Influence is mysterious—we’re so rarely aware of who or what moves the levers inside us. There are the influences you and I claim, the ones we are conscious of, the teachers we seek out. And then there are people like E.T.A. Hoffmann, the nineteenth-century German Romantic writer, composer, and artist. Considered by many to be the godfather of modern horror and fantasy, Hoffmann’s influence turns out to be everywhere, and like pollen dispersed in the atmosphere it often goes undetected. His uncanny tales have been so thoroughly assimilated into popular culture that he now exists in what the Italian folklorist and fabulist Italo Calvino called “the mute and anonymous molds of thought.”

When the artist Natalie Frank recently asked me if Hoffmann was an influence on my fiction, I sheepishly admitted I was not familiar with his work. But I was wrong; as it turns out, Hoffmann is one of the great-grandfathers of my imagination. Frank sent me the drawings she’d made to accompany Jack Zipes’s new translations of five of Hoffmann’s most famous stories: “The Golden Pot,” “The Sandman,” “The Nutcracker and the Mouse King,” “The Mystifying Child,” and “The Mines of Falun.” I loved the drawings, with their lurid subversions of conventional notions of ugliness and beauty, their tonal alchemy of the miraculous and the everyday, dreamlife and daylight: a woman with an exquisitely realistic face rests her temple against a looming blue double; two cartoonish men are sealed inside glass bottles on a desk, a serpent’s tongue lying flat as a legal brief beside them. Unlike traditional storybook illustrations, Frank’s drawings do not depict events from these tales so much as dramatize what a fairy tale becomes under the waterline of waking consciousness.

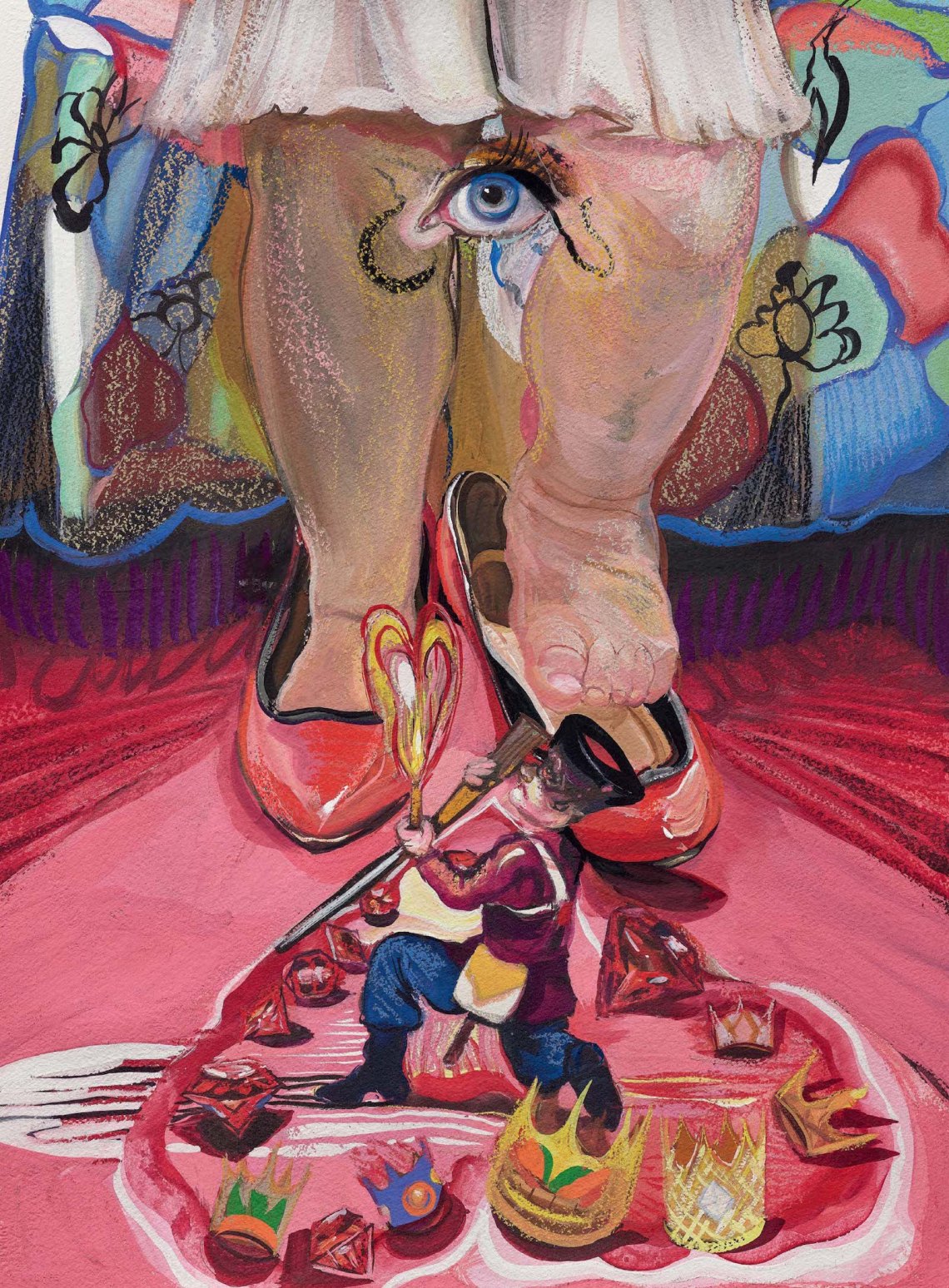

One drawing jolted me with déjà vu: a young girl stands in her bedroom, where Frank’s swirling layers of chalk and gouache evoke both melting candy hearts and dripping blood. A toy nutcracker kneels at her feet, offering her his heart. Plumes of scarlet dance around the margins, where dead mice bare their teeth. Only the girl’s lower body is visible. One pudgy foot has lifted out of a slipper. A disembodied eye hovers in the libidinal shadows between her legs. Reading Hoffmann in this oblique way, moving through Frank’s conjurations into his prose, I began to understand the extent to which my own imagination has been shaped by his stories of artificial intelligence and sinister alchemists, shadowy doubles, dolls that come to life, sublime forests and subterranean kingdoms.

As Zipes laments in his introduction to The Wounded Storyteller, “Paradoxically, in the western world, Hoffmann is celebrated mainly at Christmas, as the author of the ‘sweet’ glistening ballet The Nutcracker and the Mouse King. However, the ballet was not based on Hoffmann’s story, but on Alexandre Dumas père’s adaptation.” The horror of the original comes not only from seven-year-old Marie’s nocturnal battle, but from the way her experience is dismissed by everybody she loves as “nonsense” the following morning. Madness, Hoffmann suggests, may not always result from a traumatic event itself but from the loneliness and doubt it leaves in its wake. Madness can come at dawn, when you discover that your nightmare belongs to you alone.

“The Sandman,” published in 1816, famously appears in Freud’s essay on the uncanny as the exemplar text. Hoffmann’s Sandman is not the sweet Nordic fairy who sprinkled magic dust into the eyes of insomniac children, in the dark ages before the invention of melatonin gummies. He is a diabolical alchemist who flings flaming sand into people’s faces and steals their eyes. One night, a frightened young boy named Nathaniel spies on his father assisting the Sandman in his ghastly trade. Young Nathaniel recognizes this unholy tormenter through a veil of smoke: by day he’s the lawyer Coppelius, with whom his father sometimes has lunch (Hoffmann was a lawyer himself). The Sandman, brandishing red-hot tongs, tells Nathaniel’s father, “Time to start our work!” When the Sandman spots Nathaniel spying on them, his father pleads, “Master, master, let my Nathaniel keep his eyes! I beg you!”

There is something darkly comic to this terrifying scene, perhaps because it takes the shape of a familiar coming-of-age story. We hover on the threshold of comprehension with Nathaniel, a wide-awake child who cannot reconcile the goodness in his father with the evil of his work. “The Sandman” allegorizes the violence to which systems of domination bind us all as parts and labor, as victims and agents and bystanders. Here is the true horror of a story replete with it: “When my old father stooped down to the fire, he looked like some other man…. In fact, he looked just like Coppelius.”

Advertisement

Nathaniel’s father becomes indistinguishable from the Sandman. The men use tongs to remove open eyes from the faces melting in a grate. It’s a scene of supernatural terror, which on its surface seems too gruesome to credit as “real.” Yet you could also read Nathaniel’s midnight vision as the child’s lucid understanding that his beloved father is part of a system of capitalist extraction that turns people into commodities. Hoffmann uses the uncanny to awaken his reader to the threats that beset us from without and within:

If there is a dark and hostile power that lays a treacherous thread within us, holds us tightly, and draws us along the path of peril and ruin, a path that we would not have taken—if I say there is such a power, then it must form itself inside and out of ourselves. Indeed, it must become identical with ourselves. Only under this condition can we believe in it and grant it the room it requires to accomplish its secret work.

In the morning Nathaniel is told to forget what he saw. The smiling complacency of the adults around him, and the tacit instruction to put out one’s eyes, is also part of what makes “The Sandman” a horror story. As an adult, Nathaniel goes on to become a victim of the optician Coppola, a doppelganger of Coppelius who tricks him into believing that a lifelike automaton is a real woman named Olympia. This hot robot with perfect pitch passively seduces Nathaniel, who projects his fantasies onto the female doll; when he discovers that she is made of glass and lumber, his mind shatters. The Sandman has robbed Nathaniel of his ability to distinguish between humans and machinery, inner and outer reality. Eventually, Nathaniel tries to fling his warm-blooded fiance from a tower, convinced that she too is a wooden doll. He sees (or perhaps hallucinates) the Sandman watching him, and jumps to his death.

Who among us survives childhood with their eyes intact? Nathaniel’s encounter with the Sandman finds resonances in Hawthorne’s story “Young Goodman Brown,” published two decades later in 1835, another young voyeur’s terrified recognition of the world of evil to which loved and trusted adults have signed on. I find myself astonished by how far Hoffmann’s voice has carried, echoing through the works of Stephen King and Jean Baudrillard; Gogol and Poe; Joy Williams’s The Changeling and Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower; the erotic feminist fairy tales of Angela Carter and the spiraling utopias of Ursula K. Le Guin; the female automata in Philip K. Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? and the humanoid Cylons in Battlestar Galactica; the soulless shell of Donald Sutherland in Invasion of the Body Snatchers and the wise children in The Night of the Hunter; David Lynch’s doppelgangers and Jordan Peele’s Us; and the scariest episode of Black Mirror, in which a sadistic programmer traps replicas of his colleagues’ consciousnesses in a virtual world that he controls. Hoffmann’s nineteenth-century tales feel so relevant to the challenges we face in the twenty-first century, confronted by the uncanniness of deep fakes and ChatGTP love poetry and the tech oligarchs at Google and Twitter and Apple and Facebook who are insidiously automating our desires from within, encouraging us to uncritically accept their terms and conditions.

Even if you believe that you are new to them, these stories know you. If you have ever been the child who feels so alone with what she knows, the bumbler whose “buttered bread always [falls] to the ground on the buttered side,” the wanderer who hears a secret song in the woods, the romantic who struggles to be taken seriously, then you will find yourself in the enchanted mirror of his work. You might meet, as I did, one of the secret authors of your dreams.

*

Ernst Theodore Amadeus Hoffmann was born in 1776 in Königsberg, Prussia, now Kaliningrad, the youngest son of unhappily married cousins who abandoned him to the care of an unfeeling uncle. He worked as a law clerk and a judge in Germany and Prussian Poland. Unsteadily employed by a dissolving bureaucracy during the era of Napoleonic occupation, he became familiar with hunger and exile, ridicule and failure; his cartoons mocking military officers once got him “promoted” to a station in the Polish hinterlands. In addition to being the progenitor of the modern gothic and the detective story, he was a brilliant composer and music critic. He wrote his two most famous works, “The Golden Pot” and the opera Undine, in 1813 and 1814 while in Dresden, and then spent a prolific half decade in Berlin, where he ran a salon attended by poets, physicians, theologians, musicians, and statesmen that inspired his four-volume anthology, “The Serapion Brethren,” which was adapted by Wagner and Offenbach. His artistic and legal careers had nosebleed highs and catastrophic lows; he died of syphilis at the age of forty-six.

Advertisement

Hoffmann worked during the upheavals of imperial wars and the first industrial revolution, in the wake of Enlightenment advances in science that seemed to suggest people lived in a mechanistic, deterministic world. The Voltaic battery had arrived on the scene, supplying its fantastically steady flow of power, along with electric lamps and the steam engine. Vitalism and hypnotism were studied alongside the physics of “imponderable fluids”—heat and light, magnetism, and electric current. It was a time of many discordant and contradictory theories about the laws and substances of nature and the workings of the mind.

The early Romantics repudiated the nihilism of aggressively reductive materialism, and while they are sometimes caricatured as dreamy pagans in flight from reason, in fact they were engaged in a helical dance of mutual influence with empirical investigators—the chemists, the biologists, the astronomers, the physicists, the geologists—who also sought to comprehend the underlying nature of reality. Art and literature were for the Romantics a cartography of unknown realms, including the vast and unmapped territory of the human psyche. Hoffmann the fantasist asked the same questions about knowledge, mind, and matter that obsessed the scientists of his time, many of whom looked to illusion, phantasmagoria, and artifice to teach them about how the mind identifies and categorizes certain phenomena as real. In every story he explores the authorial role of embodied consciousness in the theater of reality. He foregrounds the potency of the perceiver, treating the reader not as a story’s passive recipient but as its cocreator, often via direct address: “Gracious reader,” he implores us, “your active imagination, for the sake of Anselmus and me, will have to be obliging enough to enclose itself for a few moments in the crystal. You are drowned in dazzling splendor, and everything around you appears illuminated.” Reading is a waking hallucination, Hoffmann reminds us. When we read, we model a virtual reality.

A story can also be a kind of experiment, a counterfactual that reveals truths about people and the world. John Tresch writes that in the nineteenth century, fantastic literature and the positive sciences “traced the same journey in opposite directions,” linked in “a dialectic of doubt and certainty.”1 The writer of fantasy also evinces a “restless hunger for reality…bound up with skepticism.” In his fiction, Hoffmann relentlessly calls the testimony of the senses into question, exploring the hazy borders of the self and the world: Can we be sure we didn’t hear a bell-like voice in the woods? Was that moonlit apparition merely a symptom of exhaustion or intoxication? How do we know that the netherworld revealed by the “feeble glimmer” from a candle is any less real than Marie’s childhood bedroom on a Tuesday morning? By hesitating between possibilities, Hoffmann plunges his readers into a state of attentive humility. Like Elis in “The Mines of Falun,” watching the “walls of rock [grow] as transparent as pure crystal,” we are jolted by the limitations of what we can know for certain.

These irruptions of the fantastic occur in a Germany that follows rules we recognize. Even the wildest tales feature cash-strapped families and their everyday struggles. Rent comes due, abusive bosses freak out over minor mistakes, and children annoy their parents. A good day for Anselmus, the hapless hero of “The Golden Pot,” is a day when he doesn’t lose a button. Hoffmann stays just as attuned to his characters’ longing for the sublime as their more mundane appetites, like a Friday night beer with friends at the Linke Tavern. As a young clerk, Anselmus is torn between a life of middle-class stability and his “infinite longing” to transcend his circumstances and to know absolute truths. He falls in love with Serpentina, a singing snake-woman who invites him to follow her to the enchanted kingdom of Atlantis. She offers him the lily of knowledge and urges him to “perceive what is highest”: the laws of nature that both scientists and artists seek to comprehend. Serpentina is a glorious fusion of Eve and the serpent—she does not lead Anselums out of Paradise, but into it. When a witch shrinks Anselmus and traps him in a bottle, his supernatural predicament is also a metaphor for the claustrophobia of any dead-end job.

Actions have important and often irremediable outcomes: when Nathaniel leaps from the tower, the fall kills him. Yet in Hoffmann’s fusion of naturalism and fantasy, the Sandman’s heavy footsteps and red-hot tongs are described with the same fidelity as Nathaniel’s fatal collision with the stones. The pooling blue eyes of Serpentina are painted with the same numinous brushstrokes as the golden waves of the Elbe River. We begin to see the mystery that is always present with us, to which we have been inured. “The aspects of things that are most important for us are hidden because of their simplicity and familiarity,” Wittgenstein writes. “One is unable to notice something—because it is always before one’s eyes.” Uncanny literature has an extraordinary power to show us the horrors, the absurdities, the wonders, and the unknowns that fade from view as we age and grow resigned or benumbed to them. Hoffmann challenges the precarious binary of “reality” and “fantasy,” asking in both Dresden and Atlantis: What is true? What is possible? He reminds us that, at any moment, another reality might pierce the one to which we’ve grown accustomed, overtaking it and changing it forever.

For all his feverish inventiveness, Hoffmann’s true sorcery is his ability to transfer his characters’ private experiences into the reader. His stories teach us to respect the uncanny depths inside of any “ordinary” human being: “The miraculousness and strangeness of [Nathaniel’s] life filled my entire soul, and for this very reason, my dear reader, I had to make you just as inclined to tolerate the uncanny, which is no small matter.” They remind us that other people are as real to themselves as we are to ourselves. This really matters. Storytelling is the life-saving alchemy—turning flat words into blossoming worlds, and bridging subjectivities—that opposes our reduction to materials. When we become automata to one another, exploitation, madness, and violence follow.

The children in Hoffmann’s tales tend to emerge scathed but victorious from their battles with cruel adults and rodent kings, their faith in themselves and their imaginations intact, but the adults rarely fare as well. If enough people tell you that what you see and feel is not real, you might end up flinging yourself from the top of an ontological waterfall. Time and again Hoffmann’s characters wonder whether what they are experiencing is actually occurring in consensus reality or only unfolding in their minds. It is a difficult test to run in-house, without controls. The test ends tragically for Nathaniel and Elis, but it leads to new beginnings for those like Anselmus and Marie who learn how to travel between the world of noonlight in Germany and the spirit realm without getting lost in either.

A story can be a mirror of its author’s trauma, but it is not only that. Zipes, drawing on the sociologist Arthur W. Frank, describes Hoffmann as a “wounded healer,” someone who was able to transform his suffering into stories of exquisite consolation, compassion, humor, and invention. Although he is often associated with the macabre and the grotesque, fairy tales like “The Golden Pot” and “The Mystifying Child” open outward into what may be the most fantastical outcome of all: happiness. When the narrator of “The Golden Pot” laments that he is about to get booted from the story, no longer living in Atlantis but “transplanted to my garret,” the Archivist chides him: “Do not complain so much! Weren’t you just now in Atlantis?… And is the happiness of Anselmus anything else but life in poetry? Can anything else but poetry reveal the sacred harmony of all beings as the deepest secret of nature?”

For Hoffmann, it’s an open, genuine question. As a civil servant, he was himself transplanted to his garret; he could not take up permanent residence in Atlantis, and his longing for transcendence found its fulfillment in art. Yet like the luckiest and wisest characters in his fairy tales, he moved amphibiously between his dream life and his waking life. He is clear that his utopias—Atlantis, the emerald fairy realm of “The Mystifying Child,” the “sparkling Christmas forests” far from Marie’s family’s bourgeois home—do exist for his characters, as well as for him, their inventor. These utopias cannot be found on any map, but they direct us home to the boundlessness of our own imaginations. They are sanctuaries for creativity, and testing grounds for hypotheses. Hoffmann’s enchanted kingdoms exist outside of ordinary conventions and off the factory clock. Under their “emerald green leaves,” Hoffmann encourages us to open our inner eyes. If you’re like me, you may find it easier to imagine torture at the hands of an eye-thieving alchemist than the happiness of Atlantis. My own struggle to envision utopias strikes me as an indictment of the way capitalism flattens the imagination, and proof that I need Hoffmann’s deep seas to dream in.

All speculative fiction challenges the established order, revealing the laws and norms we take for granted to be just one of an infinite array of possible arrangements. “What if?” ask Le Guin and Butler, and what seems to be given in our world dissolves. Atlantis, in “The Golden Pot” as in other Romantic literature, is a radically free world where a synthesis is possible between reason and passion, art and science, sight and insight, spirit and nature. Such utopias can strike the jaded adult reader as escapes from reality instead of encounters with possibility. But as the sociologist Avery Gordon has written, “We need to imagine living elsewhere before we can live there.”

*

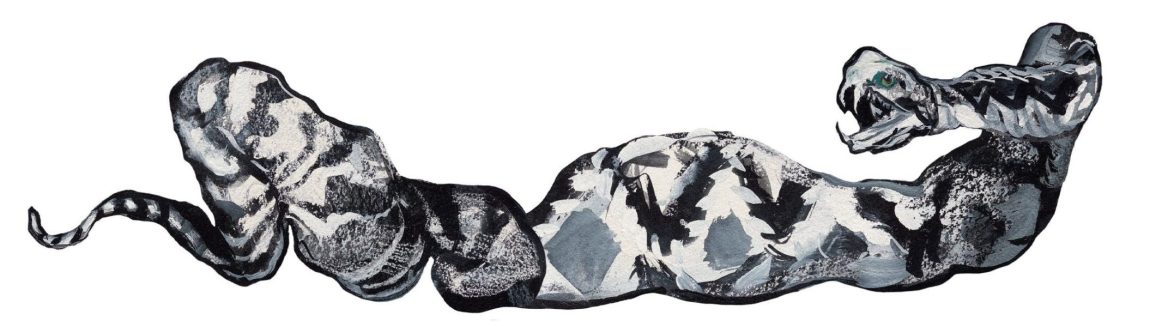

When I was four or five I froze on the stairs that led down to our backyard. A large oil slick of a snake was sunning itself on the middle step. My parents were seated within earshot but out of sight, chatting under a beige patio umbrella that felt suddenly a thousand miles from where the snake and I were regarding each other. I wondered what it saw. I thought I could probably jump over it, but the snake began moving in unpredictable ways, changing size and hue, tasting the air very close to my bare toes. Its body shivered from green to black to silver. I called for my parents, who told me not to be silly. They believed (not without reason) that the snake lived in my imagination, present to me but invisible to everybody else. “Come on down! There is no snake!” But I was hypnotized, watching a limbless dragon contracting on the redbrick middle step. Everything was honey-slow and hibiscus-bright—it was a summery sort of dread, this being Miami. I didn’t so much hold my ground as surrender to my terror. Eventually, my dad came to check on me, and I watched his irritation melt into awed surprise: “Damn, Jan. She was telling the truth. There is a snake up here…”

When I read Hoffmann’s tales, I am transported back to that threshold on the stairs. They return me to that rapt state that swings pendulously between belief and disbelief, terror and wonder. What will happen if I take the next step? Will the snake strike, or sing, or disappear? What is possible? What is true? “Do make an effort to recognize the well-known forms that hover around you even in ordinary life,” advises the narrator of “The Golden Pot.” “You will then find that this glorious kingdom lies much closer than you ever supposed.”

I’m a mother myself now, with a three-year-old daughter and a six-year-old son who spend most of their daylight in a land of make-believe. This can get exasperating at four in the morning when I am on Nightmare Patrol in our house, checking their closets for monsters and ghosts. I am sure I’d have my parents’ exact reaction to the green snake. Who wants to get up in hundred-degree Floridian heat to fact-check a kid’s delusion? Yet this story has had a surprising longevity in the memory of our family. My dad is particularly troubled by it; he loves to retell it. He is a kind and sensitive man—a wounded storyteller, like Hoffmann—and to this day he still apologizes to me: “You were right. There really was a snake.” The years pass and its meaning goes on shifting. Sometimes it shrinks into a common garter snake; at other times it dilates into something larger, something marvelously unfixed, the name of which we still don’t know.