Henry Hamlyn was a British wool merchant who lived during the first half of the sixteenth century. His house stood on a central street in Exeter, in Devonshire, in the southwest of England. Its façade was done in the half-timbered style common in French towns and cities like Morlaix, one of Exeter’s trading partners in the Brittany region. The house was leveled around 1840 to widen the road, and all that remains are sketches and three wooden posts that had been placed at street-level. Hamlyn had commissioned carvings of contemporary figures to adorn each post: a jester, his post topped with a shield depicting Exeter Castle; a peasant, topped with the Tudor crest; and a (possibly cuckolded) man being knocked about by his buxom wife, topped, perhaps as a wry joke about Hamlyn’s domestic situation, with a shield monogrammed with his initials.

The faces are remarkably expressive. The peasant glowers downward, frown lines deep and articulated. The jester’s upper lip recedes to expose his teeth; his pupils are blank, and he holds a staff topped with an eerie miniature of his own face. A codpiece pokes out from his overcoat. The quarreling couple was an archetypal illustration of the late Middle Ages, appearing on decorative plates and engravings; the typical formula showed a woman with a stereotypically matronly frame physically dominating her husband with something like a wooden club, often tenderizing his exposed ass. On Hamlyn’s post, we have a frontal view (no indication of yanked trousers) of one such a matron raising her club over her husband’s head, which she holds by the hair. Whatever imperfections have been cleaved into the wood by time only deepen the weariness on each craggy face.

It’s a shame that the craftsman responsible for these carvings is unknown, but anonymity is woven into the fabric of “Rich Man, Poor Man: Art, Class, and Commerce in a Late Medieval Town,” an exhibition at the Met Cloisters that draws us into close quarters with Hamlyn, one man whose name we do know. The show makes use of the historical method known as microhistory, which can be applied both to objects and to episodes from the lives of individuals, often common or unremarkable people. Probably the two best-known examples are Carlo Ginzburg’s The Cheese and the Worms (1976) and the late Natalie Zemon Davis’s The Return of Martin Guerre (1983).1 Ginzburg’s book takes as its subject Menocchio, a charismatic sixteenth-century Italian miller who proselytized a unique theology (or, to some, heresy) at his local tavern until the Inquisition caught up with him. Zemon Davis’s book is about an impostor in the same century: eight years after a man named Martin Guerre abandoned his life in a small French village, another man turned up, claiming to be him.

Both books rely in large part on court cases, not just because of their inherent drama but because trials entail paperwork—records of what people said, and by extension how they thought and spoke. Unfortunately, Hamlyn appears to have been law-abiding. All the same, the show’s curator, Melanie Holcomb, also found the germ for “Rich Man, Poor Man” in official documents. In 1974 the Met acquired the three wooden posts from the descendants of the last owners of the building, which had been converted into a tavern around 1700. Holcomb told me she initially imagined including the sculptures in a jolly exhibition about medieval drinking culture. Her plan changed when Hamlyn’s initials caught her eye and sent her rifling through Exeter tax records, where she found her man.

The show is small, but makes a relatively big argument: that there was a newly established “middle class” during the period generally called the late Middle Ages, and that the daily life of those who were a part of it can be understood by studying Hamlyn’s world. The posts are the only artifacts on display that belonged to Hamlyn himself. The rest are objects of the kind that might have belonged to others in his milieu, such as a tankard made of silver and serpentine, gold rings, and a brown wool knit cap from the sixteenth century, which floats unassumingly on a short hat stand, making the ghostly suggestion of Hamlyn underneath.

*

Wool was at the center of European trade in the late Middle Ages: it funded wars and in one instance paid the ransom of a king. By some estimates, at the height of the commodity boom, England was a country of 12 million sheep. The 1353 Ordinance of the Staple, which in part served to regulate port cities, called wool “the sovereign merchandise and jewel of this realm of England.”

In a catalog essay for “Medieval Money, Merchants, and Morality,” a new show at the Morgan Library and Museum, the historian Steven A. Epstein estimates that 80 percent of Europe’s population was working in agriculture by 1500, and that it took about four farmers to produce enough food for a single person. “European agriculture must have been remarkably inefficient,” he writes, “to require such a massive commitment in the labor force.” The production of wool was likewise a laborious ordeal that answered increasingly high demand from a European market, which is where merchants made their money.

Advertisement

Sheep are relatively low-maintenance, really needing only a long grazing season to maintain a steady output. To produce a textile suitable for cloth markets on the continent, the raw wool fresh off the sheep’s back was sorted by fiber coarseness, brushed out, and then washed. Once woven, the cloth would be placed in a barrel with an astringent solution, often urine, and agitated with one’s feet. This process would eventually be improved and streamlined: in his excellent book An Economic and Social History of Later Medieval Europe, 1000–1500, Epstein credits the “generations of endless tinkerers” who contributed innovations such as fulling mills (which took the feet out of the process), spinning wheels, and looms.2 After washing, the cloth was essentially ready to be sold to merchants, who then sold it for a profit to clothing manufacturers in places like Flanders and Italy.

The English merchant class that Hamlyn belonged to had established itself across Europe by the time of his family’s rise in Exeter. (The History of the Suburbs of Exeter, published by a man named Charles Worthy in 1892, touches briefly on “those [Hamlyns] of Exeter,” who “in the course of years, prospered in mercantile pursuits and gave mayors to that city, and filled other municipal offices.”) It is impossible to speak about this merchant class without speaking about the institution of guilds, which during this period were numerous and common. As Epstein writes, “in no two places were their growth and roles really the same.” Often, he argues, a guild was effectively a confraternity, “in the sense that its members, bound by a common oath and faith…worshipped together in their chapel, buried their members, and spiritually bonded as a group who happened to be in the same trade.”

For over thirty years Hamlyn belonged to an association that seems to have served some similar functions, Exeter’s city council, whose members were mostly merchants and other men of status. The show doesn’t address this group’s spiritual life, but it fills in a picture of Hamlyn’s surroundings by imagining the council as a dignified and matey band of brothers. One item on display is a key to a strongbox containing sensitive documents. Such a key might have belonged to one of Hamlyn’s fellow councilmembers, who would have shared copies of the key with his colleagues in case anything happened to him. The suggestion is that these were wealthy, self-made men who created a social world based on shared values and power.

*

Entering “Rich Man, Poor Man,” one is greeted by Man Weighing Gold (circa 1515–1520), a portrait by Adriaen Isenbrant. It depicts an unidentified merchant clothed soberly in what the label notes are the garments mandated by law for his profession, save for touches of luxury—a fur stole and a winking peek of crimson fabric at his chest. His measured countenance is staid. At the Morgan show, in the dynamic Portrait of a Merchant (circa 1530) by Jan Gossart, the subject stares down over a haughtily raised jaw, a ledger in front of him to signal the day’s hard work, beside which a small pile of coins indicate modest wealth. As one of the show’s curators, Diane Wolfthal, argues in the catalog, such portraits are inflected with the anxiety merchants felt about their position. Motifs like the ledger and coins distinguish a sitter from the leisured nobility, instead depicting them as serious about their work, deserving of their income.

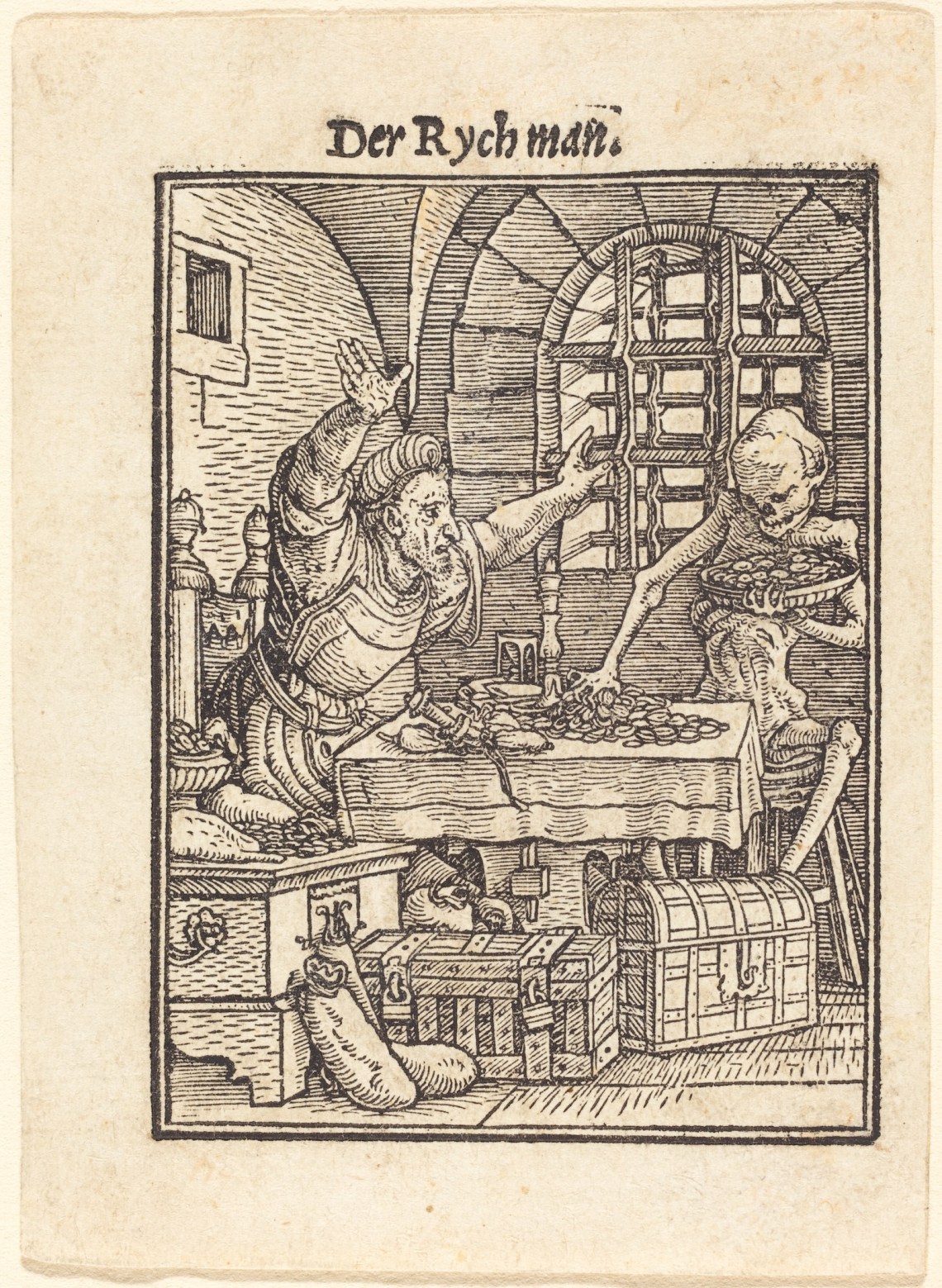

In Hieronymus Bosch’s Death and the Miser (1485–1490), money is what will decide between salvation and damnation during a man’s final moments. The painted panel depicts skull-headed Death coming through the door for a man on his deathbed, who raises one hand toward a beam of light shining from a window adorned with a crucifix, and reaches the other downward toward a demon handing up a sack of money. It’s an almost literal confrontation with the question on the show’s wall text: “Your Money or Your Eternal Life?” (The organization of this exhibition can be befuddling in its thematic overlap. Both wall text and smaller labels repeat as categories phrases such as “Moral Responses to Money,” “Immoral Ways to Earn and Spend Money,” and “Will Money Damn Your Soul?” but the distinctions among them are vague.) Much of the show consists of a dizzyingly expansive assortment of illuminated manuscripts, which support every aspect of the exhibition, from a brief history of coinage to antisemitic attitudes about money to, most vividly, the Christian’s moral wresting with the concept of wealth. We are reminded throughout that Judas betrayed Christ for thirty pieces of silver.

Advertisement

Both exhibitions suggest that the new merchant class went through a period of fraught moral development as its relationship to money and accumulated wealth changed. The emphasis uptown is social: the Cloisters show is concerned with what happens when a society develops a new class hierarchy. The one in Midtown is spiritual: how individuals perceive the metaphysical implications of wealth. Wolfthal quotes Thomas Aquinas: “by riches man acquires the means of committing any sin whatever.” In his theology, Aquinas also drew a distinction between natural and artificial wealth. The former is the kind of abundance that sustains life—livestock, comfortable shelter, land for your family. The latter is abstracted from any natural means of sustenance—in other words, money. The merchant found himself in a penumbral space between the two, springing from one into the other.

Neither show is interested in defining the merchant class in systemic terms—say, by tracing the ascent of modern capitalism around the world during this period. Instead both exhibitions define their subject in relation to the peasant class below it. “Medieval Merchants” is indirect about this, its subject being the inward-facing guilt that only implies comparison to the poor. “Rich Man, Poor Man,” on the other hand, prominently features engravings by Albrecht Dürer and Sebald Beham, a prolific German artist who depicted peasant life, often on a small scale. Viciously animated, his work plays into the same ribald peasant stereotypes as Hamlyn’s wooden posts. As the wall text suggests, we’re left wondering who the pictures are for, who is and is not let in on the joke. Beham’s Head of a Man (1549), a relatively stately anonymous portrait included in the first months of the exhibition’s run (and since taken down due to light sensitivity), serves as a foil to the paintings of merchants. A peasant is presented in profile, tongue cheekily stuck out at the viewer, a glimmer of more knowing self-awareness.

At the Hamlyn show, there are no apparent hang-ups about the sumptuousness of new money and what it could afford. The items on view are simply to be admired, such as gorgeous blue-and-cream textiles from Perugia and pieces of silver crockery that a merchant would have bought to entertain guests in his home. Among the most evocative of these objects are intricately decorated trenchers: small dessert plates that were to be flipped over once the sweets served on them had been eaten. The verses on the other side were meant to be read aloud by guests for after-dinner amusement. On the back of one:

And he that reads this verse even now,

May hap[pen] to have a loving sow:

Whose looks are nothing liked so bad

As is her tongue to make him mad.

And on another:

Ask thou thy wife if she can tell,

Whether thou in marriage hast speed well

And let her speak as she doth know,

For 20 pounds she will say no.

Displayed in the last room of the exhibition, the hypothetical inner sanctum of Hamlyn’s home, these trenchers act as bookends to the pilons that open the show—vignettes of daily life to be enjoyed not by passersby but by guests. And compared to the engravings by Beham and Dürer, the humor is tempered by something slightly wittier than bawdiness. The third one reads:

If thou be young, then marry not yet,

If thou be old, thou hast more wit:

For young men’s wives will not be taught,

And old men’s wives be good for naught.

It’s easy to forget that these things did not all belong to a single person. That’s to the credit of the show; the pieces have been arranged so that you start to locate and fill in gaps without being told much at all about Henry Hamlyn, who becomes a pretty solid silhouette, if not a full portrait. With his fine crockery and his potentially offensive beams and his council, he is ultimately not a very sympathetic character. The Morgan show never attempts to find its way into any one life, and its interest is not in microhistory but in a more traditional form of historical inquiry that attempts to draw broader conclusions about a period, a place, and its people. But that approach still lets the show speak with a certain authority about the inner life of the merchants of the time and the intimations of damnation they might have felt. Like its counterpart at the Cloisters, it leaves you with a sense of uncanny recognition, of what Henry James called “a palpable imaginable visitable past.”