I remember the first time I saw Meredith Monk perform; anyone who’s seen her in concert does. It was at the National Sawdust in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, on November 17, 2016, less than ten days after Donald Trump was elected president—the beginning of a nightmare from which we’ve yet to awake, the sort that Monk has long been warning about in her music. A slender, diminutive woman with long braids as distinctive as the streak of gray in Susan Sontag’s hair and a beatific gaze that masks a steely determination, Monk faced us at audience level on a stage barely larger than a living room. “I think we’re all in need of lullabies now,” she said as she sat at the piano and performed her piece “Gotham Lullaby.” Her cries, hesitations, and pauses nearly brought me to tears.

My experience was remarkable but not unusual. When I took a friend who’d been going through a difficult time to hear Monk—who has achieved renown not only as a singer and composer but as a choreographer, dancer, and filmmaker—she told me that the performance reminded her of “what mattered,” chasing away her anxious thoughts. The composer and critic Kyle Gann writes that when he first “fell under her spell,” he felt as if he were listening to a shaman. Monk’s effect on her audience is reminiscent of the feeling that Freud famously called “the uncanny,” that simultaneous sensation of strangeness and familiarity. Few of us are accustomed to music made of the clicks, chirps, wails, ululations, growls, drones, and other sounds that Monk makes with her three-octave, vibratoless voice. But these sounds, however strange, are also evocative of memories (and not only acoustic ones) that most of us have in common—of pain and joy, of fear and exhilaration, of celebration and sorrow. Monk’s work has a way of bringing it all back home, back to the experience of being human: our relationship to others, to the natural world, and to ourselves. She belongs in that select company of artists—Ingmar Bergman, John Coltrane, and Pina Bausch are others who come to mind—who shatter our defenses and force us to take stock of our lives.

And she does it all without words. On the rare occasion that Monk uses words, they appear as lists or chants rather than expressive or narrative lyrics, and they’re usually delivered without affect. It’s not that she has no love of language. On the contrary, she’s a passionate reader of literature and spiritual philosophy, and has often found inspiration in her readings, from Paul Celan’s poetry to Siddhartha Mukherjee’s history of cancer, The Emperor of All Maladies. Yet she has long felt that words get in the way of the “visceral, primordial psychic states” that the voice (“the messenger of the soul,” as she calls it) is uniquely capable of capturing. Monk, who thinks of herself as an “archaeologist” of sound, has spent the last six decades excavating the “original utterance,” the voice in all its richness and variety, unobstructed by the “filter” of words. The New Testament had it wrong: In the beginning was the Voice, not the Word.

If you doubt this—or if you haven’t heard Monk’s music—please put this essay aside and listen to “Gotham Lullaby.” The first track on her 1981 album, Dolmen Music, it begins with a four-note, minor-key motif played on the piano, repeated sixteen times before we hear Monk’s voice. Her entry is consoling, if baleful, yet she soon punctuates her singing with mournful wails and squeals that seem to conjure the nocturnal terrors from which lullabies are designed to protect children. The ending has a calm and beautiful melancholy, but it’s no victory over those cries and whispers in the night, just a temporary repose. Like all of Monk’s work, “Gotham Lullaby” does not hypnotize, much less put us to sleep; instead it sharpens our sense of awareness, in spite of—or rather because of—its wordlessness.

*

In 1976 John Cage came to Monk’s dressing room after hearing her sing with the dance company led by his collaborator and life partner, Merce Cunningham. “Meredith, where do those voices come from?” he asked. She looked up to the sky, as if to a higher power; they both laughed.

Cage isn’t the only person to have wondered about the origins of Monk’s vocals. Different listeners hear different sources—or different points of reference—depending on their backgrounds, their experiences as listeners. Some hear an abstracted version of folk singers like Judy Collins or Joni Mitchell; others detect echoes of Balkan music, Pygmy music, or Mongolian throat singing. An Algerian friend of mine who loves Monk’s music says it reminds him of the great Kabyle Berber singer and writer Taos Amrouche.

Advertisement

In Western art music, the search for a new and more expressive kind of vocalizing is often traced to Arnold Schoenberg’s use of Sprechstimme, a style of talk-singing, in his atonal cabaret suite Pierrot lunaire, composed in 1912. In the Fifties and Sixties, composers such as Karlheinz Stockhausen, Luciano Berio, Luigi Nono, and Cage wrote pieces that employed “extended vocal techniques,” which required classical singers to use their voices in extreme and often theatrical ways, ways they’d been trained not to sing. In 1968 the Armenian American vocalist Cathy Berberian, one of the bravest practitioners of extended technique, published a manifesto defending forms of vocal expression “not yet ‘officially’ catalogued as emerging from musical experience.” The “elements constituting the New Vocality,” she observed, “have existed since time immemorial: it is merely their justification and musical necessity that is new.”

Monk was not aware of Berberian’s work when she first began performing in the early Sixties, but she understood that the recovery of what has “existed since time immemorial” is as much a part of innovation as discovery itself—and that recovery and discovery often amount to the same thing. What is more, unlike some of the exponents of the New Vocality, including Berberian herself, Monk did not have the burden of extensive classical conservatory training to throw off. Gann once praised Monk for having “purged” works such as Stockhausen’s choral piece Stimmung of their “intellectual pretensions.”

But Monk had never heard Stimmung (and still hasn’t, she told me). As much as she came to admire singers like Berberian, she found greater inspiration in folk musicians and soul and jazz singers like Nina Simone, who used her voice with a torrential force that not even Berberian could have imagined. One of Monk’s earliest recordings, featured in her 1966 performance piece 16 Millimeter Earrings, was a lovely rendition of “Greensleeves,” in which she accompanied herself on guitar. She also listens to many of the musical styles grouped under the absurdly Eurocentric rubric “world music.” Her favorite contemporary singer is the Brazilian musician Caetano Veloso, the pioneer of Tropicália.

And yet, unlike some of the minimalist composers with whom she’s still often associated, Monk has never sought to explicitly incorporate Indian, African, or Asian sounds in her work. The folk resonances of her music are not externally acquired: they flow directly from what she calls the “singing body,” from the research she has conducted on and with her own voice. And while other singers of her generation have mined the voice’s possibilities with comparable audacity—Jeanne Lee and Jay Clayton in avant-garde jazz or Joan La Barbara and Diamanda Galás in “new music”—no one has gone as far as Monk in developing the sounds of the “original instrument” into a distinctive compositional language. This achievement has made her a model not only for practitioners of “new music,” but also for adventurous popular singers like Björk, who performed her own version of “Gotham Lullaby” with the Brodsky Quartet.

The parallels between Monk’s work and other, especially non-Western, vocal traditions are, in large part, the result of serendipitous convergence, rather than influence and adaptation: similar sounds achieved via different routes. Yet they are also a tribute to her work’s ability to transcend national, ethnic, and other boundaries. Monk does not consider herself a “Jewish artist,” or for that matter a “queer or bisexual artist,” though she has loved both women and men. A defiant humanist, she describes her music as “stateless.” Thanks in part to its abstraction, her music is intelligible “in all languages,” as Ornette Coleman would say, or, as Monk herself might say, in the universal language of the human voice.

*

Throughout her career, Monk has been composing songs of experience, evoking both the joy and the suffering of being human—and inhabiting a body—in a world that is precariously poised between the threat of annihilation and the possibility of transcendence. Without any recourse to sentimentality or other manipulative devices, her music lays bare “what is fundamental,” in the words of the composer and singer Julius Eastman, a member of her ensemble in the early Eighties. For Monk, what is fundamental is also indivisible: sacred and profane, playful and serious, vernacular and modern, epic and intimate, sound and image, strength and fragility, body and soul. To weave together these separate elements (or separated, thanks to specialization or other coercive boundaries) is a matter not just of aesthetics but of repair and healing.

The idea of music as a form of healing is, of course, central to many traditions outside the West, and to the Black American musical tradition. (Albert Ayler: “Music is the healing force of the universe.”) But Western art musicians were long taught to hold in contempt the idea of music as healing or nurturing. In the Fifties and Sixties boys’ club of postwar classical modernism, music was supposed to be complex and demanding and (it almost went without saying, after the Second Viennese School) atonal. Its ultimate meaning lay in the score itself, or in the highly specialized process behind the score, whether it involved tone rows, chance operations, or visual notation. How it sounded was almost beside the point, never mind whether it gave pleasure. The title of Milton Babbitt’s 1958 article for High Fidelity, “Who Cares If You Listen?,” captured modernism’s disdain for the audience.

Advertisement

The early New York Minimalists, Philip Glass (born 1937) and Steve Reich (born 1936), rose up against this orthodoxy in the latter half of the Sixties. They wrote tonal music, grounded in a steady pulse, based on patterned repetition, and influenced by African, Indian, and Southeast Asian traditions. But their early work shared some of the assumptions of the academic serialist composers they challenged: it was often impersonal, even mechanical, in its devotion to structure and process. Glass’s Music with Changing Parts and Reich’s Drumming, both of which premiered in 1971, were as exquisitely refined in their attention to process as a wall drawing by Sol LeWitt or a sculpture by Richard Serra. As Glass writes in his memoirs, “The music world now could say, ‘This is the music that goes with the art.’” But, like the art in the galleries where Reich and Glass often performed, their early music was cool, detached, and emotionally restrained. Although propelled by rhythm, it still contained residues of what Monk calls “chin-up music.”

Five years younger than Glass and six years younger than Reich, Monk shared some of their predilections when she started out: an incantatory use of repetition and drones; an unabashed embrace of tonality; a fascination with non-Western, often sacred and ceremonial, forms of expression; and, not least, a blurring of the distinction between composer and performer. Yet her work was in no way an extension of theirs. (When she first met Glass, he was the plumber in her building; only later did she learn that he composed.) She had no desire to write music to illustrate the logic of a compositional process. Her aim was to convey the emotion of sound, not its structural direction, and to “go back to the body.” Because of her background in dance, her relationship to repetition and rhythm was more supple, more human, than the rhythmic cells in Glass’s work or the phase-shifting in Reich’s. On songs like “Travelling,” from 1973, her yodeling, ecstatic and yet rigorously modulated, suggested the “sheets of sound” that John Coltrane produced on the saxophone.

As much as Monk admired both Glass and Reich, she was after something more holistic, and more ambitious, than a musical analogue of minimalist and conceptual art: a new art form, expressive and corporeal, combining music, dance, and image into a total work of art. She also wanted to connect her music to her spiritual practice, something that she had in common with the West Coast minimalist Terry Riley. In their later work, both Glass and Reich would follow in Monk’s footsteps, writing more emotionally extroverted (and sometimes spiritually inspired) music and collaborating on operas and multimedia works with visual artists and directors. Monk has always involved herself in every detail of her work, even as she has worked in close collaboration with the musicians and dancers in her ensemble, or with the visual artist Ann Hamilton. No aspect of creation is foreign to her. The composer John Luther Adams, a friend of hers, told me that “if you were to encounter visitors from another planet, and they asked for signs of intelligent life on earth, a piece by Meredith Monk might be presented as evidence.”

*

Monk was born in Forest Hills, Queens, to parents of Jewish origin.1 She is, in her words, a “fourth-generation singer.” Her mother, Audrey Marsh, was the original Muriel Cigar singer, and performed in commercials and variety shows on the radio. Marsh’s father, a bass-baritone born in Russia, ran a conservatory in Harlem; his wife, Monk’s grandmother, was a classical pianist, his father a cantor. Meredith Monk has forged a striking synthesis of the three traditions represented by her family: the spiritual music of her great-grandfather; the classical music of her grandparents; and her mother’s popular song.

As a child she would often follow her mother to gigs and sit in studio control rooms while she performed. (She compares her childhood to Woody Allen’s film Radio Days.) “My mother was in the commercial world, and I knew I’d never fit into it,” she says. Nonetheless, it was Monk’s mother who recognized that she had a natural sense of rhythm, which has always been at the heart of her work. Monk began to play piano at age three, and in her teens she discovered Igor Stravinsky, Federico Mompou, and Béla Bartók (“my man,” she still calls him). At fourteen she took up guitar and was captivated by the sad beauty of English folk ballads: “Folk music had an honesty and a plangency, and I could play the character and persona of every song.”

“I did not have an easy childhood,” Monk says. The family had a comfortable life in Forest Hills, and later in Stamford, Connecticut, where they moved when she was seven, but she grew up in the shadow of the Holocaust, the bombing of Hiroshima, and the Korean War: “I’m always thinking about the earth as if it were going to end.” Her father, who ran a lumber yard, was away for most of her early years, heading the supply department of the Seabees, the US Naval Construction Battalions, in Guam. Since her mother sang on the radio almost every day, and often in the evening as well, Monk and her younger sister were looked after by Millicent Astwood, an elderly woman from Bermuda whom they both adored.

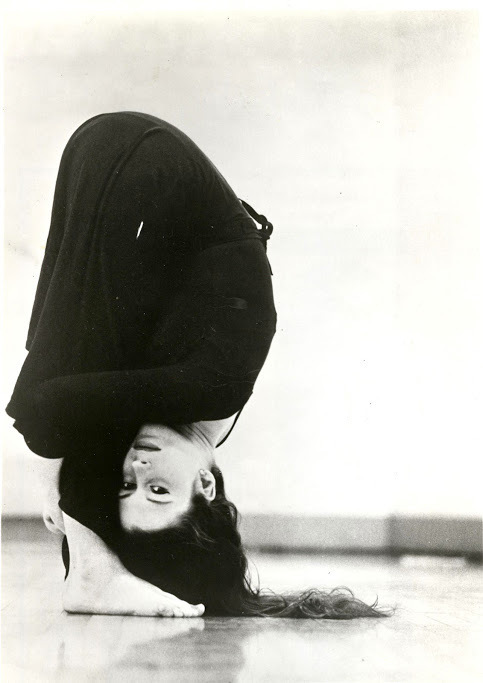

Small and physically awkward, Monk suffered from strabismus, a misalignment of the eyes that prevents her from seeing in three dimensions. Noticing that she had coordination problems, her mother enrolled her in Dalcroze Eurhythmics, a form of musical pedagogy based on movement. Émile Jaques-Dalcroze, who developed the method, believed that “all musical truth resides in the body.” This remains a virtual mantra for Monk.

When she arrived in the fall of 1960 at Sarah Lawrence College, where she studied dance and vocal performance, Monk finally met “people who understood me.” One of them was the dancer Carla Blank, who remembers her as “determined” and “hellbent on dance,” yet also sensitive to being an “outsider,” because of her strabismus and because she didn’t have “the typical dancer’s body.” Monk’s response to this acute sense of being different was not to try to adapt to the forms of conventional dance but rather to develop her own: “I knew that I was a person who needed to create. It was my creativity that brought me forward, and that transcended my physical limitations.”

She read Edmund Husserl’s writings on phenomenology and Alain Robbe-Grillet’s enigmatic novel La Jalousie (Jealousy), which taught her that art could be more effective by implying emotion than by showing it. In her composition class with Bessie Schonberg, a former Martha Graham dancer who directed both the dance and theater programs at Sarah Lawrence, she learned that certain principles of motion, structure, and form could apply to any medium and began to think of how to “weave together singing and moving,” the two artistic forms she loved most. Western art music, she came to realize, was unique in separating elements—composing, performing, singing, and dancing—that were more often fused in African and Asian cultures. A more integrated form, she concluded, might be “an antidote to the fragmentation and specialization of our world.”

These were rebellious inclinations in the early Sixties. Formalist modernism continued to exert a puritanical and repressive influence in the arts. Clement Greenberg, the high priest of this school, argued that artists should “derive their chief inspiration from the medium they work in,” to the exclusion of others. But by the time Monk arrived in Lower Manhattan in 1964, this orthodoxy was beginning to crumble, thanks to Cage, Fluxus, and Pop Art—and, in an adjacent scene, the multimedia collaborations of free jazz and the Black Arts Movement. It was, as Monk recalls, an “anything-is-possible time,” and she took part in the demolition crew that brought down the house of high modernism.

Her friend Rohana McLaughlin, whom she met in 1964 when they were both taking a class with the choreographer Judith Dunn, says her “fearlessness and commitment” were instantly evident. Monk presented pieces at the Judson Church and performed at the Café au Go Go, sang in a rock band called the Inner Ear, and recorded a single with the keyboard player Don Preston of The Mothers of Invention.2 She watched experimental films by Maya Deren and devoured Susan Sontag’s essay on science fiction, “The Imagination of Disaster.” She collaborated in Fluxus happenings with Dick Higgins, Alison Knowles, Jackson Mac Low, and Nam June Paik. “That generation really welcomed me, although they knew my sensibility was very different.”

What set her sensibility apart was, as she puts it, her “emotional intensity as a performer.” Much of the new art made in New York in the latter half of the Sixties thumbed its nose at emotion in favor of “objective structures” (the obsession of the new sculpture) or “process” (the obsession of the new music). “Even at that time,” Monk recalls, “my work was between the cracks.” In one of her journals, she wrote:

Most people only think of the containers, the names, the certain times, the repeatability, the objecthood. In theater process, mixture—category-less-ness—is not understood. Sometimes inconsistency is actually consistency.

What Monk meant was that her “inconsistency” was a form of fidelity to her vision of integrating the arts in live performance.

The foundation of this work was, from the very start, her voice. “Sometimes it takes you a long time to sound like yourself,” Miles Davis once said. Monk first began to sound like herself at the age of twenty-three, a year after her arrival in New York City. She was vocalizing at her piano, in her loft in Lower Manhattan, when she “realized in a flash that within the voice were limitless possibilities of sound, texture, character, gender, resonance, ways of producing sound”:

From that time on, I began working with my own instrument—trying to discover the voices within. I explored the various resonances, ways of using breath, lips, cheeks, and diaphragm. I also worked with the extremes of my range and quick changes from one vocal quality to another so that my voice could be a flexible conduit for the energy and the impulses that began to emerge.

The voice, her voice, was eloquent, and portable: she didn’t even need a suitcase to travel with it. And the voice afforded “a more direct kind of communication” than any other.

Two other revelations followed. The first occurred when she heard a performance by La Monte Young, Marian Zazeela, Tony Conrad, and John Cale. “You could hear drones through the whole building,” Monk recalls. She went in with a headache, but after a few hours it disappeared and she felt curiously refreshed. The experience of Young’s drone music led her to reflect on “fundamentals,” on stripping things down to their essence.

Not long after, she heard Janis Joplin perform and “realized that beauty is anything you want it to be”: there was no reason to fear the strange sounds she was making. Thelonious Monk had suggested as much in a song he recorded a few years earlier, “Ugly Beauty,” and Meredith loves the music of her namesake. “Monk gave us the bones and allowed the listener to fill in the rest,” she says. And while Meredith’s work sounds nothing like Thelonious’s, both artists share a sense of wonder that is often dismissed as “childlike,” though it is achieved only by artists of the greatest depth. As Meredith puts it, “play is something to really think about.”

*

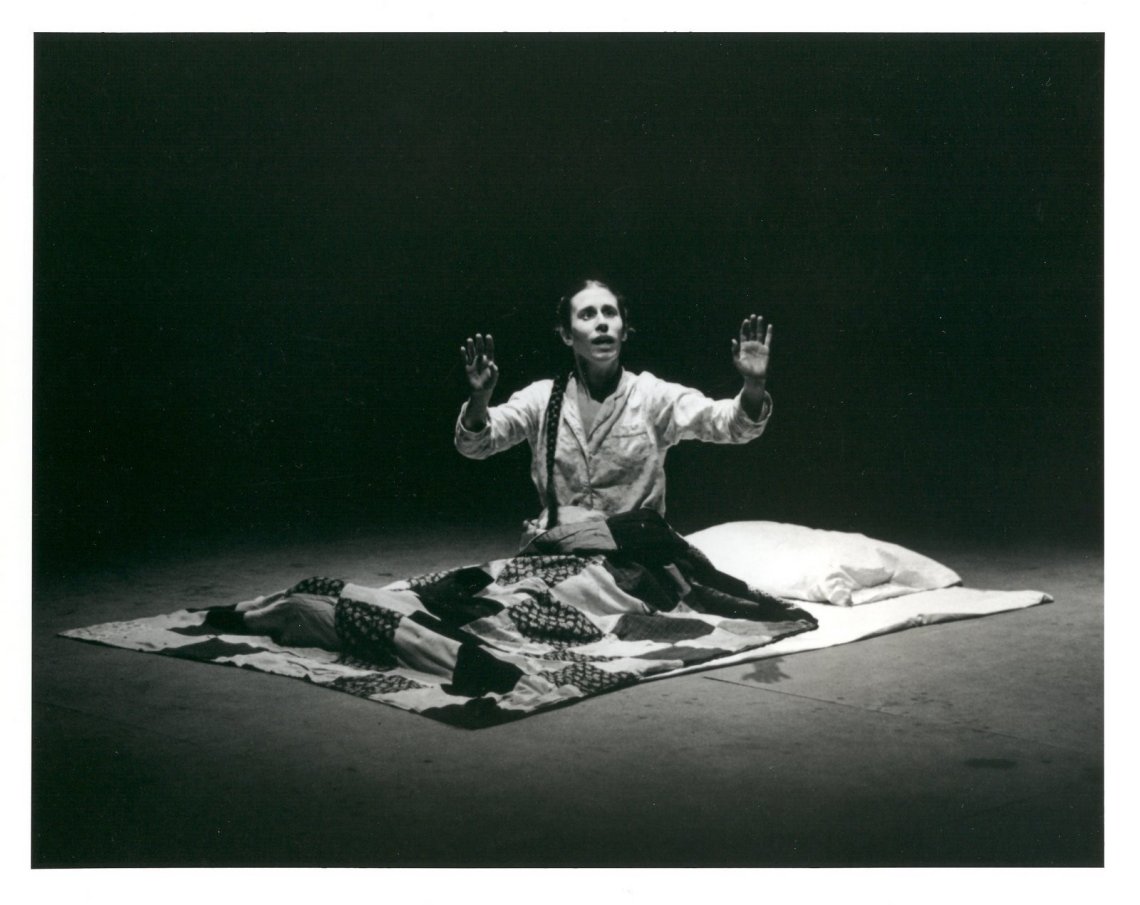

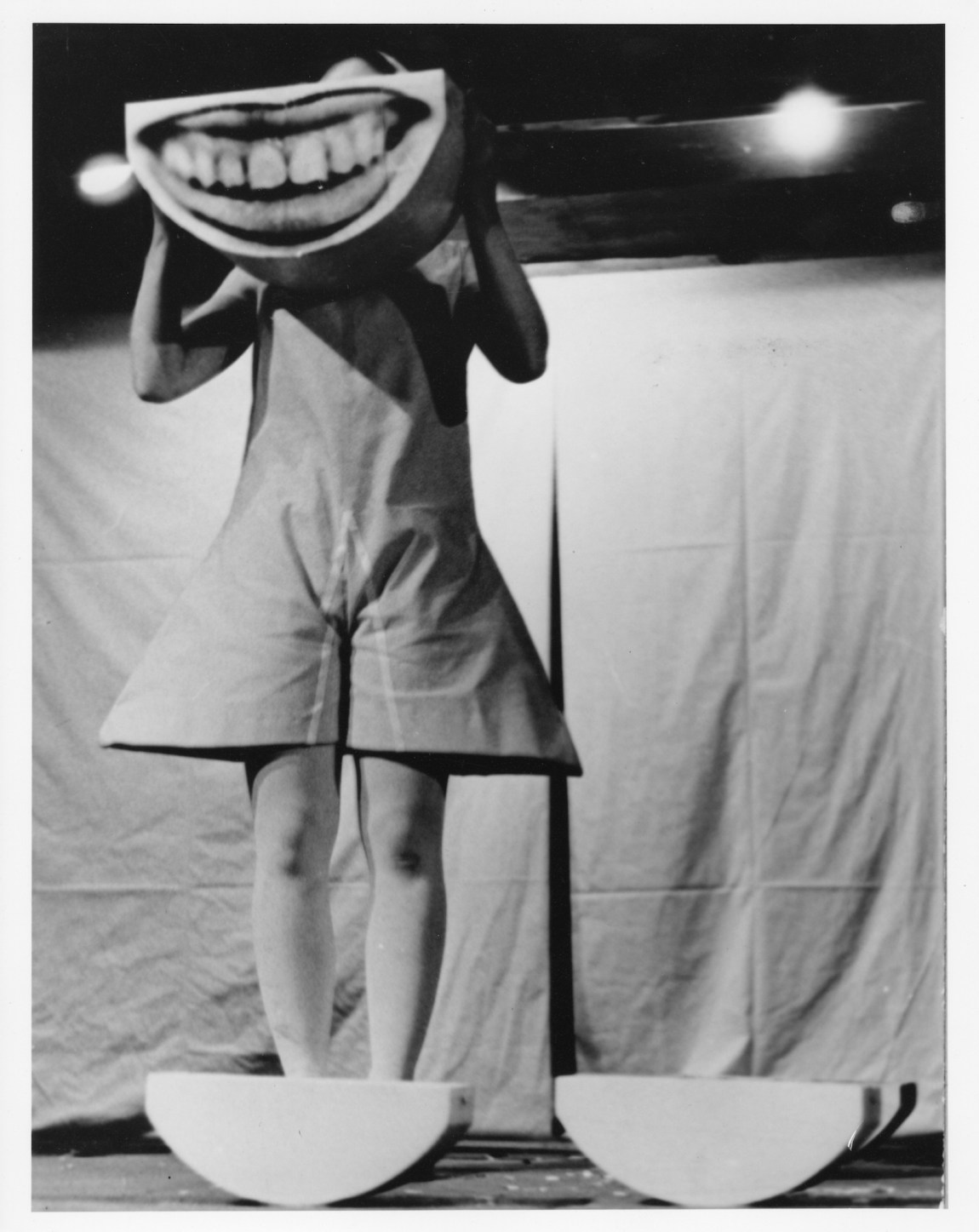

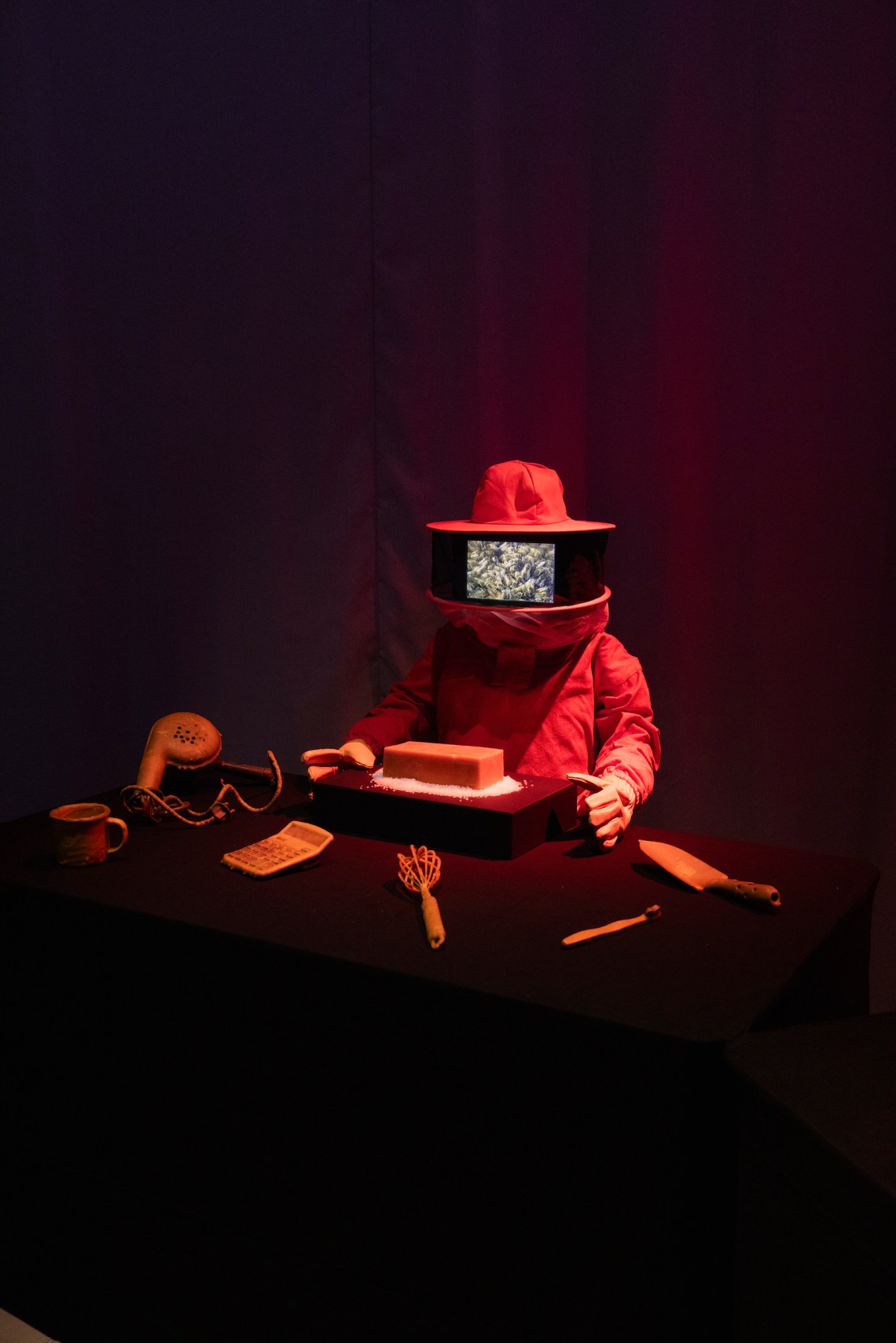

In December 1966 at the Judson Memorial Church—a year after she stumbled upon the continent of her own voice—Monk premiered 16 Millimeter Earrings, a half-hour work of wild yet formally rigorous musical theater, alternately whimsical and ominous. Set to a chantlike piece called “Nota,” progressively distorted by tape loops, and to an inexpressive, methodical reading of Wilhelm Reich’s essay on orgasm, the piece was a collage of movement, film, recorded sound, light, and kaleidoscopic objects. At the center of it was Monk herself, the sole performer, who at one point looks as though her head is in flames. 16 Millimeter Earrings was her way of “looking at emotion through a lens, one that wasn’t psychoanalytic or personal, but archetypal.” But her search for the archetypal, or mythic, resembled her investigation of her own voice: she located it within herself. Although Monk’s work was not didactic, it reflected—or rather anticipated—the emerging ethos of second-wave feminism, especially its affirmation of women’s bodily experience.

16 Millimeter Earrings was also formally innovative for its experimentation with tape loops and its live integration of different media. But while Steve Reich’s 1966 composition Come Out, which premiered several months earlier, is still recognized as a pioneering tape loop work, few people outside Monk’s circle remember 16 Millimeter Earrings. “If you are a woman,” Monk’s friend the artist Carolee Schneemann wrote, “they will almost never believe you really did it…they will try to take what you did as their own/(a woman doesn’t understand her best discoveries after all).” After reading this text at Schneemann’s memorial service in 2019, Monk sighed, “Ah, I wish I had known that!”

At the beginning of her career, men on the Downtown scene often treated her “as if being driven and assertive and doing my vision was really bad because I was not a supporter and nurturer of men.” Male critics didn’t know quite what to do with her work, belittling it even as they praised it. In a review of an early Monk performance, John Rockwell of The New York Times wrote, “Miss Monk is so earnestly strange in her precociously talented-little-girl way that it takes a while to accept her premises and to appreciate her properly.” But the free jazz saxophonist Sam Rivers and the Brazilian percussionist Naná Vasconcelos immediately embraced her work and urged her to “go for it.” She was not to be discouraged, in any case: art was “a matter of life and death” for her, as essential as the bread she baked and served to guests at her Tribeca loft when she gave morning performances there.

In Monk’s operatic pieces of the early Seventies, such as Vessel (inspired by the legend of Joan of Arc) and Education of the Girlchild (about the adventures of five women at different stages of life), she sought to fuse the epic and the intimate dimensions of female experience. “We have Parsifal, we have King Arthur and the Knights of the Roundtable,” she said, “What about a group of female characters?” Her most enthralling early compositions were portraits of women in which she often sang alone, accompanying herself on piano or organ. Some of them are quite funny (Monk’s sly wit is one of her most overlooked virtues): in “The Tale,” one of her rare songs with words, an old woman exclaims, “I still have my hands/I still have my mind/I still have my money.” But most of them plunge into a well of primal emotions, beyond language, although we may find ourselves translating her sounds and syllables into words, as we might imagine figures while looking at an abstract canvas.3

While the lives she explored in works like Education of the Girlchild may not have been classically heroic, the emotions they conjure are nothing short of epic, and Monk seemed to know them herself. When she wrote “Do You Be,” a lacerating piece for solo voice and electric organ, at her loft on Great Jones Street, she had the sense that it “came from a larger intelligence that was ‘singing’ me,” that “came through me rather than from me.”4 That sense of being a vessel for ancient forms of expression was shared by her collaborators. Lanny Harrison, who performed in both Vessel and Education of the Girlchild, told me that the thrill of working with Monk was that “you could dig deep into yourself, into your own connection to myth and storytelling.”

Monk has always expressed a resistance to narrative, and it’s true that her music seldom has a sense of linear progression. But there are many ways of telling a story, not all of them linear. In these early pieces, and in later works like her 1988 film Book of Days (about a Jewish girl in the Middle Ages) and ATLAS (her 1991 opera loosely inspired by the explorer and spiritual seeker Alexandra David-Néel), Monk has revealed herself to be an original and imaginative storyteller. She teaches her compositions to the members of her ensemble through aural instruction and memorization over months of practice, rather than by handing out a score: the experiences embodied by her music must be passed on mouth to mouth, since, in her work, each singer is a storyteller. The aural tradition, Monk says, “gives the music a more kinetic quality.”5

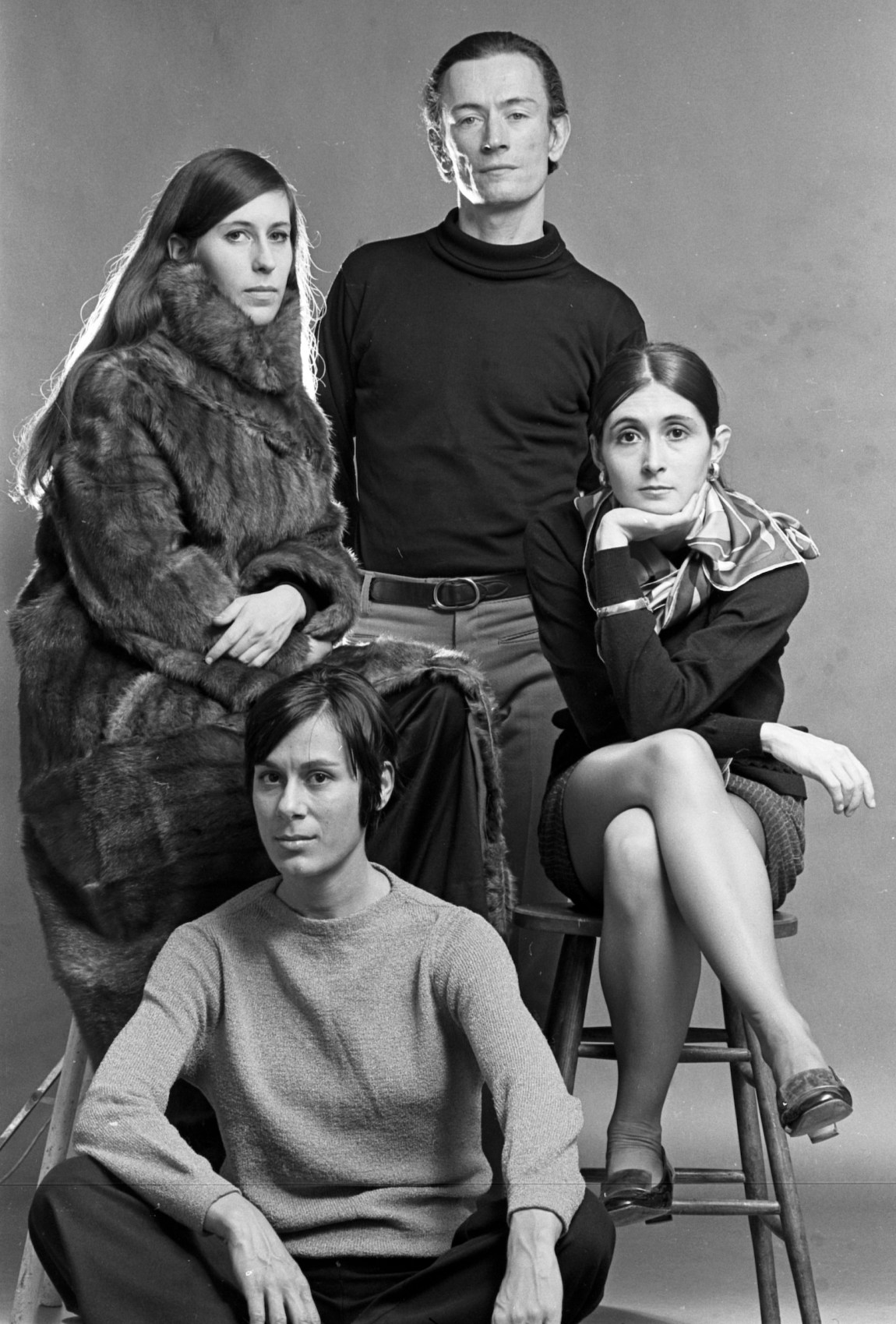

*

Monk formed her vocal ensemble in 1978 and shortly after signed with the Munich-based label ECM Records, whose director, Manfred Eicher, would become one of her greatest champions.6 What Eicher understood was her singularity as a composer, not just as a singer, performance artist, or choreographer. The title track of her first album for ECM, Dolmen Music (1981)—an intricate, cavernous setting for six voices (three male, three female) and cello, nearly twenty-four minutes long—revealed a compositional intelligence as formidable as that of her male peers, and in some ways more startling. (The interplay among the voices is so dense that it’s hard to believe there are only six of them.) Inspired by the Neolithic rocks Monk had seen in La Roche-aux-Fées, in Brittany, “Dolmen Music” ranges across a series of encounters and conversations between the singers, sometimes harmonizing, sometimes animatedly babbling like clerics arguing over the interpretation of scripture. Its plaintive, neo-Medieval sensibility has more in common with the “liturgical Minimalism” of the Estonian composer Arvo Pärt (another ECM artist, signed just a couple years before Monk) than with the downtown New York art scene.

As Eicher recognized, Monk’s music dissolves the usual markers of time, asking us to inhabit two temporal zones at once: an unspecified ancient past and a possible future, and to experience them as an absolute present. Or to put it in terms of space: it imagines where we’ve been and where we might be going. Monk is not unlike the heroine in Book of Days, a girl who lives in fourteenth-century Europe but has visions of planes and urban traffic. The ravages of the Black Death and antisemitism are real to the girl, but so are these hallucinations.7 The definition of a visionary, Monk reminds us, is the ability to see—or hear—a world beyond our own.

It’s tempting to divide Monk’s recordings for ECM by theme: explorations of female subjectivity (Dolmen Music, Do You Be); the apocalyptic pieces of the Eighties, responses to Reaganite militarism and the AIDS crisis (Turtle Dreams, Book of Days); the studies of personal and political mourning (mercy, impermanence); and the works of spiritual seeking and enlightenment (ATLAS, Songs of Ascension) or of environmental consciousness (Facing North, On Behalf of Nature, Cellular Songs). You could also divide them by instrumentation: the spare early works, in which Monk sings over a handful of minor chords on piano or electric organ; the choral pieces; the large-ensemble and operatic works; and the ballads and waltzes for solo piano.

Such classification has its uses, not least in underlining Monk’s expansiveness and constant searching. But a focus on her development risks concealing her music’s exceptional unity and cohesion. While the work has become bolder, and more elaborate in conception, the seeds were planted early: the whole has always been in the part. ATLAS’s depiction of a female visionary was prefigured, two decades earlier, by the Joan of Arc opera Vessel. The interwoven vocals of “Dolmen Music” and “Astronaut Anthem” look forward to the choral tapestries of Songs of Ascension several decades later. If the early chamber works possessed a mythic imagination, the later, large-ensemble works about human and natural survival have preserved a chamberlike, distinctively feminine sense of intimacy, making them feel less like grand statements than like conversations among a group of friends.

*

Fastidious and highly precise, especially in its use of rhythm, Monk’s music emerges out of slow, patient deliberation, sometimes for a period of years, followed by extensive rehearsals with her ensemble. (Experiences like the writing of “Do You Be,” which was conceived in a single day, are exceedingly rare.) Each live performance varies, but there is little room for individual improvisation. Nonetheless, improvisation and the ideas of the ensemble’s members help give shape to, and sometimes inspire, her writing. “Sometimes we will start with a very small cell,” the percussionist John Hollenbeck told me, “Then Meredith returns with a little more, and the piece grows with each segment. A year later you’re playing this piece, and you have no idea how it came together.”

Monk’s friend the composer Alvin Singleton once told her that he didn’t care who played his music, so long as it was played well. “I’m the opposite,” she says. In one of the most beautiful set pieces in ATLAS, “Choosing Companions,” the heroine, Alexandra, interviews a group of potential travel guides for her forthcoming expedition. Monk has exercised similar care in choosing companions.8 Like Duke Ellington—and, as Monk is quick to add, his arranger Billy Strayhorn—she writes specifically for the members of her ensemble, fellow travelers in music and movement.

The ensemble has been touring nearly as long as the Duke Ellington Orchestra did. Since its formation forty-five years ago, it has always been unusually diverse for a new music group: white, Black, Asian, Middle Eastern, Jewish, and Muslim, female and male, queer and straight. But the most enchanting thing about Monk’s ensemble isn’t its diversity but rather the joy they take in performing together. Her singers are never still when they sing (the “singing body” and “dancing voice” often invoked by Monk are not metaphors), and Monk herself often bobs and smiles, conveying the infectious sense that their “souls are touching.”

This moment is the gift of live performance, the “magic” for which Monk feels most grateful. But it can feel like a distant dream when she begins to write a new piece, and as she waits for inspiration to strike she often feels a kind of terror. Gradually, as she immerses herself in composing, the fear gives way to an intense absorption. “Curiosity,” she says, “is a great antidote to fear.”

The subject of fear inspired one of the few pieces Monk has ever written about a specific emotion. The words in “Scared Song,” on her 1987 album Do You Be, are not so much lyrics as sparse, nervous utterances (“Oh I’m scared/Oh she’s scared”) that name the condition being evoked by her otherwise wordless vocals. “Scared Song” has sometimes been misspelled as “Sacred Song.” This error is also an accidental illumination: the purpose of the sacred is, in part, to assuage our fears—of loss, of death, of the void—and channel them into a higher purpose. In this sense, much of Monk’s later music, particularly since her embrace of Buddhist practice in the mid-Eighties, can be characterized as sacred or devotional, although its spirit remains ecumenical and inviting. Aside from Alice Coltrane, no American composer of the last half century has produced such an imposing body of spiritual music.

In her “warning” pieces of the Seventies and Eighties, Monk highlighted the frightening undercurrents in modern society, especially the lure of totalitarian power and the threat of nuclear apocalypse. “But I began to wonder, how useful is this?” she recalls, “My listeners already know what the problem is. I decided that a more useful art would offer an alternative.” She wanted to transform performance into “a sacred space, in which audiences can let go of the discursive mind and experience something more directly…. What I basically want to do is make people look at their own lives, and maybe go out in the street and look and listen to things in a new way.”

Monk’s new direction was heralded by two works that celebrated the beauty and sacredness of everyday life: Facing North (1990), an album about the the still and snowy landscapes of Canada that she had witnessed on a residency in Banff; and ATLAS, the story of a spiritual quest that leads ultimately to the simple pleasures of a cup of coffee. The intensity of her early work has not vanished: Monk is too alert, too alive, not to register the dangers we face, especially from war and climate change, the subjects of mercy and On Behalf of Nature. Moreover, her music of recent years has become more, not less, formally complex, as Monk opened herself to what she calls the “rich possibilities of instruments as voices.” In large-ensemble works like Songs of Ascension, we are far from the Satie-like pentatonic harmonies of the Eighties. Her writing for clarinet, strings, and marimba has grown increasingly painterly, acquiring a sensuous and beguiling glow, and she has recently completed a haunting work for solo piano, “Dialogue,” full of pointillist detail and contrasts in dynamics, which is the closest she’s ever come to writing a sonata.

Even so, there is no doubt that her music today is more tranquil, as well as more explicit about its connection to healing and spiritual meditation. One reason for this is her relationship to Buddhism. (Monk keeps a picture of her teacher, Pema Chödrön, on her kitchen table in Tribeca.) But the shift in her music also reflects the impact of another life journey: her twenty-two-year relationship with the Dutch choreographer and therapist Mieke van Hoek, who died in 2002 at the age of fifty-six. Mieke, whose holistic, arts-based approach to therapy had many affinities with Monk’s aesthetic, brought her a sense of calm and peace that she had never known. At Mieke’s encouragement, they purchased land in New Mexico and built a small studio, which became Monk’s sanctuary. She fell in love with the Southwestern landscape, the inspiration for the pastoral and ecological themes of Songs of Ascension and On Behalf of Nature, late works of ravishing, celestial beauty.

In 2007, less than five years after Mieke’s death, Monk recorded the album impermanence. The first piece, “Last Song,” was written the year before Mieke died. Monk had been reading The Force of Character, by the Jungian philosopher James Hillman, in which he includes a list of “last” things (last chance, last dance, last minute, last laugh, and so on). Monk set Hillman’s list to a sorrowful piano motif, pronouncing the words, chanting them, then twisting them beyond recognition into the sound of lastness itself: the somber awareness of departure into another realm.

In its simplicity and directness, “Last Song” recalls Monk’s cathartic songs of the Seventies, “Gotham Lullaby” and “Do You Be.” When she finally recorded it, the song became a tribute to Mieke. Yet it was also something more. As devastating a loss as Mieke’s death had been, she says, her absence had also brought her closer to those who had known a similar bereavement. It had reacquainted her with music’s power to communicate with others about a shared experience, for a moment, in a world of impermanence.

“Meredith feels the loss and the grief,” John Luther Adams reflects, “but she already senses, and embodies, the possibility of redemption. In my own music, I’m trying to imagine a new culture that will rise from the rubble of this culture that seems to be crumbling already around us. Meredith lives there.” To listen to her music is to hope to join her one day.