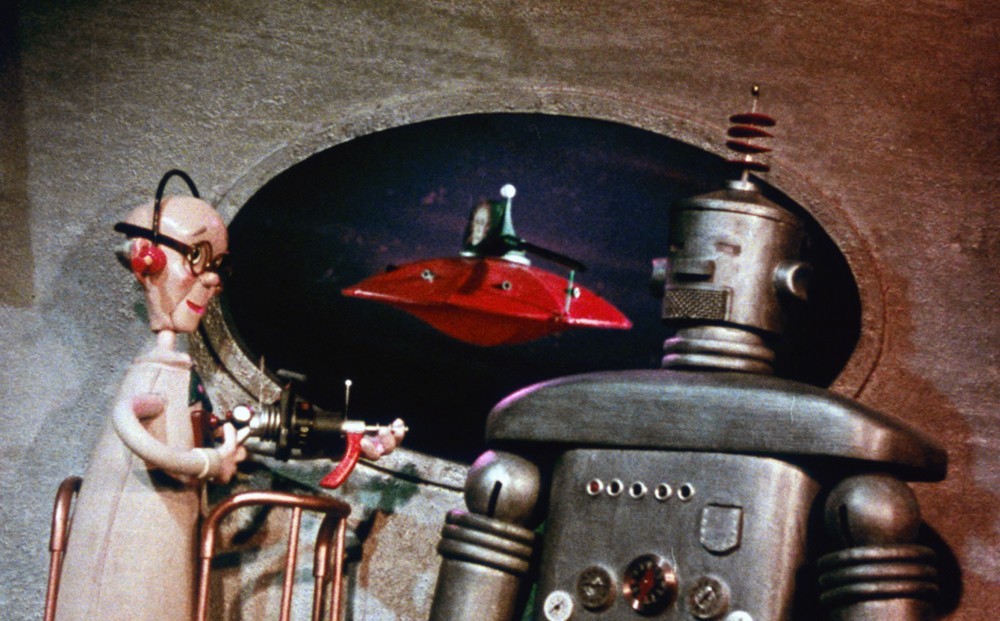

I just missed 3-D the first time around. I was four when Arch Oboler’s Bwana Devil hit movie screens in late 1952 to huge and unexpected success, and barely five as House of Wax, Robot Monster, The Maze, and It Came from Outer Space rolled out in the year that followed. These attractions were not in any case locally available, and by the time I was six it was all over. The great 3-D wave—Life thought it could be “the biggest boom since the advent of the talkies”—faded as rapidly and mysteriously as it had come. It was cut short at least in part by frequent synchronization problems (due to the two-projector systems then in use) and other technical glitches, along with the advent of CinemaScope (“The Modern Miracle You See Without Glasses!”), and perhaps an overload of boulders, flaming arrows, and any available pieces of furniture hurled toward the audience. The rumor lingered, however—the term “3-D” was added to the vocabulary of the very young as shorthand for some barely imaginable optical thrill—even if we were reduced in the meantime to getting our stereoscopic kicks in the inert form of ViewMaster slideshows that offered tableaux from Sleeping Beauty or scenic highlights of Florida, or from the occasional 3-D comic book.

Film Forum in recent weeks, in collaboration with the 3-D Film Archive, has offered an immersion in that first great wave under the rubric “A Deeper Look.” (The programs will continue until November 26, with work by Sirk, Boetticher, and Hitchcock still to come.) The archive has played a major part in the ongoing retrieval of that era’s bounty, and its founder Bob Furmanek has been on hand to give some idea of the tortuous difficulties involved in seeking out and restoring the scattered elements. At the start of each screening—no matter which of the varied features is showing—the audience registers an involuntary astonishment that kicks in even for those quite familiar with the process. The novelty somehow remains novel, if only for a moment. Even after one adjusts to the alternate sense of space that 3-D imposes, there continue to be flashes of surprise at otherwise ordinary things: a shrub or a hallway or a water fountain or a bit of drapery in motion will suddenly look alien, the crystalline excrescence of an unknown planet. With the glasses on, you yourself might alternatively be the extraterrestrial visitor looking at earthly phenomena through some prosthetic visual organ.

Somehow it always suggests the feel of a privileged experience, of being given access to the picture window in Captain Nemo’s submarine or the view from an orbiting satellite. The technical underpinnings of stereographic filmmaking are sufficiently arcane that they evoke a moment when the young at least could barely distinguish between science and magic. Miracles were promised, and here they were at least in small part delivered. 3-D was always taken as a harbinger of the future. Space travel and fully automated push-button living might have to wait a while, but here was a new frontier of perception for the price of a movie ticket.

The 3-D Rarities program screened at Film Forum moved in the other direction, burrowing further into the past by way of prologue to the world of 1953. Experiments with stereography go back to the nineteenth century, and 3-D film tests were publicly screened as early as 1915. In 3-D footage of New York and Washington, D.C. from 1922, said to be the earliest to survive intact, the visible age of the artifacts made them more uncannily futuristic, as if secret scientific experiments of an earlier era were being disclosed. The crucifixes in a historic cemetery jutted out of the screen like a buried past stirring into unsettling artificial life.

By 1940 the process was ready to serve as an advertisement for a world of wonders yet to come. In Thrills for You, the Pennsylvania Railroad unveiled the luxuries of the Broadway Limited and the epic scale of the ironworks where its cars were forged. At the New York World’s Fair, the Chrysler Corporation, to the blare of trumpets and bagpipes, pulled out the technological stops—3-D, Technicolor, stop-motion animation—to demonstrate step by step the making of their latest model. The resulting nine-minute promotional short, New Dimensions, is the romance of industrialism in concentrated dose, a musical extravaganza for dancing pistons and fenders: metallurgy made cheery for an audience still far removed from the war that was about to come calling. In retrospect it seems like so much advertising of that moment: a promise of the deferred comforts of a postwar world.

*

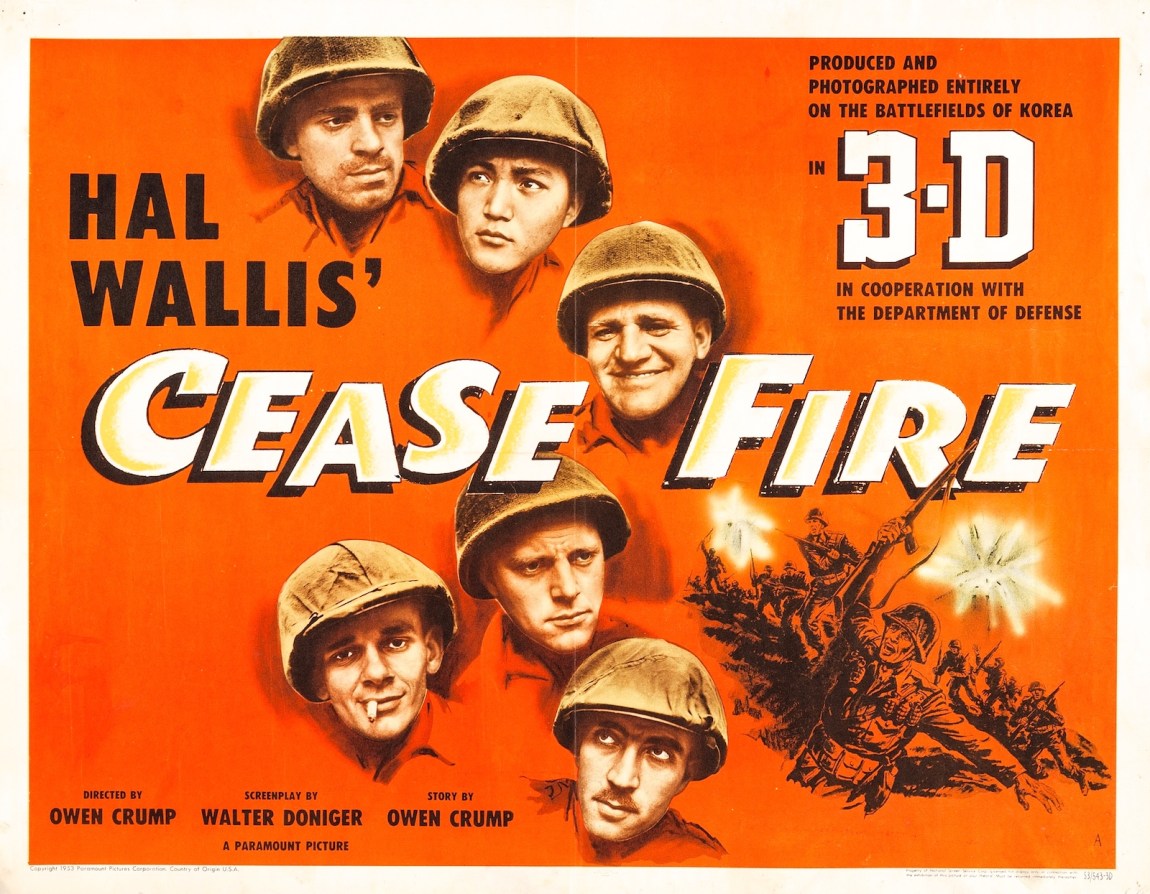

If 3-D represented the fun side of scientific progress, a new kind of toy that made everything look more exciting, it couldn’t help but channel some disturbance with its thrills. In 1953, with one world war just over, another conflict halted without a peace treaty, and a global nuclear standoff taking shape, cheeriness was a mood that could be imitated but not convincingly inhabited. Cease Fire!, a feature-length war picture filmed in Korea both before and after the armistice, with real soldiers and live ammunition, aims for the ultimate in realism despite a thoroughly fictional screenplay. The soldiers may recite their scripted and post-synced dialogue as if by rote, but they seem genuinely ill at ease in the unmistakably real terrain across which they advance. Their body language as they cautiously traverse a sandy minefield is thoroughly convincing. The 3-D process, sculpting surface textures, is perfect for enhancing the contours of a landscape or the bulk of an armored tank, but also for exposing any awkwardness or uncertainty of the humans moving through it.

Advertisement

Even more unsettling is Doom Town, perhaps the strangest item in the series, a fifteen-minute short presenting itself as a you-are-there report on an atomic test in Nevada, mixing documentary footage with the noirish musings of a journalist alone in his hotel room. An apparently authentic speech by a military spokesman is worthy of Dr. Strangelove (“with proper equipment and procedures, casualties resulting from an atomic bomb can be considerably limited”), but the film ultimately and unexpectedly strikes a tone of perturbed misgiving about the morality of nuclear weapons. This oddity had a few commercial screenings on the West Coast (“Electrifying! Climax Thrills in 3-D Color!”) before being yanked from view.

Doom Town’s remarkable rediscovery is like the return of the repressed, positioning one technology against another in a most jangling juxtaposition. An atomic mushroom cloud pops up as just another artifact of that moment, along with the battlefields of Korea, Biff Elliot as Mike Hammer (bringing the paperback cover art of I, the Jury to three dimensions), UFOs, Rita Hayworth going into her dance in Miss Sadie Thompson, the Gill Man from the Black Lagoon, and Rock Hudson as Taza, Son of Cochise: each to undergo the same attentive gaze, since the point is visual perception. The Diamond Wizard, a British thriller released near the end of the 3-D cycle, would not make much of an impression—for all the urgency of its warning that the manufacture of undetectable synthetic diamonds could upend the world economy—if it were projected flat. But here plot and characterization become mere conveniences to link a stream of visual pleasures, pleasures having little to do with the storyline or the pedestrian mise-en-scène credited to the film’s star, Dennis O’Keefe. It’s simply that the most ordinary surfaces are sufficiently changed to become freshly interesting. The wall telephone in the corridor of a hotel or the model of an airplane on the reception counter of a TWA office become otherworldly sculpture, and even an alleyway or an escalator open cavernous perspectives.

The spectator gorges on the act of looking, as if for the first time. The obligatory bravura touches—a bat swooping out of the screen in The Maze or the Gill Man breaking through the water’s surface in Creature from the Black Lagoon—make the screen a porous membrane through which things can pass. The eye can be invaded by what it sees. At its crudest the result is an aesthetic of protrusion: whatever is not directly hurled at least juts out. The effect is at first shockingly real—a reflex of vulnerability kicks in—and eventually laughable, no more startling than a pop-up book. Such moments, calculated to pull the viewer out of the movie’s reality, were what people mostly remembered from 3-D movies.

More entrancing is the sustained sense of moving through an unfamiliar kind of space. That space can come to seem more real than the world with the glasses off, even though the hyperreality of its layered planes is more like a form of Cubism. (One need only imagine what it would be like if the world on the street actually looked like a 3-D movie.) The perspective may turn outward toward the twistings and convolutions of natural landscapes, or inward into a labyrinth of corridors and stairways. In the vistas of Westerns like John Farrow’s Hondo, with its sweeping horseback raids, or Raoul Walsh’s Gun Fury, with its stagecoach careening down a precipitous trail, the unfolding of the terrain like a topographic model can feel ecstatic. Yet the most powerful effect of 3-D is not of an opening onto rolling plains but of a claustrophobic burrowing into buried places, as when, in the Mexican feature El Corazón y la Espada, two Spanish knights crawl through an excruciatingly narrow tunnel beneath a Moorish stronghold.

Advertisement

Under the direction of William Cameron Menzies, The Maze likewise becomes a rigorously designed exercise in framing interiors as traps and the pathways out of them as dangerous lures. The stock Gothic ingredients—the innocent bride, the brooding husband, the Scottish castle haunted by an ancient secret, the locked doors and perpetual nocturnal comings and goings, the mysterious forbidden pool—provide an ideal libretto for one stunning composition after another. It hardly matters that the plot resolution, when it comes, is of legendary absurdity. Menzies accomplished what was surely his intention, an exquisite demonstration of 3-D’s formal possibilities. The dark corridors and recesses of a low-budget castle were as good a place to stage it as any.

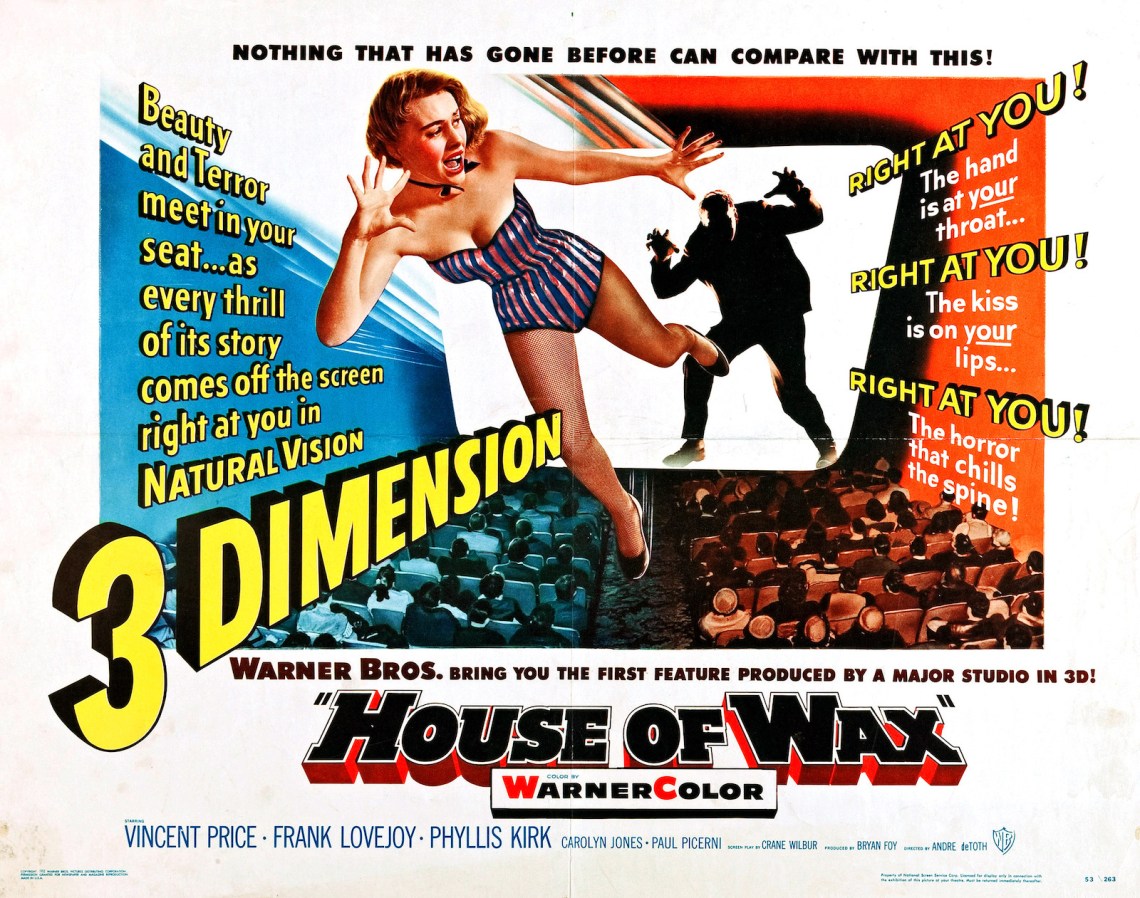

An even more convincing demonstration came from André de Toth with House of Wax, the first 3-D feature from a major studio (Warner Bros.) and by the far the most successful. That de Toth was one-eyed caused some stir, but no one could question the precision with which his film was laid out, most startlingly in the long sequence in which Phyllis Kirk is chased over a rooftop and through foggy streets by Vincent Price in black wide-brimmed hat and cape. Here the empty streets of 1890s New York are themselves the trap, and the pursuing predator a three-dimensional demon straight out of an old-time carnival poster. Unlike Menzies’s monochrome Maze, House of Wax is bright and colorful, with room for stunts, jokes, and a racy floor show, all the elements for an amusement park attraction. But it knows where it is going: de Toth shows what the technology of the future can do by descending into the past, into the basement under the waxworks chamber of horrors.