My romance with history began in the fifth grade, in the 1960–1961 school year, in a class taught by the only male teacher in my West Virginia elementary school, Mr. McHenry. Our ancient history textbook had at most a few line drawings and no photographs at all that I recall, but it sucked me in with the indiscriminate force of my mother’s brand-new Electrolux vacuum cleaner. How ancient history made it into the curriculum of a fifth-grade class in a public school in the hills of West Virginia has long puzzled me. What I wouldn’t give to own a copy of that textbook! Its power to transport put Walt Disney’s “Fantasyland”—must-watch television every Sunday night—to shame.

History with a capital “H” began, Mr. McHenry explained, in the Fertile Crescent, God’s chosen site of fecundity nourished by the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers and the Mediterranean Sea—the first place on Earth, we read, for agriculture. Somehow settled farming led to hallmarks of human progress such as bricks, glass, and the wheel, and most spectacularly the novel form of memory called writing. These elements came together to make this region “the cradle of civilization.”

My dad, the youngest of seven sons, was born on our family farm in the Potomac River Valley in the Allegheny Mountains, on Patterson Creek, the fifty-mile tributary of the river’s North Branch. Living in this rich, verdant agricultural region, I couldn’t quite believe that glass and writing had emerged from the tending of crops. Trying to comprehend this chain of events demanded that I rethink my condescending attitude toward the 4-H kids, as we called them, some of whom had grown up on farms and were bused to the high school down in the county seat. My friends and I mercilessly mocked them as “country,” although we’d later learn that everybody else in America, thanks to LBJ’s war on poverty, were mocking us paper mill town–dwellers as “country,” too.

From there we plunged into cuneiform writing and the presumption of innocence inscribed in the Code of Hammurabi; then we skipped from the eighteenth century BC to Nebuchadnezzar the Great twelve hundred years later, and the luxurious Hanging Gardens of Babylon that he reportedly built for his beloved wife. Next we landed on Xerxes, the son of Darius the Great, and his dastardly invasion of Greece in 480 BC, to which all of this fascinating detail about crops, animal husbandry, bricks, glass, the wheel, and writing turned out to be preliminary. It was a mere preamble to Greece’s Golden Age.

That may have been the most exciting class I ever took. But I didn’t pay history much mind, academically, raised as I was to be a doctor. I would have been premed at Yale, had Yale a premed track. I arrived in New Haven in September 1969, the same month that the university’s program in Afro-American Studies opened its doors, but my father had admonished me, just before I left home, not even to think about majoring: “Your ass has been black for eighteen years and I am not paying for that,” was the last thing I remember him telling me as I climbed into my new car and headed off for the long, lonely drive up I-95. But I did enroll in one of Yale’s first lectures in Afro-American history, a two-semester course taught by William McFeely. (He was the second person to teach the course, Eugene Genovese having left Yale just as I arrived.) It changed my life.

Introduction to Afro-American History was one of the largest lecture courses in the history department, and I think the most popular course among my Black classmates. Thanks to newly implemented affirmative action admissions policies, a cohort of ninety-six Black freshmen and transfers arrived on campus at the same time, including such future notables as Congresswoman Sheila Jackson Lee, the Stanford education innovator Linda Darling-Hammond, the neurosurgeon and housing and urban development secretary Ben Carson, the Pulitzer Prize–winning composer Anthony Davis, the AME bishop Frank Reid, and a host of other kids who would go on to integrate law firms, medical faculties, and Wall Street. I met many of them for the first time in Mr. McFeely’s class (the fashion of professorial address at Yale back in the day).

Like so many other African Americans in the Sixties, I had been introduced to Black history through Ebony magazine, delightfully required reading in our household—the race’s very own “dream book.” Lerone Bennett Jr. had a column on contemporary Black politics in which he explained the goals of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and Black Power. Even more riveting to me was his series “Pioneers in Protest,” twelve essays that introduced the lives and careers of important figures, white and Black, in African American history—among them Prince Hall from the Revolutionary era, John Brown, Frederick Douglass, Harriet Tubman, Sojourner Truth, the Black nationalist Henry Highland Garnet, and, finally, W. E. B. Du Bois.

Advertisement

Ebony’s genius was to intersperse these stories with spreads of the grand funerals of cultural figures like Dinah Washington and photos of models in stunning outfits traveling in the Ebony Fashion Fair, effectively juxtaposing the glories of a shared Black past with the triumphs of our present, particularly material ones. A December 1964 cover story on Sammy Davis Jr. featured his “mansion” in the Hollywood Hills, his Rolls Royce, his white wife, Mai Britt, and two handsome children—three years before Loving v. Virginia legalized interracial marriage throughout the country.

Bennett’s columns, taken together, constituted an introductory college course on Black history, and I even had the audacity to send him a letter encouraging him to collect “Pioneers in Protest” into a sequel to his pathbreaking book Before the Mayflower (1962), which he did in 1968, no doubt without my prompting. But McFeely’s class was my first deep dive. In Black history lay buried the stories of ancient Africa, the mysteries of our existence in this strange, new world, and the extraordinary, inspiring tales of great African American women and men, the knowledge of whose existence had been denied us.

Why was our history so important to us? Because we had been told that we had none. Just six years before we arrived in New Haven, the historian Hugh Trevor-Roper claimed that “there is only the history of the Europeans in Africa. The rest is largely darkness.” In his view, history was “essentially a form of movement, and purposive movement,” which Black Africans simply did not have, an idea that echoed throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries after it found endorsement in Hegel’s posthumously published Lectures on the Philosophy of History. By extension, in the racist scheme of things, what applied to Africans applied to us.

In one of his first lectures, Professor McFeely underscored what was at stake in the teaching of our history by quoting Arthur A. Schomburg: “The American Negro must remake his past in order to make his future…. History must restore what slavery took away.” Then he quoted Carter G. Woodson’s dictum that “if a race has no history, if it has no worthwhile tradition, it becomes a negligible factor in the thought of the world, and it stands in danger of being exterminated.” Our generation, the affirmative action generation, the largest class of Black students in Yale’s history, had been issued a call to arms; in studying Black history we were on a mission, and we threw ourselves into the task of restoring what Woodson called “the accounts of the successful strivings of Negroes for enlightenment under most adverse circumstances,” which “read like beautiful romances of a people in an heroic age.”

Du Bois wrote that “the Negro has long been the clown of history; the football of anthropology; and the slave of industry.” By mastering the hidden facts of the Black experience just a year and a half after Dr. King’s murder, as so much about American race relations was changing, we were charting the path of our people’s future. We could have no idea at that time how much we were part of these changes nor how much more was about to change. The initial cohort of Yale’s experiment in affirmative action hit New Haven—and Mr. McFeely’s class—at the high-water mark of Black radicalism. Black Panther Party members greeted us on our arrival in New Haven, which had become the center of the Party’s attention after nine of its members—including its cofounder, Bobby Seale, and the leader of its local branch, Ericka Huggins—were indicted there. The school year would culminate with a campus-wide moratorium on classes and May Day rally, both in support of the Panthers on trial and in protest of the Vietnam War.

Our textbook, which quickly became the staple of introductory Black history courses throughout the academy, was From Slavery to Freedom: A History of Negro Americans, by John Hope Franklin—the precious third edition paperback with its black and white cover, published in that annus mirabilis, 1969.

*

I should have begun to realize that I was never going to end up a doctor as I loaded my backpack with everything I thought I would need on the gap year I took as part of Yale’s innovative five-year BA program. After the tumultuous political events on campus during my sophomore year, I felt that I not only needed a break but needed to spend time in Africa, about which I had heard so very much in the seemingly endless debates that occupied quite a lot of our time on campus. I spent it in Tanzania, working in an Anglican Mission hospital in Kilimatinde, a poor, tiny village about four hours by Land Rover from the nation’s capital, Dodoma. Today Kilimatinde’s population is about six thousand; it was closer to a thousand during the four months I lived there. There was no running water for the villagers and no electricity; we lighted our way around at night with kerosene lanterns. Most Tanzanians lived in homes made of mud with thatched roofs. Never had I been so far from home. It took six weeks for an aerogram to reach the States; a telegram shaved it down to a week.

Advertisement

My job at the 120-bed hospital was, basically, to hold a mask on the face of anesthetized surgical patients to keep them sedated. My qualification? I spoke English and could follow instructions. I witnessed a wide range of procedures, including the removal of a soccer ball–sized tumor from a woman who complained that she had been pregnant for two years, the repairs of limbs wounded by rabid hyenas, and the treatment of burns with maggots (an effective way to clear infected tissue, as was explained to me). I most remember two burn victims, both children. The baby had been strapped to his older brother’s back while his parents went deep into the bush to find more firewood. Losing his balance because of the baby’s weight, Sebastian tumbled into the fire. Both died, the baby first, his brother a couple of days later, just seconds after our doctor and I had examined his bandages. Despite the dozens of desperate surgeries I witnessed, that was the only time I saw a person die.

I became intrigued by the power relations between the Australian missionaries with whom I was living and working and the Tanzanians God had sent them to “save.” Most of present-day Tanzania had been part of German East Africa from 1891 to 1919. My bedroom was in a former German prison; a small German cemetery lay a few hundred yards behind. The missionaries had access to a borehole the Germans had dug as their water supply; the villagers, on the other hand, had to fetch their fresh water about a mile away. So many of the diseases we treated, such as bilharzia, were related to lack of access to fresh water—why not share the well?

When the hospital got a new grant, its only doctor, an Australian missionary, wanted to use it to build a new wing. I argued as passionately as I could for using the money instead to extend pipes down the escarpment to give the villagers the same water access that we had. But what did I know? I was young and brash and saw myself as the advocate for the Tanzanians. I had arrived in the village proudly wearing my Afro, which lasted about a week in the equatorial heat before I had it cut off. (My Australian colleagues gleefully pointed out that not a single African was wearing this style that, they snidely implied, had been invented in the States.) I lost the argument.

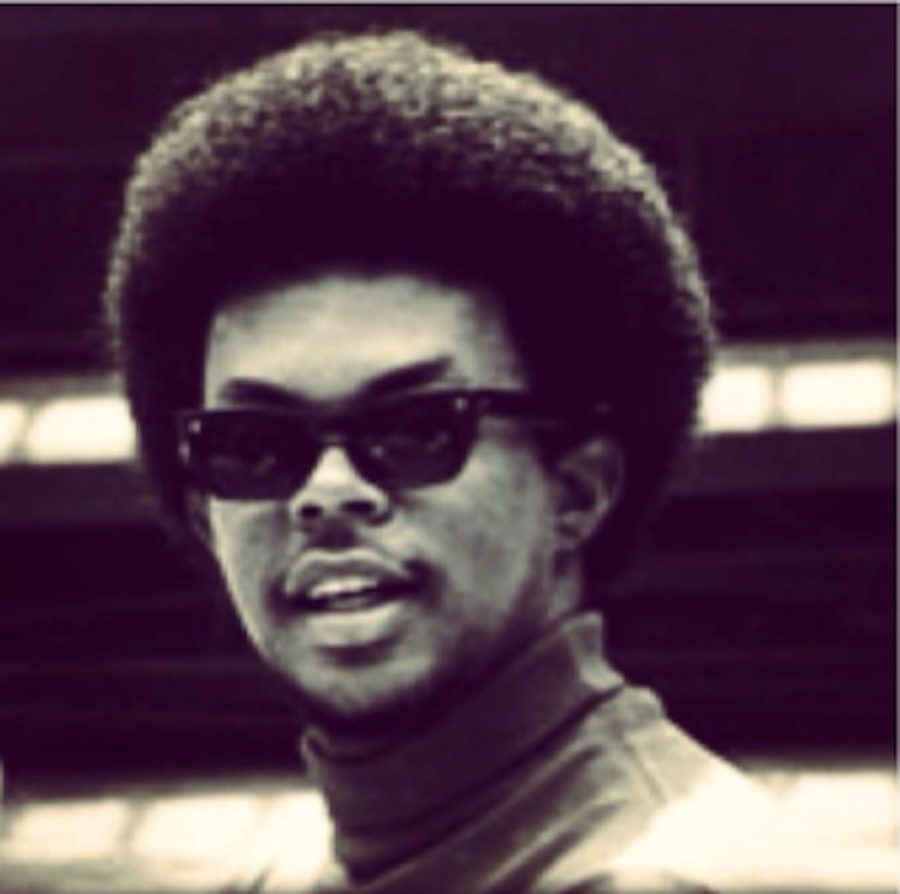

I left the village for good and headed to Dar es Salaam, the famous seaport and veritable center of African–Arab hybridity along the Swahili coast, where one of Africa’s great universities at that time was located. The famous radical historian Walter Rodney was teaching there. Hearing him lecture at a conference about “how Europe underdeveloped Africa” two years before he published his book of the same name—and nine years before he was assassinated in his native Guyana—might have helped push me toward history as a major when I returned to Yale. It was dazzling to see a professor wearing a daishiki and a neatly trimmed Afro, imported, I suppose, from his years as a graduate student in London.

On an overnight dhow trip from Dar to Zanzibar I met a recent Harvard graduate named Lawrence Biddle Weeks, now an Episcopal priest. He had been fantasizing about traveling “from Cape to Cairo,” following the route of the railroad Cecil Rhodes had imagined connecting Africa from south to north. My own fantasy was to hitchhike across the equator, an idea that had intrigued me since elementary school, when I read a Reader’s Digest article about an African boy who miraculously did just that. We flipped a coin to see which fantasy it would be. Mine won.

Michelin map in hand, off we went, hitchhiking from Dar to Mombasa, Mombasa to Nairobi, Nairobi to Kampala, Kampala to Kigali, Kigali to Goma on Lake Kivu, then a six-day trip through the rough terrain of eastern Congo to catch the riverboat for the famous ride down the Congo River from Kisangani to Kinshasa, just 320 miles from the Atlantic Ocean. I had taken four books with me when I left New Haven: Don Quixote, Moby-Dick, From Slavery to Freedom, and Arthur Frommer’s Europe on Five Dollars a Day. (“Most Europeans don’t regard a bath or shower as a daily necessity. They normally get by with the vigorous application of water from a sink, and save the full-scale scrubbing for a bigger, and normally, weekly event.”) But the demands of the hospital had not allowed for much downtime, and only on my slow trek across the equator did I finally devour them cover to cover.

From Kinshasa I flew to Ghana via Lagos on a pilgrimage: to pay my respects at the grave of just about every Black student’s hero at that time, W. E. B. Du Bois, who was then interred at Christiansborg Castle in Osu, before his remains were removed to his own mausoleum in Accra, where he’d lived in his last years. When I left New Haven I was embarking on my own “return to the motherland,” my own Roots. It had never occurred to me that I would find myself standing in front of the Door of No Return at Ghana’s Elmina Castle, the door with only one doorknob, the door that swings only one way, from Life to Death.

*

On returning home I realized that I was as interested in writing about these experiences as I was in living them, if not more so. I proudly became a history major under the tutelage of John Morton Blum, whose evocative, masterfully crafted lectures twice a week in his popular course Politics and Culture in Twentieth Century America remain my models of pedagogy. Mr. Blum delivered them from yellow legal pages, which he read verbatim. But he read them in a way that brought the people and events he was describing vividly to life, each lecture somehow a miniplay, a scene in the larger drama of the relation of politics and economics in the reshaping of class and race over the course of the twentieth century, from the Republican Roosevelt (the title of one of Mr. Blum’s best-known books) through Hoover’s financial blunders, the onset of the Great Depression, Roosevelt’s New Deal spending, and the enormous expenditures for the war. It was clear that for Mr. Blum it was all about the Benjamins, as we say; at base, economic relations made the world go round—a startling revelation to a student who had seen so much of the world through race-tinted glasses.

My Yale dorm was Calhoun College, named for John C. Calhoun, the South Carolina senator who staunchly defended slavery. (That irony was not lost on the affirmative action generation, but it never once occurred to us to demand that the name be changed, as Yale students did eight years ago, and we were not shy about making demands. As the college’s first Black master, Charles T. Davis, liked to say, it was a greater victory to take over the master’s house than to burn it down.) Over meals in the Calhoun dining hall I regaled my friends with stories of my year abroad. By then a couple of them were editing The Yale Daily News, and one encouraged me to submit an essay about my travels. The day it was published happened to be a day on which Blum’s class met. “Is Mr. Gates in class today?” he asked as he stepped to the podium. I looked around nervously to see if I was the Mr. Gates about whom he was speaking. When no one else stood, I did. “Nice column in today’s paper,” he said, before turning to the day’s lecture. At that moment, a woman whose attention I had been trying to attract, with absolutely no luck, turned to me and smiled. That night I wrote my second column.

Mr. Blum told me that he thought that I should be a writer, either as a professional historian or as a journalist. Wasn’t there a qualitative difference between the two, I asked? Not at the highest levels, he said. He mentioned E. J. Kahn Jr., who wrote for The New Yorker (and whom I had bumped into coming out of the door of the US Information Agency library in Dar es Salaam), and Anthony Lewis, who wrote for The New York Times. Blum encouraged me to pursue graduate work at Oxford or Cambridge. Getting elected to Phi Beta Kappa at the end of my junior year and earning my history degree summa cum laude were my ways of trying to make this great scholar proud. Mr. Blum even managed to secure me a literary agent before I graduated.

I got a Paul Mellon Fellowship to study for two years at Cambridge and spent the summer writing for Time magazine in London. Once or twice that summer it crossed my mind that I might enjoy a career in journalism, but I dismissed those thoughts as soon as they arose. As what I still imagined would be an interlude before returning to medicine, I chose to pursue a graduate degree in English literature. What were the odds that I would end up living in Clare College as one of only three Black students—and that one of them had also come to Cambridge to be a doctor, and then thought better of it? What were the odds that a great African writer would have found safety there, in exile from the tyranny that had overtaken his native country? They were Kwame Anthony Appiah and Wole Soyinka—godfathers to my daughters and lifelong friends to this day. One night, over Indian food and lots of good wine, they gave it to me straight: you are never, ever going to become a medical doctor. If I didn’t cry, it was only through an enormous effort to keep my composure in front of these regal African friends.

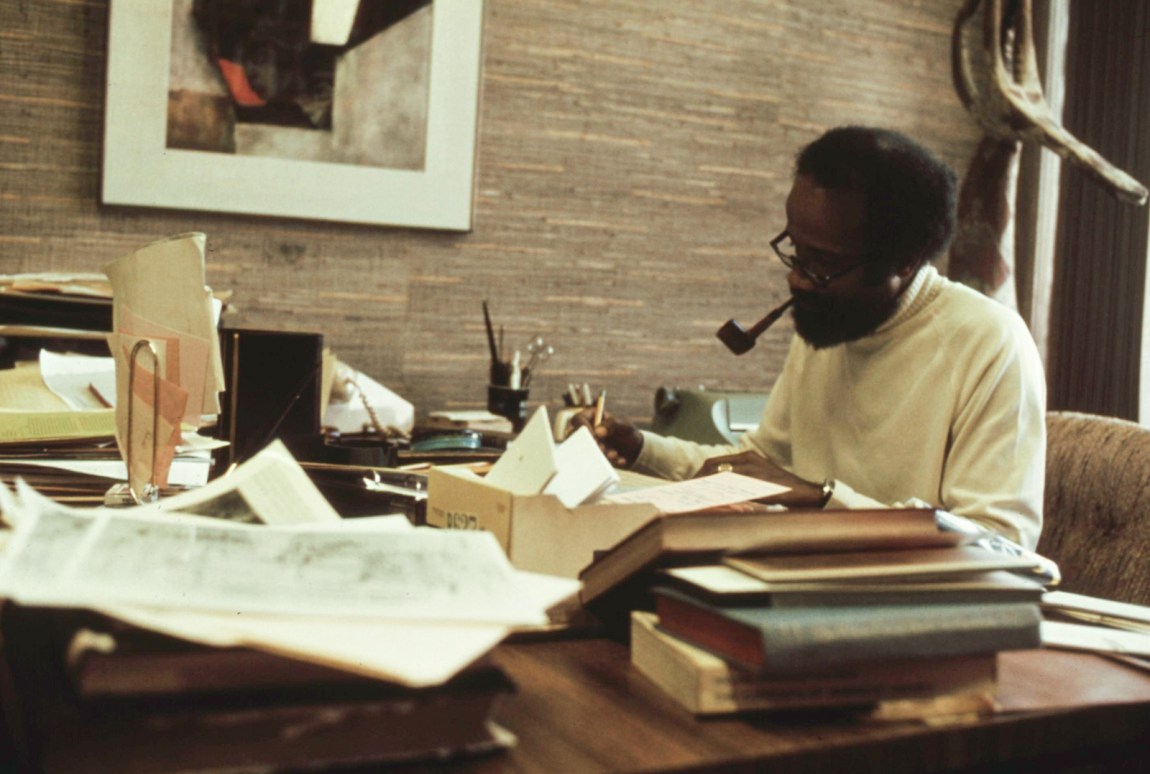

The challenge at Cambridge, once I had made my way into the Ph.D. program there, was how to turn my love of Black literature into a study. “Tell me, sir,” my tutor once asked me, “What is ‘black literature’?” I bridled. Then I began to search for intelligent ways to answer his question, an intriguing one, I realized. Gradually I began to notice that texts by Black authors, though thoroughly grounded in and responsive to works in the standard literary canon, had a peculiar way of responding to each other, of repeating and revising scenes of instruction, metaphors, tropes, themes taken from deep within African American vernacular culture. It enabled me to establish a sense of a Black literary lineage that was connected not by any mystical essence of “blackness” but by creators who were self-consciously in dialogue with one another, whether through contestation or complementarity.

*

Around this time I happened to stumble on a BBC documentary series called Civilisation, hosted by Sir Kenneth Clark. It was, for me, an epiphany: an entirely new way of storytelling. Here was a way of delivering an essay, in effect, with all the bells and whistles of Disney’s “Fantasyland.” Not exactly “like history written with lightning,” as Woodrow Wilson is said to have described The Birth of a Nation, but close: oral history lessons delivered with the riveting force of Mr. Blum’s lectures but embedded in powerful visuals with musical accompaniment and the potential to reach millions of people. Soon, with equal avidity, I watched Jacob Bronowski’s 1973 BBC series The Ascent of Man. And when my Cambridge friend Jamie Galbraith invited me to his home to meet his father, John Kenneth Galbraith, he spent much of the afternoon sharing his pleasure at hosting his series, The Age of Uncertainty. I was captivated—and full of envy. Perhaps I should have studied film, I remember thinking. But that ship had sailed.

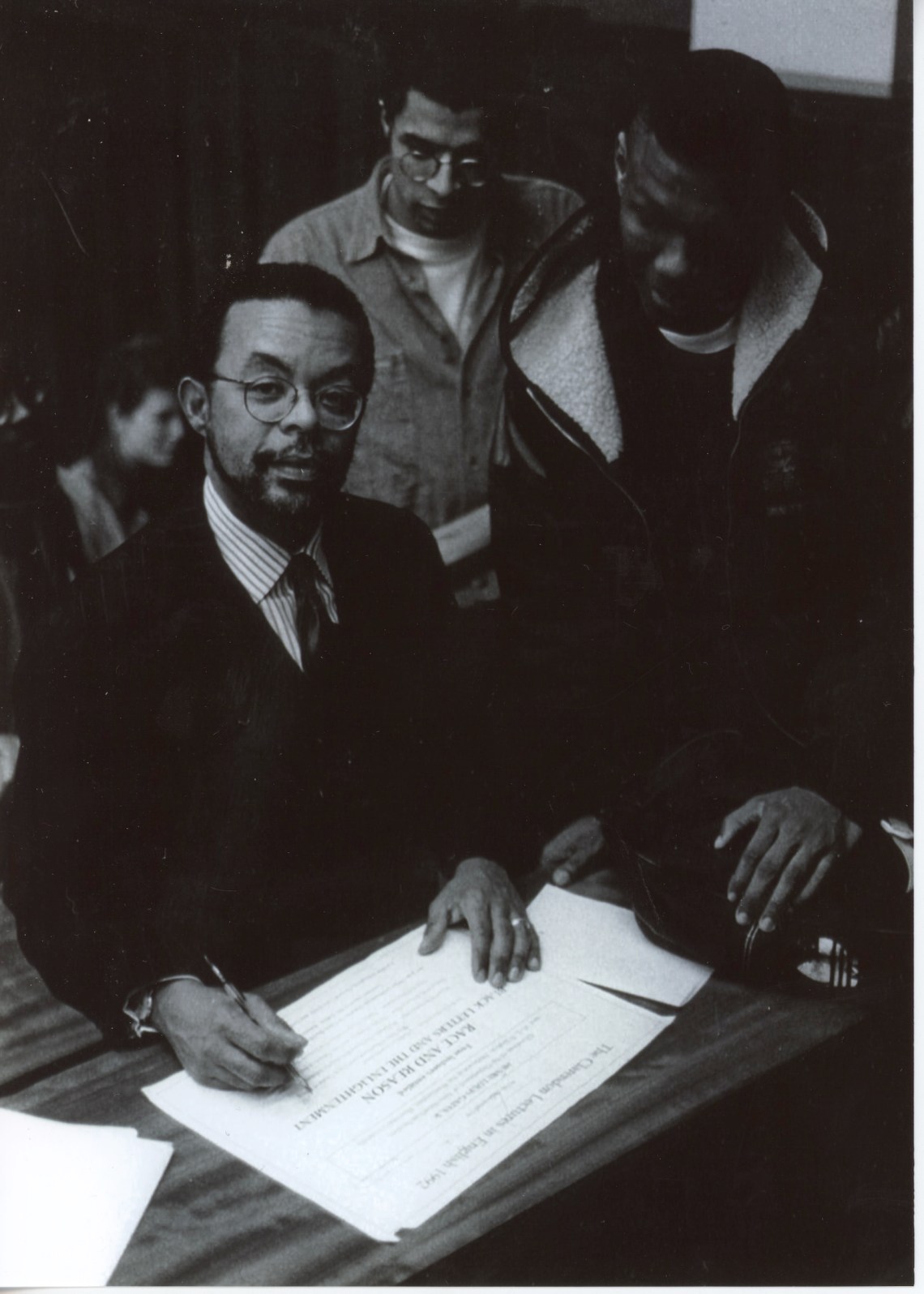

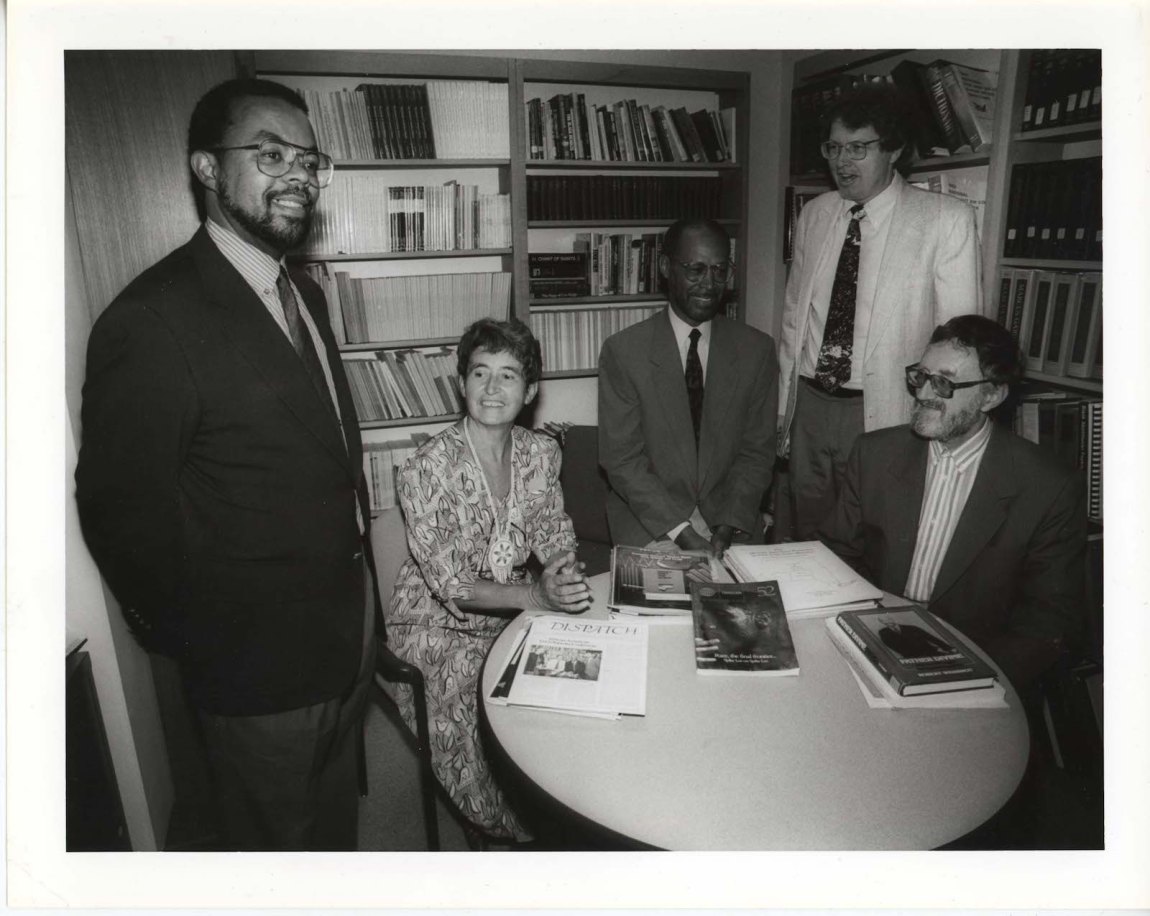

Or so I thought, until I came to Harvard in 1991 to help reboot their African American Studies department. Alberta Arthurs at the Rockefeller Foundation set up a meeting to introduce me to the filmmaker Henry Hampton, the most famous Black documentary filmmaker in history, the genius behind the Emmy-winning Eyes on the Prize. Visiting Henry’s studio, Blackside, Inc., in the South End, as he patiently walked me through the documentary filmmaking process, from conceiving the project to filming and gathering archival footage, and ultimately to editing something worthy of being aired on television, I found myself transported back into the wonder I felt studying ancient history in the fifth grade. At the end of the day I asked Henry if he had ever thought of using a professor in front of the camera, as they do in England. After a long pause, he looked me in the eye and said, “Yeah…that’s in England!” I left Blackside convinced that this English form of storytelling was in the cards neither for Black history nor for this Black studies scholar. I would keep the fantasy close to my chest, but I was inebriated by the wonders of creating narratives on film, haunted by the wide range of possibilities for Black storytelling, disappointed that experimenting with those possibilities would not be my fate.

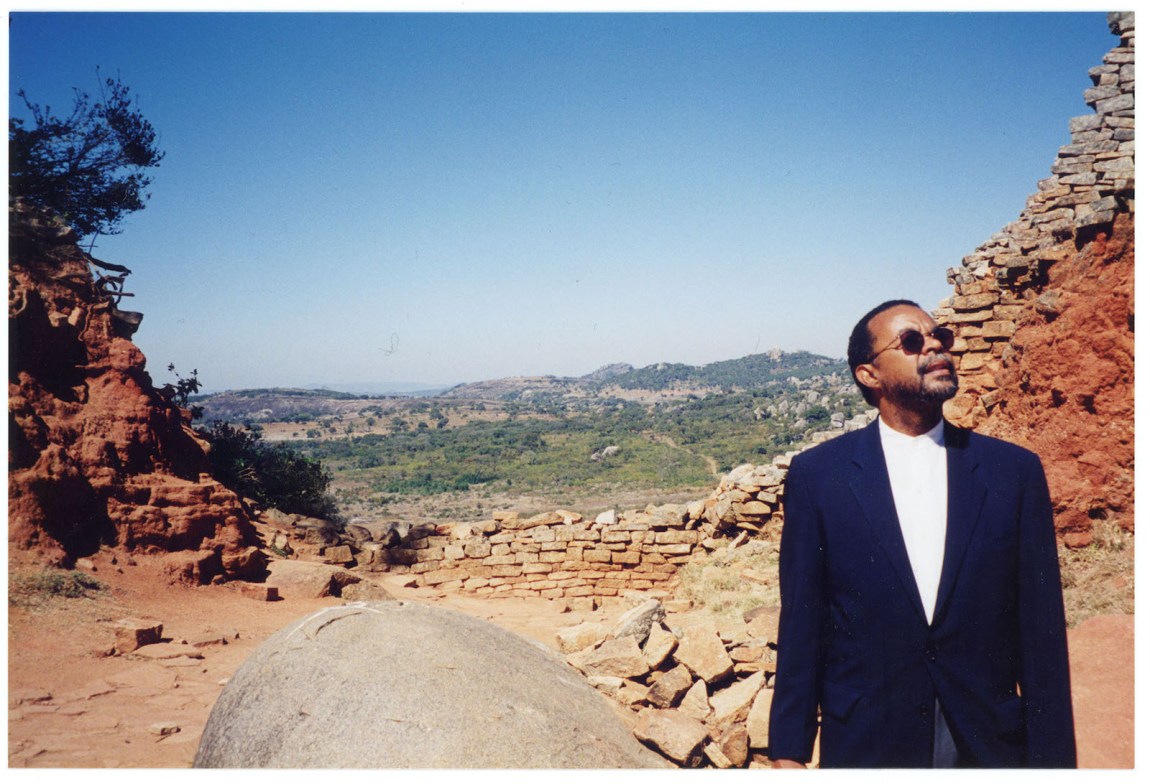

It was the English producer Jane Root who, after seeing me being interviewed on a late-night British TV show, asked if I’d be interested in hosting documentary films about Black history—the secret fantasy that I had harbored since seeing Civilisation and The Ascent of Man. Jane brought me into the world of filmmaking, now my second career. All of a sudden—starting with a one-hour documentary for the BBC’s Great Railway Journeys, riding on trains with a film crew and my two mixed-race teenage daughters whose African roots I was hellbent on getting them to embrace, starting at Bulawayo and ending in that village where I had lived during my gap year from Yale—I had found my own method of storytelling.

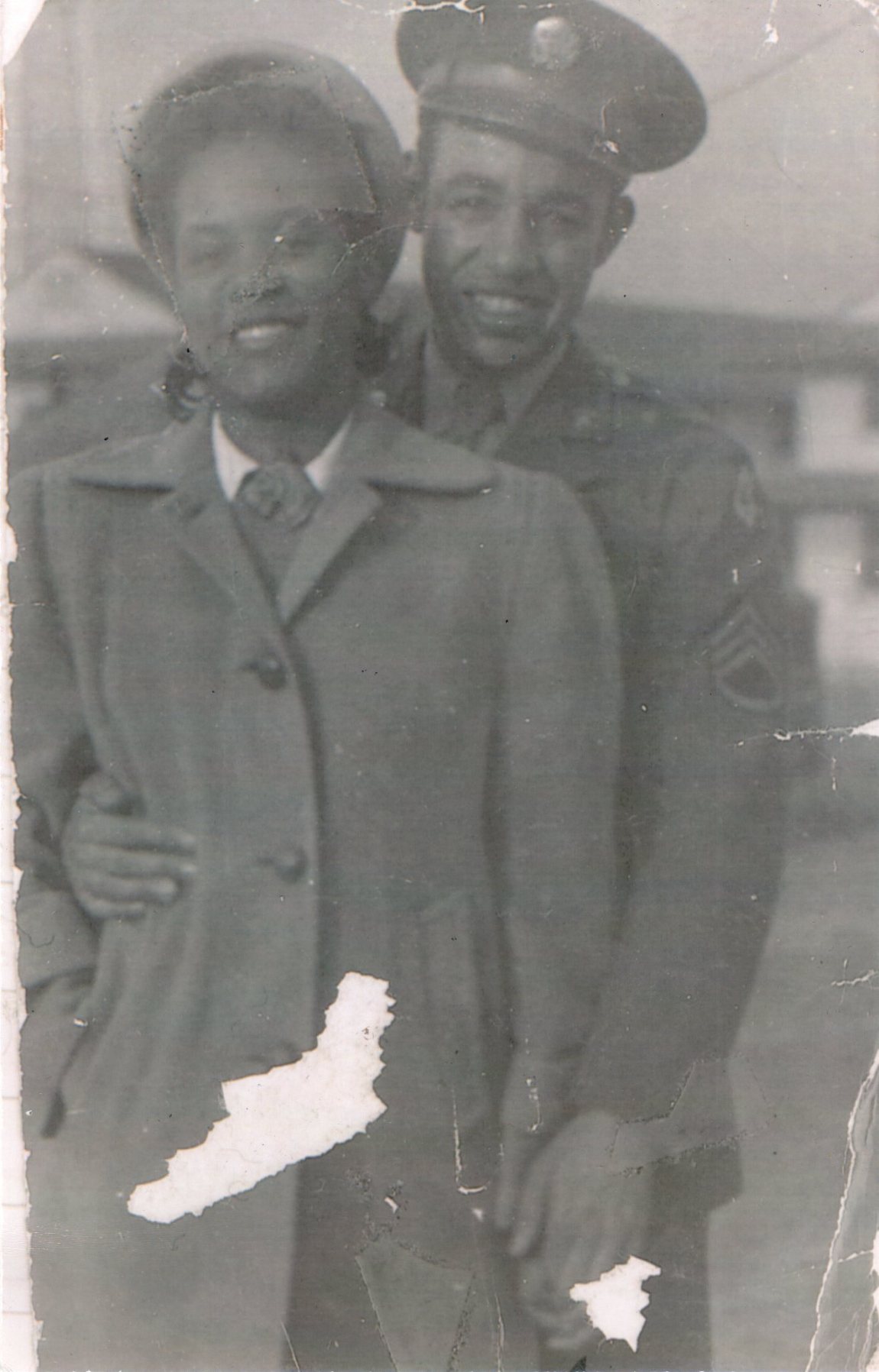

Two of my friends, both professional historians, like to tease me that I’m not “really an historian,” which of course I am not, because I only have a bachelor’s degree in history; my Ph.D. is in English literature. But I point out to them that, as far as I know, Ken Burns can’t play the saxophone and can’t hit a ball out of Yankee Stadium, but he’s made the best documentaries ever produced on the histories of jazz and baseball. I love writing books and making films about history because I love telling stories, and I owe a debt to the great storytellers who taught me: Bill McFeely, John Hope Franklin, John Morton Blum, Robert Farris Thompson, Walter Rodney, Kenneth Clark, Jacob Bronowski, Wole Soyinka, Kwame Anthony Appiah, Henry Hampton. The greatest of all was my mother, Pauline Augusta Coleman Gates. When I was a child she wrote all the eulogies for the colored people in the Potomac Valley, who read them in their funeral services. She published them in our weekly Piedmont Herald. It would take me a long time to realize that my first model of a storyteller, of an orator and a published writer, was the person who gave me life.

—September 16, 2023