In the mid-twentieth century the early Renaissance painter Piero della Francesca was reappraised by Anglophone artists and art historians who considered him a Modernist avant la lettre. In their eyes he had flouted convention at Western art’s pivotal moment, breaking with the naive rendering and garish coloring of medieval painting and using his knowledge of geometry to model rigorous pictorial spaces. Philip Guston suggested that Piero registered both painting’s “continuity” and its historical “frustration”—a position relevant to artists of Guston’s generation, concerned as they were with the medium’s ongoing viability. Bernard Berenson likewise read the present into Piero’s past, noting the artist’s deadpan affect, his “unemotional, unfeeling figures” bearing mute witness to their turbulent history. “In a moment of exasperated passions like ours today,” Berenson wrote in 1954, Piero’s work “calms and soothes.”

A few years later the young painter Bob Thompson perceived this affect differently. It was not an apotropaic balm, he argued, but rather a sign of Piero’s personal and artistic complexity. In these paintings, especially in their idiosyncratic use of color, Thompson saw “a man who felt the activity of his environment.” It was a canny analysis, and a revealing one, since Thompson would prove to be such a man himself. Arriving to the East Coast from Kentucky at the start of the 1960s, he fell in with several intersecting groups of artists: the mostly white painters, like Larry Rivers and Alex Katz, who heralded the end of Abstract Expressionism and returned in diverse ways to figuration; the mostly Black jazz musicians, like Ornette Coleman and Archie Shepp, forging past bebop; and the Beat and post-Beat writers, like Allen Ginsberg and Amiri Baraka (then LeRoi Jones), soon to activate divergent cultural revolutions. He was attuned to art’s traditions even as he planted himself among practitioners self-consciously devoted to its forward movement.

Thompson’s comments about Piero appear in a paper he wrote as an undergraduate at the University of Louisville. The typewritten manuscript sits in a vitrine alongside other archival materials at the Michael Rosenfeld Gallery in Agony & Ecstasy, one of two Thompson exhibitions currently on view in New York. The other, So let us all be citizens, curated by Ebony L. Haynes, is at 52 Walker. The exhibitions together present around thirty Thompson paintings, plus, at Rosenfeld, some works on paper, all produced between 1958—when he left Louisville for stints in Provincetown, New York, and Europe—and 1966, when he died at twenty-eight.

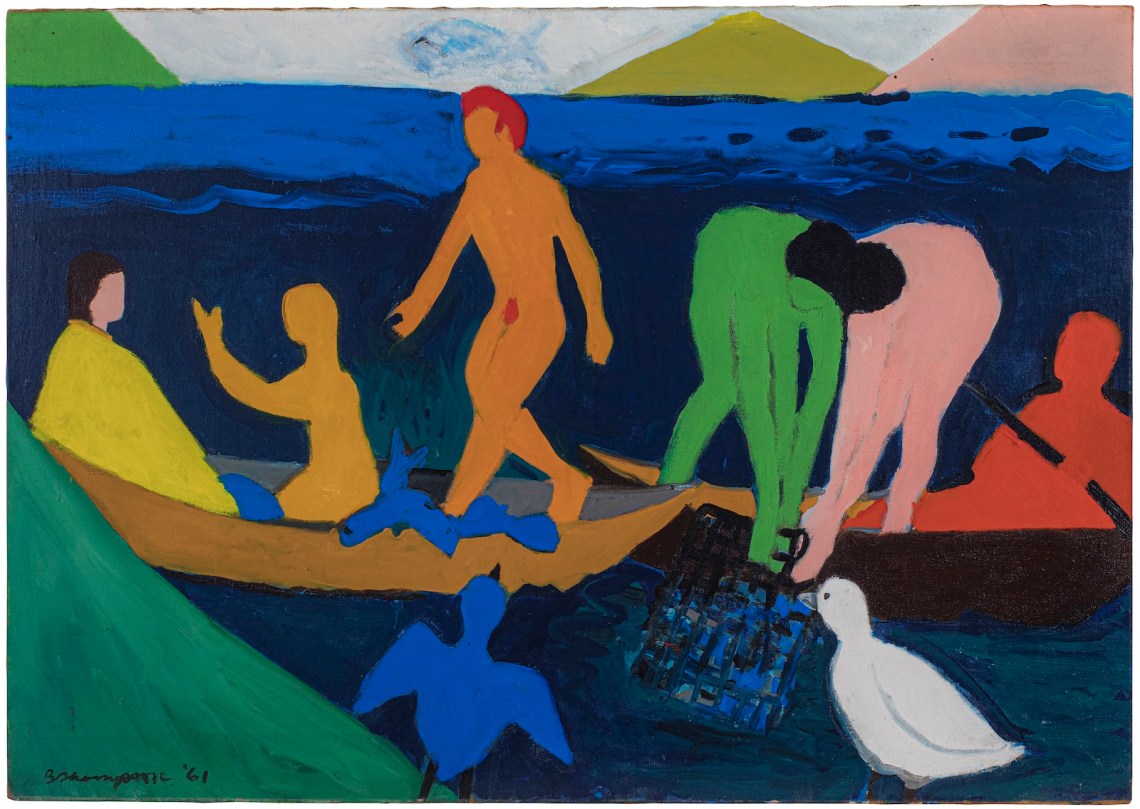

Many of these paintings make loose pictorial references to the old masters—Raphael, Poussin, Goya—and sometimes to multiple sources at once. (Baraka wrote that Thompson had “Giotto-maniacal recall.”) Two at Rosenfeld cite Piero: Nativity (1961) and Untitled (The Proofing of the Cross) (1963). They press the “unemotional” quality of Piero’s figures by effacing their features altogether, a common trait of Thompson’s work. In the earlier painting, the arrangement of the central figures follows that of Piero’s Brera Madonna (1472), but the story has shifted from sacra conversazione to nativity scene, and the setting from church to pastoral landscape, in a possible reference to a different Piero picture, The Baptism of Christ (1440–50).

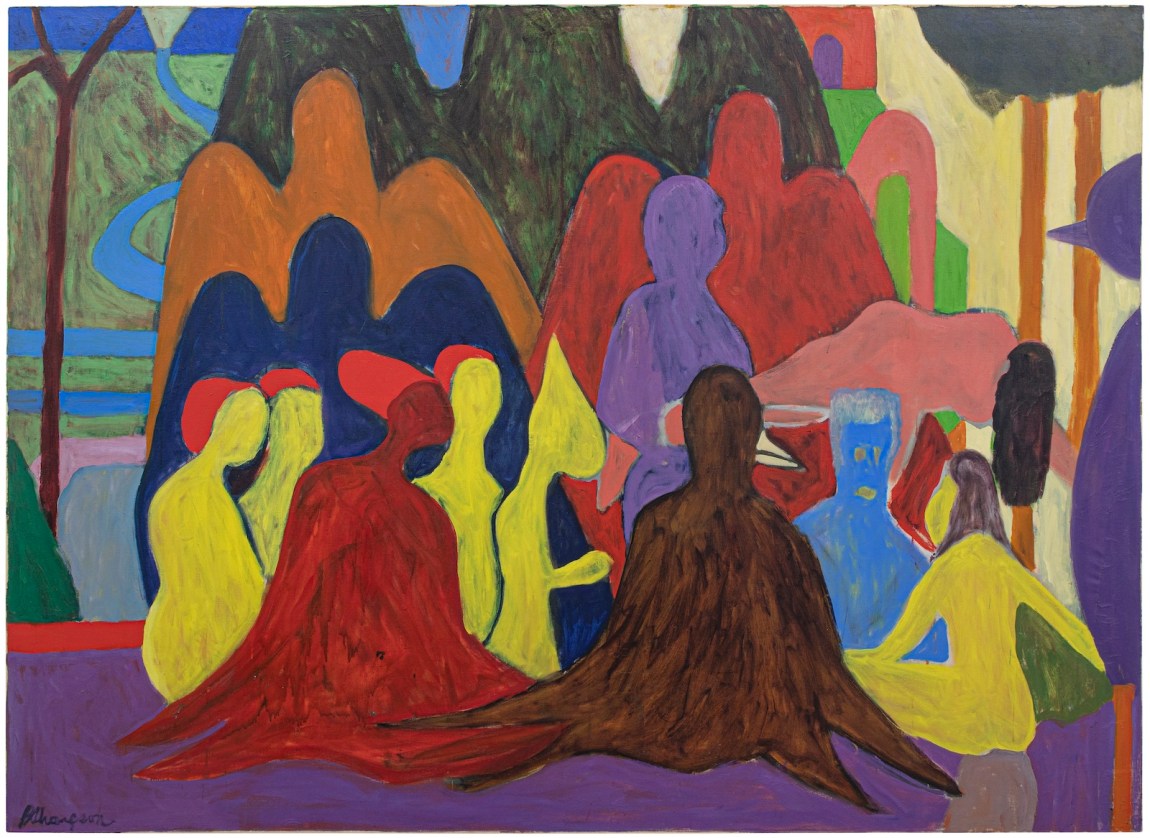

The Proofing of the Cross is more distinct from its referent, a vignette from the Arezzo frescoes. Seated as if performing a ritual, the figures in Thompson’s version appear as distended, even monstrous, silhouettes of yellow, blue, and purple, rendered in flat, motile brushstrokes. In his paper Thompson had written that Piero deployed “color not in the general sense of flesh tones, but as a means of creating patterns.” Accordingly, he leaves only the shape of the original intact. Absent any modeling or narrative cues, Thompson’s scene, like the proof of the cross itself, buttresses an abstract resurrection. As the artist Frank Bowling understood, “What we thought was Piero disappears and we have a Thompson.”

*

Thompson was born to a middle-class Black family in Louisville in 1937 and raised in nearby Elizabethtown. He was a precocious artist and athlete, a devoted son and brother, and an aspiring pastor (the title of the Walker exhibition derives from an adolescent sermon). After graduating from Louisville’s all-Black Central High, he briefly attended Boston University before returning home, where he earned a scholarship to the Hite Art Institute. The Institute’s faculty included German émigrés like the artist Ulfert Wilke and the art historian Justus Bier, who exposed Thompson not only to old masters but also to Modernism—the Fauvists and Expressionists who helped ignite his work.

Around town he could also see abstraction on tour from New York and gestural figuration from California. Perhaps most impactful was Louisville’s Black arts scene. Inspired by the poet and artist Ted Joans, painters including Thompson and Sam Gilliam staged events that combined poetry readings, musical performances, and collective painting projects. Still, by 1959 Thompson had separated himself from the pack. In a statement for a solo show downtown—a rare feat for a young, Black artist—he asserted his independence, the importance of cultivating his own style: he needed to be “free to express that which is visually true to me.”

Advertisement

The earliest works in the Rosenfeld exhibition trace his path to freedom. In a pastel self-portrait (circa 1958–1959) executed with quick but precise marks, he stares sternly ahead, hands down. These faculties—eyes, hands—have sprung into action for the oil painting Black Monster (1959). He had spent the summer of 1958 in the artistic hotbed of Provincetown, where he studied at the Seong Moy School of Painting and Graphics, met Red Grooms and Emilio Cruz, and saw work by the recently deceased Jan Müller. Black Monster translates Müller’s patchy figuration and idyllic settings into Thompson’s burgeoning iconographic language. Three figures—two nude, light-skinned women and a black-hatted character being lifted onto a horse—contort their bodies as a fang-bearing creature lunges toward them. The landscape’s bright colors clash with the gray sky, as if to emphasize the scene’s unreality. “The Monsters,” wrote Thompson to one of his sisters, “are present now on my canvas as in my dreams.”

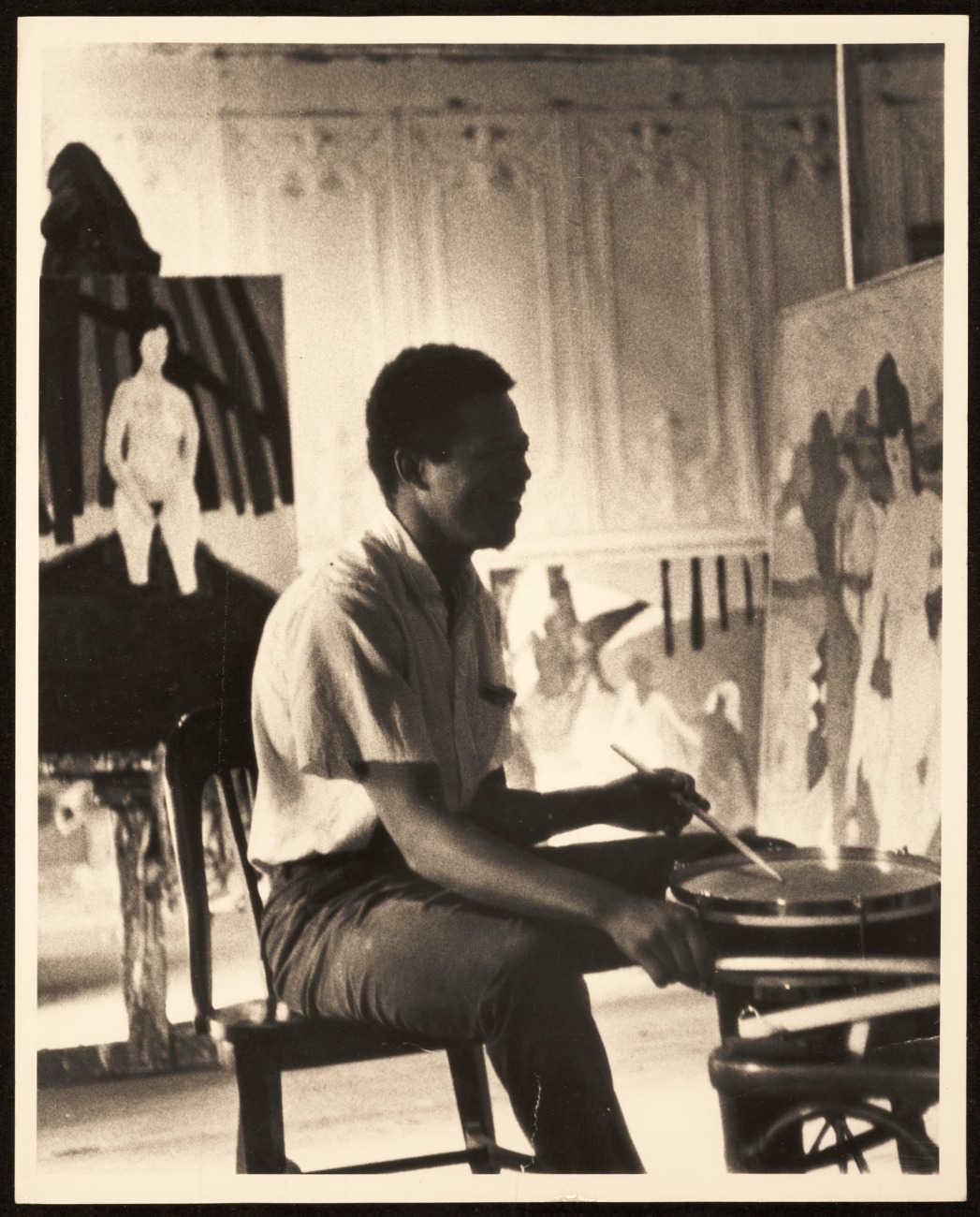

By the time Thompson finished Black Monster he was living in downtown New York, where he participated in Grooms and Allan Kaprow’s inaugural Happenings and described himself as an “esthetic junkie.” (He also struggled with drug addiction.) The young artist painted day and night, often before an audience of friends. Canvases like The Gambol (1960), at Walker, thematize this method’s contingency in both content and form: figures on horseback, painted in frenetic strokes, dissipate into the forested backdrop as they ride away. After his New York debut that year at Grooms’s Delancey Street Museum, where Meyer Schapiro bought a piece, Thompson showed at notable galleries in New York and Chicago, and garnered praise from Jill Johnston, Donald Judd, and Robert Pincus-Witten. The latter two tempered their approval with condescending words like “naiveté” and “inadvertence,” perhaps reserved for artists of Thompson’s age and race. Yet to others Thompson was advanced. Baraka called him a “fantastic emotionalist… much stronger than those rich whiteboys we hear so much about.”

In addition to their friendship, Baraka and Thompson shared a fraught position in New York’s art world. Alongside friends like Cruz and Joe Overstreet, they were fluent in Western modernism and friendly with some of its latter-day practitioners but also sought new, Black vernacular forms. One title at Walker, Wagadu (1960), invokes an African heritage, but the most pertinent source of newness for Baraka and Thompson was American jazz. Frequenting the Five Spot and Slugs’ Saloon, which displayed a painting of his, Thompson obsessed over bebop and, even more, the “new thing,” the free music of Coleman and John Coltrane. In 1963 Baraka wrote that artists like Coleman, feeling bebop’s exhaustion, had given jazz back its “valid separation from, and anarchic disregard of, Western popular forms.” This was not to imply that they negated everything that had come before. Rather, Baraka argued, elements of the past provided musicians with raw material for experimentation: Coleman “uses [Charlie] Parker only as a hypothesis.”

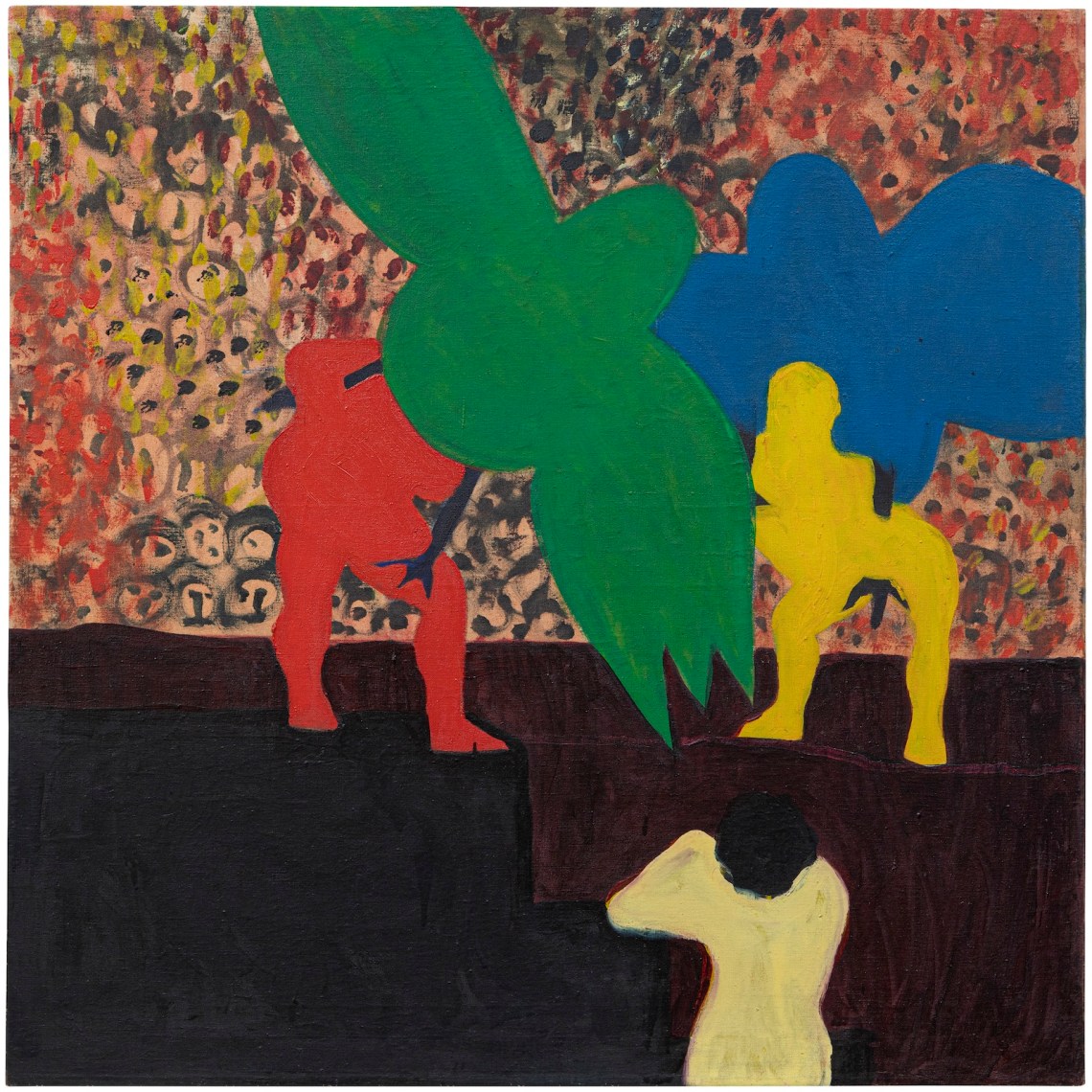

In this vein Thompson’s painting has often been compared to jazz, with his art historical quotations recast in musical terms like “improvisation” and “variation” (which Thompson himself used). He “varies” several prints from Goya’s series Los caprichos (1799) in pieces at Rosenfeld; one of them, The Circus (1963), replaces the private struggle of The Sleep of Reason with a public spectacle of bestial violence. Giant birds grasp at the groins of brightly colored human silhouettes while a wall of distended cartoon faces looks on—a possible allegory for Thompson’s simultaneous visibility and inscrutability among New York artists.

Some writers further emphasize Thompson’s biography, linking his many depictions of sex and sexual assault to the precarious social stakes of his 1960 marriage to Carol Plenda, a white woman—as if the pictures play with the fantasies of racists. Bacchanal (1960), at Walker, portrays dark figures entangled with lighter ones, the details of their entanglement left obscure. It might be seen in turn as one of his many paintings that, as the historian Crystal N. Feimster writes in the catalogue for a recent Thompson retrospective, “reimaged the racial and sexual landscape of Jim Crow America into a vision of interracial sexual freedom that blurred the lines between pleasure and violence, man and beast, good and evil.” The Execution (1961), loosely based on a work by Fra Angelico, could present an imagined coda to Bacchanal: the apparent lynching of a black figure who assumes the position of what is, in the original, a martyr.

Advertisement

The Renaissance and baroque scenes of sexual violence Thompson invokes often naturalize their tortured content, filtering it through familiar genres, pictorial idioms, and narratives. Thompson, in contrast, refracts it, matching and even heightening the uncertainty these scenes can provoke. In the process, he also draws a connection between the violence of his so-called early modern sources and that of straightforwardly “modern” art. In color and style, after all, paintings like The Gambol and Bacchanal recall the Renaissance less than they do the fin-de-siècle work of artists like Paul Gauguin—who extrapolated modernist techniques like ornamental patterns or nonperspectival space from their country’s colonial spoils and their own primitivist fantasies. “Modern art and imperialism are the eternal twins,” Cruz wrote in 1969. Thompson seemed to grasp this kinship, to poke it with his brush.

*

With the patronage of Walter Gutman, Thompson and Plenda went to Europe in 1961, staying mainly in Paris and Ibiza until 1963. Like other Black artists such as Romare Bearden, Ed Clark, and Robert Colescott, Thompson found inspiration and support abroad. In Paris he befriended expat artists and musicians like Jackie McLean, who admired his social verve and artistic productivity. (At Thompson’s studio, McLean recalled, he found canvases “rolled up like rugs.”) Barbara Rose often saw Thompson at the Louvre; like Cézanne, he sketched from the Poussins.

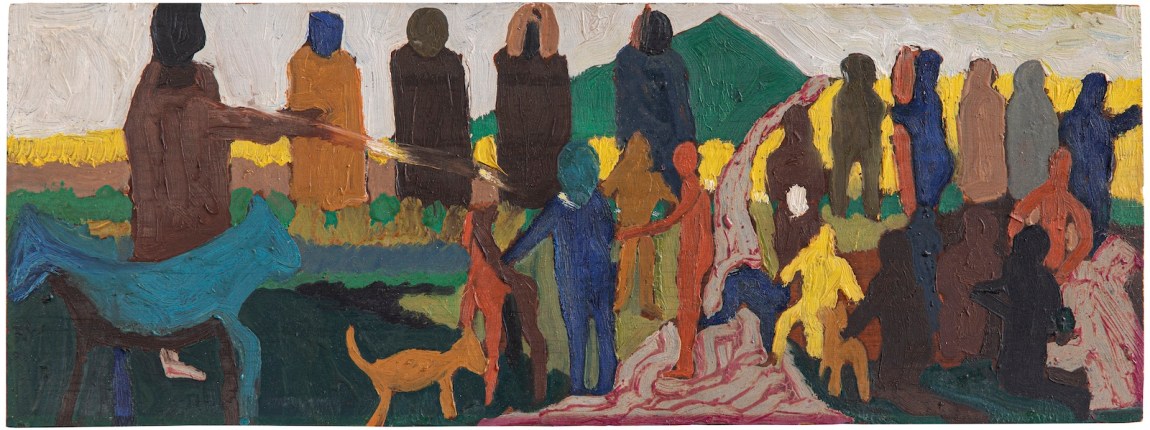

Triumph of Bacchus (1964), at Walker, adapts parts of paintings of the same theme by Poussin and Annibale Carracci. Thompson swaps the procession of mythical figures for warm-hued humans, birds, elephants, a giraffe. Poussin, he wrote in 1965, taught him relationality: “mass against movement.” Each of their Triumphs presents its parade as a mass of interconnected bodies, yet where Poussin’s movement derives from a single, sweeping curve, Thompson creates a more unpredictable, centrifugal motion. Figures lean on, grab at, or dissolve into one another; three birds try to escape at the edges of the group, drawing the viewer’s eye to a cavern of ordered trees at back left and an atmospheric sky across. Some critics have argued that the colors in Thompson’s paintings suggest a fantasy of racial integration, figures of variegated flesh tones joined in communion and even triumphal celebration. But it might be more appropriate to say that he models the coexistence of difference—even subtle difference, like shades of orange—as a dynamic process. The group moves, but not in any particular direction, and only with friction.

“I have interpreted this composition as I see it and feel it just as Poussin might have done with the same scene,” Thompson wrote, “the subject being the same, but the interpretation different.” Looking at Poussin, he discovered that “you can’t draw a new form”; all forms have “already been drawn.” Still, you can extend and personalize them, multiplying their meanings and their places in history. In the lingo of the art historian George Kubler, who enjoyed influence among New York artists of the mid-1960s, Thompson could have been tracing the diffuse “shape” of time—the simultaneity of old and new legible in art’s formal variations across history. Historical time, for Kubler, could not be described using linear scientific models. “It is more like a sea occupied by innumerable forms of a finite number of types.”

Reviewing Ornette Coleman’s record The Empty Foxhole in 1968, in the thick of the Black Arts Movement, Larry Neal emphasized individual agency more than Kubler. Black artists, he wrote, possess a distinct relationship to time: “We make or create time instead of keeping time like a metronome. ‘To keep’ time is a Western concept.” Thompson may have thought it was impossible to draw a new form, but he could make time, bending history to fit his experience. More than the dialectic of “frustration” and “continuity” that Guston saw in Piero and that Clement Greenberg gave a central place in his influential theory of modernist painting, Thompson’s art funnels different moments back and forth unevenly, unpredictably.

Thompson died of a lung hemorrhage soon after an operation in Rome, where he and Plenda had moved in 1965. Attesting to his broad social and artistic influence, there were two large memorial events in New York: a service with readings by Baraka and A. B. Spellman and a group exhibition featuring a who’s who of downtown artists, like Cruz, Grooms, Kaprow, Katz, Raymond Saunders, George Segal, and many more. Archie Shepp recorded “A Portrait of Robert Thompson (as a Young Man),” an eighteen-minute riot that concludes with an exuberant but tragic march—a tribute that rises to the complexity of its subject, in form and spirit.

*

The paintings currently on view make it clear that Thompson both emerged from and reacted to the social and artistic movements of his time. Named after the jazz standard, Stairway to the Stars (circa 1962), at Rosenfeld, is unique in his oeuvre not just for the dimensionality of its figures but also for its material ground: a photostat of an American Airlines plane. (Comparisons to contemporaries like Bearden or Rivers are more apt now than to Piero or Goya.) The figures—including friends of the artist like Ginsberg, Grooms, and the bassist Charlie Haden—descend the plane’s stairs into the sort of landscape that Baraka, writing about Thompson, called a “lollypop dream.” Bulbous trees scale the picture; vertical patches of impressionistic color flatten the space despite the photostat’s insistent depth.

One could miss the piece’s autographic mark at bottom center. Many of Thompson’s paintings portray this figure: Black, featureless beyond the intimation of a porkpie hat like the one Thompson (and, he might have noted, Lester Young) sometimes wore. Some critics imagine it to be a self-portrait. Here the figure, like Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man, observes but is not observed. He feels his environment up close and yet as if in a dream. “I am trying,” Thompson once said, “to show what’s happening, what’s going on…in my own private way.” This hatted figure reappears in several canvases displayed in New York, such as The Bathers (circa 1964–65), at Walker, which interprets scenes by Cézanne. Bodies of varied color, definition, and size press forward against the picture plane, their leisure strained. What’s going on? It’s hard to tell, but Thompson’s avatar stands at the left edge—pointing, trying to show us.