In March 2015 I visited a friend, the Argentinean journalist Sandra Crucianelli, and her husband, Gabriel, for dinner in Bahía Blanca, a coastal city about four hundred miles south of Buenos Aires. I had just moved to Argentina from Dubai, seeking to report on environmental issues. Bahía Blanca, known as the “great metropolis of the south,” is a port city and a principal entry point for the Patagonia and Pampas regions. On our way to dinner we drove past Art Nouveau façades in the city center, which was crowded with well-dressed tourists and students from the city’s national universities. Bahía Blanca’s residents enjoyed a high quality of life, with access to sprawling shopping malls, golf courses, a symphony, an opera house, and a ballet. The city is also strategically located, adjacent to Argentina’s largest naval base, Port Belgrano, and an air force base. On the horizon I traced the silhouettes of the Sierra de la Ventana mountains, popular for hiking. Politicians cited Bahía Blanca’s prosperity, a product of industrial policies implemented in the 1980s, as a model for the development of modest towns in Argentina.

Across Latin America, governments are building giant industrial complexes, oil refineries, gold and copper mines, and major transportation corridors, promising national development and funding for social policies. The phenomenon is known as redistributive extractivism: forests are razed, aquifers drained, and mountains mined to finance welfare and employment programs aimed at reducing poverty, even as environmental degradation increases it. Venezuela, Bolivia, and Ecuador, under left-wing governments, have increased oil and mining production.

Some “megaprojects,” like Brazil’s capital city, Brasilia, built from scratch on highlands once home to indigenous communities, are symbols of state power. Brazil’s current president, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, despite promising to protect indigenous rights and the environment, is promoting a railway through indigenous Kayapó territory that would deforest vast swaths of the Amazon. He is also promoting a highway through pristine rainforest and a giant dam that has decimated river ecosystems. Mexico’s self-proclaimed left-wing government has over the past four years likewise signed off on a dozen major projects, including a huge railway network in traditional Maya territory, a massive oil refinery, a major gas power plant, and a militarized-industrial corridor along a four-track railway linking the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans that Andrés Manuel López Obrador, the country’s current president, says would develop the poorer southern regions in Mexico. Argentina’s extractive projects boomed in the 2000s, as the country transformed its economy to become one of Latin America’s leading producers of silver, copper, gold, lithium, and oil. Around forty percent of Argentina’s oil production comes from Patagonia, the region just south of Bahía Blanca.

Sandra, Gabriel, and I dined at Gambrinus, a restaurant rated highly for its traditional Italian-Argentinean dishes. At the time, Sandra was investigating the government’s tax policies and public expenditures for La Nación, a national daily; in the following years she would contribute reporting to the Panama Papers and Paradise Papers, which leaked some of the global elite’s offshore and secret bank accounts. Gabriel reported on Bahía Blanca’s local affairs for a university radio station, a hyperlocal online magazine that he and Sandra cofounded called Solo Local, and Clarín, Argentina’s largest media conglomerate. Sandra’s daughters studied in Bahía Blanca’s well-reputed universities. She praised the city’s museums and shopping, but she told me the most important issue in Bahía Blanca—hardly reported nationally or internationally—was the pollution. “The city I grew up in is heavily contaminated,” she said. After our dinner of imported fish, they insisted on taking me for a drive.

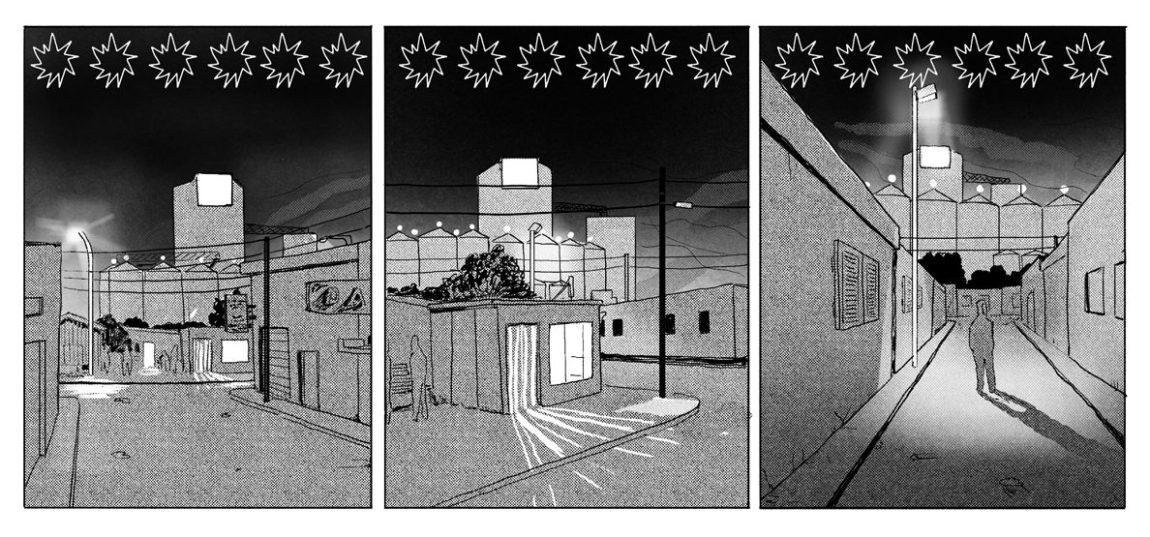

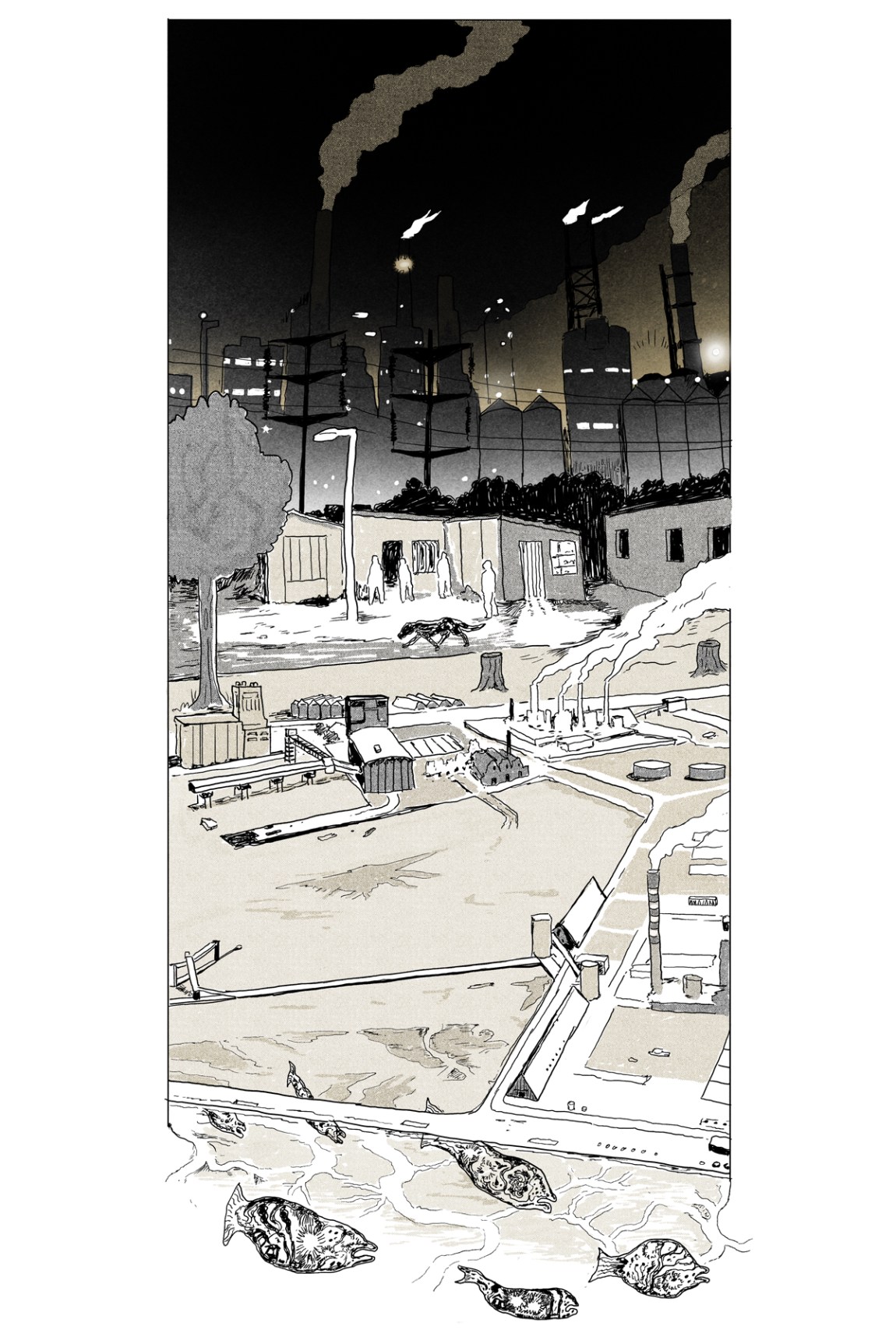

We passed the slim wooden changing cabins on the beach, mainly for Argentinean tourists, before the landscape opened up to wide roads, warehouses, and industrial parking lots. Just outside the city, Sandra parked the car next to a factory bristling with intertwined pipes. Flames twisted audibly, like a sharp wind, atop its chimneys. Orange halogen lamps lit the plant against the sky. Sandra told me that this industrial zone, a township called Ingeniero White, houses over a dozen petrochemical, fertilizer, and grain factories, some of them the largest of their kind in the world. It is, she said, one of the most polluted places in Argentina. I decided to relocate.

Gabriel dropped me off the following Sunday. I had a backpack for my computer, some environmental reports, and a bag of clothes. As we drove past the factories I heard gases scream through the metal. The clanging and whirring never grew distant, even as we left them behind. Gabriel rolled up our windows and tuned the radio to a classical station.

I had rented a house on a street of single-story rowhouses, two blocks from a giant fertilizer factory. I opened the door and sniffed the air. I saw fluorescent orange and green lights atop factories. Indoors, cracks ran up the walls and across my ceiling. The windows had been kept shut, and I was unsure if I should open them. Then I smelled the corrosive ammonia, crisp and pungent.

Advertisement

*

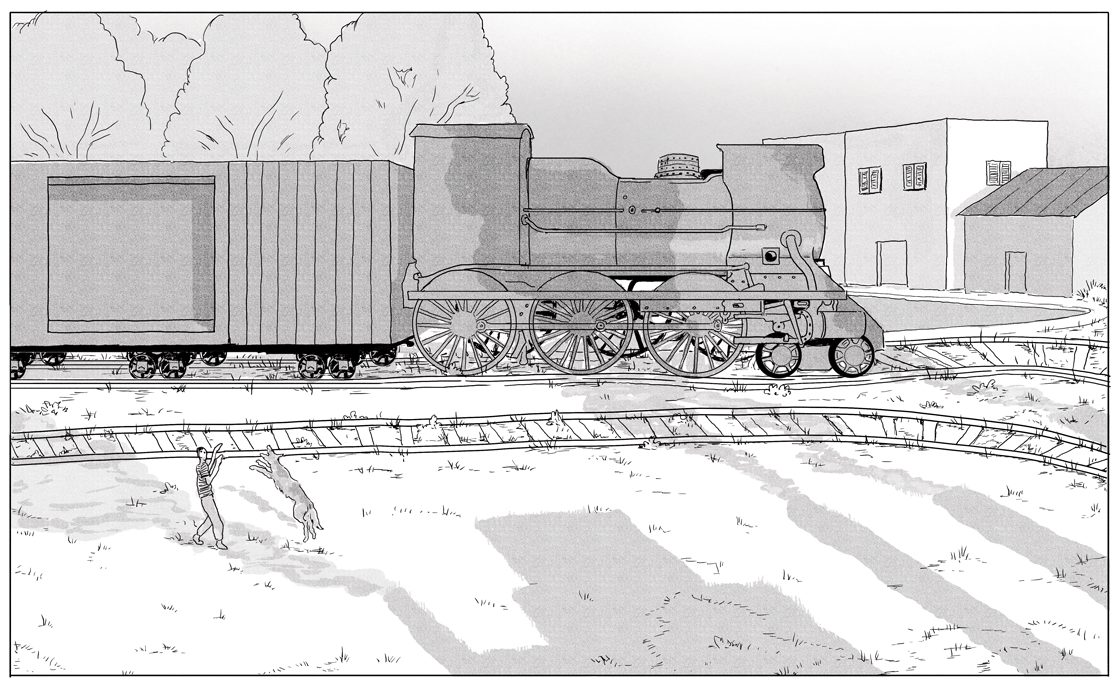

Bahía Blanca is named for the salt deposits on its shores, the protected habitat of burrowing grapsid crabs that build caves in the estuary during low tide. When crabs scurry out of their caves, the radiant white beach exposes them. The Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan searched this estuary in 1520 for a passage to the Pacific. He named it the “flooded shallows” before he eventually found, further to the south, his eponymous strait. Bahía Blanca served as an outpost for invading European colonists. The city’s outskirts were settled in the 1820s as the Puerto de la Esperanza, or the Port of Hope. In 1899 the Argentinean president rechristened this township after a prominent Argentinean engineer, Guillermo White. For decades Ingeniero White operated as a grain terminal, exporting wheat, corn, and barley brought in by train from the surrounding Pampas, Argentina’s vast expanse of fertile grassland.

Ingeniero White’s economy exploded in the 1980s when new gas reserves were developed in the Patagonian province of Neuquén, about 300 miles to the west. Dredging Bahía Blanca’s deep bay allowed large ships to dock in its port. A petrochemical industry developed around factories built by the Belgian chemical multinational company Solvay, the Canadian crop input supplier Agrium, and the US chemicals giant Dow. In the 1990s Argentina’s president, Carlos Menem, following Ronald Reagan’s example in the US, introduced a deregulated and low-tax corporate regime. Over the last decade, private investments have transformed Ingeniero White’s petrochemical cluster into one of the largest in South America. Each year it refines four million tons of natural gas and crude oil derivatives, and manufactures more than three million tons of petrochemicals—nearly two thirds of Argentina’s petrochemical production in recent years—and 350,000 tons of chemicals such as chlorine and sodium hydroxide.

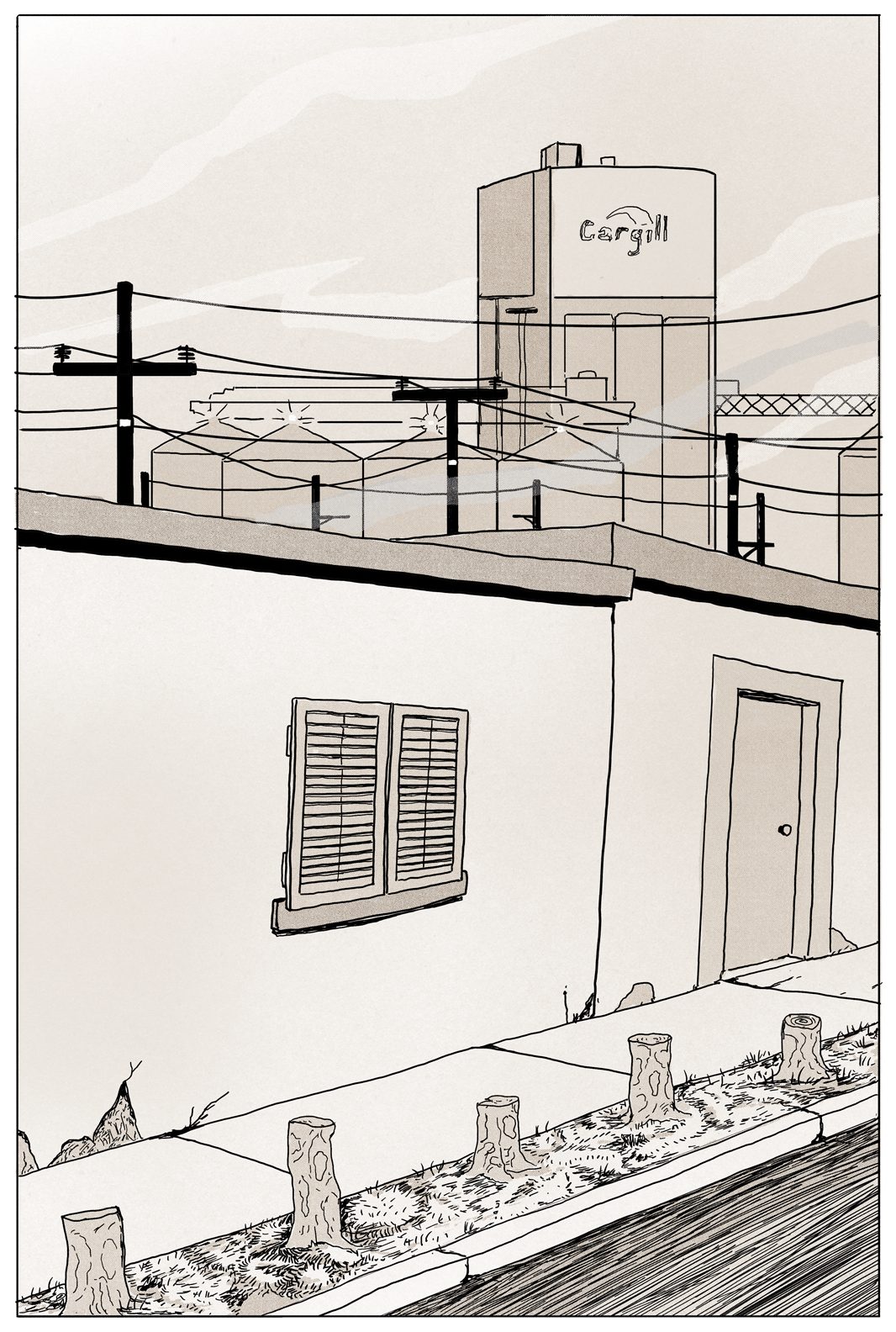

It is a township dedicated to essential twenty-first-century products. Dow manufactures ethylene for plastics here, as does Solvay, which also produces chlorine and polyvinyl chloride. An oil refinery is owned by the Brazilian giant Petrobras, and Louis Dreyfus, Cargill, and Bunge have set up grain terminals. The Canadian company Nutrien, formerly named Agrium, and the Spanish oil giant YPF own Profertil, whose megafactory produces granulated urea (a fertilizer used on industrial farms) and liquid ammonia (used as a refrigerant and in the production of explosives and textiles). Mega—co-owned by Dow, Petrobras, and the Spanish company Repsol—produces natural gas, propane, and butane to supply Ingeniero White’s other megafactories. Argentina’s government recently proposed expanding this complex with a new megaplant to liquefy gas from the Vaca Muerta formation in Neuquén, now the site of the world’s second-largest known reserves of shale gas, extracted by fracking. Just beyond these factories lie the limits of a marine reserve.

Bahía Blanca’s toxicity is public knowledge: a local joke casts Ingeniero White as the Springfield of Argentina, after the polluted town in The Simpsons. “We live in a contaminated city,” said Horacio Romano, an internist at Bahía Blanca’s municipal hospital and professor at its National University of the South. Several studies have confirmed the local pollution. Fish and crabs in the bay have been found to contain hazardous mercury concentrations. University researchers detected carcinogenic cyclic hydrocarbons in coastal sediments. From open-air gutters and effluent channels around the factories, extraordinary levels of heavy metals seep into the soil. Bahía Blanca’s doctors have reported elevated rates of inflammatory respiratory diseases, cancers, and tumors.

Local newspapers rarely mention this contamination. Some three thousand people are employed, directly or indirectly, by the industries, but many more benefit from Bahía Blanca’s economic development. The city’s daily paper, La Nueva Provincia, has a conservative bent that was reinforced when a businessman with strong industrial ties acquired it in 2016. The paper reported extensively on the benefits brought by the companies: technological innovation, skilled and unskilled jobs, and stimulus for the provincial economy. In the copies I picked up in 2015, articles cited Bahía Blanca’s uptick in traffic jams as signs of the city’s growth and relayed exciting rumors that Dow might hire more people to increase its local ethylene production.

*

I spent my second night in Ingeniero White thirsty. My landlord, Alejandra, had generously left a kettle and chamomile teabags on my kitchen countertop, but no drinking water. I had forgotten to buy any, and the shops had shut early. As my bedroom heated up I lay in bed, my throat parched from the fumes that seeped around my shuttered windows, and debated whether to drink the tap water, as some locals did, even though Sandra warned me that it contained heavy metals. I marveled at the feats of engineering that kept the factories lubricated and cool so that they ran night and day. When I concentrated, I heard their roar, like white noise.

Advertisement

In a park the next afternoon I met a boat captain, Juan, beside an abandoned antique British train engine. Juan played with his German shepherd in the brown organic residue from the Cargill cereal factory, which littered these streets like dead leaves. “Do you know any industry that does not pollute?” he asked. “Of course this place is contaminated, but my job gives me a good life. I come from a poor family and these plants bring me hope.”

The façades of Ingeniero White’s houses were fissured like jigsaw puzzles. Their foundations had shifted, and the roofs had slid apart at their highest points, leaving gaps overhead that let in the light and rain. Walls leaned precariously, and walking past them I felt they might fall on me. Wooden shutters were sealed tight. Having not yet seen an open window on my block, I asked my neighbor Graciela if these houses were abandoned. She invited me into her home and asked me to pull open her window. The glass would not slide, even when I leaned with all my weight. She told me that the windows no longer opened because the moving earth had shifted the walls. Juan Pedro Compagnucci, a civil engineer who repaired local homes, told me when I visited his offices that the ground in Ingeniero White was unstable. In order to lay pipes and build thick columns for the factories’ foundations, the companies often drained the groundwater from a large area. The soil lost humidity and collapsed on itself, falling away in sinkholes on the streets and beneath houses.

Graciela was a tender woman whose smile was betrayed by her anxious eyes. Sixty-three, with dyed blonde hair, she had grown up in Ingeniero White before working a few years as a reporter in the Bronx. She was one of the few locals who openly protested against the companies, organizing community meetings and giving interviews. Sitting in her dark living room, she recited the names of the chemicals the factories emitted and showed me thick black folders of scientific reports documenting their health hazards. I asked why she lived here. “I came home,” she said. “We all have to return to our roots.” What about her eight-year-old granddaughter, who lived with her? Over a cup of warm mate, I ventured that, as the young girl was not from the town, she did not need to live here. Surely it could not be good for her health? Graciela shifted in her seat and, avoiding my question, said, “I’ll show you something.”

She pointed at some wooden stumps in front of her door. She had cleared the eucalyptus around her property. “I want all the trees removed,” she said. “They collect toxic dust on their leaves, and when the wind blows the toxins come at you.” It was as if the trees in Ingeniero White breathed poison instead of oxygen. “In a petrochemical city, you have to make difficult choices,” she said. “If you can’t get rid of the factories, you get rid of the trees.” A drizzle started. Graciela told me the rain was good because it washed the leaves clean, even if the toxins then contaminated the soil.

I retreated into my house and watched a news report about a woman’s dog that had fallen into one of Ingeniero White’s effluent pools. The dog was blinded by the caustic soda and ammonia, but it returned home by instinct, still foaming at the mouth. Its owner said that no one in the town cared when she told them, even when she pointed out that what had happened to her dog could also happen to a child. That story was a rare reference to the pollution on the local news. Residents of Ingeniero White reported ever fewer birds, bees, and bats. On the city’s walls they had painted murals of flamingoes, birds, and fish. I caught Graciela one morning looking for fish in a pool of water near a factory. “I am looking for a sign of life,” she told me. “This pool has been here for years. There are always small fish in a pool of water, you know?”

*

The local history museum offered perhaps the only public indication that anything was wrong in this town. Beside an old wooden fishing boat, kitchen artifacts, and nineteenth-century factory relics like wheels, anvils, shafts, and gears, as well as engines once used to transport and export Patagonian grain, a small plaque stuck into a patch of bright green grass announced:

The air you breathe is not normal. It has a story that goes back to the first Industrial Revolution. Inhale: in it are particles of cereals and emanations of petrochemical plants, the millions of volatiles of production.

Among all the antiques, this plaque read like old news. I asked the museum director, an elderly man named Leandro, about it. “We don’t want to sound as if we are complaining about the companies,” he said.

That evening I was invited to dinner by Alejandra and her teenage daughter, Oriana, who set out cheese empanadas and chimichurri. “We live in the pollution like it is normal,” Oriana said. She had spent her entire life in Ingeniero White. The megafactories intensified their activities at night, Alejandra told me, running their machines at a higher capacity when residents were less likely to notice. Halfway through our meal, Alejandra bunched up her nose. Her vaporizer, which punctuated our conversation every ten minutes with squirts of perfume, had run out of scent. Now we smelled the chemicals and the ammonia. Alejandra replaced the vaporizer’s canister of lavender, which she hurriedly sprayed around the living room. “Do you like the smell now?” she asked Oriana. “I love it,” she replied.

Walking home after our meal, I stared at Profertil’s megafactory. Its chimney stood only fifty meters away, its cream-colored smoke lit by a flare. A man with a heavy beard emerged from the shadows on my street corner. The wind had turned, he told me, and the smoke was coming toward us.

The itch in my throat worsened over the week. I was getting ill. I swallowed a painkiller and then an antihistamine. I began to doubt if my research was worth risking my health, and wondered whether I was increasing my chances of developing cancer decades later. But I decided to stay in town a few more days. Sandra and her friend Oscar Liberman, an economics professor at the National University of the South, had invited me on a boat trip on the bay, so I could see how the petrochemical plants affected the coast.

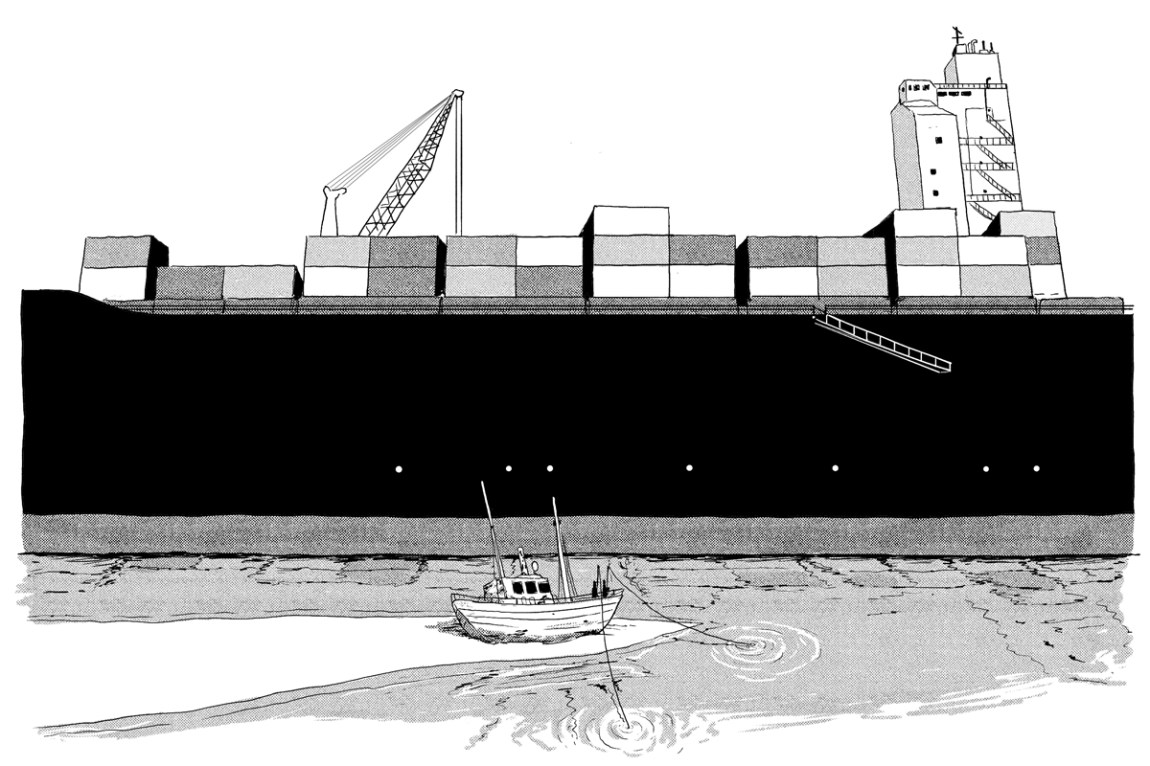

Swirls of effluents lent their fluorescent rainbow colors to the water. Our boat was dwarfed by ships docked near the factories, carrying chemicals and grain. We smelled the stink of gas and acid. But the bay was good for sailing. For its harsh winds and salt, Bahía Blanca used to be called La Tierra del Demonio (the Land of the Demon) by indigenous peoples, whose communities—including the Mapuche, Tehuelche, and Ranquel—were nearly wiped out in the 1800s, in an extermination campaign led by President Julio Argentino Roca. An old version of the hundred-peso bill, still circulating everywhere, celebrated his genocidal “Conquest of the Desert.”

Some Mapuche still live in Patagonia near the Vaca Muerta shale gas formations. Like most of Argentina’s indigenous people, they are nearly absent from national politics, popular media, and the market economy, and are derided as lazy and savage. Last year the Mapuche mounted roadblocks to protest the hundreds of fracking wells—illegal in many countries—that contaminate the air, water, and land. They report unusually high rates of cancer and miscarriages, as well as farm animals born with strange defects.

Environmental defenders who challenge what they call proyectos de muerte (projects of death) are maligned as “antidevelopment” and brutally repressed. They say their communities have become enslaved to factory jobs and dependent on bottled water after industrial projects contaminated their precious underground aquifers. Often carrying only machetes and hoes, they blockade highways and occupy government buildings. Over the last decade, according to the nonprofit Global Witness, of the more than 1,700 activists defending forests, rivers, and aquifers who have been killed around the world, two thirds were murdered in Latin America. Argentina accounted for seven of these killings; in 2021 the Mapuche defender Elías Garay was shot dead by armed logging company employees. In much of Latin America, deaths and arrests of foreigners and urban elites are more likely to make the national news, while crimes against the indigenous feature less prominently, or not at all.

Decades before the Conquest of the Desert, around the time of a previous Argentine campaign to conquer the Pampas, the HMS Beagle anchored in Bahía Blanca’s estuary. Charles Darwin wrote of that 1832 stop:

The wide expanse of water is choked up by numerous great mud-banks, which the inhabitants call Cangrejales, or crabberies, from the number of small crabs… I employed myself in searching for fossil bones; this point being a perfect catacomb for monsters of extinct races.

The old beach has long since been built over, and in 1998 Greenpeace sued the companies operating in Bahía Blanca for dumping toxic industrial waste into the estuary. The lawsuit took twenty-three years to process. When it concluded in 2021 only a symbolic penalty was imposed on a former Dow manager who no longer worked there. Around 2010 dozens of fishermen brought another lawsuit, claiming that the dramatic decline in the estuary’s marine life was caused by the factories’ toxic waste and untreated sewage. Argentine courts have yet to determine if the fisherman should receive any damages.

We sailed past an abandoned boat, stranded on a sandbar and covered up to its chimney in thick rust. Two men sitting on its prow held fishing poles. The sun was bright and the breeze cool. I scanned the water and breathed deeply, sniffing for unusual odors.

For twenty years Sandra and Oscar had reported on Bahía Blanca’s contamination. In 1991 and again in 1993, Sandra sent seawater samples to laboratories in Buenos Aires, which detected high levels of mercury, cadmium, lead, and zinc, but her editor at La Nueva Provincia refused to publish her findings. “I will never forget how he explained it,” she said. “He told me, ‘It’s not called pollution. It’s called progress.’” The companies bought advertisements in the paper and on local radio stations. Sandra said they pressured editors to reassign reporters from sensitive stories and sometimes influenced journalist hiring. “Reporters are silent because they fear losing their jobs.”

Our boat rode the wind, then ran into a sandbar. Oscar turned the engine to full throttle. It belched out a cloud of smoke that enveloped us. As we sailed past the complexes of shining pipes and the chimneys spewing bright white smoke, I noticed a recreational sailing club nestled between the megafactories. In 2021 Bahía Blanca dredged Ingeniero White’s port to allow ships even fifty feet deep in draft to dock and supply the petrochemical complex, while exporting its outputs to global markets along with Patagonian oil, fruit, and wool.

A fisherman I met at the port, Omar, said he knew the fish he sold were contaminated, though the government insisted that certain varieties from the bay were safe to eat. Locals wouldn’t buy his catch, he said, “but in Buenos Aires people eat my fish as if it’s the best in the world.” I asked why he fished in contaminated stocks. He placed his palm on his belly. “I have to earn a living. Listen, everyone here pretends that the pollution is not a problem. It is easier for me to also pretend.”

*

The property of a gas is to seek to disperse. Molecules move randomly and rapidly, causing countless collisions each second. Air constantly collides with each exposed portion of our bodies and with our lungs. Chlorine, a halogen not found in nature, is one of the most reactive and corrosive known gases, used at low concentrations as a disinfectant and at high concentrations as a chemical weapon. Only seven outer electrons orbit its nucleus, missing the one that would complete its shell. Seeking this missing electron, chlorine will attack almost anything it touches, destroying cell membranes, entering cells, and disrupting DNA activity essential for cellular survival. In 2000 a chlorine leak from the Solvay factory was followed by an ammonia leak from the Profertil factory. A school and a sports club were evacuated, though deaths and serious injury were averted by the wind, which, by good fortune, carried the dangerous gases out to sea.

My neighbor, a middle-aged cancer patient who had been told he had a few years to live, showed me a television clip in which his oncologist, Gustavo Salum, spoke about the unusually high rates of leukemia and lymphomas in Bahía Blanca. The doctor was alarmed at the rising number of lung tumors normally associated with asbestos in people who had not been exposed to it. “There isn’t much asbestos in the city of Bahía Blanca.” He was recording between twenty-five and thirty-five cases each year of rare and fast-growing sarcomas, which had barely existed in the city ten years ago. He saw four to six new cases of pancreatic cancers every month, a “very high” rate. “Un tumor agresivo,” he said. Two or three tumors had been diagnosed in each township block near Ingeniero White. He cited the contamination from the megafactories as a likely cause, and said seventy percent of megafactory managers did not live in Bahía Blanca. He shrugged and said, “What’s the implication?”

I made an appointment with Salum. But in the morning, just as I was about to leave for his clinic, his secretary called to say that the doctor had to cancel our meeting to deal with an emergency. I still showed up and found the waiting room was full. There was no sign of an emergency. His secretary said the doctor did not wish to speak to me, not even on another day. “I don’t know how to tell you,” she said when I asked for a reason. At that moment, Salum opened his door to see out a patient, and our eyes met. He appeared hesitant and sad. “You don’t want to speak?” I said. He paused, then shut himself inside his office. As I walked away, the secretary followed me.

“They threatened him,” she said. “We have investigated for years, and no one can prove anything.” I asked for more information, hoping she would clarify that the companies were responsible. She opened the clinic’s door and showed me out.

It was impossible to confirm, but Sandra and Graciela told me the rumor: that after his television interview, the doctor had driven out of the hospital parking lot one day and discovered he could not stop his car. Someone had cut his brake line. He took it as a warning, stopped speaking about the factories, and focused on treating the sick.

*

It was during my second week that I could almost begin to see myself living here. A cyclist in a red suit passed in front of my house. A mother walked behind him carrying her baby against her breast.

The Executive Technical Committee (CTE) of Ingeniero White is housed in a two-story building filled with laboratories, biologists, technicians, surveillance staff, and cameras. Data is collected from sensors across town that monitor air, water, and even the factories’ noise levels. The committee was created after chlorine and ammonia leaks in 2000 sparked protests. Local laws were passed to protect people, and the CTE was tasked with monitoring the companies’ compliance with environmental regulations—to ensure, for example, that industrial waste sent into the estuary was treated first.

César Pérez, a former Dow employee, was the committee’s coordinator when I visited its offices—glaring evidence of the revolving door between the companies and government. In his control room, Pérez showed me a row of computers that displayed levels of ammonia, chlorine, and smoke in Ingeniero White. Screens flashed with line graphs and bar charts. Maps indicated the sensors’ positions. “More sensors would be better,” said Pérez. “We will eventually have more sensors.” Pointing at the screens, he told me that the mercury, cadmium, lead, and other heavy metals in the water and in the pools outside the companies were “at normal levels.” So was the carcinogenic vinyl chloride monomer emitted by the companies, and the hazardous ammonia and chlorine.

I asked if it was normal to breathe ammonia. “Es normal,” he said. “But in the mountains a hundred kilometers away there is no ammonia,” I said. “There wasn’t ammonia in this city before the companies arrived. How can ammonia be normal?” He clarified: “Es inevitable.” A woman wearing a white laboratory coat entered the building carrying bottles of effluent from the factories’ discharges into the sea. She showed me the readings she had noted on a checklist. “How are things?” Pérez asked, apparently anxious that they might record excessive toxicity in the presence of a reporter. “Everything is normal,” she cheerfully replied.

When the committee recorded that companies had violated the limits, the province had the authority to issue fines. But Buenos Aires had to approve any proposed sanctions, and the distance and bureaucratic burden meant that the companies were often let off the hook. Criminal and civil lawsuits against Solvay and Profertil for the major leaks had produced no penalties. Results from the CTE’s factory inspections were no longer published, nor were minutes from the meetings of the Control and Monitoring Commission. The government was supposed to inform the local community about its findings from inspections, but mostly failed to do so, without legal consequences. Local authorities meanwhile praised the companies’ tax contributions, employment, and charity.

Still, Pérez assured me that more studies would be conducted to investigate the chemicals’ effects on humans. Harmful elements would be limited to benign levels. I told him that I had smelled ammonia inside a car on my way to Ingeniero White. He checked his registers against my report’s date and time. The committee had recorded no leak on that date, he said, nor had anyone called to file a complaint. The sensors had not registered abnormal readings. Pérez insisted I had little reason for concern. Asked about contamination in the bay, he said that “the bay is not contaminated.”

“I would use the word ‘impact’ instead of ‘contaminate,’” he offered. “There has been an ‘impact’ on the bay.” A biologist working with Pérez agreed that “contamination” carried an unhelpful connotation. “The words you use can influence how you feel about things.”

*

Sandra asked if I would share my observations about the contamination on a popular Bahía Blanca radio show run by her friend. “It helps to educate people, especially when an outsider makes an independent report,” she said, since local journalists were reticent. I too wanted to share my findings. The station’s owner, Diego Salvadori, was one of the few local journalists who didn’t accept the megafactories’ advertising sponsorships. On a live broadcast I told him that Bahía Blanca had become financially dependent on polluting corporations, that the government appeared to be corrupt, and that many locals quietly consented to the new order. As if to prove me correct, once the broadcast was finished our translator, Mariana Viney, told me, “I’m not against the factories. They provide us with employment. I could develop a third eye from the pollution. So what?”

After the interview I trudged back to my apartment. The houses were mostly dark, but in places, through cracks, I glimpsed a light, or a person sitting still. I passed the port, the waters we had sailed, and the field with the antique train engine. A dim lamp glowed inside Graciela’s house. A truck drove by, tossing the cereal factory’s residue into my hair. At home, I opened the door to my bathroom and was hit by a rush of ammonia. I choked, afraid to breathe. My eyes watered. I shut the door and kneeled. From my bag I drew a cotton towel that I wrapped around my face. It was time for me to leave.

I checked into an old hotel in Bahía Blanca’s city center. Its staircases were wide, its ceilings high, and its bedrooms spacious and carpeted. The bathroom fittings squeaked. The Wi-Fi was unreliable in my room, and so, mostly disconnected, I spent those few days in a trance, recalling my stay in Ingeniero White and wondering if I had harmed my health. I read my father’s tattered copy of Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance. The hotel’s restaurant was closed, so I bought cheese and spinach empanadas at a small tienda down my street. I worried that my hair might have absorbed chemicals, so I had an elderly barber down the street trim my hair down to a few millimeters.

Before I left Bahía Blanca, an air force meteorologist named Fabian, a friend of Diego, offered me a flight over the city. “You can photograph the petrochemical factories,” Fabian told me. “They are impressive from above.”

Bahía Blanca’s single-story aero club featured a plaque dedicated to a famous visitor and “amigo,” Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, with engravings of his World War II propeller plane and of the famous character from The Little Prince. Fabian checked a meteorological report. A few lonely nimbus clouds towered above us, but conditions were otherwise clear. Climbing into the Cessna training aircraft, decorated in burgundy, I noticed that the pilot and I each had a yoke to steer it, but I was careful not to touch mine. The pilot, a friend of Fabian’s, turned the dials to adjust the aircraft’s controls and pushed the engine to full throttle. We lifted off.

We flew over Bahía Blanca’s estuary, making a wide arc over grassy plains until we turned to face the coast—the horizon of blue meeting blue. From above, I better grasped the scale of the petrochemical complex, a city unto itself dominating the curve of the estuary. Chimneys smoked white below us. “Beautiful day!” the pilot yelled over the engine’s noise. Container ships, docked in deep water at a distance from the port, connected to factory supply pipelines before traveling back into the Atlantic, headed for the United States and China. I spotted my neighborhood of low houses, a speck alongside the factory complex, and the streets where Graciela’s house, the old railway, and the museum must be. Peering out of my small side window, as the pilot turned, I searched for Alejandra and her daughter.