Many hardworking artists toil at the lowest rungs of their profession their entire careers, and many great successes would have stayed there had it not been for a lucky break. For the British pop band Wham!, that break was a slot on the Top 40 show Top of the Pops in the fall of 1982. Their second single, “Young Guns (Go for It!),” had stalled at forty-two on the charts, but when another band couldn’t make their booking, “we got this miracle phone call out of the blue.”

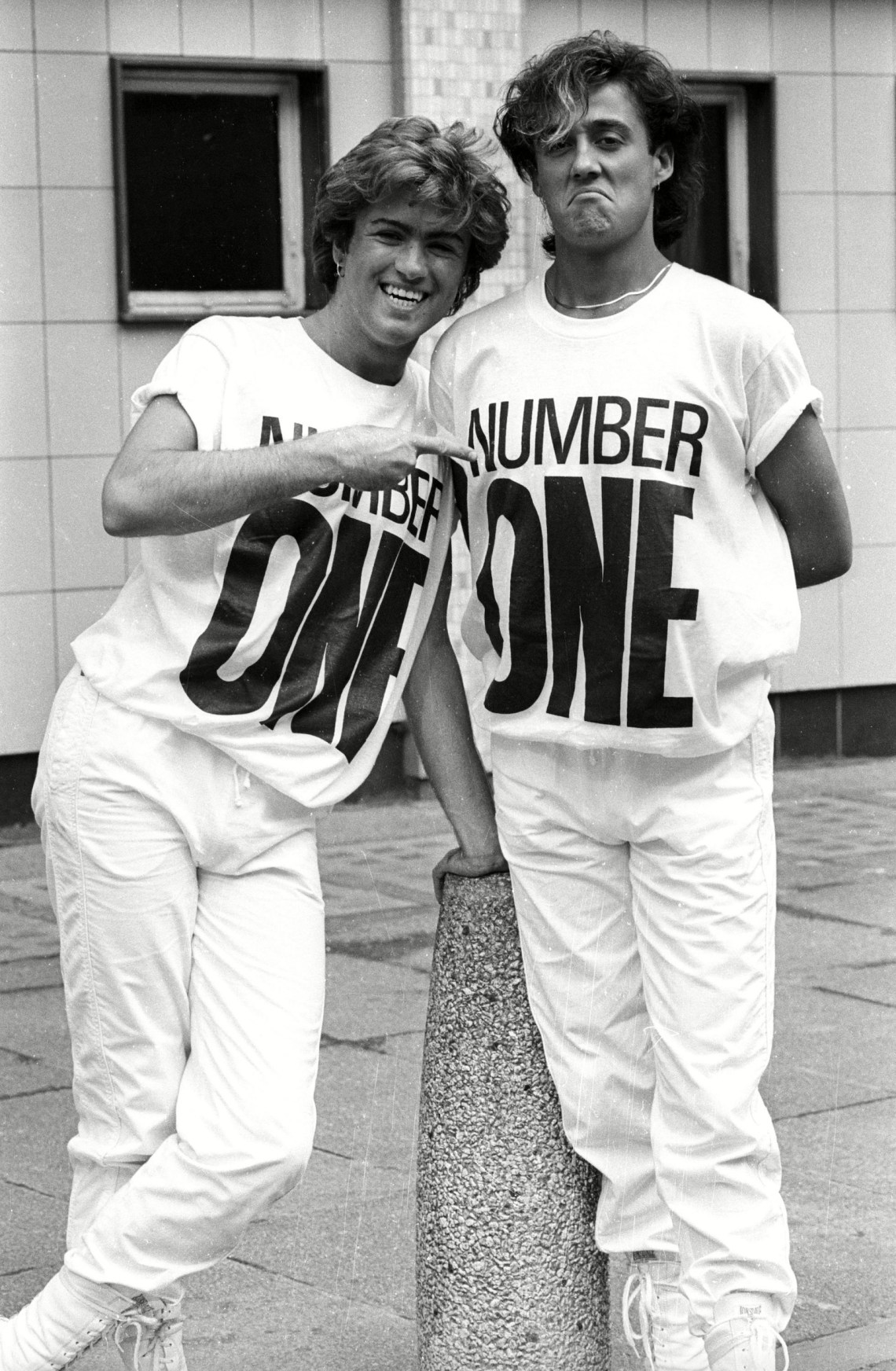

The duo met in 1975 when they were both twelve, after Andrew Ridgeley raised his hand on the first day of school and volunteered to look after the new boy, Georgios Kyriacos Panayiotou, whom Ridgeley promptly renamed “Yog.” Born in England, the descendant of Cypriot shepherds, Yog was, by his own description, a “very awkward, slightly porky, very strange-looking bloke . . . and quite shy.” Both boys had English mothers and immigrant fathers; Ridgeley’s father was an Alexandrian Jew who left Egypt at the time of the Suez Crisis.

In 1979 Ridgeley, Panayiotou, and some neighborhood pals formed a ska band called The Executive, which quickly fizzled out, though not before recording a jaunty two-tone cover of Beethoven’s “Für Elise.” The duo kept writing music together and gave their new group the name Wham! After Ridgeley pressed their demo tape into a reluctant executive’s hands at a pub in Hertfordshire, they signed a deal with the independent label Innervisions in February 1982. Their first single was a catchy synth-brass trifle called “Wham Rap! (Enjoy What You Do)” that drew on several emerging sampling-and-sequencing genres without landing clearly in any of them. Its pattery lyrics invoked the angry young men of Thatcherite England; its video aimed to evoke the grit of Brixton but instead landed somewhere closer to West Side Story. “Sounds described us as ‘socially aware funk,’” Ridgeley wryly recalled. The first pressings of the song were credited to “Panos/Ridgeley”; shortly afterward, Yog adopted the stage name George Michael.

“Wham Rap!” failed to crack the Top 100. “We were under massive pressure to chart,” Ridgeley remembers in Wham!, a new documentary about the band out on Netflix. “If ‘Young Guns’ wasn’t a hit we would be dropped.” “Young Guns” was a more focused slice of post-disco pop, one part Human League and one part Donna Summer. Fortunately, their slapped-together outfits and slouching but determined moxie resonated with Top of the Pops viewers. “It all happened so naturally—and that’s why I think it worked,” reported Shirley Holliman, a childhood friend and unofficial band member who performed with them that night. The single shot to number 3 on the UK singles chart; on the back of its success, “Wham Rap!” went to number 8.

Despite his cynicism about listeners’ taste and his understanding of the industry’s sausage-making machinery, Michael, who died in 2016 of heart failure at the age of fifty-three, regarded chart placement as the ultimate test of success. For most of his career, he made decisions calculated to ensure it. On the first page of his early-career memoir Bare (1990), the book’s coauthor, Tony Parsons, describes him as “someone who spent most of his time between the ages of seventeen and twenty-six trying to be the biggest act in the world.”

Michael’s writing—and ambition—quickly outpaced Ridgeley’s. “The goals that we . . . set ourselves could only be attained [with the] quality of songwriting that he was able to produce,” the guitarist admits in Wham! Soon Michael wasn’t just the band’s lead singer and primary songwriter; with remarkable confidence and speed, he also took control of its image, release schedule, and sound. The light overtone of social commentary quickly vanished.

A draft of Wham!’s global hit “Careless Whisper” had been on the demo tape that first caught Innvervision’s attention. Once they got a record deal, they cut a proper demo (“with a band and a sax and everything,” Michael told Parsons), but the song didn’t make their debut LP, Fantastic (1983). After disputes with the label the band decamped to Epic Records for their second album. Michael traveled to Sheffield, Alabama, to lay down the track with the legendary Muscle Shoals Rhythm Section under the direction of the equally legendary producer Jerry Wexler, the man who coined the term “rhythm and blues” back when he was a music critic at Billboard. “I would stand there, ready to [sing],” Michael recalled, “and Jerry would say, ‘Remember George, that’s where Aretha Franklin sang ‘Respect.’” Michael was dissatisfied with the results of the sessions, and by the time he returned to London he had decided to rerecord the song and produce it himself. “George went through ten sax players before Steve Gregory came in and nailed the part,” says Ridgeley.

Advertisement

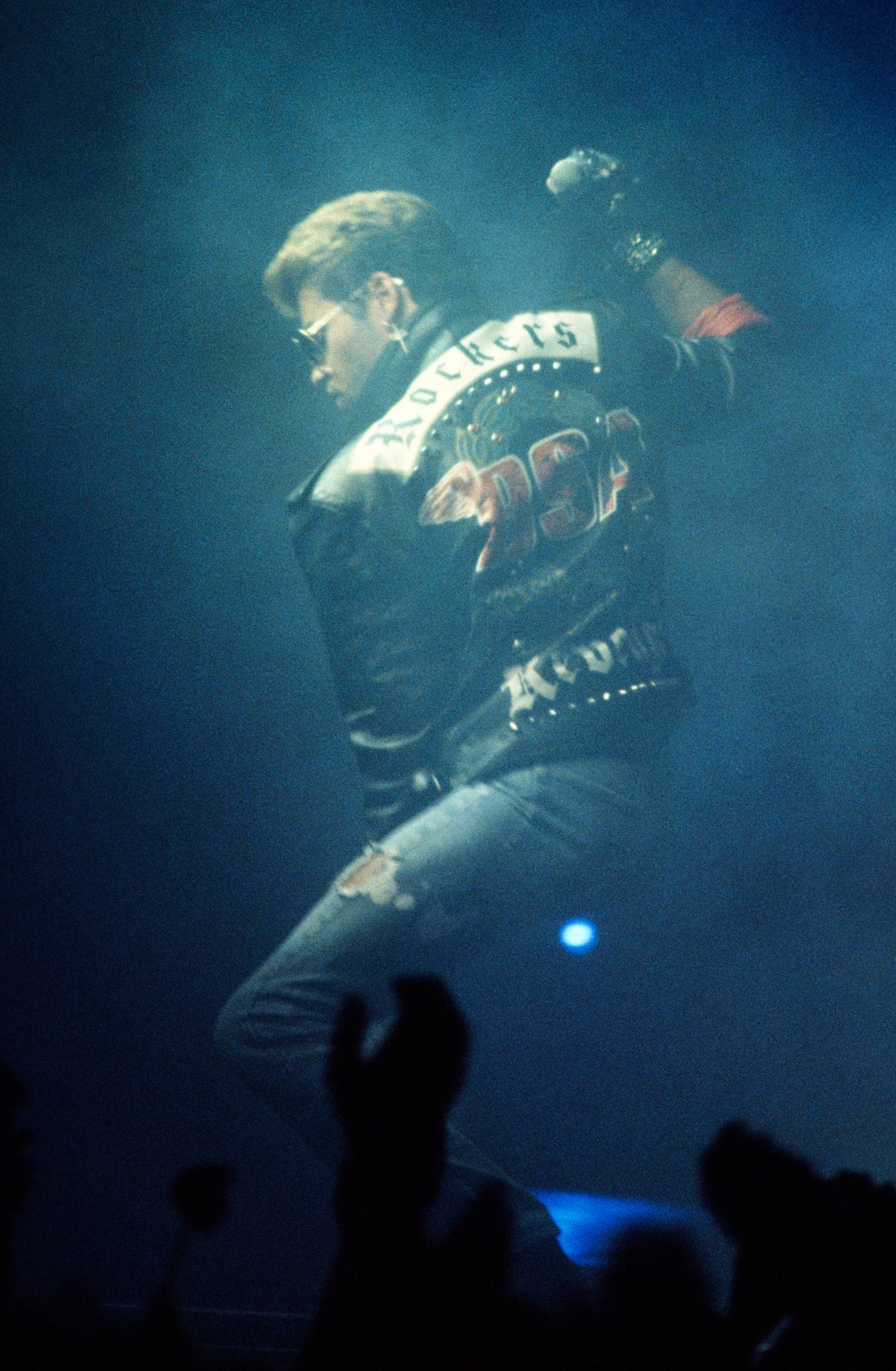

The London studio version was the second single from 1984’s Make It Big. Armed with a quite literally unforgettable saxophone solo, that summer it went to number 1 in ten countries, including the United States. Michael was twenty-one years old. After that, the label’s approach changed abruptly. On the first album Michael hadn’t been allowed to produce. Now, he remembers in Wham!, “it was suddenly, ‘You gotta produce it yourself.’” From then on he would produce or coproduce all his material. “I knew how to make these records,” he said in Freedom Uncut (2017), a documentary about his career that he directed just before his death, “and how to make them jump out of the radio.”

Michael is best known as a singer and widely recognized as a songwriter, but his greatest skill may have been production. The acoustic guitar that opens his 1987 solo single “Faith” hovers with perfect clarity just the right distance from the listener’s ear, as if the guitar player was strumming just a few feet away; in a decade practically synonymous with stiff, booming percussion, his drum programming has a deft, humorous touch that verges on virtuosity. “I’m a producer before I’m a singer sometimes,” he says in Wham! “I construct what I do.” Michael had the commercial aspirations of a global superstar like Madonna, but he also had a perfectionist streak more befitting a chart eccentric like Kate Bush. In the thirty years between his first solo single in 1986 and his death in 2016, he released only five studio albums, one of them a covers album. In the same span Madonna released eleven, David Bowie ten, and Prince thirty-one. (Bush also released five albums of studio material in that period, one of them a covers album—of her own songs.)

In 1993 Michael performed with the surviving members of Queen at the Wembley Stadium tribute concert for Freddie Mercury. “I just wanted perfection,” he reminisced, “which is what I always want.” To rehearse, “everyone else went for an afternoon. I went for five days. Because it had to be perfect.”

*

Pre-Internet music charts were determined by sales at particular outlets that served as samples. Because the charts were reported weekly, it mattered both which stores your records sold at and what day of the week people bought them. Michael didn’t just want sales, he wanted hits, and in the mid-1980s that meant keeping carefully timed plates spinning in tandem. As Gary Farrow, Wham!’s PR manager, told Parsons:

Everybody in the organization adopted a policy that everything was doublechecked. Was the record going out in the best week? Were we giving the exclusive video to the right person? . . . Our set-up was successful because we controlled everything.

Michael discussed his first decade in music like elaborate, competitive queer choreography: “To be fighting every week with Culture Club and Duran Duran and Frankie Goes to Hollywood was exciting,” he told Parsons in 1989. “We knocked off Duran Duran from number one, then Frankie Goes to Hollywood knocked us off, then ‘Careless Whisper’ knocked them off. I really loved all that.”

When Wham! ended, Michael brought the same mentality to his solo career. “He knew exactly from day one what he wanted to do,” Farrow reported. “The photographers he wanted to use, the radio shows he wanted to do, who he wanted to represent him, who he didn’t and why.” In Wham! Michael explains his decision not to come out of the closet in the mid-1980s as a commercial strategy: “I really wanted to come out. And then I lost my nerve completely.” He later adds, “If your goal is to become the biggest-selling artist of, you know, that year or two, you’re not gonna make life difficult for yourself, are you?” He came out officially in the late Nineties, by which time the fact was obvious to anyone who had been paying attention.

As early as Make It Big, there were signs that Michael was pushing at the creative and commercial limitations of what was essentially a boy band: in many territories, “Careless Whisper” was credited to “Wham! featuring George Michael.” Professionally and personally, the shift from a duo of high school friends to a solo career was a big transition, and the music press was rife with stories about Michael setting aside boy-wonderish things to become a brooding man-star; that transition is the narrative climax of Wham! Creatively, however, the two periods had much continuity. Many of the George Michael imago’s “adult” components were in place as early as Wham!’s first single and video: lite funk, heavy syncopation, and Michael in leather stomping the butch queen category down. Beneath the bouncy sheen, later Wham! songs like “The Edge of Heaven,” “A Different Corner,” and the B-side cover “Where Did Your Heart Go?” showed where Michael’s production and songwriting were headed: an earnest influx of soul, a deeper, more spacious approach to mixing, and overt references to sexuality to replace winking, PG-rated allusions.

Advertisement

The real motive behind the change, one suspects, was a felicitous confluence between commercial forces and an artist’s desire to be taken more seriously. By marketing Wham! directly at teens, Michael had limited the kind of records he could make, and the label had restricted their market to a quickly saturated demographic with a finite attention span. For different reasons, perhaps, both Michael and the record company wanted to start selling records to adults.

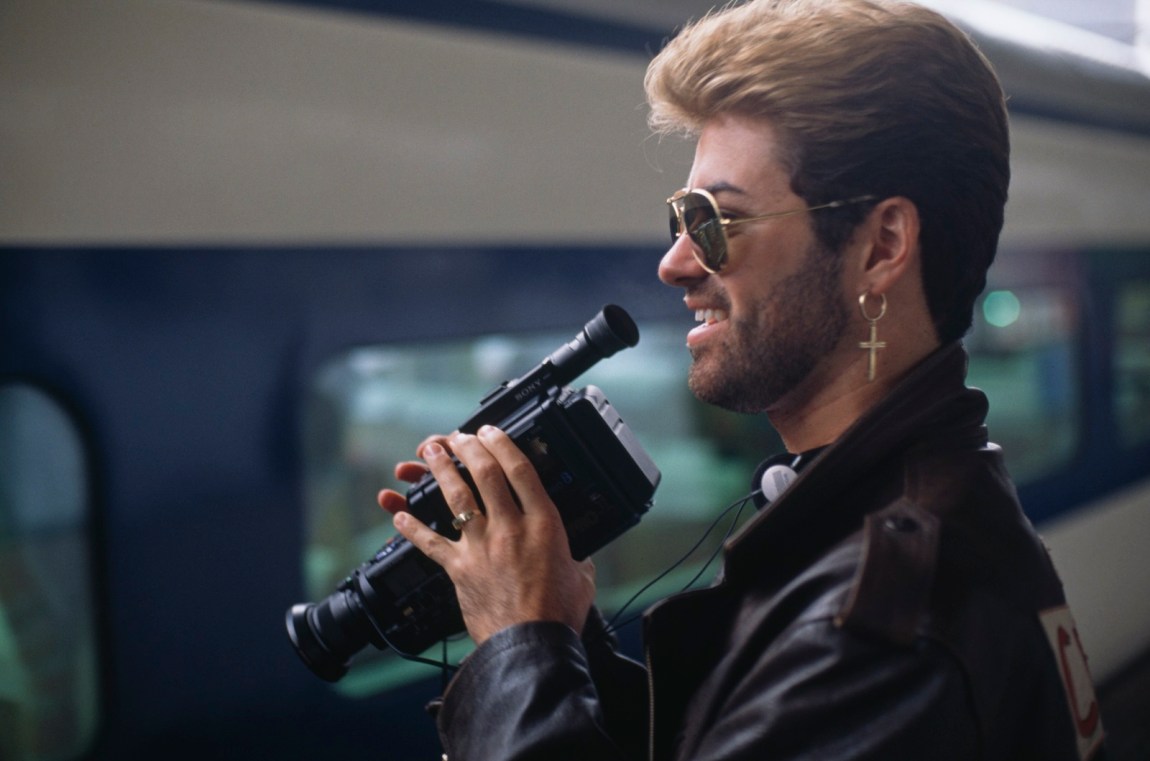

*

Faith, Michael’s first solo record, was the bestselling album of 1988 in the United States, sold millions of copies worldwide, and remains one of the fifty highest-selling albums of all time. Constant video play on MTV was a big part of that success; the other part was a relentless promotional gauntlet, including a world tour spanning 109 dates. Then, after grueling months on the road and years of relentless tabloid fixation as one of Britain’s biggest pop stars, toward the end of 1988 the artist formerly known as Yog decided that he was tired of being George Michael. “A certain phase of my career is ending now,” he told Parsons in 1989. “In the future I don’t intend to show myself the way I have in the past, I will no longer promote and talk to the media the way I did in the past.” He did not plan to stop making music, but he insisted that the marketing for his next record, Listen Without Prejudice, Vol. I, would not include his face. The album cover wouldn’t even feature his name.

“The fact that he didn’t do any promotion of it [is] quite astonishing,” Elton John muses in Freedom Uncut. But the chart mastermind who wrote singles with a release date already in mind can hardly have been naive enough to think he could disengage from the media without commercial consequences—nor indeed did he try to. He announced his refusal to be George Michael in a hardcover autobiography with his name and a glamour portrait on the dust jacket. He refused to do television interviews, but he gave a long and candid interview to the Los Angeles Times about why he wasn’t going to talk to traditional media outlets anymore. He refused to appear in music videos, but he crafted an era-defining, cinema-quality clip for the single “Freedom! ’90,” directed by David Fincher and starring the world’s five most famous supermodels. He made the media so hungry for his face that when he walked onstage at MTV’s tenth anniversary concert to perform “Freedom!” it felt like an angelic visitation. The network gleefully aired that live version over and over, delirious in its acquisition of the singer’s image.

Michael also toured for Listen Without Prejudice, but, true to its name, the Cover to Cover tour largely featured other people’s songs. (Congenitally unable to disappoint fans, he still threaded the set list with his own hits.) Every performance opened with an astounding, improbable concoction: a mashup (more than ten years before the term’s twenty-first century reinvigoration) of The Temptations’ “Papa Was a Rollin’ Stone” with Adamski’s “Killer,” a smash hit in the UK in 1990. Using the acid house synth bassline from the latter, Michael sings over a grinding industrial beat—miles away from his familiar instrumental range—to spectacular effect. A live recording of “Killer/Papa Was a Rolling Stone” was released as a single in 1993, paired with a bleak, surrealistic grayscale video. Neither critics nor audiences were pleased, and the track performed poorly despite extensive rotation on MTV. Michael never took a creative risk like that again.

The rub, it seems, was that Michael wanted to make bold creative and professional choices without losing his status as a global icon and effortless hitmaker. By his own admission, what he wanted from his label was mostly emphatic support:

I explained to them that Faith had taken me to the edge of madness; that I wanted to be a long-term player in this business. . . . Now any logical CEO, I think, would have thought, “OK, he’s gonna do this, he’ll get it out of his system, . . . and he’ll get back on board.”

An urgently organized face-to-face meeting between Michael and US label executives failed to convince them. In 1987 Sony had bought Epic Records, and part of Michael’s frustration stemmed from still being bound to the original, exploitative Innervision contract. After a protracted standoff he declared that he would not release any more music with Sony until they renegotiated his contract or released him from it.

Even as both sides marshaled their legal forces, Michael continued to rack up hits; the album whose “failure” the two were blaming on each other outsold Faith in the UK. The real bone of contention was the US market, much larger but far less amenable to promotional quirkiness, where sales for the second album lagged. Sticking to his word about not giving Sony new music, in 1992 Michael donated three tracks from the planned Vol. 2 to Red Hot + Dance, the second of the Red Hot Organization’s HIV/AIDS fundraising compilation albums. The tracks included “Too Funky,” a sped-up take on Vol. I’s reggae jam “Soul Free.” Like most of Michael’s dancier tracks from the late 1980s and early 1990s, “Too Funky” is palpably influenced by vocal house music but eschews a proper dance beat.

Eventually Michael filed a court motion in England asking a judge to declare his contract with Sony void. After extended litigation, he lost on all counts. Sony hadn’t really won, though; they could stop him from making music for someone else, but they couldn’t force him to make music for them. The result was a stalemate, until David Geffen, hunting big names for DreamWorks SKG’s planned record division, offered to buy out the contract to everyone’s generous advantage. Sony acquiesced.

*

In 1993 Michael’s first committed partner, Anselmo Feleppa, died of HIV/AIDS. The two had met in 1991 when Michael performed in Rio de Janeiro on the Cover to Cover tour. “In the front of these 160,000 people, there was this guy over on the right-hand side of the stage that has fixed me with this look,” he remembered in Freedom Uncut. “I was so distracted by him that I stayed away from that end of the stage for a while.” They fell in love, but within six months of meeting, Feleppa began to show signs of illness. “I will never know if Sony and I would have ended up in court had Anselmo not become ill,” he reflected. “I think to some degree [it] was a perfectly good place to put my anger.”

Feleppa’s death marked the beginning of two years of writer’s block: “I didn’t write a note of music.” The block was finally broken in 1994 when an ad-lib over a simple keyboard loop produced the vocal hook for “Jesus to a Child,” which Michael finished writing in just a few hours and performed on live television in front of an orchestra only days afterward. Two years later it became the first track on Older, his third LP. “There’s not one track on that album,” Michael said, “that is not about Anselmo.”

This time the marketing was textbook. Michael’s face stared out from the record sleeve in chiseled chiaroscuro, he lip-synched in the videos, and he hit every stop on the standard promotional junket. In the US Older barely sold, and his star seemed definitively to fade, but in the UK the album permanently cemented his celebrity: it still holds the record for most Top 3 singles pulled from one album. The pious passion of “Jesus to a Child” was followed by the midtempo electro-sleaze of “Fastlove,” an ode to casual sex and an informal coming-out. In the video Michael gyrates, dripping wet in an open shirt, as if to show Sony what they could have had if they’d just let him get the faceless thing out of his system.

“Older is my greatest moment,” Michael says in Freedom; nearly thirty years after its release and eight years after his untimely death, that seems a fair assessment. Not exactly a major departure, it was a fresh and more expansive take on a now familiar sound. Michael’s coproducer, Jon Douglas, helped replace the usual syncopated drum machines with a live band on many tracks, giving them a looser and more improvisational feel. The album also pushes deeper into dance music than Michael’s previous work, most notably on “The Strangest Thing.” For the single remix, the album’s hushed, sparkling campfire groove is transformed into a full-on club stomp without losing its hypnotic pull.

George Michael’s ability as a pop producer and songwriter—his proven skill at making songs “jump out of the radio”—rested within a fertile but fairly predictable set of parameters: deep soul, light funk, heavy syncopation, a sprinkle of two-tone reggae. A lot of rhythm; just enough blues. Even genres directly adjacent to his comfort zone, like house and disco, didn’t make an appearance in his catalog until he brought in a coproducer. His career was driven by two imperatives. The first was to achieve and maintain a demonstrable level of popular success, not only quantifiable but accredited, measured in hits. The second was to be taken seriously as an artist, not just as a teenybopper idol or a commercial hitmaker. The two imperatives were not necessarily contradictory, but when they came into conflict the commercial imperative almost always won out. “Once I had a taste of it,” he said, “it was very addictive.”

When the two imperatives operated in tandem the outcome was not only successful but genre-defining.* His perfectionist insistence on doing what he knew best again and again but better and better helped cement “pop” as a general designation not just for currently popular music but also for a recognizable (but hard to define) blend of elements borrowed mostly from historically Black genres. It’s easy to break “Freedom!” into its component parts—a dressed-up funky drum sample, bossa nova piano, a Motown melody with gospel harmonies—but there’s no word for the resulting cocktail except “pop.” What makes the song distinctive even today is its double-time bossa nova spine: by 1990 funk, Motown, and gospel had all become familiar parts of the pop palette.

Isolated corners of Michael’s discography offer glimpses of the directions he might have taken. Years before the first four-to-the-floor beats showed up on Michael’s own tracks, Shep Pettibone, who cochaired Madonna’s house-soaked 1993 album Erotica, made a remix of “Hard Day,” the third single from Faith. What if Michael had really made an album for the dance floor and not the pop charts? The B-side to “Freedom! ’90,” a studio hybrid called “Freedom! (Back to Reality mix),” interpolates pieces of Soul II Soul’s “Back to Life” and samples both the record scratches from Neneh Cherry’s “Buffalo Stance” and the violin solo from Sinéad O’Connor’s “I Am Stretched on Your Grave”; it suggests that “Killer/Papa Was a Rollin’ Stone” came from an adroit facility for genre-blending and beat-matching. Clearly, Michael avidly followed new developments in music production and sound even as his albums continued to trace more familiar parameters. There are also live recordings that hint at a looser, more adventurous vocal style than the ornamented restraint of his studio work.

Unlike many artists who tread close to the middle of the road, Michael made a conscious choice to limit his sonic palette. His late-era solo work may not have sounded much like early Wham!, but there are only a few songs in George Michael’s catalog that don’t sound like George Michael.