“Did you catch this?” the program insert for the John Golden Theatre’s production of The Shark Is Broken asks audience members. “Be on the lookout for the yellow barrel in the set from the original Jaws film!” I’m sorry to say that I failed to catch it. The same thing happens to me every time I go into Trader Joe’s and see that sign by the entrance exhorting shoppers’ children to look for the hidden monkey somewhere in the store. Luckily this has not prevented me from enjoying myself either at Trader Joe’s or at The Shark Is Broken.

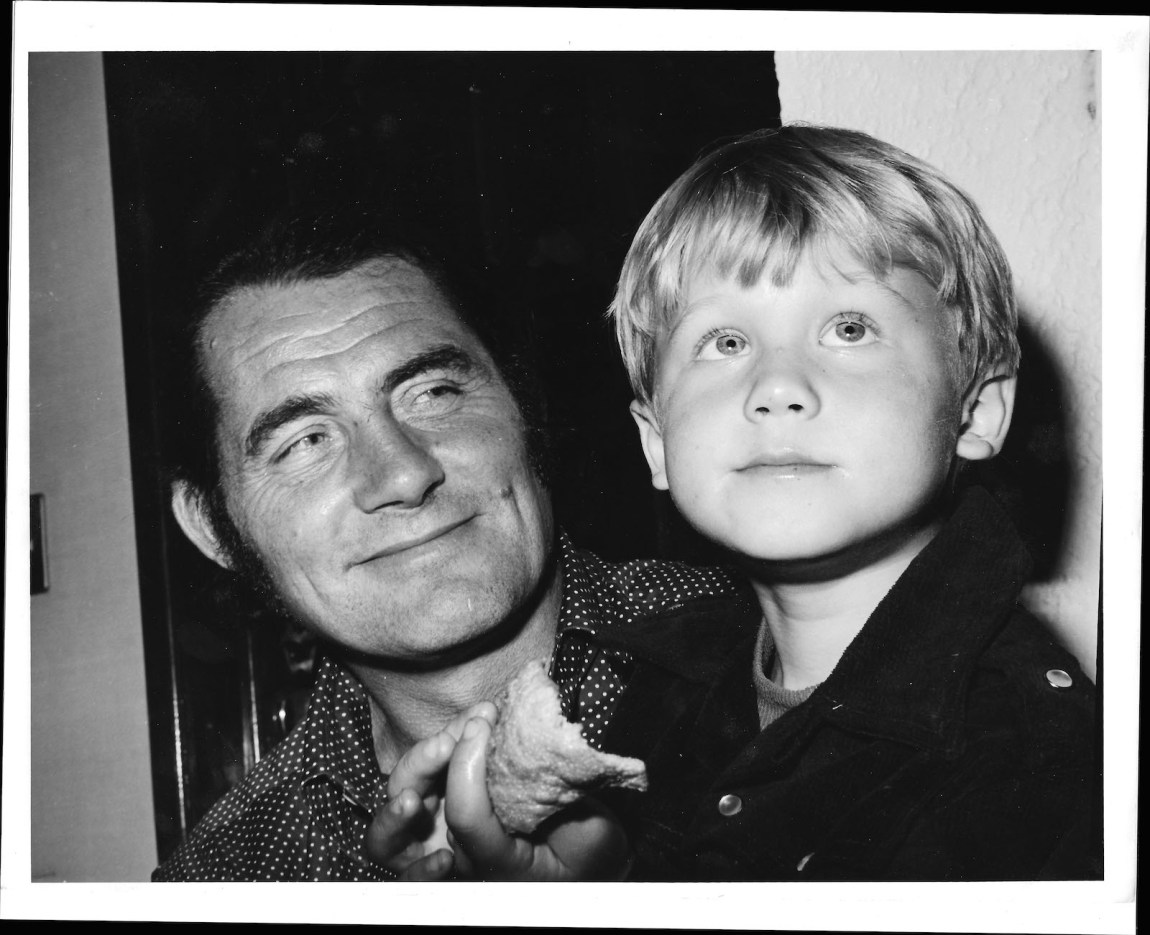

The play, directed by Guy Masterson, dramatizes the long weeks spent filming the oceangoing portions of the movie Jaws, when Roy Scheider, Richard Dreyfuss, and Robert Shaw comprised the cast. It was cowritten by Shaw’s son Ian, who also stars as his father, who played Captain Quint in the film. “In 2017 I read a drinking diary my father kept, which I found painful and very brave. I had a mustache for another role I was playing. Suddenly I realized I looked like Quint,” begins the author’s note on the reverse side of the barrel notice. “I thought about my father’s drinking, and I realized I had a mustache” has the same banal-yet-timeless quality as “The serpent deceived me, and I ate”—it’s the helpless kind of understatement that sometimes accompanies profound truth. Realizing you’ve come to look like your father without meaning to is, after all, a helpless condition; you might as well revisit his past, while you’re at it.

And it really does seem like a wasted opportunity not to have written and starred in such a play when you’ve got a face that’s a near-perfect match for Robert Shaw’s, and his drinking diaries to boot. (I realize this is a matter of opinion, but for my money there’s not a more attractive man in American cinema than Shaw in Jaws, although I will accept competition from Gary Cooper in City Streets.) Ian Shaw also has more going for him than his patrimony: he’s nervily magnetic, boisterous and often menacing onstage, and never becomes so attached to delivering a faultless impression of his father that he fails to create something original.

The Shark Is Broken presents an idealized version of imperfect fatherhood, where a father’s failings are the same as the failings of twentieth-century Western masculinity, as if to say: My father was charismatic, intimidating, and unpredictable; other men wanted his approval and did a lot of push-ups in order to try to win it. (Alex Brightman, playing Richard Dreyfuss, does all the push-ups in the play; Colin Donnell, as Roy Scheider, never tries to do any, although he does eventually strip down to his underwear in a furious, failed attempt at sunbathing. Shaw never does pushups or takes his clothes off, because he doesn’t have to.) Sometimes Shaw offers that approval and sometimes he conceals it, but on stage, approval is always his to extend or withhold.

While at sea, the real-life Dreyfuss, Scheider, and Shaw were often drunk, seasick, and trapped onboard their ship for days at a time, waiting for the weather to clear or for someone to repair the easily damaged pneumatic systems of the movie’s three mechanical sharks. The Shark Is Broken opens with the failure of one shark to work on cue, and the story is only restored to the original Jaws continuity in the last four minutes, making it a show primarily about what happens when Jaws breaks down, when inevitability stalls, and when dread fails to arrive on schedule.

The characters Dreyfuss, Scheider, and Shaw (Donnell, Brightman, and Ian Shaw are the only actors who appear on stage for the whole run of the show) frequently and pessimistically wonder whether the movie can possibly make money or even be finished. While they wait to be called to set, Scheider reads the newspaper and drinks a little, Dreyfuss peppers Shaw (his senior by twenty years and by far the most experienced actor, having received an Oscar nomination in 1967 for playing Henry VIII in A Man For All Seasons) with questions about acting, requests to be put in touch with Harold Pinter, and seemingly anything and everything else that scuds across the transom of his mind, often to Shaw’s annoyance. But Shaw’s success in Hollywood (cemented with back-to-back villainous turns in the 1973 megahit The Sting and 1974’s The Taking of Pelham One Two Three) had come relatively late in his career, and he was swamped with tax problems, unable to turn down work in order to support his ten children, and drinking heavily; he frequently left production to avoid taxation with trips to Canada. He died of a heart attack near his home in Ireland just three years after Jaws’s release.

Advertisement

Like the pneumatic sharks that the cast collectively nicknamed “Bruce,” the filming schedule has to operate around Shaw’s intermittent “brokenness.” Scheider and Dreyfuss may have their own flares of frustration and bouts of uncertainty, but they are always ready to work; Shaw’s relationship to readiness is more perverse and, as a result, more important. The contingent fantasy of The Shark Is Broken is therefore not “What if Jaws had never been finished?” but “What if my father were more dangerous than a shark? What if his faults only made other people want him to like them even more?” Reexamining a sentimental image of one’s father—even if it is gently done, even if it relies on preserving a sentimental mythology—can be a worthwhile subject for a play. And the “warts-and-all” depiction of alcoholism is a wildly sentimental genre, riddled with familiar hallmarks—the hidden bottles, the sudden swerves between the maudlin and the belligerent—where tragedy is always followed, and undercut, by a retreat into vulgarity.

*

Charles Dickens modeled David Copperfield’s Mr. Micawber on his own imperfect father and gave him the relentlessly optimistic slogan “Something will turn up,” which he deploys early and often, even in the face of relentless disasters. Mr. Micawber receives in fiction a happier ending than John Dickens experienced in life, sailing with his family to Australia where he becomes a bank manager and a government official. Something does turn up. Robert Shaw’s triumph in The Shark Is Broken is more miniaturized (it’s no spoiler to say that they do finish filming the movie Jaws): he successfully delivers the celebrated USS Indianapolis monologue in front of the camera.

This scene is the only part of the “filming” shown onstage, and it’s the third take we see. The first is cut short when Shaw denounces the monologue as written and demands the chance to rewrite it. The second time he’s too drunk and keeps forgetting his lines and cracking jokes, while the third time—I think the play’s producers would want us to think that he “nailed it,” although I found myself wishing that they’d start this round with anything besides the inevitable “Japanese submarines slammed two torpedoes into her side, Chief….” Ian Shaw adds a choked, elongated pause between “Anyway” and “we delivered the bomb” that’s not present in the movie, and his version is immediately followed by a loud, affectless “CUT.” I’m of two minds about these additions. On the one hand, it’s hard to argue that either element improves upon the original; on the other, the thin, cartilaginous layer of bathos that they add to the scene is probably characteristic of the bathos that always separates our fathers from our ideas about our fathers. What else is a son, if not an abrupt and anticlimactic transition from high to low style? Anyway, he delivered the joke.

The Shark Is Broken ends here, which is, I think, a mistake, since the primary dramatic concern of the play is actually a Russian nesting-doll exploration of anxiety about the work of performance and not “Will Robert Shaw be able to sound really cool while he delivers the USS Indianapolis speech in Jaws?” The Richard Dreyfuss character worries aloud that acting isn’t a sufficiently masculine profession; in another scene, Shaw explodes during an enumeration of all the technical skills the crew members have and the actors lack, which enable them to fix the shark and film the action. The audience gets to watch three actors embody a previous generation’s fears about whether acting is inherently effeminate or ridiculous, a crisis of middle-class masculinity at least two steps removed from the source.

The Shark Is Broken is forever removed from the source, but rarely departs from it; the dynamic between Shaw, Scheider, and Dreyfuss presented onstage is largely the same as the dynamic between Quint, Brodie, and Hooper onscreen. As they kill time playing games like poker and ha’penny shuffle, they discuss what they think the movie might be “about,” prompted, as most of their conversations are, by Dreyfuss’s nervous energy. He suggests the possibility of something Freudian, of subconscious, murky, primal forces that terrify us—an academic, Hooper-like explanation—while Scheider thinks it might have something to do with collective responsibility and how failure to respond to a threat in sufficient time endangers everyone, an appropriate concern for a sheriff. Both possibilities set Shaw up nicely to puncture their overdetermined delusions, as he roars, “It’s about a shark!,” the modest wisdom of which really spoke to the Saturday matinee crowd. Getting an audience to applaud you for saying the movie Jaws is about a shark is no mean feat, and I commend Shaw for it.

Advertisement

*

The biggest fault in the play is a tendency to rely on tired “prophetic” humor of the “Horseless carriages? Why, that’ll never catch on” sort, which nonetheless proved enormously popular with the rest of the audience: Scheider reads from the newspaper and predicts that “There will never be another president as corrupt as Nixon” (big laugh), Dreyfuss references Close Encounters of the Third Kind as “My next project? It’s about UFOs” (even bigger laugh), then asks, “Think there’ll be a sequel to this?” (huge laugh), to which Scheider responds “If there is, I sure won’t be in it!” (the biggest laugh of all). This is crowned by a dire prediction from Shaw that “One day there will be only sequels…and remakes…and sequels of remakes…what’s next, a movie about dinosaurs?” which brought the house down.

The jokes aren’t wrong, of course—almost every show playing on that same block of Broadway is adapted from well-known IP like Back to the Future, The Lion King, and Moulin Rouge!—but a little restraint would have been welcome. Too much of the humor depends on the contrast between what the audience and the play’s subjects know. It undermines the play’s dramatic interests; if we are reminded at every opportunity what a transformative, colossal hit Jaws is going to be, it becomes more difficult to enter into the actors’ shared fears that Jaws will be a flop, or remain forever unfinished. The show is on more solid ground with the aggressive slapstick routines that occasionally interrupt their conversations, and with Shaw’s drunk and pointed deployments of classical monologues, usually directed at Dreyfuss, to remind him what he thinks real acting sounds like. This is their real crisis: not only are they afraid that acting is not “real man’s” work, they also fear the pointless rumination that often arises when creative work becomes impossible, the theatrical equivalent of writer’s block.

The problem in The Shark Is Broken is not that the shark is broken; it’s that no one we’re watching has any skills that might enable him to fix it. When people cannot be effective, they brood, and Donnell, Brightman, and Shaw brood very well together, in both senses of the word, since more often than not they form a funny little family unit, with Robert Shaw as the withholding father, Dreyfuss as the promising yet exasperating son, and Scheider as a carefully neutral, inwardly raging mother. Donnell’s tight, quiet fury when Scheider is interrupted during his long-delayed tanning session is particularly pleasurable, although all three get at least one shot at a really good breakdown. Brightman gets the lion’s share of them, although it might be more correct to say that he plays Dreyfuss as a near-continuous series of breakdowns that are occasionally interrupted by accidental bursts of poise.

The real Richard Dreyfuss is reportedly displeased with how he’s been represented. I suppose I can understand, but there are far worse fates than being depicted as an enthusiastic, self-conscious, affectionate, and ambitious actor. Brightman’s Dreyfuss is technically impressive, generous, and generative; he makes developing flop sweat a pleasure to watch. Around the halfway mark (there is no intermission) Brightman rehearses the “Dreyfuss laugh” and a single line from the movie so many times it becomes inhuman, then impersonates Shaw-as-Shaw and Donnell-as-Scheider reacting to himself-as-Dreyfuss, which goes a long way toward allaying the risk that a play based on an extremely popular and regularly quoted movie would collapse into nothing more than a series of quotes, bits, and impressions. The pleasure in Donnell’s more mannered, constrained performance as Scheider unfolds more slowly, but in equal measure.

There’s got to be more to a show like The Shark Is Broken than mere nostalgia (“If you liked Jaws, you’ll love this play where we remind you about how great Jaws was: Remember the Indianapolis speech? And remember “Spanish Ladies”? And remember “You’re gonna need a bigger boat”?), since the first hit of nostalgia is invariably the most powerful and each subsequent draw offers diminishing returns. And while it is not above asking its audience, “Hey, remember the Indianapolis speech? Wasn’t it terrific?,” there’s fortunately much more on offer once they’ve settled the question. There’s an examination of celebrity before it becomes quite sure of itself and of fatherhood after last call; of men at work, not yet working.