A wannabe criminal who could when he chose draw like an angel, Stéphane Mandelbaum (1961–1986) was the child of two artists, bequeathed at birth the heritage of two genocides. Relatives of his Polish Jewish grandfather were murdered during World War II; relatives of his mother, of Armenian descent, were massacred during the ethnic cleansing of Anatolia. A French-speaking Belgian, Mandelbaum connected with another world-historic atrocity when he married a woman whose parents grew up in the then-Belgian Congo.

Although raised without religion, Mandelbaum decided in his teens to identify as a Jew, at least culturally, learning Yiddish, one suspects both to claim pariah status and perhaps to live out the phrase “shver tsu zayn a yid” (hard to be a Jew). The only painting included in his first American show—an exhibition at the Drawing Center in New York City, organized by Laura Hoptman in collaboration with Susanne Pfeffer—is a full-length self-portrait of the artist, tastefully disemboweled and floating before a row of meat hooks.

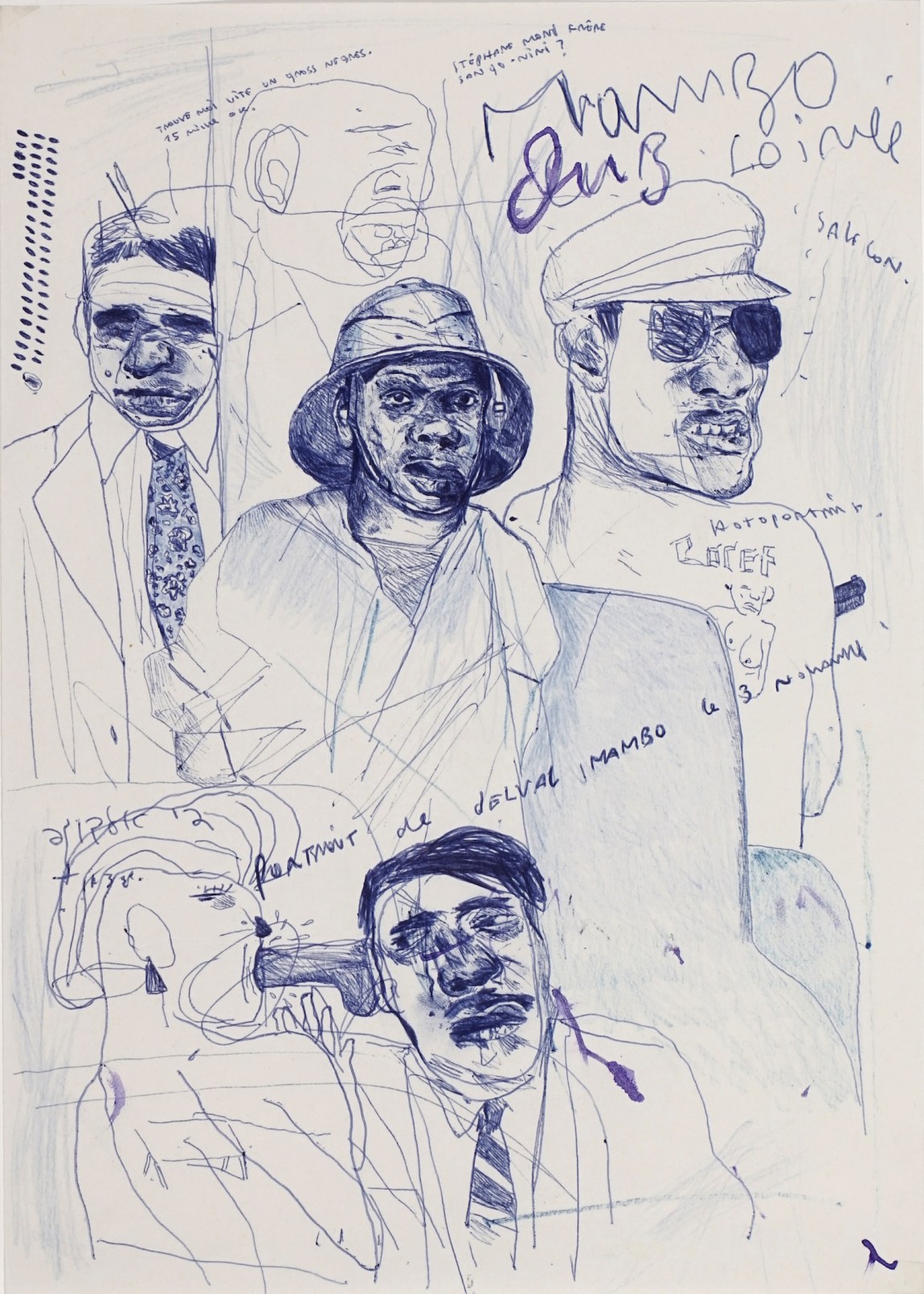

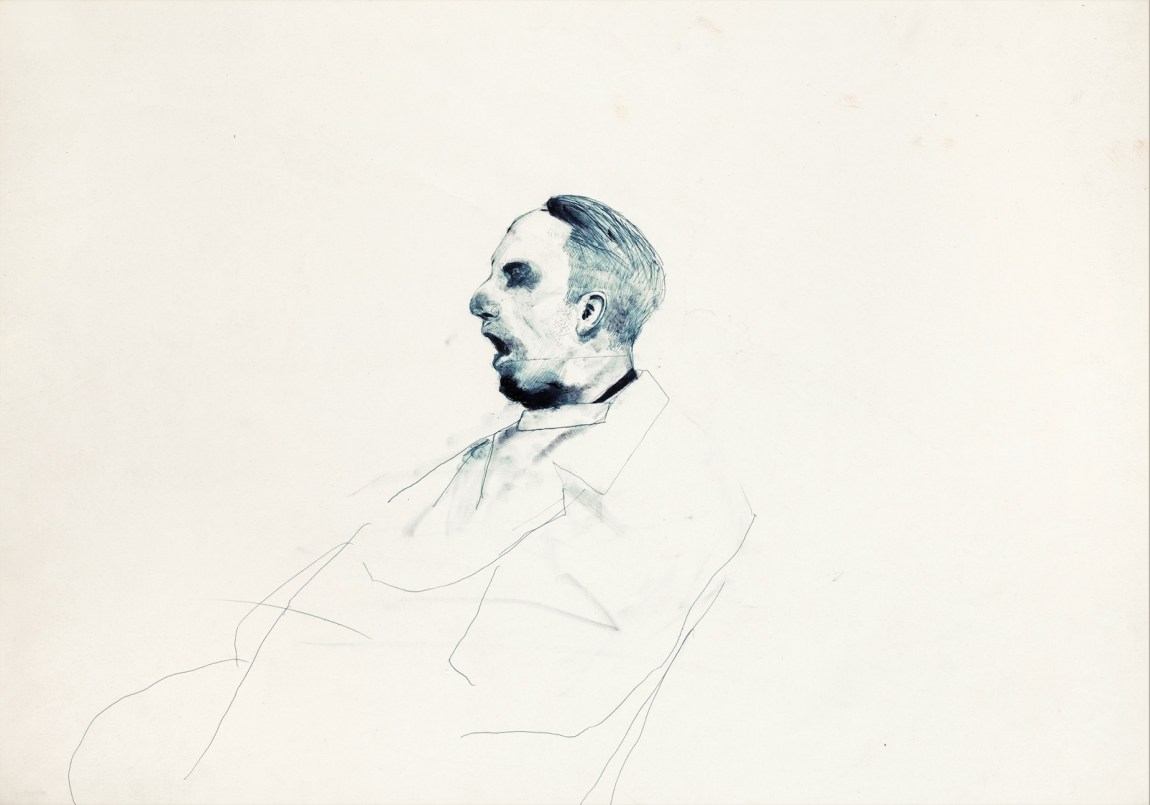

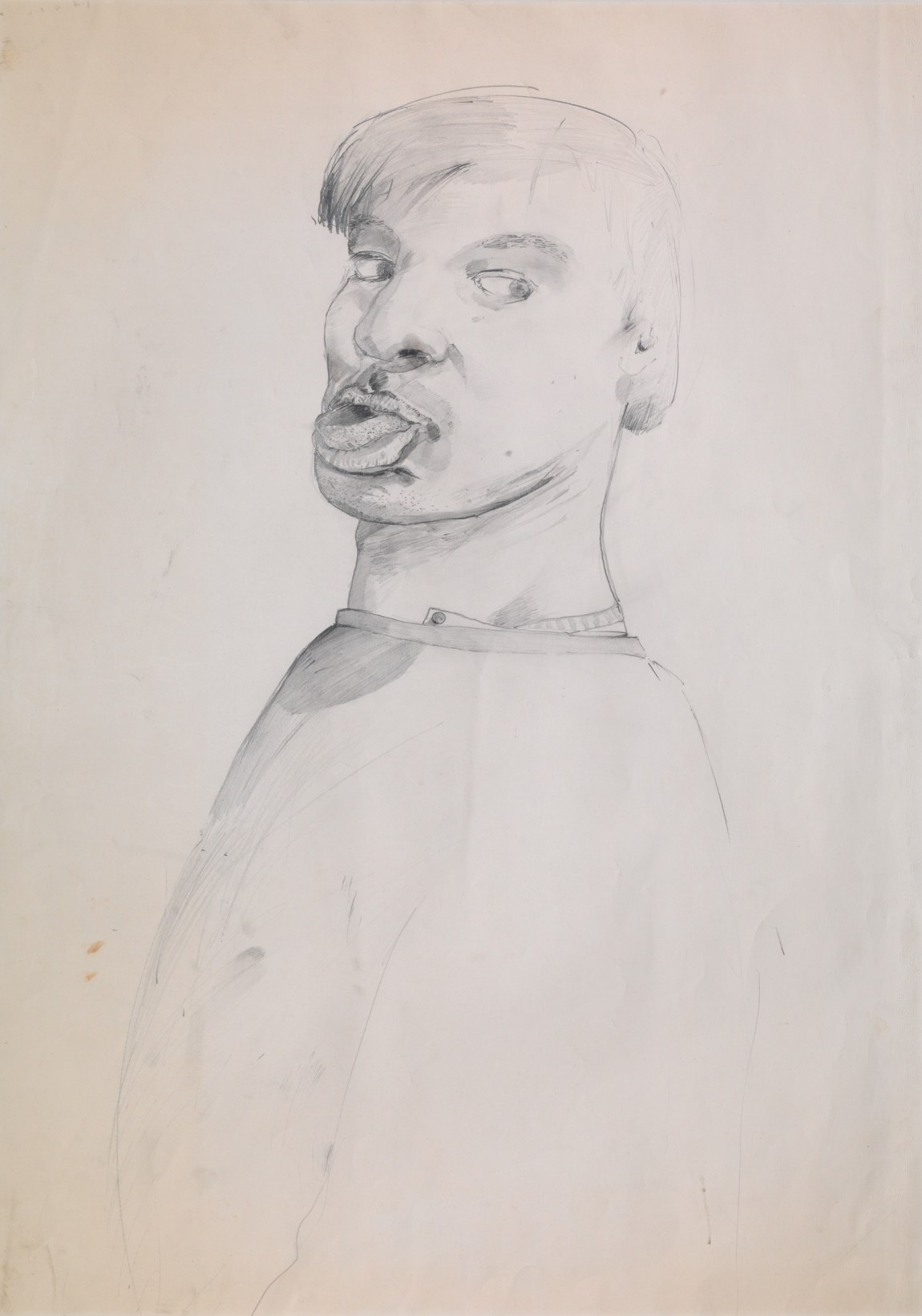

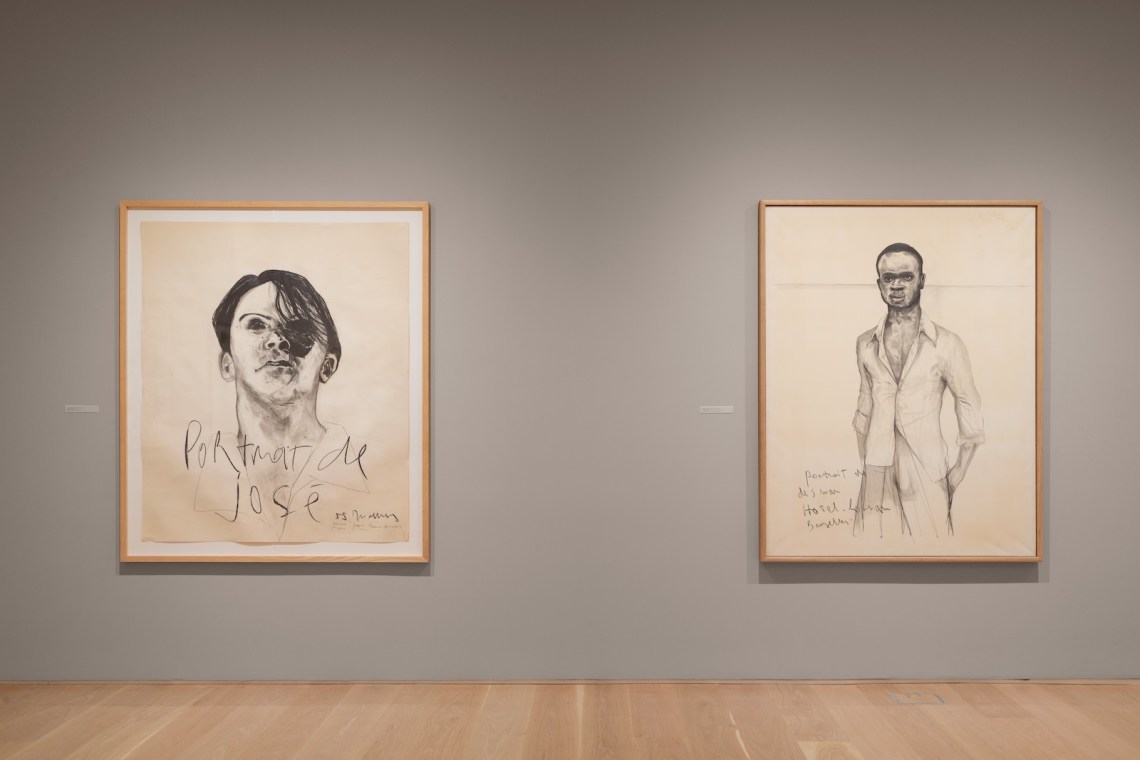

Dated 1976, the painting is uncharacteristically finished. Many of Mandelbaum’s subsequent graphic portraits feel abandoned. They are fastidious yet compulsive, filled with tenderness and disgust. His pencil-drawn character sketches—mainly based on photographs and often surprising large, some five by four feet—have, in their facility and fetishism, a quality reminiscent of R. Crumb’s fanboy likenesses. But where Crumb amused himself with loving portraits of old blues singers, Mandelbaum drew the louche habitués of Brussels dives and brothels (an inside joke places the venerable Yiddish entertainers Henri Gerro and Rosita Londner at the Mambo Club) along with portraits of his father and grandfather, defaced while stolidly dignified. A bad-boy punk, Mandelbaum repeatedly portrayed renegade artists—Arthur Rimbaud, Pier Paolo Pasolini, Rainer Werner Fassbinder—and, most provocatively, Nazi leaders like Joseph Goebbels and Ernst Röhm.

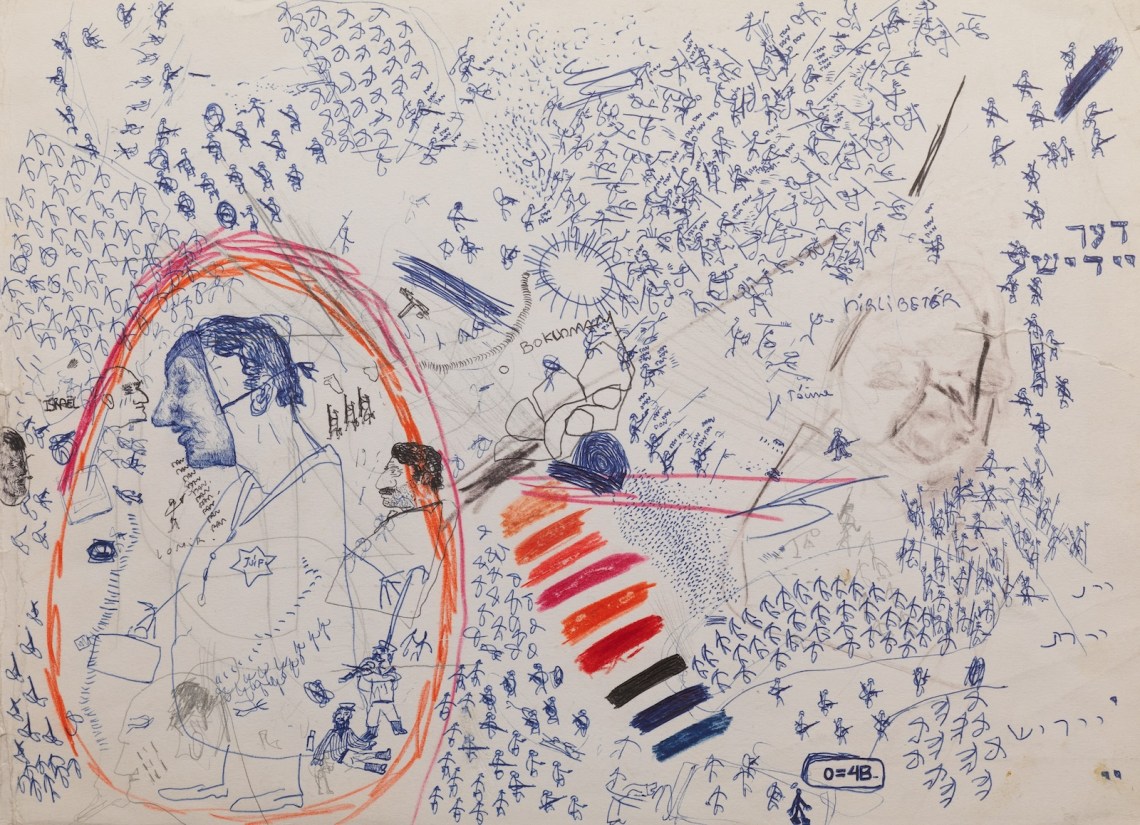

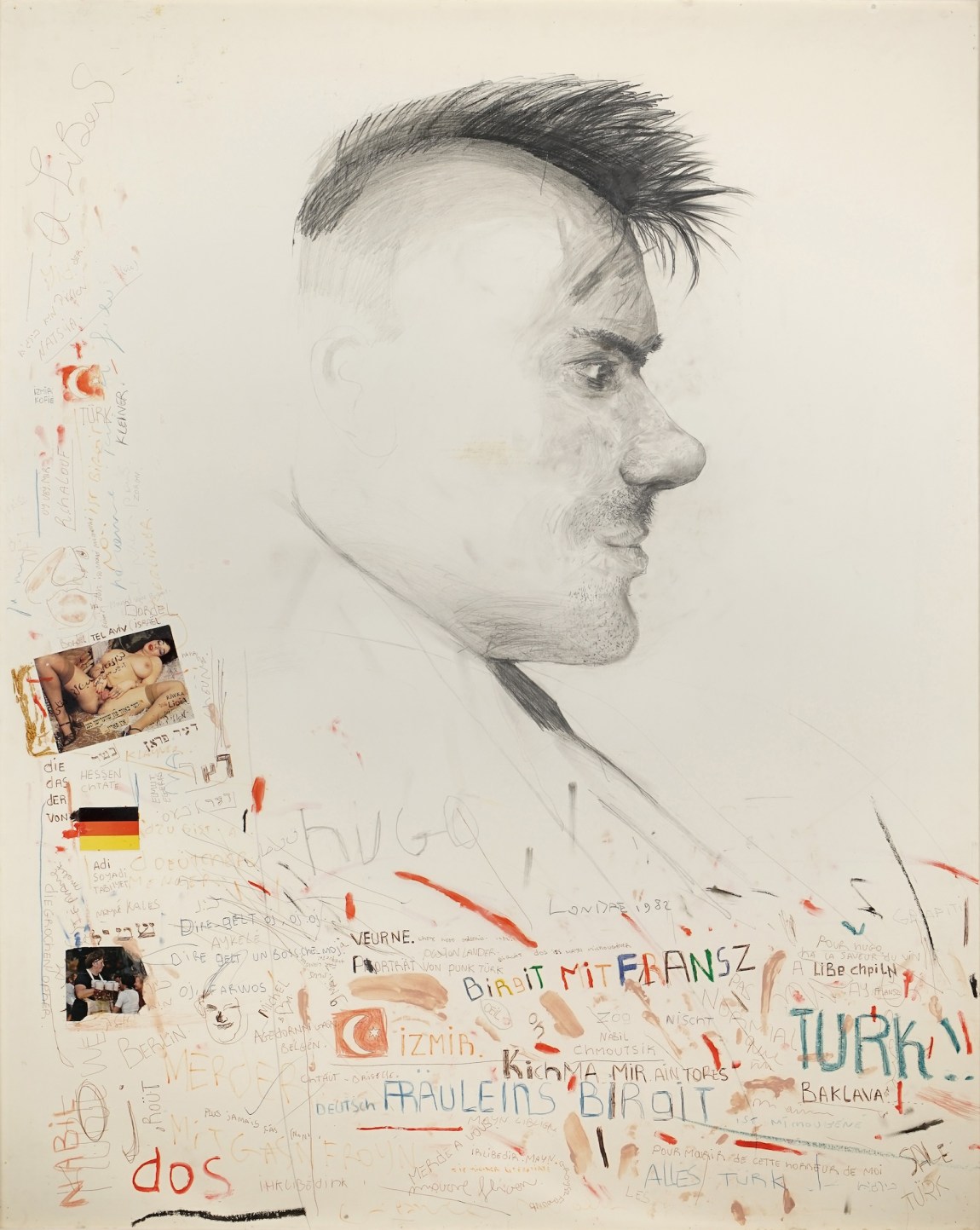

These are hermetic, confrontational works, which typically mix accomplished if half-finished figurative images with bits of collage, obscene doodles, and scribbled text. They have obvious points of contact with the work of Mandelbaum’s near-contemporary Jean-Michel Basquiat. Like Basquiat, Mandelbaum was an outsider, grandiose yet self-effacing. His delicately rendered portraits are crudely annotated, mainly in French and Yiddish. The ambivalent artist despoils his work even as he heralds it. An admiring, near-formal portrait of his father Arié Mandelbaum has the bold Yiddish inscription “kish mir in tuchus!” (kiss my ass!). At the portrait’s left corner is a small collage in which a photograph of a woman’s naked torso clipped from a smutty magazine has the face of a grinning Nazi officer.

Mandelbaum’s juxtaposition of atrocity and porn was anticipated decades before he was born by two Holocaust survivors: the American artist Boris Lurie, whose still-shocking canvases placed mounds of corpses alongside bodacious pinups, and the Israeli writer who, taking as his pen name his concentration camp number, Ka-Tzetnik 135633, wrote House of Dolls, a lurid account of sexual slavery at Auschwitz. (For many years the book was required reading for twelve-year-old Israelis, providing their introduction to the Holocaust with a ghastly element of titillation.)

Two generations removed from Lurie and Ka-Tsetnik, Mandelbaum scandalizes with his diffidence. His Goebbels is mindlessly dynamic, speaking into the void, mouth open, with the dead eyes of a shark. His Röhm seems mildly depraved, given the Hebrew seal of approval כָּשֵׁר (kosher) in one 1981 portrait, which also includes an erect penis. Another portrait of Röhm from the same year has concealed, in a field of multicolored weeds, the scrawl “sale juif” (dirty Jew). It’s unclear whether the artist is contemptuously outing his subject or proudly signing his name.

*

Mandelbaum, who struggled with dyslexia, drew constantly as a child, so proficiently that he had his first exhibition at age nine. He attended two Brussels art schools, including one at which Arié was director, and even helped his father as a teaching assistant. In his late teens he grew close to his paternal grandfather, who had managed to survive the Holocaust in Belgium. Stéphane soon learned Yiddish and exhibited in a show called “Nine Jewish Painters.” He was surely aware of the filmmaker Samy Szlingerbaum—whose poignant film Brussels Transit (1981) used Yiddish to memorialize his parents’ dislocation—and, according to Leslie Camhi’s knowledgeable catalog essay, he saw Claude Lanzmann’s nine-hour Shoah (1985) several times in the last year of his life.

Most significant, perhaps, was the example of Felix Nussbaum, whose lost paintings were discovered during Mandelbaum’s adolescence. The subtly surreal work of this German Jewish artist, who took refuge in and was deported from Brussels, is not easily forgotten. Death Triumphant (1944) is a sort of cultural Last Judgment in which a band of grinning, shrouded skeletons play music amid the wreckage of European civilization, and Self-Portrait with a Jewish Identity Card (1943) renders the artist’s mental state with a hallucinated clarity. But created as it was after Auschwitz, Mandelbaum’s oeuvre is purposefully more barbaric.

Advertisement

Mandelbaum’s smaller work, usually executed in blue or black ballpoint pen, is in every way his sketchiest, replete with random cocks, images of cock-sucking, and stray swastikas. (The latter reminded me of the graffiti I was bewildered to see carved into the desks at the Hebrew school in Queens I briefly attended.) כָּשֵׁר is common. So are antisemitic stereotypes. In one impossibly busy drawing, a pious Jew seems to daven to a pig’s head. An even greater desecration—the words to “Zog nit keyn mol,” the anthem of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising—appears beside a Jewish caricature suitable for Der Stürmer. Another piece is simply a long list of concentration camps embellished with a tiny palm tree and the come-hither inscription “a sheyne-bilder panorama,” which suggests a slideshow of a pleasing landscape.

Such work might have found a home in the Brooklyn Museum’s current epic survey of zine-making, “Copy Machine Manifestos,” although compared to most of the artists shown there, Mandelbaum is a Caravaggio. He essentially created his own subculture. He may or may not have been queer, but many of his subjects were (not least Röhm). Not that they received the Tom of Finland treatment. Lean and handsome in life, Pasolini is drawn as a puffy-faced paranoid and a cheesy martyr. In one picture he appears next to a pasted devotional card: Blood oozes from Jesus’s chest as a winged cherub hovers above. Over Christ’s loincloth the artist has pasted a penis.

*

Rimbaud and Francis Bacon were Mandelbaum’s artistic idols, and he sketched them often. But it was another frequent subject, the tormented French radical Pierre Goldman, who seems to have been his ego ideal. A would-be revolutionary who described himself as an “exiled Jew without a promised land,” Goldman was born during World War II to a Jewish Communist couple active in the French Resistance. Desperate to live up to their heroism and nursing “a fierce and Jewish hatred” of the police, Goldman identified with French colonial subjects, consorted with thieves, sex workers, and Latin American guerrillas, and ultimately turned to crime.

In addition to being arrested for a string of holdups, Goldman was charged with two murders committed during a drugstore robbery; he admitted to the other robberies but adamantly maintained he had been framed for the killings. Mandelbaum’s father gave his son Goldman’s novelistic autobiography Dim Memories of a Polish Jew Born in France, written in prison and first published in 1975. The book impressed Mandelbaum fils with its demimonde adventures. Then came Goldman’s stormy second trial and, following his acquittal, his apparent execution, shot down gangland style on a Paris street in 1979.1

One of the Drawing Center pieces featured Goldman presiding over an image of the actress Eiko Matsuda in ecstasy, copied from Nagisa Oshima’s homage to mad love, In the Realm of the Senses (1976), and a parody of Guernica (with the inevitable uncircumcised penis). Mandelbaum’s portrait of a smiling shohet (ritual butcher), long knife in hand, includes both the title of Goldman’s Dim Memories and a quotation from the book in which, recounting an evening passed among the Cabo Verdean patrons of an Antwerp saloon, he recalls or imagines dancing with “a young Jewish prostitute” who miraculously addressed him in Yiddish and Polish: “She looked at me with a kind, wan smile that seemed to come from a childhood spent in mourning.”

One can well imagine Mandelbaum being moved by that angelic visitation and impressed with Goldman’s solution to the impasse at which he found himself. Stuck in Paris, unable to foment revolution in Venezuela and disgusted by the events of May 1968, which he regarded as bourgeois student posturing, Goldman turned to crime, almost as a surrealist performance. (In his memoir he describes an abandoned attempt to mug Jacques Lacan.) Like Goldman, Mandelbaum sought out criminal associates, and like Goldman he met a violent end.

Advertisement

Unable to exhibit, let alone sell, his work, Mandelbaum began trafficking in stolen art. In the spring of 1986 he traveled with his wife, Claudia Bisiono-Nagliema, to her home village in Zaire, having hatched a Rimbaudian plan to smuggle African artifacts back to Belgium. Whether or not he succeeded, he did pull several heists on his return. The pilfering of some Netsuke statuettes was followed by a more ambitious attempt to steal an elderly woman’s Modigliani. The burglary went south—apparently the painting was forgery—and Mandelbaum wound up dead in a ditch, murdered and mutilated by his associates.

Mandelbaum’s art may not have attracted much attention during his lifetime, but his violent end made local headlines. In the thirteen years that followed, he was the subject of three movies. In 2014 the French Jewish writer Gilles Sebhan wrote a nonfiction novel called Mandelbaum ou le rêve d’Auschwitz; in 2019 Mandelbaum was exhibited in an out-of-the-way gallery at the Centre Pompidou. Although the show did not contain his most outrageous work, gallerygoers were cautioned to brace themselves for vulgarity and violence. The hometown audience was better prepared. Thirty-two years after Mandelbaum was refused burial in Brussels’s Jewish cemetery, officially because his mother wasn’t Jewish, his chosen identity was belatedly acknowledged with a retrospective at the Musée Juif de Belgique.