I. Andrew Katzenstein in Mason, Texas

II. Willa Glickman in Rochester, New York

III. Daniel Drake in Warren, Vermont

IV. Lucy Jakub in the Rangeley Lakes, Maine

🌘 🌗 🌓 🌒

Riders in the Sky

Andrew Katzenstein in Mason, Texas

I learned about this year’s eclipse in late 2016, when I read an article in The New York Review by James Gleick, who mentioned it in a discussion of scientific determinism:

There is a strain of physicist that likes to think of the world as settled, inevitable, its path fully determined by the grinding of the gears of natural law…. If scientists say the moon will totally eclipse the sun in New York on April 8, 2024, beginning at 12:38 PM, you can bank on it. If they can’t tell you whether the sun will be obscured by a rainstorm, a strict Newtonian would say that’s only because they don’t yet have enough data or enough computing power. And if they can’t tell you whether you’ll be alive to see the eclipse, well, maybe they haven’t discovered all the laws yet.

Unfortunately, Gleick’s hypothetical scientists were off by nearly three hours; totality didn’t begin in New York State until around 3:17 PM EDT.

Gleick was reviewing the time-travel film Arrival. His point was that some physicists view the past and future as “merely different places, like left and right,” and thus overlook the effects of chance and will on the course of events. He could have picked from any number of phenomena to set up the contrast between physics and history. But the random example struck me because April 8, 2024, would be my thirty-third birthday. The coincidence seemed slightly spooky to my twenty-five-year-old self, in light of all the tragic Faulkner characters who are thirty-three, the age at which Christ was crucified. I think I’d also recently read Ottessa Moshfegh’s Homesick for Another World, in which one of her most grotesque and self-pitying narrators refers to being in his “Jesus year.”

I didn’t have especially grandiose expectations about turning thirty-three, but provided that I would still be alive in 2024, a total eclipse seemed like a nice way to spend a birthday. My girlfriend, Celeste, whom I met a week after I turned twenty-eight, also liked the idea, and for years we planned to travel into the path of totality. Last summer we settled on central Texas, since it had a high chance of clear skies and would be easier to get to than Mazatlán, Mexico, which was even likelier to be sunny. Over the past six months or so, our itinerary came together: we’d spend some time in New Orleans, where our friends Maya and Alex live, and drive with them to Canyon Lake.

As it happened, and as no meteorologist could have accurately predicted in 2016, a rainstorm nearly ruined our trip. We arrived in New Orleans on the night of Monday, April 1. By then weather forecasts for the eighth already looked worrying. Cloud cover at Canyon Lake—on the eastern edge of the path of totality and about an hour away from both Austin and San Antonio—was predicted to be at around 85 percent; similar predictions were made for the rest of the strip of central Texas that lay in the path of totality. But we had our apartment reservation, so we stuck to our plan.

We spent the night of Saturday, April 6, in Houston, in a dreary apartment complex in the Montrose neighborhood. The unit we stayed in had prints of zoo animals dressed in suits and ties and eyeglasses. When we left on the morning of the seventh, we realized that all the apartments in the complex were nightly rentals, and every window we walked by revealed the same tacky art on the walls.

From Houston it was another three and a half hours to Canyon Lake. On the way we listened to a reading of Annie Dillard’s essay about the total solar eclipse that she saw in Washington State on February 26, 1979. Dillard regretted that one of her most vivid memories of the experience was a painting of a clown in the hotel she stayed at, and Alex joked that the prints of bespectacled animals would later be the clearest detail from our trip. Electric signs on the roadside announced a prohibition that people were sure to disregard:

NO STOPPING

ON HIGHWAY

TO VIEW ECLIPSE

In an effort to reduce backups, other signs offered travel advice that also sounded like a prayer for a longer totality:

ECLIPSE

ARRIVE EARLY

ECLIPSE

STAY LATE

The eclipse was due to start around 12:30 PM CDT, totality a little more than an hour later. On the morning of Monday, April 8, the Austin radio station KXAN reported that the skies would be overcast from Canyon Lake to Fredericksburg, about an hour northwest of us and the tourism center of the Texas Hill Country. Clearer skies were predicted even further northwest in Mason. We decided to try Fredericksburg first and continue to Mason if necessary. We left around 10:00, passing a nearby church called Cowboys for Jesus. The night before we had found a brochure for it in the apartment. On one page it answered a frequently asked question: “Do you have to be a Cowboy? Absolutely not, but if you like a little country music and are down to earth country folks, chances are good you will like our country atmosphere.”

Advertisement

The traffic moved steadily. Vultures circled in the sky, and wildflowers carpeted the roadside. We were in LBJ country, and I wondered if Lady Bird’s passion for highway beautification began while driving along those lush pasturelands. A few streaks of blue sky appeared as we crossed the Gillespie County line around 10:30. We passed crowded RV parks and a hotel fortuitously called the Full Moon Inn.

KXAN had reported that the 100,000 visitors expected in Fredericksburg, right in the center of the path of totality, “must have changed plans” owing to the forecast: storeowners complained that foot traffic over the weekend had been normal for the season. But when we drove through downtown on Monday morning, it was full of people buying food and drinks and gathering in the Marktplatz, the main square of the town, which holds fast to the German roots of its early inhabitants.

Following the advice of an electric sign by the roadside, we tuned in KNAF 910 AM, Texas Rebel Radio, for weather updates. A host named Big Daddy Waldo was interviewing a man who had traveled to Fredericksburg from California. Another announcer, Texas Trish, reported that Mason was still expected to have about 50 percent cloud cover, so we decided to head there—the sky above Fredericksburg was gloomy. As we left town, it brightened slightly.

*

Cars were parked along the side of Route 87, with people setting up telescopes and tents. Around 11:45, KNAF reported that there was sun at Fort Mason, and available parking spots too, so we set our course for it. The station played a country song with the refrain “Hooves on the fly/Dead on the run/Throw my lasso round the West Wind/And ride on chasin’ the sun.” (The bridge featured yodeling, and on the tinny AM wavelength it sounded like it could have been recorded in the 1950s, but I later found out it was recorded in the 1980s by the cowboy novelty group Riders in the Sky.) The blankets of cloud were finally breaking up. KNAF warned listeners who were in their cars during the eclipse not to drive with the special sunglasses on.

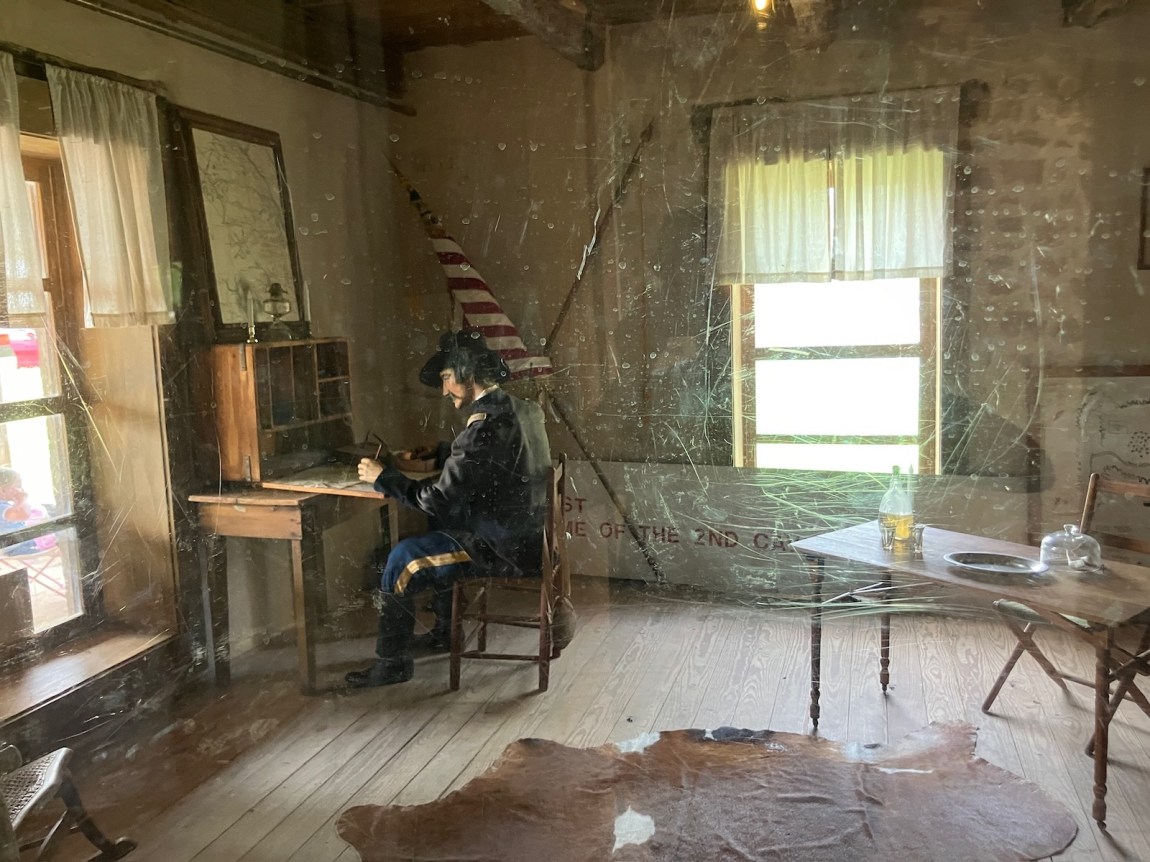

We arrived at Fort Mason around 12:30, about a minute after the partial eclipse began. There were twenty or so cars parked on the road that passes by the fort, which sits on a small hill and has a clear view of the plains to the north; the view southwest, where we would be facing to watch the sun, is occluded by houses and trees. I learned from a sign outside the fort that it was established by the US Army in 1851 and was the last command post held by Robert E. Lee before he defected to the Confederacy. (A placard inside the fort noted that, at an earlier posting in Texas, Lee had kept a pet rattlesnake. He wrote to his daughter in 1856, “My rattlesnake, my only pet, is dead. He grew sick and would not eat his frogs, etc.”)

A few men in late middle age had set up telescopes. Some families with young children were sitting on blankets and chairs in the small field next to the fort. A teenage boy was reciting eclipse facts for his friends, who didn’t seem too impressed. A man wore a shirt from the 2017 eclipse, and another had on a shirt that said, “I MAKE CUTE BABIES.” (His daughter, though about four or five, was indeed pretty cute.)

The sky around the sun was mostly clear. At 1:10 we wondered if it was getting darker around us. We were about twenty minutes from totality. No more people were arriving; presumably everyone in Hill Country had settled down somewhere. We took turns laying under a small oak tree to let the crescent-shaped beams of light fall on us. A boy of about eight put a pair of eclipse sunglasses on his Pikachu doll.

We noticed the temperature dropping at 1:20. High winds kept the clouds moving. It felt a bit foreboding, like the onset of a tornado. Five minutes later the sun was just a glowing filament; the plains behind us were in half-light, and everything took on the silver-gelatin or daguerreotype sheen that Dillard describes. I heard a boy use a more modern photographic analogy: “It looks like I’m viewing everything through a filter.”

Advertisement

There was a hush when totality hit, at around 1:35. The sky was still clear around the solar corona, and the clouds on the horizon gave off a lovely opalescent glow. Another boy said, “The crickets, they think it’s night.” A single firework went off. The streetlights turned on in the plains to the north. A few birds chirped, and then, around 1:38, it was over. Someone in a house below us blasted “Here Comes the Sun.” People cheered. Celeste jokingly tried to get us to join her in chanting “ECLIPSE ARRIVE EARLY, ECLIPSE STAY LATE.” Maya said, “I want to ride it again! I want to go back on!”

It took nearly five minutes for anyone to start moving. We all lingered in the silver light. A teen tried to move his family along, telling them, “Okey dokey, artichokey.” Around 1:45, gold seeped back into the light. One of the older men with a telescope told another, “It was worth every minute. I’d do it all over again.” Two other old men, both burly and bearded, were wearing purple wildflowers, one in his baseball cap and the other in his shirt pocket.

In her eclipse essay, Dillard strains, sometimes desperately, to describe the experience of totality: “The eyes dried, the arteries drained, the lungs hushed. There was no world. We were the world’s dead people rotating and orbiting around and around…. Our minds were light-years distant, forgetful of almost everything.” It’s understandable that she would resort to emphatic metaphor and anaphora to convey what she saw and felt. I’ll remember the silvery light and the view of the streetlights turning on in the odd twilight over the plains, but almost immediately after the sun poked out from behind the moon, I realized that the experience was already lost to me. The memory of totality was a beautiful blankness, like a thick monochrome painting, but as a result everything around it stood out more brightly, much as the moon’s silhouette makes the solar corona vividly visible.

We started driving back to Canyon Lake around 1:55. By 2:00 the sky was almost completely overcast again, and five minutes later it began to rain. Since the sun was now obscured, I could only catch glimpses of the remaining partial eclipse. Maya said the sky had stayed clear during totality because she had prayed to the Cowboy Jesus. But meteorology and chance surely helped us too. 🌘

Inner Totality

Willa Glickman in Rochester, New York

From the rooftop of the Genesee Brew House the Rochester skyline rises behind High Falls, where the brown Genesee River pours off a cliff in the center of downtown. It once powered the mills that earned Rochester the nickname “Flour City” in the nineteenth century, when it shipped hundreds of thousands of barrels per year to New York City on the Erie Canal. The office towers of Kodak and Xerox went up during other periods of economic boom, though Kodak is much diminished today, having filed for bankruptcy a decade ago, and Xerox Tower was renamed Innovation Square by its new owners after the company packed up its headquarters and left the city. Topped with an Art Deco aluminum sculpture of sweeping “Wings of Progress,” the former Genesee Valley Trust bank provides the view’s most striking silhouette. The building’s cornerstone was laid on October 29, 1929—“Black Tuesday,” the most dramatic day of the stock market crash that inaugurated the Great Depression.

I had come with friends to watch the eclipse, an exercise in collective expectation. We kept a close eye on Facebook missives from the meteorologist Eric Snitil, who warned that cloud cover was increasingly likely—Rochester is one of the cloudiest cities in the US—but reassured us that this would still be one of the most meaningful experiences of our lives, something we would tell our children and that they in turn would pass down to the next generation. I was feeling apprehensive, having been primed by Annie Dillard’s hair-raising essay, but at the same time hoping for something profound enough to justify the eight to ten hours of gridlock traffic, grimly foretold by Reddit threads and parents everywhere, that apparently would be added to our return drive.

We were hosted by my roommate’s family, and my roommate, a devoted Rochester native, gave us an insider’s tour of the city, which feels lively despite its history as a manufacturing town buffeted by decades of deindustrialization. Many of my roommate’s childhood friends still live in the area, working in education and healthcare, stopping by one another’s porches and backyard campfires on the weekends. We visited bookstores and museums, a dive bar where patrons danced salsa on a Twister-dot floor, and a coffeeshop with a bulletin board that advertised noise bands and art shows and a queer prom. Early spring had dotted the brown landscape with forsythia blossoms and little blue Glory-of-the-Snow.

Outside the coffeeshop, when a man struck up a conversation, I asked if he was nervous about the eclipse. “I might not watch it in a heavily populated area,” he said.

I was tipped off about a workshop on the shores of Lake Ontario at which people were learning how to embrace their “inner totality.” Though it was wrapping up by the time I arrived, I was able to speak with a participant, who was gently waving a burning stick. Sarah Coppola, a massage therapist and cranial sacral practitioner, said that the ceremony, which involved breathwork and intention-setting, was focused on community and connecting with nature. She also briefly mentioned the need for protection.

I was eager to hear more about the eclipse’s potential adverse effects. Coppola, who was studying Vedic astrology, said that “in that tradition, a lot of times people will just not go out under an eclipse at all.” She explained that eclipses involve the astrological bodies Rahu and Ketu, who symbolize shock and delusion, respectively. “Those aren’t things that we want to really invite into our lives,” she said. “In general, it’s not considered an auspicious thing when the source of our life is blocked.” She planned to resist these influences by fasting and reciting mantras, but suggested that other, less spiritual observers could surround themselves with loved ones, and “at the very least not get bogged down by pettiness or any type of inconsequential things.”

*

Later in the day I visited the Erie Canal, which I was eager to see after having sung the lyrics “Giddyap there mule, here comes a lock” in my New York City public elementary school without much of a sense of what they referred to. I was surprised to see that it was barely inches deep in places—parts of the canal are “dewatered” for the winter—and hardly industrial, next to a busy walking path and clutch of stores.

Along the canal’s banks, we stopped at A Frog House, a project of Margot Fass, a psychiatrist who has opened a frog advocacy and education center in a small cabin in her daughter’s backyard. She told the story of how she had become a self-proclaimed frog lady: she had noticed frogs recurring in paintings she was making, and after reading Elizabeth Kolbert’s The Sixth Extinction—which describes amphibians as the most endangered class on earth—decided, “this is my life now.”

“Why people want to put pesticides on their lawn, I don’t understand,” she said. “Actually I do understand. Not all people want to know things.” She was coordinating with local government to try to convert some of the land near the canal into a protected wetland. Inside the tiny house were a number of dreamlike frog paintings. She spoke of how the eclipse revealed the interconnectedness of people, animals and nature: “We’re all energy.”

Just before the eclipse, after a lunch of leftover garbage plates—a famed Rochester amalgam meal of hamburger patties or hot dogs, fries, macaroni salad, bread, raw onions, and meat sauce—we attended an eclipse celebration hosted in the parking lot of the elementary school my roommate had attended, which was painted with large murals of Frederick Douglass, who lived in the city from the late 1840s to the early 1870s. Kids were shooting off small bottle rockets, making cyanotypes, and ignoring telescopes due to the clouds. The coach of the robotics team, a young woman wearing a globe-patterned paper lantern as a hat, told us about her students’ creations.

We were late getting to the park where we had planned on watching. We walked quickly past families sitting on porches in matching black shirts emblazoned with a golden sun, past men standing by the road drinking beers, past an older woman sitting on a tree stump alone on a hillside, past people in lawn chairs in front of a Frederick Douglass monument, past teens sitting on a cannon. We started to run uphill through the park, past denser and denser clutches of people arrayed in all different directions, sprawled on blankets among blossoms. We reached the reservoir at the top and plopped down amid clouds of weed smoke just before the light started to dim. I felt a small thrill of dread as the crowd fell silent and the sky, thick with striated clouds, took on a sepia tone, nightmarish against the red of an American flag on a pole. A strip of horizon under the low-lying disc of the sky turned sunset-yellow in one direction and deep blue in the other—then the blue rushed over us. I could feel the roundness of the moon’s shadow hovering above. People cheered and took photos; a man next to us said, “I wish it was like this all the time.”

Soon the blue edge turned yellow, and the yellow blue, and the light returned. I felt refreshed, as if having slept through a very brief night, and pleasantly short on words—or, perhaps, delusions. I was happy to see the spring flowers and the faces of friends and strangers emerge safely. There was no traffic on the way back. 🌗

Look the Omen in the Face

Daniel Drake in Warren, Vermont

In Vladimir Nabokov’s story “Signs and Symbols,” an old Russian émigré couple, bearing the poignant gift of ten little jars of fruit jellies, visits their “incurably deranged” son in a sanitarium. After enduring rain, subway delays, bus delays, and a spell in the hospital’s waiting room (“That Friday everything went wrong,” the narrator warns), they are met by a nurse who tells them that their son has attempted suicide, again, and any visitors would be an unwelcome disturbance.

Their son, it transpires, has “referential mania”: “In these very rare cases, the patient imagines that everything happening around him is a veiled reference to his personality and existence…. Phenomenal nature shadows him wherever he goes.” The objects and phenomena of the world—wallpaper or thunderstorms, pebbles or coats in store windows—he perceives to be ripe with meaning, “hives of evil, vibrant with a malignant activity.” The result: “He must be always on his guard and devote every minute and module of life to the decoding of the undulation of things.” It is a kind of psychosis, but it is also, Nabokov suggests, not insane—not exactly. Some things do need decoding; some things mean things. Or rather, sometimes we wish them to mean something, and sometimes we must be told when to stop.

Lately it has been easy to indulge in a kind of referential mania. Last week saw an earthquake in New York City, Mount Etna blowing smoke rings, a comet—the Devil Comet, no less—and, the crowning event, a total solar eclipse. These are not simply wallpaper and coats. But nor have the waters of the earth turned to blood. There have been at least eight earthquakes in the New York area since 1927. Total solar eclipses have passed over the United States seventeen times since 1918; three more will follow before 2045. Still, for anyone with a little romance in his heart and a reluctance to travel to Nome, Alaska, on March 30, 2033, the desire to look a celestial omen in the face and decode the undulation of things was strong.

There are apparently many such people. April in Vermont is mud season, a far cry from fall foliage and winter skiing, but the train from New York City to St. Albans, to the path of totality, was sold out. The conductors in the dining car, where my boyfriend and I had set up for want of seats in coach, marveled that the route is often canceled this time of year due to insufficient sales. On the few highways in Vermont, signs lined the road warning of the coming crowds and instructing drivers only to pull over in case of emergency.

There were reports that motels in Vermont had kicked out long-term residents to accommodate some of the estimated 160,000 visitors, but we were staying with my stepsister, who met us at the train station in Randolph and drove us first to her mom’s house for dinner. We ate barbecue ribs and piled the bones in a dark blue bowl.

My stepsister lives in an A-frame off a winding dirt road, on a ridge in the woods. Earlier that week a freak snowstorm had dumped a foot and a half of snow on the area and knocked her power out until the day before; the road leading up to her house was rutted and soggy. Throughout this unseasonably warm winter, Vermont had been hit by blizzards that were followed by rain, reportedly making the state’s famous network of unpaved roads marshier than usual, earlier than usual.

We drove to a new pool hall in Barre, the “Granite City,” which last summer faced catastrophic floods that washed out roads, destroyed dozens of homes and businesses, and killed a man. Now posters bearing the slogan “Barre Strong” were up in some downtown windows, next to the Largest Zipper in America, a seventy-four-foot granite sculpture that in the spring and summer encloses a garden that in early April was still unplanted. The pool hall closed early, just as we arrived. The bartender said business was too slow. In Burlington, forty-five miles away, another obscure omen: two days earlier, a would-be arsonist had tried to burn down Bernie Sanders’s office.

*

After their aborted visit to see their son at the sanitarium, the old couple in “Signs and Symbols” make their way home, trailed everywhere by portents. “What he had really wanted to do,” the narrator says of one of the boy’s suicide attempts, “was to tear a hole in his world and escape.”

We were watching the eclipse at the home of my stepsister’s friend, near Sugarbush Mountain, at the southern edge of the path of totality. Her house is set into the side of a small hill in a sprawling clearing in the woods. At the door, we were greeted by her six-year-old son. “The dogs ran away,” he reported matter-of-factly. The sun was bright and we had an hour to kill, so my boyfriend and I walked into town, trudging in the muddy berm alongside Brook Road, past a row of great boulders and a few clapboard houses. On Main Street we encountered what for a small town would count as a traffic jam: a dozen cars parked at the general store, people milling around speculating about the eclipse. “Maybe at 3:28 we find out we’re related, or some kind of profound thing happens,” one man said to his friend.

We stepped into an art gallery on the Mad River. In celebration of the eclipse the proprietress was wearing a puffy gold lamé jacket and parachute pants, as well as gold lipstick and eye shadow. “Just don’t ask me to move!” she said by way of greeting, before eagerly walking us around the rooms and upstairs to her studio, enthusing about the local artists whose work adorned the walls and hung from the ceiling. There was a series of striking geometric, color-blocked barns, some bluish abstracts, flattened thickets of trees and overgrowth, and several monumental mounted animal heads—a bear, a coyote—made from felt. “Aren’t they great?” she said. “Much better than slaughtering them.”

Back at the house they had set up a row of folding chairs in the melting snow. The children were theatrically unenthusiastic. “I already saw it!” “I want to go on my bike!” Maybe feeling some responsibility to the semiregular alignment of the spheres, as if the cosmic order would collapse if we failed to witness it, is a lunacy peculiar to adults, who spend our days fending off entropy and chaos. The kids, for their part, seemed to take for granted that everything was happening as it was supposed to. Why shouldn’t the moon pass precisely in front of the sun?

We wiser grown-ups, meanwhile, were staring at the sun. Not directly, although my boyfriend told me about a high school acquaintance who did adopt the practice of sun-staring because he believed that he could receive most necessary forms of sustenance from its rays, like a plant. Did he damage his eyes? I asked. Yes.

We were on firmer ground reiterating to the children that this was a rare event. The harder part was articulating why it was magical. As the moon crept farther across the face of the sun, they kept complaining and rolling their eyes, and we rehearsed all the usual metaphors about its significance and beauty: celestial dance, fingernail, eyelash, a filament dying out. At this last, as the darkening sky became undeniably eerie and the land stilled, the children finally seemed to understand. The birds got quiet, save one, wailing far off in the trees. In the moments before totality, bands of shadow rippled across the snow.

“It’s like the end of school,” said the six-year-old.

“It’s like the end of the world,” said his older sister.

Then, at last, silence.

There: a thin, silver band of undulating, liquid light, plugged by the moon, straining to get out.

Then it did. The darkness ebbed, the kids scattered across the lawn, and I retreated into our hosts’ basement, where it was quiet and the Wi-Fi was strong enough for me to join a video conference. No one, as my stepmom later said, was sucked off the earth. When I finished work, I found, back upstairs, that the dogs had safely returned. One was covered in mud, and the other had brought back half of a mandible, with six sharp molars in it, a little red with blood. 🌓

Big Time Sensuality

Lucy Jakub in the Rangeley Lakes, Maine

When my mother learned that her three daughters were making plans to see the solar eclipse together, she couldn’t resist throwing shade: “I just don’t get the point of an eclipse.” Even totality, she thought, was likely “overrated.”

What is the point of an eclipse? The moon passes directly between the sun and the Earth two to five times a year. The last time it did so over North America was in August 2017, casting its shadow from Oregon to South Carolina. I saw it from the Bronx through a pinhole in a moving box. The camera obscura, the original instrument of study for solar eclipses, held greater fascination than the partial eclipse, which appeared in the box about the size of a chad.

That was Saros 145. The eclipse that traveled from Mexico to Maine on April 8 was part of Saros 139 and will be the last solar eclipse visible in the contiguous United States for twenty years, which was reason enough to try to see it. Eclipses occur in cycles, as the moon crisscrosses the tilting globe the way yarn is wrapped around a ball, and the cycles make patterns. Every eighteen years, eleven days, and eight hours—one saros—Earth, moon, and sun align in the same way, with the new moon at the same distance from the Earth, and the Earth tilted the same angle from the sun; but that third of a day means that this convergence recurs over different parts of the globe, returning to the same region every third saros.

The Greeks called this interval the exeligmos, a turning of the wheel, their earliest cosmology holding that the sun and the moon were great wheels of fire emitting their light at certain apertures. In 1970, at the last local exeligmos of Saros 139, which skimmed the Atlantic seaboard from Tallahassee to Halifax, my mother was eight and would have been treated to a partial eclipse of 0.95 magnitude in Newburyport, Massachusetts. She doesn’t remember whether she saw it.

*

A week before the eclipse, Joe comes to stay with us. My roommate, Owen, hasn’t seen Joe since their freshman year at college. He’s in New York to tour the Brooklyn Zen Center, where he’s applied to a residency—although his first impression of the city is that it is loud, dirty, and has too many people. Maybe that’s just what he needs to train in tranquility.

Joe saw Saros 145 in an orchard in Oregon, where he’s lived his whole life. When I suggest to him that the point of an eclipse might depend on how much significance one gives to the phenomenon of coincidence in general, Joe finally shows some emotion. I’ve got it backwards. How could the awe of totality be compared with anything as trivial as numbers lining up on your odometer?

“Didn’t Annie Dillard write an essay about a total eclipse?” says Owen.

What I really have in mind is the convergence of people and events, that you can be in the right place at the right time for the right thing to happen. For example, six months ago, as I was walking to a birthday party in Crown Heights, a cat in crisis came up to me on the street. I’d never been approached by a stray before. I didn’t have a cat, because I couldn’t be tied down, making the New York–Los Angeles transit every few months to see my long-distance partner. But I decided if the cat was still there when I returned that way, I would take her home with me.

Joe responds with a Zen aphorism. “Not knowing is most intimate.”

As early as 100 BC, the Greeks were able to calculate the exeligmos with an intricate piece of bronze clockwork, the oldest known analog computer. But the Greeks also thought the sun was like a chariot wheel.

My sisters, Abigail and Susanna, live in Portland, about eighty-five miles south of the path of totality, which will darken much of Maine’s second congressional district. I live in Brooklyn. As I’m getting ready to leave my apartment on Friday, it begins to shake. What I assume are the usual J train tremors amplify and continue for half a minute—a jolt I thought I’d left behind in Los Angeles. My cat and I cling to the floor and stare at each other.

Sam picks me up at noon on East Houston in a gold 2001 Toyota Sienna. His mechanic has warned him that the undercarriage is so rusted a speed bump could knock the engine out. He is driving to Boston to rendezvous with an old friend, who is at Harvard for the annual Goethe workshop. I am lucky to get a lift because all but three of the minivan’s seats have been removed. We pick up Matthew in Hudson Yards and drive up the blooming greenway, with the windows down because the heat won’t turn off.

Matthew saw Saros 145 in Kentucky. It wasn’t the eclipse itself that felt particularly meaningful, but the fact that for perhaps the first time ever his suburban family had piled into a car and gone on a drive to look at nature together. What is the purpose of pilgrimage? These two boys, who have announced intentions to live in New York until they die, keep laughing at the pilgrim hat on signs for the Mass Pike. I’ve done this route countless times.

We amble around the campus where my parents met forty years ago. It’s wet and gray, and wild turkeys are preening among the tourists. It was a summer acting and directing workshop. She had just dropped out of acting school; he needed one more credit to graduate with a concentration in film. The last time I was in Cambridge was exactly four years ago, after the pandemic began and just before I moved to Los Angeles. When I left it felt like the world would never be the same, but being back now, it feels utterly familiar.

I take the T to Jamaica Plain, where I’m staying the night with Owen’s older sister. Tess is deciding between two graphic design programs, in Pittsburgh and Seattle, and I want her to choose the farther shore. She’s lived in Boston for practically her whole life. “Maybe I will never come back,” she says, both thrilled and apprehensive at the prospect. “You have to leave in order to come back,” I tell her.

Why doesn’t she come with us? She can get a ride with Owen, who will take the train to Boston and on Sunday drive to Portland in the family car. But Tess is reluctant to miss a day of work. Anyway, she’s already seen one. She pulls up photos on her phone from Saros 145. Her cousins are on a North Carolina beach in swimsuits, paper glasses, silly hats, and full sun. “You weren’t in the shadow,” I point out. “It wasn’t total.”

Was her mother living in Newburyport yet, in 1970? Tess doesn’t know.

On Saturday morning she drives me to South Station in her little car that’s littered with old coffee cups and antiques she bought years ago. In the Concord Coach boarding line a retiree from Maine is hitting it off with a woman from Virginia. “This seat taken?” he asks. “All yours!” she says. Abigail picks me up in Portland, and I sleep on her couch while she makes chocolate cookies for the eclipse.

On Sunday morning we walk to Reny’s to buy a map, because we’re likely to lose service on the road if thousands of visitors strain the networks. Reny’s: A Maine Adventure! doesn’t sell maps. We stop at the coffee shop where Susanna is training as a barista. Her boyfriend, Carter, is there, and we discuss our route. We all grew up on the Maine coast, but the expanse north of Lewiston is the dark side of the moon: it hosted no track meets, its antiques did not beckon on Craigslist. Abigail has been doing the research. The further north we go, the longer totality will last. We need an elevated and unobstructed view in order to see the passage of the moonshadow. There will be deep snow, so we won’t be able to hike. Carter has heard that all the state parks are closed.

They’re playing Björk in the vintage boutique where I finally find the black Old Navy nylon shift I’ve been looking for. “It takes courage/to enjoy it/the hardcore and the gentle.” In the used bookstore below Abigail’s apartment I buy The Copernican Revolution. Before the heliocentric model was proposed, Thomas Kuhn writes, theories of the shape of the universe were only loosely related to observable features of nature, their purpose being to “fulfill a basic psychological need”:

they provide a stage for man’s daily activities and the activities of his gods…. Man does not exist for long without inventing a cosmology, because a cosmology can provide him with a worldview which permeates and gives meaning to his every action, practical and spiritual.

I walk to meet my old high school friend Nolan and his little dog on the Western Promenade, a park with an incredible view of the Portland International Jetport. Nolan points out the building where he works, the children’s museum. “The gray box with the blue box on the roof.”

I ask him how he feels about getting married in October. He turns to me with a huge smile on his face: “It took me a while to get excited about the wedding—but nesting, building a family, life!” He makes a sweeping gesture at the dun grass hillside. “I’m so excited for that!”

He returns the question, unexpectedly. I tell him I’ve recently learned that you can love someone more than almost anything; you can be mysteriously bonded, maybe forever; and it doesn’t mean that you can or should join your life to theirs, have children with them, or grow old together.

Why isn’t he driving to totality? He’s so close, and he even requested the afternoon off. But instead he is going to sit with his coworkers in the blue box on the roof, which is a camera obscura. “I mean, I remember reading Annie Dillard in college, and that something about the experience was transformative for her,” he says. “But I don’t quite remember what.”

I tell him what she says is that the difference between seeing a partial eclipse and a total one is the difference between kissing a man and marrying him. His face falls a bit. “Oh.”

*

On the eve of the eclipse, Owen arrives from Boston. We leave the apartment at seven on Monday morning to pick up Susanna and Carter. There isn’t a cloud in the sky as we head north on I-95. My parents text the family group chat. They are driving to Burlington after all.

We reach Auburn as the school bus is making its rounds. Peeling paint, boarded up windows, disintegrating barns. Denny’s. Frost-covered fields. Turner, and we’re in the path of totality. This whole landscape of pointed hills is sodden with standing snowmelt and overflowed streams. Against the faded brown houses and bare trees, fresh signs scream: TURN ON HEADLIGHTS FOR YOUR SAFETY. DRIVE WITH CAUTION. FUCK BIDEN. Rumford. The rusted tracks lead to the railyard, and the Androscoggin River leads to the paper mill, which stinks like sulfur. Mexico. Frosty Delite. Pawn & Gun. Antiques and apple trees. UNITED WE STAND, DIVIDED WE FALL. The opinion pages suggest that an eclipse will “unite our divided nation,” but Susanna doesn’t think we’re safe here driving a new hybrid with Mass plates.

Goethe: “If the whole of existence is an endless dividing and uniting, it follows that humans, in their beholding of this uncanny condition, will also sometimes divide, sometimes unite.”

With some elevation gain, the air clears and the colors change. We’re in the Rangeley Lakes, where the snowpack is pristine and shines on the pines and birches. The lakes are still frozen over, spread white between the mountains, and the deep valleys are shadowed in cobalt. Owen remarks that he hasn’t been somewhere this beautiful in a long time. We lose service, and consult the legal pad with our itinerary in Sharpie. Plan A: Height of Land, perhaps the most spectacular vista in the state, 2,250 feet over Mooselookmeguntic Lake, facing the White Mountains. The narrow shoulder is already jammed full of cars. We continue on to Vista Point. Also full. People in ponchos walk along the side of the road.

Plan C: Shelton Noyes Overlook. This is the one. We park on the shoulder and I run into the forest to pee, sinking into three feet of powder. The roundabout is already full of campers and a colony of tripods has been erected on the central island, but there is plenty of space to sit and look north over Rangeley Lake at the encircling purple hills. We shove our camp chairs into the snow behind a stand of red twig dogwood and an informational plaque about the timber industry. For the next four hours we read our books, eat our ham sandwiches, and admire the lake. A kid is churning a bubble machine for all he’s worth. Local news is here. Some jerk brought a drone. Abigail does a crossword puzzle. I pull my hat over my face to block the glare and try to doze off.

At 2:18 people start putting on their paper glasses. We check the sun, which is over the campers and the tree line. There’s the unmistakable divot. The first part of the transit will take over an hour, and totality in our location will last only two and a half minutes. Carter sets up his Nikon. Susanna sets out her crystals to charge. A high school science teacher is telling the group next to us, “I’ve read an author in her memoir saying that the shadow comes at you very quickly.”

A turkey vulture circles the lake and wheels away toward Saddleback. Susanna is casting her eyes anxiously over the snow, saying she may have burned a crescent-shaped scar into her retina. Owen seems content to sit and watch the entire transit, but I have to pee again. The tailgate now snakes around the bend in the road. New York plates, Washington plates, Connecticut plates, Virginia plates, Colorado plates. No time to find the end of it. The lunatics have set up telescopes next to their cars; they’re wearing souvenir T-shirts, they’ve brought out specially decorated cakes, they’re blasting the Goo Goo Dolls. Somebody yells to me, “Put your glasses on, kid! It’s already started!”

Back at the overlook the stage lights are coming down. Everything that was bright is faded. The wind has picked up and my fingers are numb. I hold the glasses so I can keep an eye on the shrinking orange sliver, but my attention is on the northwest, where the sky over the mountains is turning rosy. I can sense it. Something important is about to happen.

It’s coming now. 🌒