The death of Nobel laureate Toni Morrison in the summer of 2019 loosed a flood of words upon the world. Elegies from artists and readers streamed down social media feeds; obituaries from critics and friends pooled in the usual venues. The New Yorker—which published her fiction exactly once in her lifetime—collected crystalline musings from Hilton Als, who admitted he had insulted Morrison, and Doreen St. Félix, who admitted she had feared her. The New York Times—with that familiar air of Isn’t she just so articulate?—ran an assessment from Harold Bloom: “Ms. Morrison began as a disciple both of Virginia Woolf and William Faulkner. She absorbed them splendidly in Song of Solomon, which seems likely to be a permanent work.” Why yes, it does. Wading around in all this eulogizing, I remember thinking that the only words I wanted to read were hers.

Vintage UK published new editions of her fiction, with introductions by Zadie Smith, Marlon James, and me, among others. Galleries showed artwork inspired by her books. USPS issued a Forever stamp. An edition of her quotations and a book called The Toni Morrison Book Club appeared, as if she were an inspiration board or a grandmotherly griot. As the novelist A. J. Verdelle writes in Miss Chloe, a memoir whose title refers to Morrison’s birth name, “Now that she’s gone, she’s a literary monument.”

Princeton University, where Morrison taught for seventeen years and where the building that now houses the African American Studies department was renamed for her, joined all this memorializing with an exhibit from her archives. “Toni Morrison: Sites of Memory” was on view at the Firestone Library’s Milberg Gallery this spring. I took the bus from New York to Princeton to see it on its last day, in early June. It felt like a fittingly belated pilgrimage: gazing out at the cemetery whose monuments always seem to mock the skyline of the city behind it; typing notes into my phone because I’d forgotten to bring a pen; making my way through the university’s postmodern pastiche of suburban kitsch, Collegiate Gothic, and uncannily green greenery.

The campus was summer-hushed; the library mostly empty; the exhibition space, an exhibition space: small and dark and spotlit, carved into a labyrinth of glass-cased artifacts, framed documents hanging on walls decorated with graphics of ink on paper—Morrison’s handwriting, I guessed. Her words were definitely echoing off those walls. They were screening a two-hour edit of an eight-hour interview with her conducted by Sigmund Koch for the Aesthetics Research Center at Boston University just after she published her masterwork, Beloved. It included a cameo from the renowned critic Hortense Spillers praising Morrison for capturing “the intramural life of black people.” I could hear Morrison’s smoker’s voice over my shoulder as I walked around, telling tales that made me chuckle, confirming certain notions I had, like how in the poetic section in the middle of that novel the words “Beloved” and “mine” seem to “hold those soliloquies” like “little hands.”

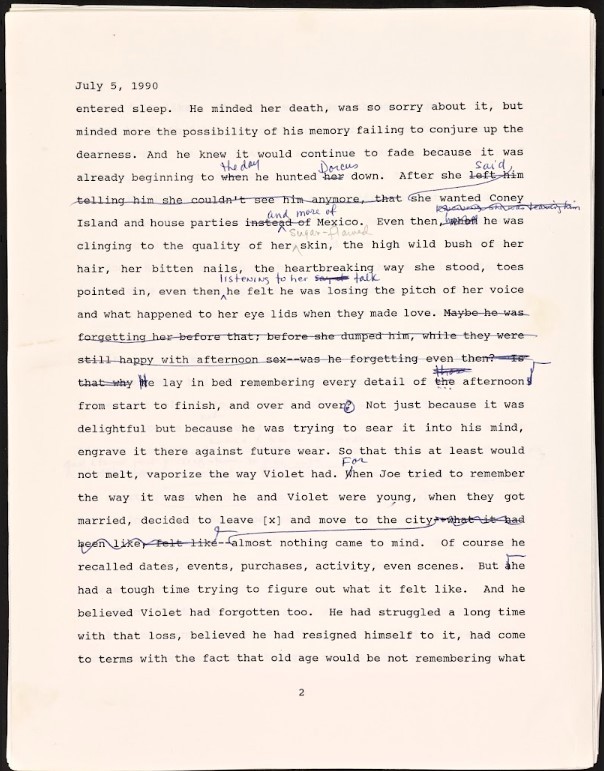

Many of the framed documents had burnt edges, lending a romantic air to misfortune. A fire at her home in Hudson, New York, in 1993 devoured much of the material surrounding Morrison’s early novels: notes, outlines, letters, diagrams. The curators of the exhibit, led by Autumn Womack, an associate professor of English and African American Studies, were blessed with the kind of discovery archivists dream of: Morrison had also scribbled notes in the margins of her day planners, some of which had survived the flames. One placard read: “Scorched and delicate, these pages reveal the tension between the presumed stability of an archival object and its fragility.”

An exhibit of archival materials is about as close to putting an author in a museum as you can get. It sits somewhere between, say, a tour of the writer’s home—which feels akin to celebrity worship—and an exploration of the writer’s words, which feels like the scholar’s remit. At what level should the curation be pitched? How biographical should the placards be, how academic? The question that hovers over all literary tourism of this kind is: Who is this for?

*

This question intensifies when it comes to Toni Morrison. As the exhibit demonstrated in a section called “Beginnings,” Morrison was an archetypal writer: she was on the staff of her high school newspaper; she acted in Shakespearean plays at Howard University; she experimented with pen names (Should she go by Chloe, her given name, or Toni, a shortening of her baptismal name, Anthony?); she wrote insecure letters to editors about whether The Bluest Eye was a real novel. What the exhibit never quite manages to capture is that Morrison was truly exceptional, too—a black woman born in 1931 who didn’t go just to college (already a rarity) but also to graduate school at Cornell in 1955, where she wrote a master’s thesis on Faulkner and Woolf, both of whom had only recently become canonical. Morrison is still one of the only black editors to dot the snowy landscape of publishing; after she left Random House in 1983, the number of black authors published there dropped precipitously.

Advertisement

Despite the seemingly widespread availability of artifacts of Morrison’s public persona—including a charming, jumbly documentary, The Pieces I Am (2019)—one cannot assume that the average American knows anything of her singular life. This is the biographical conundrum. When it comes to the writing, the question of audience gets even more complicated. Her novels are by now classic works of American literature that can be considered in the context of their making and reception: When, how, and with what influences and responses? But the books are difficult, and they aren’t well known enough for her materials to be exhibited without substantial supporting analysis.

The exhibit gamely negotiated these difficulties by working on two levels, informing the intrigued while gifting the informed with hidden Easter eggs. For instance, it presented the first and last page of an early unpublished short story, “Gia,” to signal the start of her literary career but also to titillate those of us who thought she’d written only one short story, “Recitatif.” Yet I, for one, was more struck by the realization—which the exhibit didn’t seem to note, and which I probably shared with only a handful of other visitors—that a line in “Gia,” about a nail driving its way up through a foot, eventually became an origin story for Pecola’s mother in The Bluest Eye.

Who is this for? Me. I was in a Morrisonian paradise. I felt abrim with recognition. I laughed happily at an outline for Song of Solomon:

III. Phosphorescent sheen = like money = Macon

IV. Dry skin like the hulls of pecans

V. Odor

VI. “Pearls”

It was so idiosyncratic that it suggested a new definition of literary genius as a collocation of category errors. Barred for some reason from taking pictures, I tapped manically at my phone, transcribing selections of Morrison’s essayistic notes about what she called “bookvoice” in Jazz: “How does a book sound when it is speaking as itself and taking the prerogative of being both a voice, the narrator’s voice, and the voice of a talking book?”

I changed my mind about some things. I adjusted my quibble with how she depicts Native Americans when I saw her research question for A Mercy: “When did Indians start calling themselves ‘Indian’?” My understanding of the importance of a minor character, Stamp Paid, deepened as I read her scrawled notes describing Beloved as a “dance” between him and Baby Suggs, Ella, and Paul D, respectively, and specifically counterposing him (“Exterior/ Stamp = news of the world/ Moral war/ Community obligations to the weakest link”) to the novel’s heroine (“Interior/ Sethe = Retreat into fantasy/invention/ Closing out the world/ Reject what rejects her”).

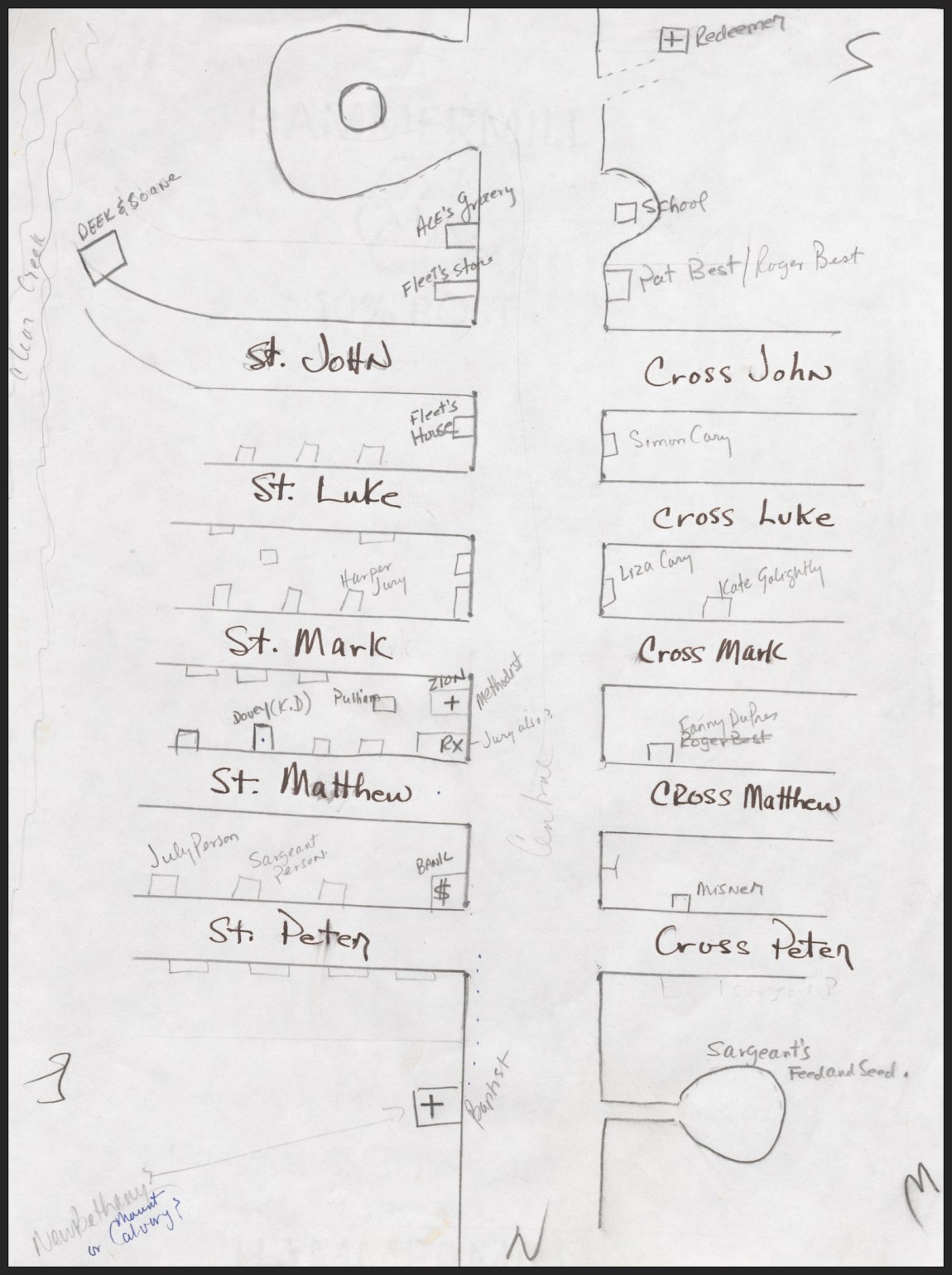

There were more radical epiphanies as well. While I knew Morrison had initially planned for Beloved to reach beyond the nineteenth century, I thought she had simply connected the bloodlines of its characters to those in Jazz (1992)—Beloved running pregnant and naked off the page of one novel and onto the page of the next, where she is renamed Wild and gives birth to the hero, Joe Trace. Now, in the last section of the exhibit, with the modish but somewhat deceptive title “Speculative Futures,” I saw a sketch of a family tree with alternative lineages—a different putative child of Beloved and Paul D named Susannah. I read a detailed outline in which “the ghost” Beloved would age slower than other people and thus be able to reappear as a maid in a household in the Eighties (!). Morrison never completed this tripartite project, perhaps because she could not sustain this more whimsical conceit of a ghost or “haint” as she immersed herself in the history of slavery’s brutalities for its first volume.

I also learned the answer to a question that had long puzzled me. Morrison writes in an essay, “Home,” a draft of which was on view as “The Last Word,” about struggling with regret over changing something in the final lines of Beloved at the request of her editor, the late Robert Gottlieb. She vacillates about whether she or he was right, but she never says what she changed. The exhibit displayed three manuscript versions of the novel’s last page, with a few final revisions. In one version, the last two words in the phrase “no clamor for the join” are circled with a question, presumably from Gottlieb: “Is there a less eccentric phrase you can substitute?” This query has been peremptorily crossed out. But the words in question have been changed to “a kiss.” In the final version, which corresponds to the published text, “no clamor for the join” has become “no clamor for a kiss.” The join! The shining revelation of this abandoned word, which, like “cleave,” means both separation and union (as in a join of wood), lit up a constellation of insights for me.

Advertisement

And yet I wondered—I wonder now as I write this—how exciting these sparkling treasures of the archive would be for someone who doesn’t know Morrison’s oeuvre in detail. I dutifully took my place in the group tour to pretend to be this kind of blank slate. But as soon as the docent, a respectable young person, likely a student, started reading out from a sheet of paper what sounded like the same words printed on the placards, I wandered off again. The questions from the tour that I overheard as they passed by me suggested a curiosity that couldn’t quite be satisfied. (“What is a tar baby?” “The title of one of Morrison’s novels.”)

The exhibit was, in a word, tantalizing. It raised an irresolvable question: What do we seek in the remnants that writers leave behind? You can watch the author Edwidge Danticat’s lovely, light keynote for the symposium that launched “Sites of Memory”; the range of her concerns there and in the Q&A afterward suggests the same tension. Neither a museum nor an archive, this exhibition was essentially the mounting of a monument, a kind of memorial. And as the toppling of even the grandest looking ones over the last few years has shown, the foundations of monuments are far more unstable, our feelings about them far more fickle, and the meanings we find in them far more fluid than their sturdy appearance would suggest.

*

Now, Toni Morrison was not averse to monuments. First of all, she was a diva. She knew the worth of her work and was unembarrassed to be honored for it. Second of all, she respected art and history, even—perhaps especially—their gravest distortions and atrocities. I heard from a friend that during the Q&A after Princeton’s ribbon cutting in 2017 for the newly anointed Morrison Hall, someone asked her how she felt about the recent fervor in America for tearing down Confederate statues. “I don’t believe in erasure,” came the reply in, I imagine, that throaty, wry voice of hers.

On this point, Morrison was consistent. In 1974 she published The Black Book, a compendium of historical fragments of black life—some, powerful testaments to cultural and literal survival; others, like Amos ‘n’ Andy, embarrassing stereotypes. She wrote an essay about the book that begins:

In 1963, when the N.A.A.C.P. secured the old Morrison Hotel in Chicago for its annual national convention, one of that organization’s demands was the removal of two statuettes of black jockeys standing in the lobby. The hotel management reluctantly agreed, but before the statuettes could be temporarily removed, they were draped with sheets. Their eyes were veiled, the jaunty caps were shrouded, those sassy hip-twists hidden. No longer would those baleful faces offend the sensibilities of blacks or encourage the contempt of whites…. In that absolute fit of reacting to white values, we may very well have removed the patient’s heart in order to improve his complexion.

Morrison’s words in 2017 about “Morrison Hall” and in 1974 about the “old Morrison hotel” (no relation) might seem counterintuitive. Rather than leaping to right wrongs, she warns us instead about our persistent tendency to “confuse dignity with prettiness, and presence with image.”

In the essay “The Site of Memory,” from which the Princeton exhibit takes its title, she writes of the history of this sentimental concealment in slave narratives:

Over and over, the writers pull the narrative up short with a phrase such as, “But let us drop a veil over these proceedings too terrible to relate.” In shaping the experience to make it palatable to those who were in a position to alleviate it, they were silent about many things, and they “forgot” many other things.

I fear that in the rush to monumentalize Morrison, to make her a palatable icon of black wisdom or black joy or black excellence, we may inadvertently veil—even shroud—her with beatifying (or burnt-edged) sheets.

But to tear down a monumental figure or to prettify it are not our only options. Morrison’s own work is instructive in this regard. She had a hard-won sense of how we ought to attend to cultural artifacts, whether they were what she called “dark valleys of unraised consciousness” like those black jockeys and the raucously racist Amos ‘n’ Andy, or the canonical works of art and literature that inspire and disgust us. Much of her criticism—and some of her fiction as well—was aimed at uncovering the roiling, sometimes disturbing forces underlying the creation of art. In the Tanner Lectures she delivered at the University of Michigan in 1988, she spoke of what she called “the Africanist presence” at the heart of white American literature, a “ghost in the machine” that made it go, that made it function—even as it relied upon the racist logic of a grotesquely dehumanizing and objectifying violence.

Morrison didn’t want to erase this art, she wanted to know how it worked; she was interested in what the image of “serviceable” black bodies enabled for those white writers, and why. So careful, so intelligent was she that even her sharpest critique bestowed dignity on its object. I would describe her sensibility as a combination of grace and acuity, as the highest form of discernment, as what black people first named shade, which, as Dorian Corey says, is not just a “vicious slur fight” but rather when your reading goes “to the fine point.” Take Morrison’s equanimity about the blatant racism in an Ernest Hemingway novel: “an author is not personally accountable for the acts of his fictive creatures, although he is responsible for them.” Or her plainly accurate description of Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn in her introduction to a new edition as “this amazing, troubling book.”

Morrison teaches you to read this way—even to read her this way. I found myself catching “amazing, troubling” glimpses of her art in “Sites of Memory,” as if sighting a spectral Morrisonian presence in Princeton’s stately monument. It has always seemed to me, for example, that The Bluest Eye is in conversation with Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita. Without flinching, Morrison, too, depicts both the sexual pleasure of a man raping his child (“The tightness of her vagina was more than he could bear”), and the discomfiting possibility of that child’s emotional complicity in that rape. Morrison’s notes about the novel in the exhibit confirm this: “Cholly’s advances were repulsive to her only on the one hand; on the other, they were human attention, however bizarre, and therefore desirable to her”; “How + why he rapes her, + how she (in loneliness + with a yearning to touch somebody) seduces him the second time.” For obvious reasons, the curation does not draw our attention to these intentions, leaving them overshadowed by Morrison’s better-known claim that she wrote a book she wanted to read and by her poignant premise of a little black girl who wants blue eyes. Perhaps with the hope that her morally and aesthetically knotty art not “offend the sensibilities of blacks or encourage the contempt of whites,” the exhibit could not help but veil the words from Morrison it chose to display.

How do you mourn without worshipping a monument or desecrating it? There’s a scene in Sula I think about often. A black woman, looking for a place to relieve herself when her train pauses at a station with no bathrooms for “colored women,” stops short at the sight of “some white men…leaning on the railing in front of the stationhouse…their tongues curling around toothpicks.” She eventually learns to ignore “the men who stood like wrecked Dorics under the station roofs of those towns.” This is the Morrisonian slant par excellence. The white men’s gaze is gazed back at, dismissed, and wrought into a perfect simile. Consider the curt rhythm and palindromic rhyme of “wrecked Dorics”; how it reflects the knowledge, here of ancient architecture, a black woman is presumed not to possess; how those intimidating white columns are wrecked yet persist in a regal image of their own undoing. How do you mourn a monument? You read it. You write it.

People love to quote Morrison on how there is no “suitable” memorial of slavery, not even a “small bench by the road.” (The Toni Morrison Society has now made twenty benches, which is impressive but maybe misses the point.) I prefer to quote the original “Site of Memory,” Morrison’s wonderfully strange essay on the relations between fiction and memoir, image and text, revelation and obscurity, and the obligations of art and of history. She mentions that, as an editor, she thought she “understood writers better than their most careful critics, because in examining the manuscript in each of its subsequent stages I knew the author’s process, how his or her mind worked, what was effortless, what took time, where the ‘solution’ to a problem came from.” But then she realized that there is something more mysterious about “how the act of imagination is bound up with memory”:

You know, they straightened out the Mississippi River in places, to make room for houses and livable acreage. Occasionally the river floods these places. “Floods” is the word they use, but in fact it is not flooding; it is remembering. Remembering where it used to be. All water has a perfect memory and is forever trying to get back to where it was. Writers are like that: remembering where we were, what valley we ran through, what the banks were like, the light that was there and the route back to our original place. It is emotional memory—what the nerves and the skin remember as well as how it appeared. And a rush of imagination is our “flooding.”

Many people will remember Toni Morrison for her museum-worthy life, for the career as an editor, teacher, and writer that Princeton has conscientiously archived and deftly curated. But I know that I will remember her for elaborate metaphors like this, for what her unaccountable rushes of imagination carved into our ground, for what spills into place and what floods in me, whenever I reread her.