When I heard about the death of the Los Angeles–based artist Alexis Smith, who was done in after a nine-year struggle with Alzheimer’s disease on the second day of the new year at the age of seventy-four, a blunt phrase by her favorite writer, the noir novelist Raymond Chandler, echoed my sense of loss: “I felt like an amputated leg.” The news shook me not only because Alex, as she preferred to be called, was an old friend and just a year younger than I. That malady is always a nightmare, but it struck me as an especially cruel fate for one of the smartest creative figures of her generation. Smith was among the most perceptive and knowing decipherers of our country’s character, which she demonstrated across five decades of making witty, strange, poignant, and oddly beautiful assemblages of everything from lurid grindhouse movie posters and inept flea market canvases by amateur painters to weathered roadside signage and once-cherished religious talismans. These irreverent but subliminally logical mashups became her signature medium, allowing her to comment with rare acuity on everything from consumerism and sex to patriotism and the natural environment.

Smith was wholly accepting of both the deep-seated venality and irrepressible optimism of the American Dream, and remarkably understanding of her fellow countrymen and their unquenchable lust for fame and above all fortune. In the catalogue for An Embarrassment of Riches, a 2001 New York gallery exhibition of Smith’s work, the poet Amy Gerstler called the show a “rather non-judgmental critique of current materialistic American culture.” That assessment could apply equally to Smith’s entire output.

Smith’s work often makes you smile. Her 1982 mixed-media collage Bombshell features a rectangular silver platter on which a silhouetted black cutout of a curvaceous female torso is topped with a lifelike pair of plastic fried eggs in place of breasts, with a lacy white paper doily encircling lower regions. But her art also makes you think long after initial amusement fades, in this instance about women being served up for the delectation of men. Her oeuvre addressed nearly every way that women are perceived in our society, demonstrated by her 1985 LA gallery show Jane, which probed the coded messages conveyed by real and fictional bearers of that name, such as Jane Austen, Jane Eyre, Calamity Jane, Jayne Mansfield, Tarzan’s mate, the little girl from the Dick and Jane reading primers, and Jane Doe.

Smith’s forays into this terrain ranged from gendered middle-class rituals, such as the crowning of a Suzy Creamcheese prom queen in a work called White Christmas, to taboo subjects like underage sex. (A piece titled Jailbait is captioned “Oh, man, she was only fifteen and wearing jeans and waiting for someone to pick her up.”) In addition to the home in its many manifestations, her favorite themes included Hollywood stereotypes of femininity (a super-scale Warholesque wall painting of Marilyn Monroe’s head, with eyewear reflecting football players in mid-play, is named Men Seldom Make Passes at Girls Who Wear Glasses) and the manipulative conventions of eroticized advertising (an assertively seductive image of a phallic Chiquita Banana is captioned “SOMETIMES MEN WENT CRAZY FROM THE HEAT”).

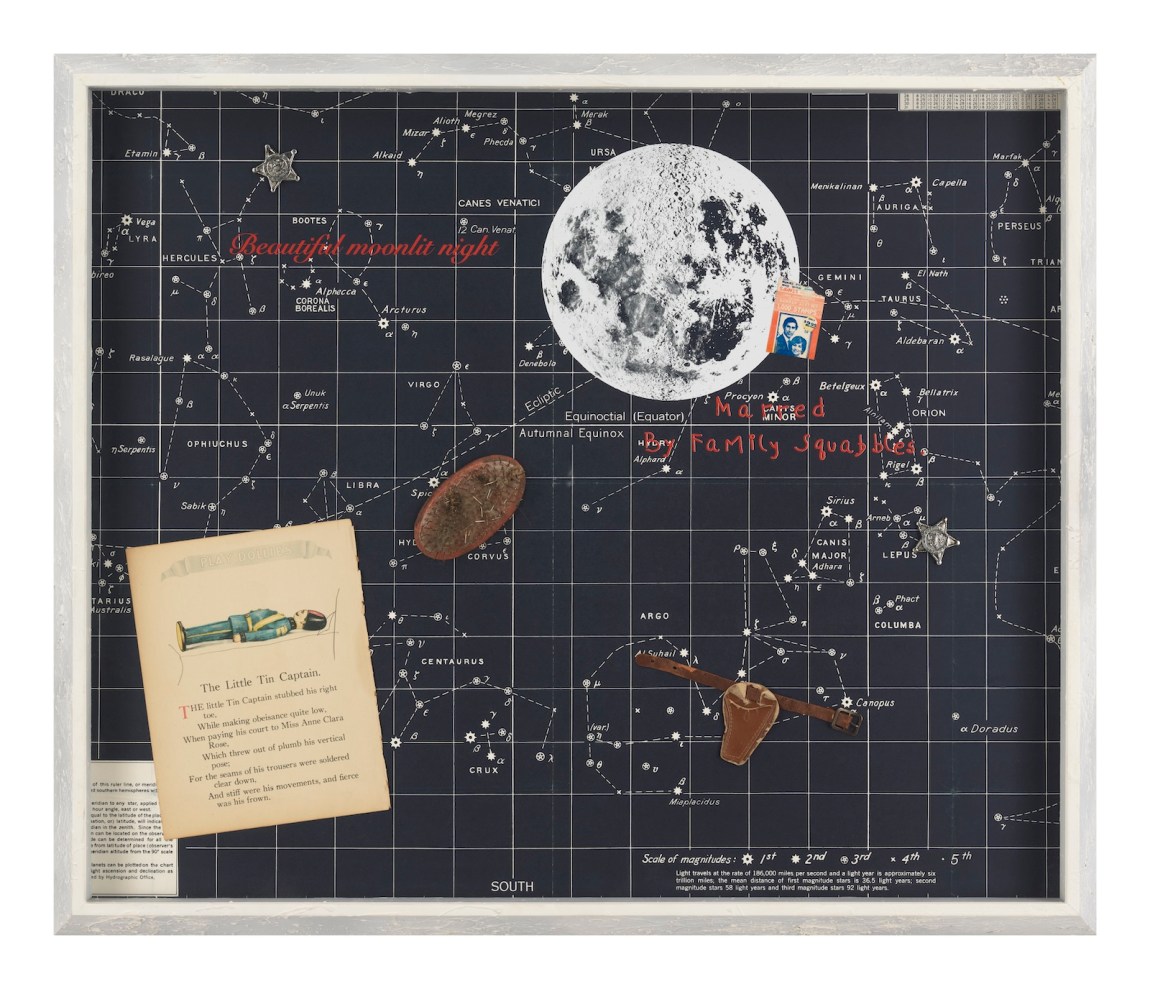

Other contemporary women artists have made provocative use of words in their more sleekly presented constructs, among them Barbara Kruger, with her room-sized black-white-and-red-all-over installations (“Your body is a battleground” and “I shop therefore I am”), and Jenny Holzer, with her mesmerizingly impersonal LED signs (“PROTECT ME FROM WHAT I WANT” and “MONEY CREATES TASTE”). Smith, however, loved not only demotic American speech but also the physical detritus of our throwaway culture. She often incorporated found objects into her compositions, starting with her earliest works, which included typewritten texts on individual sheets of office paper to which she affixed tiny Cracker Jack toys. She haunted yard sales, thrift shops, and swap meets in search of castoff items that would add texture and authenticity to her assemblages. In time her friends and fans joined the hunt for just the right weird thing that might appeal to her.

*

She was born Patricia Anne Smith in Los Angeles in 1949. Her psychiatrist father, Dayrel Driver Smith, worked at a state mental hospital in Norwalk, to the east of the metropolis, where the family lived on the institution’s grounds. Her mother, Lucille Doak Smith, a homemaker, was plagued by illness and left childrearing largely to her husband. She died when Patti, an only child, was eleven. “It was a huge accidental boon that I was raised by my father,” Smith told Hunter Drohojowska-Philp for an Archives of American Art oral history in 2014. “Because my father didn’t know how to raise me as a girl. He only knew how to raise me, like, as a guy.” He also instilled in her the self-confidence that often arises when a father gives support to a daughter. That gender-blind upbringing imparted a tomboyish quality that made her the art world version of Katharine Hepburn, minus the annoying accent and insufferable egotism, with a dash of Quentin Tarantino thrown in.

Advertisement

After graduating from Whittier High School in 1966—her father moved the two of them to Richard Nixon’s whitebread hometown after his wife’s death—she enrolled at the University of California branch that had opened just the year before in nearby Orange County. She later insisted that “the most propitious decision I ever made in my entire life was to go to Irvine.” After abandoning her original intention to study French, she was drawn to Irvine’s first-rate art program, where her teachers included Robert Irwin, Vija Celmins, Larry Bell, and Bruce Nauman. “As everyone sort of famously knows,” she reminisced, “I dated my professors and was completely sucked in by them and their lifestyles…. And it wasn’t some kind of big scandal or whatever. It was just a different world.”

While in college she adopted a new first name, Alexis (she never changed it legally), favoring the androgynous quality of the nickname Alex and seeing it as necessary part of her self-reinvention as an artist. Only afterward did she discover there was a second-tier movie star from the Golden Age of Hollywood also called Alexis Smith, but that simply added to the glamour of her new incarnation. In her interview with Drohojowska-Philp she remembered the actress’s reaction to this unauthorized appropriation: “Her husband, Craig Stevens, was mad at me forever, although she was very nice about it.” Had she not changed her name, however, the artist would have been known as Patti Smith.

Before Smith found an early believer in the LA gallerist Riko Mizuno, she worked to make ends meet in Frank Gehry’s Santa Monica office. It was through Smith’s job there that my wife, the architectural historian Rosemarie Haag Bletter, and I first met her in the mid-1970s, two decades before Gehry became the world’s most celebrated architect. She was the firm’s “girl Friday,” pursuing a host of miscellaneous tasks, but one aspect of her boss’s modus operandi particularly impressed her. She noted that Gehry and his collaborators, experimenting with highly irregular forms not often seen in architecture, would create cardboard models of structures that they had no idea could actually be built:

They’d already signed the contracts by the time they were, like, trying to figure out how the heck they were going to do it…. Because that’s the secret. The secret is to say you can do it, even if you don’t know how to do it. Right? That’s like the magic key.

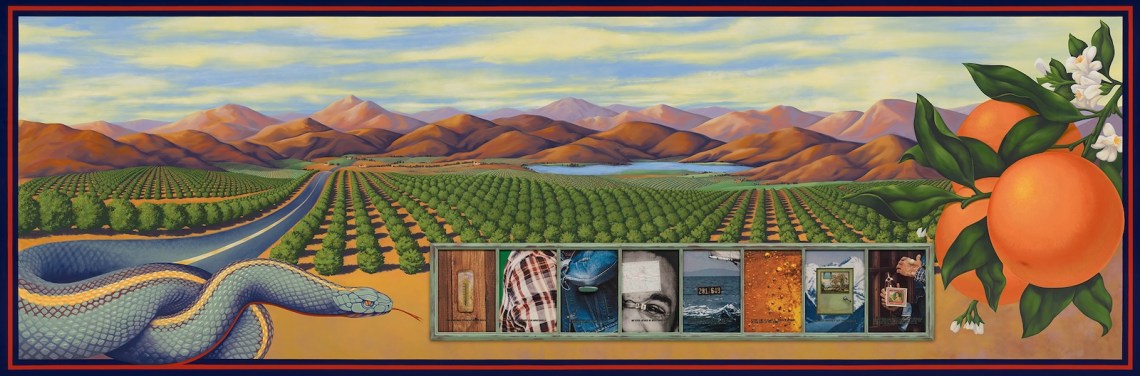

Years later Gehry’s chutzpah emboldened her to undertake large-scale public commissions without having had any prior experience. Among them was Snake Path (1992), a 560-foot-long slate-and-concrete mosaic walkway in the shape of a gigantic serpent on the UC San Diego campus in La Jolla.

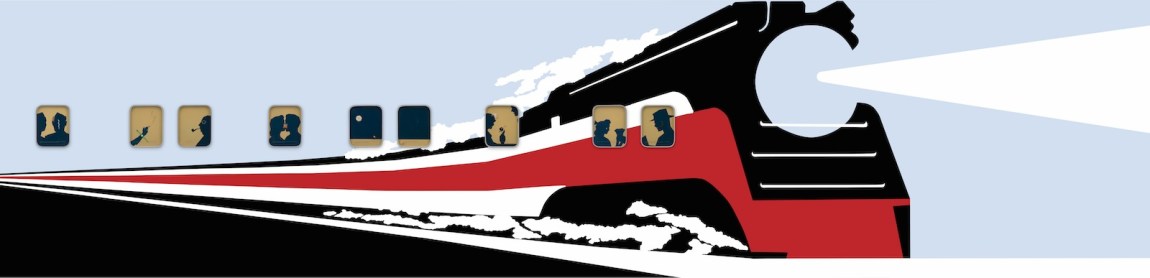

Smith’s increasing ambition was signaled by her progression from multi-page typewritten-and-collaged sequences to room-sized installations like Raymond Chandler’s LA (1980), exhibited at that city’s Rosamund Felsen Gallery. That show, in the spirit of her previous work, incorporated texts taken from the crime author’s now esteemed pulp fiction. But this time she also painted the walls of the display spaces with the silhouettes of low-rent cityscapes akin to Chandler’s nocturnal realm of private dicks, dangerous dames, and the saps who fell for them. In 1977 she was taken on by the pioneering SoHo dealer Holly Solomon, who gave Smith her first solo New York gallery show, after which we began to see more of each other on both coasts. The Holly Solomon Gallery roster was dominated by the leading exponents of the Pattern and Decoration movement (a gleefully superficial reaction against dour Seventies minimalism), but it also gave important early exposure to very different artists including Nam June Paik, Gordon Matta-Clark, William Wegman, and Robert Mapplethorpe. Alexis Smith began to be considered more than just an LA artist.

*

In 1980, a year after I became an editor at Condé Nast’s House & Garden magazine, I asked Smith to create one of her installations for publication, stipulating only that it express some domestic theme. At that time, House & Garden maintained a spacious photo studio where a team of skilled artisan-craftsmen—adept at carpentry, painting, wallpapering, upholstery, and furniture refinishing—would conjure up lifelike vignettes and full-scale room mock-ups so that we could editorially feature advertisers’ home furnishing products if they didn’t appear in the private residences we published. When I offered Alex the studio’s services for a week, she eagerly accepted, and began sketching a work called New World.

Advertisement

Intrigued by notions of point perspective, she came up with an illusionistic scheme that, when seen in a fixed position from a tripod camera’s viewfinder, would show a traditional American living room—she chose a generic camelback sofa, a pair of Chippendale wing chairs, coffee table, and chimneypiece—superimposed with a silhouetted map of the Western Hemisphere. However, closer inspection revealed that matching brown fabric and wallpaper in a tiny floral pattern was actually applied to the furniture, floor, walls, curtains, and ceiling to read as North and South America, but only when seen from that single vantage point. If you moved around the space, the effect would be entirely lost. The studio staff was initially baffled by this bizarre assignment, but Alex engaged them so effortlessly that soon they were thrilled to be executing a genuine artwork. The finished product ran in the February 1981 issue and was pure Alexis Smith—at once simple and complex, playful and serious.

The pinnacle of her career came with her 1991 retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art, curated by her longtime advocate Richard Armstrong. But although the show garnered excellent reviews and later travelled to LA’s Museum of Contemporary Art, it seemed to be an equivalent of the alleged Oscar Curse, whereby winners of the Academy Award subsequently experience an inexplicable hiring slump. In 2004, she confided to me, a New York gallery exhibition of her recent work sold not a single piece. She was, however, immune to peer envy and blithely unconcerned about her critical standing or earning power. As she commented to Richard Hertz for his 2009 book The Beat and the Buzz: Inside the L.A. Art World, “I don’t necessarily see retrospective number two in my immediate future.” (She actually received another, Alexis Smith: The American Way, which opened at the Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego in 2022.)

I believe that there’s another kind of work that is popular now, more abstract, imagistic. Today there’s a cooler, sleeker brand of art. I’m into the found object, the detritus of the world. In the current art world, I’m not sure detritus is particularly popular except as something to riff on.

Resigned to being out of fashion, she was content with her status as an outlier on the order of Joseph Cornell, her closest spiritual antecedent, who was likewise beguiled by movie stars, magic, the cosmos, found objects, and juxtapositions of the cozily familiar and the unsettlingly surreal.

In 2003 I asked Alex if she could create a work that would be a present to Rosemarie for our twenty-fifth wedding anniversary, and of course offered to pay her. She agreed, but with the proviso that she do it free of charge because of a bad experience in which the collectors who commissioned a similar piece hated the result. Their friendship never recovered, which she didn’t want to risk with us. She needn’t have worried, since my wife and I loved the final product, a mixed media collage nearly twenty inches square, titled Attachment.

The composition is centered by a quartet of rectilinear Bauhaus-style chromatic charts comprised of small, multicolored squares, an allusion to Rosemarie’s scholarly interest in the Weimar period art-and-design school. Surrounding it is a wide border of homey brown-and-white gingham checked fabric, in turn a reference to my three decades of editorial work for shelter magazines. At the very center, superimposed on the Modernist mosaic, are two conjoined lengths of brown homespun cord, a nod to “tying the knot.” She chose a maple Biedermeier style frame with small corner squares—Smith considered framing integral to her art and preferred not to leave it to others—that adds a final touch of bourgeois familiarity to this very personal evocation of our marriage.

In 1990 Alex married Scott Grieger, a mild-mannered artist and professor in the circle of the maverick art critic Dave Hickey. Scott clearly adored Alex, and her friends found him a welcome contrast to the bad boys to whom she had repeatedly been drawn. (Among them was the late conceptual and performance artist Chris Burden, best remembered for gruesome self-mutilations such as crawling through broken glass, being shot on video by a low-caliber rifle, and being crucified atop a Volkswagen Beetle.) Alex and Scott settled into happy domesticity in a charming bungalow on a quiet street in the Venice section of LA, a fitting final destination for this great celebrant of the atavistic comforts and persistent myths of home.

After the turn of the millennium, Smith told Hertz, she was no longer as driven as she once was: “I don’t have the same burning desire to be everywhere and do everything and see everything.” To her surprise she was so inspired by her husband’s pedagogy that she began teaching night school at LA’s Otis College of Art and Design, where he was on the faculty. “Scott has always had the idea of art as a cultural activity, something everybody can do at his or her own level, that art isn’t only about becoming famous,” she added. “When we got married I was a hard ass. I thought, ‘Who cares about those people who can’t be real artists?’ Now I’ve gone the other way, back to ‘I can make anybody better, I just can’t make them great.’” Only herself.