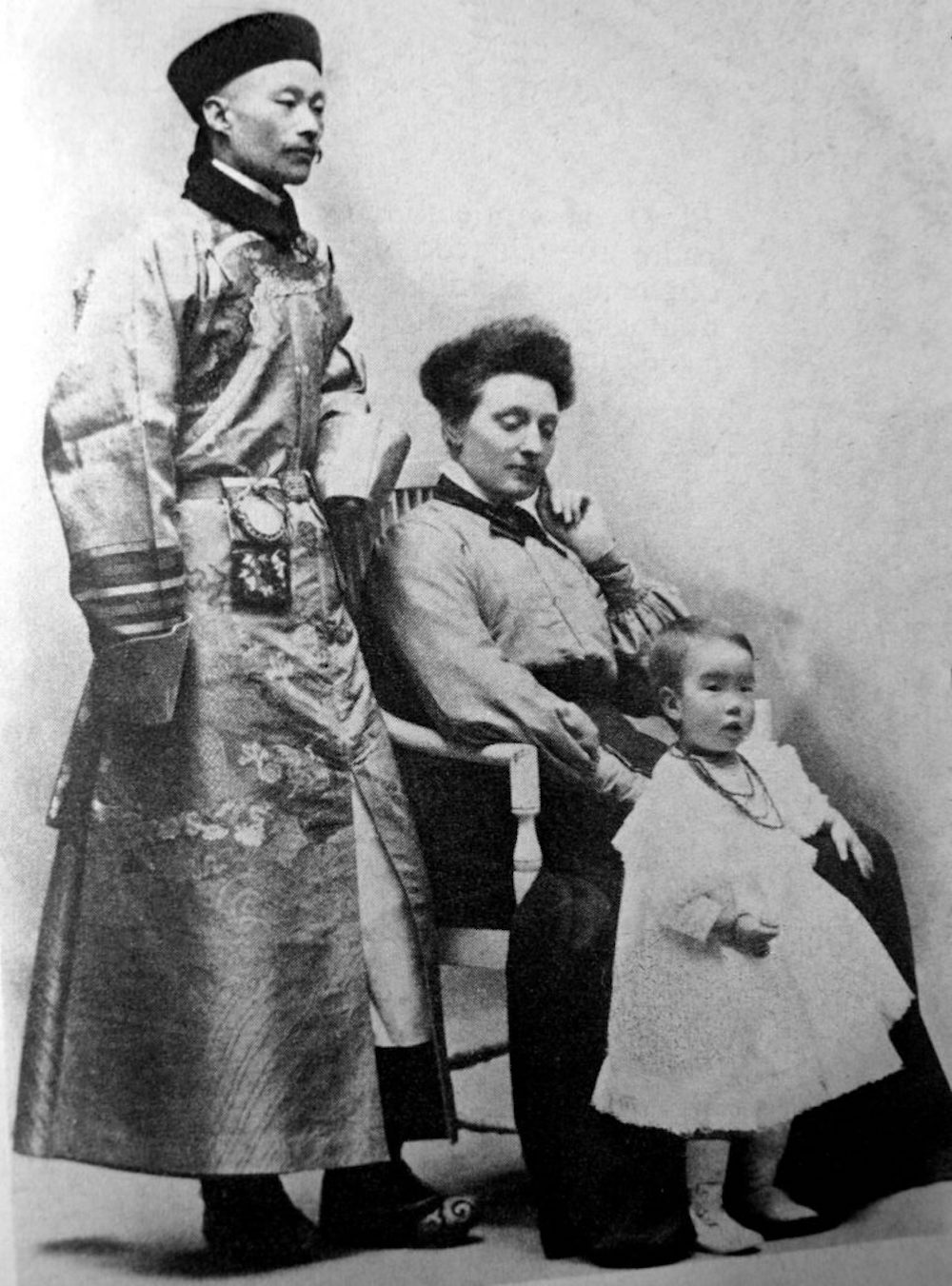

Hwang was born in Spain in 1902 and spent her early years there and in Cuba. Her father, whose name would now be romanized as Huang Lühe (黄履和), served as a diplomat for the Qing Dynasty in its waning years, following China’s defeat in its first war with modern Japan. A Spanish paper later described him as “simpático, afable, sonriente.” Lühe married a young Belgian widow named Juliette Broutá-Gilliard. (Their engagement was negotiated through an interpreter.) Nadine, whose Chinese name was Na-ting (黄訥亭), was their first child. A photo shows Lühe, in the robes and cap of a minister and wearing the queue, towering above Julietta as she sits in a conservative white blouse; she stares down at Hwang, a toddler in a fluffy frock and several necklaces, gaze already intense. The family was posted briefly to Havana, where Nadine’s sister Huang Ma-ce (黃瑪賽), two years her junior, was born; they then returned to Madrid. (Ma-ce later hispanized her name to Marcela de Juan, under which she became one of the century’s most important translators of literature from Chinese to Spanish. Her memoirs have recently been published under the title La China que viví y entreví.)

Hwang’s father kept his position through the 1911 Revolution, which ended the Qing Empire, and the family returned to China in 1913, following the child emperor Puyi’s abdication. The children grew up educated in English and speaking Spanish, French, and Chinese; in Beijing, they continued their educations at a Catholic school. Hwang later told a Portuguese paper that she shocked her Chinese family with her “Spanish habits.” When a great-uncle reminded her that someday she would owe a husband her total obedience, she shot back, “Except when he tells me to do anything legitimately stupid.”

Even amid the chaos of the Republican period, their father’s position offered the sisters access to high society. They were said to be fixtures in Beijing’s finest hotels, dancing in the European style. Hwang cut a dashing figure, already fond of sharp suits and crisp, short haircuts. Marcela later remembered that the young Mao, at twenty-three, once came to see her father with a complaint in 1918; Lühe told the girls, “Get a good look at that man—remember him. He might have a great future ahead.” Other sources claim the Huang family crossed paths with the writers Hu Shi and Lin Yutang.

Hwang told Spanish journalists in 1929 that when she was nineteen, a general then spearheading the nascent Chinese air force (she later identified him to French journalists as the Shandong warlord Zhang Zongchang) saw her dressed as a young Spanish baturro for a costume ball and asked her why she was wearing trousers. She answered that it was the only way you could ride a horse, swim, row, or box. Impressed, he sent her to a military academy and then made her an “honorary” colonel. (Hwang chafed at the honorary part.) Zhang’s later reputation for particular truculence among the strongmen then vying for power makes Hwang look all the more formidable. Her title became an important part of the press’s fascination with her when she returned to Europe in the 1920s: “A Chinese Joan of Arc” and “A señorita from Madrid becomes a colonel in the Chinese Army,” read headlines at the time.

Advertisement

At some point during the early 1920s she became a lawyer by mail through correspondence courses with a now-defunct law school in Chicago. Together with her language skills and family connections, she parlayed this credential into an ever more singular set of opportunities. Successive Chinese leaders dispatched her as part of diplomatic missions—the earliest in 1925, during which she spent several days learning to fly planes at Le Bourget airfield outside Paris. On returning to China, she insisted to Zhang that she be made an active pilot, though to her dismay she never saw combat. In 1926 she was part of a delegation to the United Kingdom; the next year, during the short-lived government of Zhang Zuolin, Prime Minister Pan Fu made her press secretary to the Chinese economic mission to the United States, where she traveled to Albany and Oregon.

Chiang Kai-shek seized control of the Chinese government in 1928 while Hwang was still abroad, but she seems to have been good at keeping up powerful friendships. In 1930 she met a young Isamu Noguchi as he passed through Beijing; in his autobiography he called her a “beautiful lieutenant in the army of the young marshal Chang Hsueh-liang (who wanted me to become a general).” The Japanese invasion of Manchuria in 1931 raised the stakes of her work dramatically. She had to keep imploring European journalists to talk less about her clothes or her image as the “Amazon of the North” and more about China’s struggles against the Japanese Empire’s encroachment.

*

By 1933 Hwang had relocated more or less permanently to Paris, and while she continued to work on behalf of the Chinese government, leading a trade mission to the UK in 1936, a second chapter of her life had begun. She entered the orbit of Natalie Clifford Barney, whose salon was a renowned meeting place for artists and thinkers—especially queer women. (A brief scene in Gertten’s documentary is given to the late biographer Joan Schenkar, explaining Barney’s world and Hwang’s place in it.) Following the model of her past lover and mentor Renée Vivien, Barney aspired to recreate the school of Sappho in modern Paris; she lived in a house with Greek columns to which she invited, over the years, Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas (the latter a lifelong friend), Colette, Djuna Barnes, and Mina Loy, among others. Hwang was, for a time, in charge of organizing the salon’s amateur plays.

Starting around 1935 Hwang was part of Barney’s fluid inner circle of lovers. Barney also hired her as her driver, which may have served partly as cover for the relationship. Hwang called Barney her “darlingest own” and grew possessive of the older woman, though Barney later referred to their relationship as “a fling.” Hwang competed for Barney’s affections with Dorothy Wilde (niece of Oscar), who called her rival “that horrible Chinese”; for her part Hwang told Barney that Wilde, a heroin addict, was smuggling opium out of Fontainebleau. The relationship had cooled by later in the decade; Barney was dealing both with Wilde’s addiction struggles and with her own long-running relationship with the painter Romaine Brooks.

Brief essays on Hwang have claimed that she met the full cast of characters one expects in interwar Paris—Picasso, T.S. Eliot, Stein—and while there is no proof, there is some evidence that she was everywhere and knew everyone. The British novelist Radclyffe Hall, whose obscenity trial for her 1928 novel The Well of Loneliness had become a cause célèbre for queer writers of the day, warned her lover Evguenia Souline that Hwang was a notorious gossip: “Please be jolly cautious about what you say to her or before her. She is the person above all others who simply must not suspect our relationship. Via her and Natalie it would be all over Paris.” (Hwang and Souline played ping-pong together.)

Advertisement

As Europe descended into war, Hwang’s activities grow murkier. By the time of the Vichy régime, as later correspondence attests, she was helping people flee the Nazis across the French border into Spain. Various unsourced biographical sketches suggest that her skill at passing for a man allowed her to pose as a German soldier while spying for the Resistance. She nearly made it through the war unscathed, but in May 1944 her luck ran out, and for uncertain reasons—possibly either her nationality or sexuality—she was sent to Ravensbrück.

*

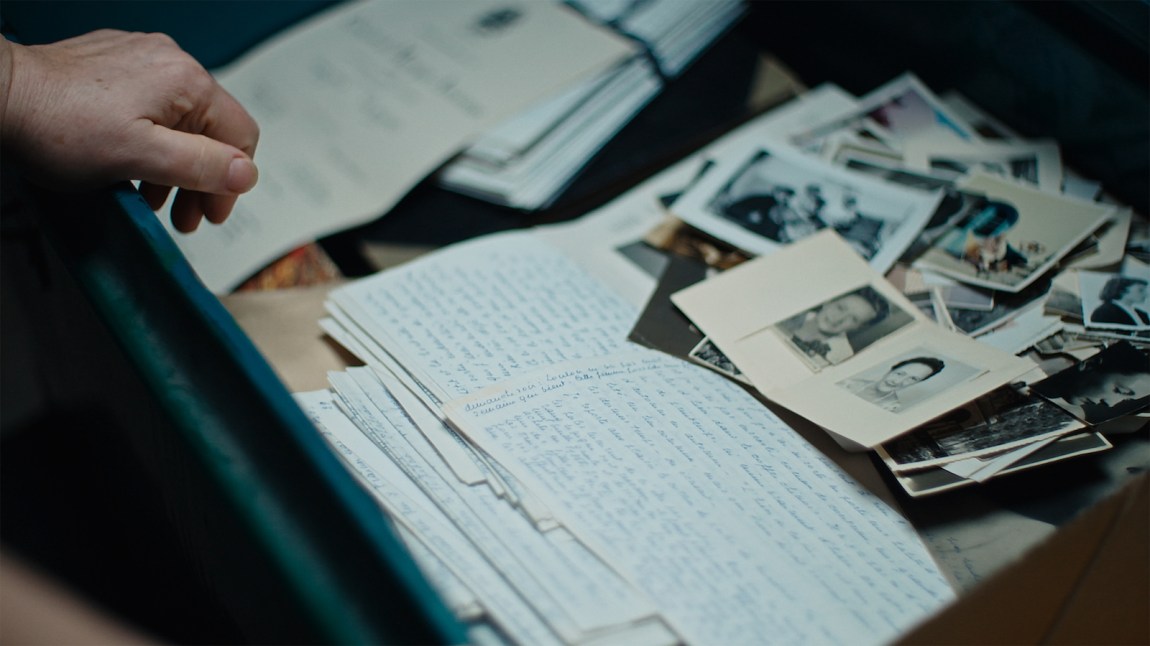

Nelly and Nadine largely omits these details of Hwang’s life, apart from her time in Barney’s Paris circle—but Gertten can almost be forgiven on account of his film’s graceful, dignifying reconstruction of her love for Mousset-Vos. Sylvie Bianchi inherited her grandmother’s papers from her mother, who had a tense relationship with Mousset-Vos and seems to have disliked Nadine intensely. For years, Bianchi found looking at the archive overwhelming. Gertten’s inquiry prompted her to finally open them. Together with photographs, letters, and a number of home movies Hwang shot of Mousset-Vos, she found a book-length account of their time in Ravensbrück, compiled from Mousset-Vos’s diaries and apparently edited by Hwang, who also copied it out by hand.

Their meeting itself was operatic. Mousset-Vos had been arrested in 1943 as an agent of the Belgian Armée secrète. (Her name, too, was fluid. In some sources it appears as “Nelly Voss,” in others “Nelly Mousset.” Nadine called her “Claire.”) The prisoners of Ravensbrück were permitted a concert on Christmas, where Mousset-Vos, who had once sung demanding roles in Darius Milhaud’s Les Euménides and other works, was asked to perform.

In her telling, snow was falling. After several French carols, a voice suddenly rang out in the crowd, “Sing something from [Madame] Butterfly!” So she sang that opera’s famous aria “Un bel dì vedremo.” (In recordings, her soprano is throaty and commanding; Bianchi remembers it “was like a volcano.”) As she sang, “Joy overpower[ed] me—a dionysiac joy.” After the applause died down, a woman ran up from the audience: “Two arms grip me, two kisses on my cheek. Butterfly is right in front of me. Her black hair, her ivory skin, her oblique eyes. Nadine.” Later in January, as they fell asleep holding each other, Hwang spun imaginary feasts of caviar and champagne.

In February, Mousset-Vos was transferred by cattle car to Mauthausen in Austria, nearly dying of hunger and abuse; Hwang remained behind. Both were rescued by different chapters of the Red Cross in April 1945. Hwang was taken with others to Sweden, where she was quarantined with Mary Lindell, a captured British spy; they fell out when Lindell hurled a racial slur at Hwang. The Republic of China’s legation was aware of Hwang’s presence in Sweden and helped her move within the country, but rather than return to China she traveled to Belgium to try to locate Mousset-Vos.

After reuniting, they moved to Venezuela in 1950, hoping to shake off the memories of the war years, according to a friend from that time. Life in Caracas was quiet. Mousset-Vos worked for the French embassy; Hwang found a job with a bank, where, as ever, her languages were an asset. Always an enthusiast for technology, she enjoyed shooting home movies, particularly of Mousset-Vos. A console in their home displayed porcelain and photos of the two when they were young. A large lacquered chest served as a nightstand; the apartment was filled with paintings. Nelly, hair pulled back into a bun, was fond of pearls; Nadine chain-smoked. They held soirées with friends, including other queer couples, male and female. Photos show them in full evening dress, cocktail glasses in hand, looking like they wandered in out of a scene from Proust. They had a dog. Nelly’s granddaughters came to visit. “Your grandmother is a war hero,” Nadine reminded them, without entering into details.

In 1969 the couple returned to Belgium, where Mousset-Vos was still a citizen. Hwang passed away in February 1972 without fanfare, but Mousset-Vos’s sense of loss carried the weight of the world. “Is it my fault if every move I make, every thing I touch, evokes your hands, your body?” she wrote in her diary prior to her own death in 1987. “No one to notice my new dress, no one to help zip it up. I wait for you, as if you were on a trip.” To the very end, it was through the words of others that Hwang appeared, refracted.

*

Hwang’s story has drawn little sustained attention through the years. There are so few sources on which to build a proper biography, and chasing down all the surviving fragments would require years of travel to archives around the world with no guarantee that the pieces would coalesce. A novelist might write a brilliant evocation of her life, except that what she did so often seems implausible.

On one hand, Hwang’s life gratifies the contemporary longing for recovery of stories of marginalized groups. On the other hand, she is almost too exceptional to be a good historical representative of anyone other than herself. Her life was shaped by strong, mysterious displays of will. Why fly planes? Why stay in France, where it would have been nearly impossible to blend in, doing dangerous work she could have left? She was caught up in history but refused to accept the conclusions toward which it ushered so many others. Privileges helped: few other women with her aspirations, especially from early twentieth-century China, had the social background, educational preparation, or linguistic range to seize the opportunities she did. But few, if any, lived a life quite like Hwang’s, even from her own class. (Her sister’s life, for instance, while rich with accomplishments, was more tranquil.) In a sense, Hwang achieved what Nietzsche and Foucault once idealized: rather than making art, her life itself became a work of beauty, pathos, and inspiration.

Bianchi says her grandmother’s manuscript was meant to share her and Hwang’s love story with the world: how they met, how they fell in love in a place dedicated to death, and how they found each other again. They tried to find a publisher, but in those days no one would take it. The most aggravating experience of Gertten’s film is encountering so many scraps of what Mousset-Vos wrote—clearly in beautiful detail—and Hwang helped arrange, yet not being able to read the whole. Someone ought to publish it.